Understanding Alloy Design Principles and Cast Metal Technology in Hot Molds for Medieval Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENLISTED Ngos of the STATE BOARD for 2009-10

ENLISTED NGOs OF THE STATE BOARD FOR 2011-12 SL. NAME DATE OF REGISTRATION ADDRESS PHONE/E-Mail CONTACT PERSON ACTIVITY DISTRICT NO. ENLISTMENT NO. REPORT 1. BADULARA DISHARI 04.04.2011 S/1L/25542 of P.O. West Sanabandh, 03242-243026, 94343 Shri Mohinoor Alam, Submitted Bankura SOCIETY 2004-2005 Dist. Bankura-722 181 92874 Secretary dishari_bankura@redif fmail.com 2. CHANPASHOLE RURAL Before 2011 S/1L/41716 of Vill : Chanpashole, P.O. 9475865710/94345465 Shri Ranjit Mondal, Submitted Bankura DEVELOPMENT SOCIETY 2006-2007 Jhantipahari, 73 Secretary Dist. Bankura, Pin ± [email protected] 722137 3. GHUTGORIA AGRAGAMI 04.04.2011 S/1L/72565 of Vill+P.O : Ghutgoria , 94774 01805 Shri Anup Karmakar, Submitted Bankura 2010-2011 P.S. Barjora [email protected] Secretary Dist Bankura, Pin-722168 4. KELIAPATHAR SABUJ Before 2011 S/29694 of 1980- Vill. & PO. Keliapathar, 03242-260055 Shri Bhutnath Layek, Submitted Bankura SANGHA & LIBRARY 1981 PS. Indpur, Dist. Bankura, [email protected] Gen. Secretary Pin. 722136. 5. KHAYERBONI GRAM 04.04.2011 S/54572 1986- Vill-Khayerboni, P.O. 94744 59013 Shri Aditya Kumar Submitted Bankura UNNAYAN SAMITY 1987 Kanchanpur, kgus_bankura@rediffmGhosh, Secretary Dist. Bankura ± 722155 ail.com (W.B) 6. MY DEAR TREES & Before 2011 S/72076 of 1992- Dhulapara, Mukutganj, (03244) 255549 Shri Goutam Submitted Bankura WILDS 93 (Behind Manisha), Gangopadhyay, Bishnupur, Dist. Bankura, Secretary Pin. 722 122 7. SOOKJORA PALLI Before 2011 S/21131 of 1977- Vill: Sookjora, P.O.- 03244/250633, Shri Sanat Kumar Submitted Bankura GATHAN SAMITY 1978 Gelia, 23379473 Sarkar, Dist-Bankura, Secretary Pin-722154 8. BENEVOLENT 04.04.2011 S/1L/24453 of Sonatorepara, P.O. -

UAW Ford Agreements Cvr 1Up.Indd 2 11/15/16 7:07 AM SKILLED TRADES AGREEMENTS and LETTERS of UNDERSTANDING

SKILLED TRADES AGREEMENTS AND LETTERS OF UNDERSTANDING between UAW® and the FORD MOTOR COMPANY Agreements Dated November 5, 2015 133 MICHIGAN (Effective November 23, 2015) ♲ printed on recycled paper PRINTED IN U.S.A. 64353-UAW Ford Skilled Trades Cvr 1up.indd 1 10/26/16 8:24 AM National Ford Department Staff 2015 Negotiations Jimmy Settles Vice President and Director UAW Ford, Aerospace, Chaplaincy and Insurance Greg Drudi Roy Escandon Angelique Peterson- Don Godfrey Jeffrey Faber Mayberry Brett Fox Ford Motor Company and the UAW recognize Darryl Nolen Gregory Poet Kenneth Gafa their respective responsibilities under federal Bob Tiseo Reggie Ransom and state laws relating to fair employment Phil Argento Michael Gammella Lorenzo Robinson practices. Tracy Ausen Raenell Glenn Michael Robison Carol Bagdady R. Brian Goff Nick Rutovic The Company and the Union recognize the Matthew Barnett Ruth Golden Angelo Sacino Monica Bass moral principles involved in the area of civil Jane Granger Les Shaw David Berry rights and have reaffirmed in their Collective Andre Green Michael Shoemaker Carlo Bishop Bargaining Agreement their commitment not Joe Gucciardo Casandra Shortridge Shawn Campbell to discriminate because of race, religion, color, Dan Huddleston Larry Shrader Jerry Carson age, sex, sexual orientation, union activity, Michael Joseph Garry Sommerville Alfonzo Cash Thomas Kanitz national origin, or against any employee with Jeffrey Terry Tiffany Coger Brandon Keatts disabilities. Kevin Tolbert Gerard Coiffard Michael Kerr Vaughan Tolliver Sean -

United Bank of India - Latest CSP List

United Bank of India - Latest CSP List S.No. Village Name Base Branch District State BCA Name Contact No. Joining Date 1 GOPALPUR Bedaul Asli Muzaffarpur Bihar Abhay Kumar 9955962362 09.09.2011 2 BHARAT PATTI Bedaul Asli Muzaffarpur Bihar Nityanand Singh 9162065475 09.09.2011 3 THENGPUR Bahdinpur Muzaffarpur Bihar Vinay Kumar Sah 9939515448 09.09.2011 9199645686 4 TILAKPAKRI Basantpur patti Muzaffarpur Bihar Mukesh Kumar Thakur 9471819911 09.09.2011 8252459101 5 BANAULI Basantpur patti Muzaffarpur Bihar Chandrashekhar Sharma 9939876972 09.09.2011 6 BAHLOLPUR Bahdinpur Muzaffarpur Bihar Chandeshwar Ram 9572019378 09.09.2011 7 INDAULIA Bahdinpur Muzaffarpur Bihar Ravi Kumar 9955234908 09.09.2011 8 FIROZPUR Bahdinpur Muzaffarpur Bihar Dinesh Kumar 9934946160 09.09.2011 9 AYODHAPUR Basantpur patti Muzaffarpur Bihar Sabita Kumari 8809915794 09.09.2011 10 JAGDISHPUR Purshottampur Muzaffarpur Bihar Lalan kumar 9798660862 01.12.2011 11 BAHBAL BAZAR Minapur Muzaffarpur Bihar Abdhesh Kumar 8603374370 01.12.2011 12 DAUDPUR Gokula Muzaffarpur Bihar Md.Naushad alam 9939007864 01.12.2011 13 USTI Gokula Muzaffarpur Bihar Md.Amin Kaushar 8809175008 01.12.2011 14 BHAGWATPUR Gokula Muzaffarpur Bihar Satyandra kumar singh 9006499435 01.12.2011 15 BISUNPURKANTH Minapur Muzaffarpur Bihar Ram babu ray 9939177312 01.12.2011 16 DARHIPATTI Minapur Muzaffarpur Bihar Chandan kumar 9939264291 01.12.2011 17 KHEMAIPATTI Minapur Muzaffarpur Bihar Manish kumar 9631163935 01.12.2011 18 MANIKPUR Minapur Muzaffarpur Bihar Islam Ansari 9534508370 01.12.2011 19 PHULWARIA -

The Return of Coppersmith's Attack:Practical Factorization of Widely Used RSA Moduli

Session H1: Crypto Attacks CCS’17, October 30-November 3, 2017, Dallas, TX, USA The Return of Coppersmith’s Aack: Practical Factorization of Widely Used RSA Moduli Matus Nemec Marek Sys∗ Petr Svenda Masaryk University, Masaryk University Masaryk University Ca’ Foscari University of Venice [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Dusan Klinec Vashek Matyas EnigmaBridge, Masaryk University Masaryk University [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION We report on our discovery of an algorithmic aw in the construc- RSA [69] is a widespread algorithm for asymmetric cryptography tion of primes for RSA key generation in a widely-used library used for digital signatures and message encryption. RSA security of a major manufacturer of cryptographic hardware. e primes is based on the integer factorization problem, which is believed generated by the library suer from a signicant loss of entropy. to be computationally infeasible or at least extremely dicult for We propose a practical factorization method for various key lengths suciently large security parameters – the size of the private primes including 1024 and 2048 bits. Our method requires no additional and the resulting public modulus N . As of 2017, the most common information except for the value of the public modulus and does length of the modulus N is 2048 bits, with shorter key lengths not depend on a weak or a faulty random number generator. We such as 1024 bits still used in practice (although not recommend devised an extension of Coppersmith’s factorization aack utilizing anymore) and longer lengths like 4096 bits becoming increasingly an alternative form of the primes in question. -

Journal of Milk Technology

'-/· .> Ί ' JOURNAL OF MILK TECHNOLOGY Volu 14 Number 2 MARCH-APRIL, 1941 Official Publication of International Association of Milk Sanitarians (Association Organized 1911) Alto designated publication of California Association of Dairy and Milk Inspectors Central States Milk Sanitarians Chicago Dairy Technology Society Connecticut Association of Dairy and Milk Inspectors Indianapolis Dairy Technology Club Massachusetts Milk Inspectors’ Association Metropolitan Dairy Technology Society Michigan Association of Dairy and Milk Inspectors Missouri Association of Milk Sanitarians New York State Association of Dairy and Milk Inspectors Pacific Northwest Association of Dairy and Milk Inspectors Pennsylvania Association of Dairy Sanitarians Philadelphia Dairy Technology Society Texas Association of Milk Sanitarians West Virginia Association of Milk Sanitarians II A dvertisements PERHAPS as a boy you took many a drink from it without a thought about how insanitary it might be. N ot so today. The patient work of sanitation and pub YOUR DAIRY CUSTOMERS can actually lic health officers has taught you to say see the safe protection of the Welded “nix” to the public drinking cup. And Wire Hood —and seeing is believing. their science, too, has solved many They recognize that you are safeguard problems of dairy sanitation—including ing their health when they see how you how to protect the pouring lip of your protect that pouring lip from contami sterilized milk and cream bottles. nation. Vet, even though the Hood is locked on with welded wire, it comes off HEALTH OFFICERS themselves say that quickly, without effort. they prefer the complete protection of the Welded Wire Hood Seal. It covers FREE INFORMATION-W rite for details the entire pouring lip and top against on Hood Capping and our interesting insanitary dust and filth. -

The Industrial Role of Scrap Copper at Jamestown Carter C

THE JOURNAL OF THE JAMESTOWN Carter C. Hudgins REDISCOVERY CENTER “Old World Industries and New World Hope: The VOL. 2 JAN. 2004 Industrial Role of Scrap Copper at Jamestown” Available from https://www.historicjamestowne.org Old World Industries and New World Hope: The Industrial Role of Scrap Copper at Jamestown Carter C. Hudgins 1. Introduction Jamestown scholars have long believed that during the first ten years of the Virginia Colony (1607-1617), settlers attempted to elude starvation by trading European copper with local Powhatans in exchange for foodstuffs. Contem- porary reports, such as those written by John Smith, docu- Figure 1. A sample of scrap waste selected from copper found at ment this bartering, and recent archaeological discoveries Jamestown. of over 7,000 pieces of scrap sheet copper within James Fort seem to substantiate the existence of this commerce (Figure 2. Jamestown’s Scrap Copper 1). Although much of this waste metal was undoubtedly Examinations of the scrap copper found in Jamestown associated with the exchange of goods between the English Rediscovery’s five largest Fort-Period features—Pit 1, Pit 3, and Powhatans, this study suggests that significant amounts Structure 165, SE Bulwark Trench, and Feature JR 731— of Jamestown’s scrap copper were also related to contempo- reveal that a significant percentage of the copper bears manu- rary English copper industries and an anticipation of met- facturing evidence that can be credited to coppersmithing allurgical resources in the New World. industries in England. Several examples of copper that pos- th During the late 16 century, the Society of Mines Royal sess the markings of English industry are shown in Figures and the Society of Minerals and Battery Works were formed 2, 3 and 4, and relate to the making of copper wire, buckles to mine English metals, produce copper-alloy products, and and kettles respectively. -

Coppersmith Media

Contact: Todd Messelt Media Line Communications 612.222.8585 [email protected] Twin Cities-based CopperSmith® emerges as leading e-retailer of upscale home products, including in-house brand of handmade, custom-order, solid copper range hoods, sinks, bathtubs and more Specialty manufacturer and e-retailer of high-end housewares credits steady growth to a direct-to-consumer business model, offering live product support, free design assistance, and drop-shipping services to homeowners, interior designers and home builders. GOLDEN VALLEY, MINN.—In 2009, Ryan Grambart dove head-first into launching CopperSmith® ( www. worldcoppersmith.com ), galvanized by the allure of a semi-precious metal that has attracted artists, designers and architects for more than 10,000 years. Since its humble beginnings as a purveyor of copper gutter systems for Twin Cities-area homes, Grambart’s fledging company has emerged as a leading Online retailer and specialty in-house manufacturer of upscale, premium-quality products for discerning homeowners; while offering wholesale B2B programs and drop-shipping services to contractors and interior designers seeking made-to-order range hoods, kitchen sinks, farmhouse sinks, bathroom sinks, tables, light fixtures, mirrors, towel bars and rings, cabinet knobs and pulls, flooring tiles and registers, cookware and more. “We got our start manufacturing, installing and retailing a small line of specialty products we believed in,” says Grambart. “We’re not just another e-commerce company posting a zillion skus hoping for some quick and easy sales. We have a thriving installation business that serves local building contractors and provides front-line market research and hands-on working knowledge of the products we sell nationally.” Direct-to-Consumer Approach CopperSmith® was founded on the principle that our quality of life is profoundly affected by the products we surround ourselves with. -

U.S. Navy Enlisted Ratings

U.S. Navy Enlisted Ratings Designation Title ABCM Master Chief Aviation Boatswain's Mate (E-9 only) ABE Aviation Boatswain's Mate Launch & Recovery Equipment ABF Aviation Boatswain's Mate Fuels ABH Aviation Boatswain's Mate Aircraft Handling ABM Aviation Boatswain's Mate (1944-1948) ABU Aviation Boatswain's Mate Utility AC Air Controlman (1948-1977) AC Air Traffic Controller (1977- ) ACM Aviation Carpenter's Mate (1921-1940) (to AM) ACT Aircontrolman Tower ACW Aircontrolman Early Warning AD Aviation Machinist's Mate (1948- ) ADE Aviation Machinist's Mate Engine Mechanic ADF Aviation Machinist's Mate Flight Engineer ADG Aviation Machinist's Mate Carburetor Mechanic ADJ Aviation Machinist's Mate Jet Engine Mechanic ADP Aviation Machinist's Mate Propeller Mechanic ADR Aviation Machinist's Mate Reciprocating Engine Mechanic AE Aviation Electrician's Mate (1948- ) AEM Aviation Electrician's Mate (1942-1948) AETM Aviation Electronic Technician's Mate (1945-1948) AF Photographer's Mate (1948-1950) (to PH) AFCM Master Chief Aircraft Maintenanceman (E-9 only) (1963- ) Aerog Aerographer (1923-1942) AerM Aerographer's Mate (1942-1948) AG Aerographer's Mate (1948- ) AK Aviation Storekeeper (1948-2003) (to SK) AL Aviation Electronicsman (1948-1959) (to AT) AM Aviation Metalsmith (1921-1948) AM Aviation Structural Mechanic (E-8 only) AME Aviation Structural Mechanic Safety Equipment AMH Aviation Structural Mechanic Hydraulic Mechanic (1948-2001)(to AM) AMM Aviation Machinist's Mate (1921-1948) (to AD) AMMC Aviation Machinist's Mate Carburetor Mechanic AMMF Aviation Machinist's Mate Flight Engineer AMMH Aviation Machinist's Mate Hydraulic Mechanic AMMI Aviation Machinist's Mate Instrument Mechanic AMMP Aviation Machinist's Mate Propeller Mechanic AMMT Aviation Machinist's Mate Gas Turbine Mechanic AMS Aviation Structural Mechanic Structures (1948-2001)(to AM) AO Aviation Ordnanceman (1948- ) AOMB Aviation Bombsight Mechanic (1943-1944) U.S. -

Commodity Master List

Commodity Master List 005 ABRASIVES 010 ACOUSTICAL TILE, INSULATING MATERIALS, AND SUPPLIES 015 ADDRESSING, COPYING, MIMEOGRAPH, AND SPIRIT DUPLICATING MACHINE SUPPLIES: CHEMICALS, INKS, PAPER, ETC. 019 AGRICULTURAL CROPS AND GRAINS INCLUDING FRUITS, MELONS, NUTS, AND VEGETABLES 020 AGRICULTURAL EQUIPMENT, IMPLEMENTS, AND ACCESSORIES (SEE CLASS 022 FOR PARTS) 022 AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENT AND ACCESSORY PARTS 025 AIR COMPRESSORS AND ACCESSORIES 031 AIR CONDITIONING, HEATING, AND VENTILATING: EQUIPMENT, PARTS AND ACCESSORIES (SEE RELATED ITEMS IN CLASS 740) 035 AIRCRAFT AND AIRPORT, EQUIPMENT, PARTS, AND SUPPLIES 037 AMUSEMENT, DECORATIONS, ENTERTAINMENT, TOYS, ETC. 040 ANIMALS, BIRDS, MARINE LIFE, AND POULTRY, INCLUDING ACCESSORY ITEMS (LIVE) 045 APPLIANCES AND EQUIPMENT, HOUSEHOLD TYPE 050 ART EQUIPMENT AND SUPPLIES 052 ART OBJECTS 055 AUTOMOTIVE ACCESSORIES FOR AUTOMOBILES, BUSES, TRUCKS, ETC. 060 AUTOMOTIVE MAINTENANCE ITEMS AND REPAIR/REPLACEMENT PARTS 065 AUTOMOTIVE BODIES, ACCESSORIES, AND PARTS 070 AUTOMOTIVE VEHICLES AND RELATED TRANSPORTATION EQUIPMENT 075 AUTOMOTIVE SHOP EQUIPMENT AND SUPPLIES 080 BADGES, EMBLEMS, NAME TAGS AND PLATES, JEWELRY, ETC. 085 BAGS, BAGGING, TIES, AND EROSION CONTROL EQUIPMENT 090 BAKERY EQUIPMENT, COMMERCIAL 095 BARBER AND BEAUTY SHOP EQUIPMENT AND SUPPLIES 100 BARRELS, DRUMS, KEGS, AND CONTAINERS 105 BEARINGS (EXCEPT WHEEL BEARINGS AND SEALS -SEE CLASS 060) 110 BELTS AND BELTING: AUTOMOTIVE AND INDUSTRIAL 115 BIOCHEMICALS, RESEARCH 120 BOATS, MOTORS, AND MARINE AND WILDLIFE SUPPLIES 125 BOOKBINDING SUPPLIES -

ACTION: Filed DATE: 06/16/2008 11:33 AM ENACTED

ACTION: Filed ENACTED DATE: 06/16/2008 11:33 AM Appendix Rev. July 2008 4123-17-04144 Insurance Fund Manual NATIONAL COUNCIL ON COMPENSATION INSURANCE (NCCI) CLASSIFICATION OF INDUSTRIES Alphabetical index begins on page 145. This index is furnished as a quick look up tool for locating specific classifica- tion numbers. Subsequent referencing of the numerical index is suggested to ensure proper classification. Numerical index begins on page 203. This information is associated with 4123-17-04. © Classifications reprinted with permission of the National Council on Compensation Insurance, all rights reserved. APPENDIX p(37142) pa(52177) d(186912) ra(156431) print date: 06/16/2008 9:01 PM Rev. July 2008 145 Insurance Fund Manual NATIONAL COUNCIL ON COMPENSATION INSURANCE (NCCI) ALPHABETICAL INDEX CLASSIFICATION OF INDUSTRIES A Abrasive wheel manufacturing and drivers......................................................................................................... 1748 Absorbent cotton manufacturing......................................................................................................................... 4693 Accountant, auditor or factory cost or office systematizer-traveling ................................................................... 8803 Acetate textile fiber ............................................................................................................................................. 2305 Acetylene gas machine installation and drivers................................................................................................. -

Cuivres, Bronzes Et Laitons Médiévaux / Medieval Copper, Bronze and Brass

CUIVRES, BRONZES ET LAITONS MÉDIÉVAUX / MEDIEVAL COPPER, BRONZE AND BRASS Histoire, archéologie et archéométrie des productions en laiton, bronze et autres alliages à base de cuivre dans l’Europe médiévale (12e-16e siècles) History, archaeology and archaeometry of the production of brass, bronze and other copper alloy objects in medieval Europe (12th-16th centuries) Sous la direction de Nicolas Thomas & Pete Dandridge Tiré à part / Off-print Gardner C., Martinón-Torres M., Topić N., Peković Ž., 2018, « Analysis of archaeometallurgical finds from a late to postmedieval foundry in Dubrovnik, Croatia », in Thomas N., Dandridge P. (éd.), Cuivre, bronzes et laitons médiévaux : Histoire, archéologie et archéométrie des productions en laiton, bronze et autres alliages à base de cuivre dans l’Europe médiévale (12e-16e siècles). Medieval copper, bronze and brass: History, archaeology and archaeometry of the production of brass, bronze and other copper alloy objects in medieval Europe (12th-16th centuries), [Actes du colloque de Dinant et Namur, 15- 17 mai 2014. Proceedings of the symposium of Dinant and Namur, 15-17 May 2014], Namur, Agence wallonne du Patrimoine, p. 309-325. (Études et documents, Archéologie ; 39). Études et Documents Archéologie Agence wallonne du Patrimoine 39 Études et Documents Archéologie 39 La série ARCHÉOLOGIE de la collection ÉTUDES ET DOCUMENTS est une publication de l'AWaP Service public de Wallonie Direction générale opérationnelle de l'aménagement du territoire, du logement, du patrimoine et de l'énergie Agence wallonne du Patrimoine (AWaP) Rue des Brigades d'Irlande, 1 B-5100 Jambes IMPRESSION, DIFFUSION ET VENTE ÉDITEUR RESPONSABLE Service publications Jean Plumier, Résidence du Grand Cortil Inspecteur général-expert Place des Célestines, 21 (derrière l'hôtel Ibis) B-5000 Namur COORDINATION ÉDITORIALE Tél. -

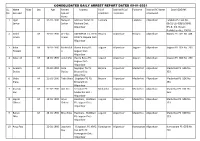

Consolidated Daily Arrest Report Dated 09-01-2021 Sl

CONSOLIDATED DAILY ARREST REPORT DATED 09-01-2021 SL. Name Alias Sex Age Father/ Address PS of District/PC of Ps Name District/PC Name Case/ GDE Ref. No Accused Spouse residence residence of Accused Name 1 Ujjal M 25-01-1900 Narayan Jateswar Bazar PS: Falakata Falakata Alipurduar Falakata PS Case No : Sarkar Sarkar Falakata Dist.: 06/21 US-498(A)/304B Alipurduar IPC & 3/4 Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961Â 2 Sushil M 30-01-1900 Lt- Elias RAHIMPUR T.G. NEW Birpara Alipurduar Birpara Alipurduar Birpara PS GDE No. 448 Oraon Oraon LINE PS: Birpara Dist.: Alipurduar 3 Babu M 18-01-1900 Motizuddi Jharna Busty PS: Jaigaon Alipurduar Jaigaon Alipurduar Jaigaon PS GDE No. 200 Hossain n Jaigaon Dist.: Alipurduar 4 Sukur Ali M 18-01-1900 Jainal Mia Jharna Busty PS: Jaigaon Alipurduar Jaigaon Alipurduar Jaigaon PS GDE No. 200 Jaigaon Dist.: Alipurduar 5 Gouatm M 09-02-1900 Saila Gopalpur TG PS: Birpara Alipurduar Madarihat Alipurduar Madarihat PS GDE No. Dorjee Dorjee Birpara Dist.: 353 Alipurduar 6 Shibu M 22-01-1900 Tetla Jhara Gopalpur TG PS: Birpara Alipurduar Madarihat Alipurduar Madarihat PS GDE No. Jhara Birpara Dist.: 353 Alipurduar 7 Ananda M 01-02-1900 Anil Das Sishubari PS: Madarihat Alipurduar Madarihat Alipurduar Madarihat PS GDE No. Das Madarihat Dist.: 353 Alipurduar 8 Jogesh M 19-01-1900 Arjun Hasimara, Haldibari Jaigaon Alipurduar Madarihat Alipurduar Madarihat PS GDE No. Chhetri Chhetri PS: Jaigaon Dist.: 353 Alipurduar 9 Barsat M 24-01-1900 Birsa Ekka Hasimara, Haldibari Jaigaon Alipurduar Madarihat Alipurduar Madarihat PS GDE No.