Mapping out Social Change in South India a Geographic Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pathanamthitta

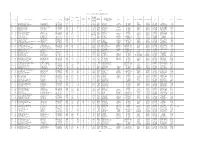

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

Carrying Capacity Assessment for Religious Crowd Management - an Application to Sabarimala Mass Gathering Pilgrimage, India

International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Volume 8 Issue 8 Article 8 2020 Carrying Capacity Assessment for Religious Crowd Management - An Application to Sabarimala Mass Gathering Pilgrimage, India Faisel T. Illiyas Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, [email protected] Shibu K. Mani CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Kengeri Campus, Bengaluru, [email protected] Naveen Babu Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp Part of the Emergency and Disaster Management Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation Illiyas, Faisel T.; Mani, Shibu K.; and Babu, Naveen (2020) "Carrying Capacity Assessment for Religious Crowd Management - An Application to Sabarimala Mass Gathering Pilgrimage, India," International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage: Vol. 8: Iss. 8, Article 8. doi:https://doi.org/10.21427/82rw-fx96 Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp/vol8/iss8/8 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. © International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage ISSN : 2009-7379 Available at: http://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp/ Volume 8(viii) 2020 Carrying Capacity Assessment for Religious Crowd Management - An Application to Sabarimala Mass Gathering Pilgrimage, India Faisel T. Illiyas Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai [email protected] Shibu K. Mani CHRIST University, School of Engineering and Technology, Bengaluru [email protected] Naveen Babu Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam [email protected] Crowd Management is always a challenging task when people gather in large numbers. Crowd disasters in India, including recurring incidents at religious venues, demands a crowd management system developed on the characteristics of the place, event, and participants. -

4/18/2015 Auction Catalog Report

4/18/2015 Auction Catalog Report 95764 Auction Details Auction No MSTC/BLR/DIVISIONAL FOREST OFFICE KOTTAYAM/4/INDIA/15-16/1139[95764] Opening Date & Time 30-04-2015::11:00:00 Closing Date & Time 30-04-2015::15:30:00 Inspection From Date 17-04-2015 Inspection Closing Date 29-04-2015 Seller Details Seller/Company Name DIVISIONAL FOREST OFFICE KOTTAYAM Location INDIA Street 2nd FLOOR, CIVIL STATION,KOTTAYAM City KOTTAYAM - 686002 Country INDIA Telephone 04812582886 Fax 04812562276 Email [email protected] Contact Person DIVISIONAL FOREST OFFICER, KOTTAYAM LOT NO[PCB GRP]/LOT NAME LOT DESC QUANTITY ED/(ST/VAT) LOCATION Lot Type: Teak Poles III Lot No: 26 Total no of logs= 50 As Applicable / 1948 Kalaketty Dumping Depot, Kalaketty [Latitude: 9.445889 PCB GRP :[PRE-BID Dumping Depot 02] 1948 TP Kalaketty FFA, 50 NO 14.5% Longitude: 76.934361] State :Kerala Erumely Range Lot Name: Teak Poles III Lot Type: Teak Poles III Lot No: 27 Total no of logs= 50 As Applicable / PCB GRP :[PRE-BID Dumping Depot 02] 1948 TP Kalaketty FFA, 50 NO 1948 Kalaketty Dumping Depot State :Kerala 14.5% Erumely Range Lot Name: Teak Poles III Lot Type: Teak Poles III Lot No: 28 Total no of logs= 50 As Applicable / PCB GRP :[PRE-BID Dumping Depot 02] 1948 TP Kalaketty FFA, 50 NO 1948 Kalaketty Dumping Depot State :Kerala 14.5% Erumely Range Lot Name: Teak Poles III Lot Type: Teak Poles III Lot No: 29 Total no of logs= 50 As Applicable / PCB GRP :[PRE-BID Dumping Depot 02] 1948 TP Kalaketty FFA, 50 NO 1948 Kalaketty Dumping Depot State :Kerala 14.5% Erumely Range -

District Census Handbook

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-B SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. Contents Pages 1 Foreword 1 2 Preface 3 3 Acknowledgement 5 4 History and Scope of the District Census Handbook 7 5 Brief History of the District 9 6 Administrative Setup 12 7 District Highlights - 2011 Census 14 8 Important Statistics 16 9 Section - I Primary Census Abstract (PCA) (i) Brief note on Primary Census Abstract 20 (ii) District Primary Census Abstract 25 Appendix to District Primary Census Abstract Total, Scheduled Castes and (iii) 33 Scheduled Tribes Population - Urban Block wise (iv) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes (SC) 41 (v) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Tribes (ST) 49 (vi) Sub-District Primary Census Abstract Village/Town wise 57 (vii) Urban PCA-Town wise Primary Census Abstract 89 Gram Panchayat Primary Census Abstract-C.D. -

(Coleoptera: Dytiscidae), Predatory to Aedes Albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) from the Foothills of Western Ghats, Kerala, India

Volume 2- Issue 3: 2018 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.02.000767 Adil Bashir. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res ISSN: 2574-1241 Research Article Open Access Description of a New Species, Platynectes Sahyadriensis (Coleoptera: Dytiscidae), Predatory to Aedes Albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) from the Foothills of Western Ghats, Kerala, India Adil Bashir1*, N Pradeep Kumar1 and Anisa B Khan2 1Vector Control Research Centre Field Station (ICMR), Kottayam, India 2Department of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Pondicherry University, India Received: February 02, 2018; Published: February 16, 2018 *Corresponding author: Adil Bashir, Vector Control Research Centre Field Station (ICMR), Kottayam, India, Email: Abstract We describe a new species of Dytiscidae beetle belonging to the Genus Platynectes from the mid high land region of Kerala, on the foothills Western Ghats, India. Western Ghats is the second largest mountainous belt in India on the western side of the Deccan Plateau and is described as one of the eight “Hottest bio-diversities in the world”. About 80.0 % of rubber crop in the Country is cultivated in the mid high land region of Western Ghats in Kerala and its plantations had been recorded to be the important breeding grounds of Aedes Albopictus vector species. Ae. albopictus immature in their key breeding habitats. Morphological characters of both male and female specimens of the beetle are described. Its morphologic characteristics precisely matched withThe newthe genusDytiscid Platynectes species has been reported to be an efficient natural predator of Platynectes by the Natural History Museum, London (NHM). Voucher specimens of the species are deposited with the museum of NHM, London and the Vector Control Research Centre (ICMR), Puducherry,. -

A Study from Flood Affected Areas in Ranni and Seasonal Water

Journal of Pediatric Neurology Resources, and Recycling Medicine and waste Management Pollution of Water bodies – A study from flood affected areas in Ranni and Seasonal water quality analysis of Pampa river from Erumely (Kottayam District) and Ranni (Pathanamthitta District), Kerala, India Dr.R.Aruna Devy Department of Zoology, St.Thomas College, Ranni, PathanmathittaDist., Kerala, India PIN – 689673 Abstract: Physical and chemical parameters degrade water causing health issues in living organisms. The present study examines the variation in these parameters in Pampa River at Ranny. Water were collected from five different sources at Mamukku,Ranny and tested at CEPCI Kollam. The study showed that the water quality at Ranny is fit for domestic use in terms of heavy metals. But BOD levels were elevated due to the pressure of organic waste that could have been entered due to the presence of chemical and sewage wastes in water bodies at Ranny. Among the five heavy metals (Cadmium, Chromium, Lead, Mercury and Copper) Copper and Chromium were below the standard limit and the other three heavy metals Lead, Cadmium and Mercury was below detected level.The regular water treatment methods adopted in the area due to recent flood may be the result of water quality in Ranny with respect to heavy metals. The physical parameters like pH of water sources in Ranny is normal except well water which slightly acidic due to chemicals runoff and wastewater discharge. The TDS levels are normal in all five sources but BOD levels are elevated due to the presence of organic wastes entered from chemical and sewage disposal in water bodies. -

Mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) Fauna in Alappuzha and ISSN 2320-7078 JEZS 2013; 1 (6): 134-137 Kottayam District of the Kerala State, South India

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2013; 1 (6): 134-137 Mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) fauna in Alappuzha and ISSN 2320-7078 JEZS 2013; 1 (6): 134-137 Kottayam district of the Kerala state, south India © 2013 JEZS 2013 Received 11-12-2013 R. Balasubramanian, Nikhil T.L. Accepted: 31-12-2013 ABSTRACT The study was conducted to look at the mosquito fauna in different sites of Alappuzha and Kottayam R. Balasubramanian National Institute of virology, districts, Kerala state to generate information on the diversity of mosquitoes. A total of 44 species of Kerala unit, Alappuzha 688 005, mosquitoes belonging to 21 subgenera and 11 genera were recorded in Alappuzha district and 21 Kerala, India. species of mosquitoes belonging to 14 subgenera and 9 genera were recorded in Kottayam districts. Email: [email protected] The genus Aedes, Anopheles, Mansonia, Heizmannia, Culex, Ficalbia, Uranotaenia, Tripteroides, Armigeres, Coquillettidia, and Mimomyia were recorded in Alappuzha district. Aedes, Anopheles, Nikhil T.L. Armigeres, Culex, Heizmannia, Tripteroides, Toxorhynchites and Uranotaenia were recorded in National Institute of virology, Kottayam district. Species common to both districts were Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus), Aedes albopictus Kerala unit, Alappuzha 688 005, (Skuse), Aedes vittatus (Bigot), Armigeres subalbatus (Coquillett), Culex fuscanus (Wiedemann), Kerala, India. Culex quinquefasciatus (Say), Culex tritaeniorhynchus (Giles), Heizmannia greenii (Theobald), Heizmannia indica (Theobald) and Toxorhynchites affinis (Edwards). Paddy field, mud pools, fallow fields, man-made artificial containers were the common breeding area in Alappuzha district and in Kottayam district tree holes, coconut shells, artificial containers and leaf axils were the main breeding habitats. Keywords: Mosquito fauna, Alappuzha, Kottayam, Aspirator. 1. -

1St Kottayam District Senior Baseball Championship 2015-16

Page 1 of 2 1st Kottayam District Senior Baseball Championship 2015-16 Girideepam school ground, Kottayam 04-Dec-2016 Assumption college changnacherry (KTM161001) - Club Team Category: Female | Manager: | Coach: | Position: Runner Up Name: JOHNA MOL THOMAS Name: ARCHANAMOL P A Reg No: 001515 Cert No: Reg No: 001516 Cert No: DOB: 21-Jul-1995 DOB: 09-May-1995 Guardian: THOMAS (FATHER ) Guardian: AJI P P (FATHER ) Address: THUNDIYIL, KARAYATHUMCHAL , CHEMMENTHOTTY Address: PANAMPARAMBIL, KANAMALA SREEKANDAPURAM - 670631, KANNUR KALAKETTY, KOTTYAM - 686510, KOTTAYAM Name: PUNNYA R KRISHNAN Name: PRIYA C C Reg No: 001520 Cert No: Reg No: 001523 Cert No: DOB: 23-May-1995 DOB: 06-Jan-1993 Guardian: RADHAKRISHNA PILLAI (FATHER ) Guardian: KUTTIYARAPPAN (FATHER ) Address: THIRUMANASSERI , OORACKARY Address: VAYAD, VILANGAD RAMANKARY - 689595, ALAPPUZHA KALLACHI - 670306, KOZHIKODE Name: MANIMEGHALA. T.D Name: ANJALI SAJI Reg No: 002876 Cert No: Reg No: 002862 Cert No: DOB: 01-Feb-1996 DOB: 07-Feb-1997 Guardian: DASAPPAN T.R (FATHER) Guardian: SAJI A P (FATHER) Address: THUNDIYIL EZHAKADAV, NALUKODY P.O Address: ARACKAL, NELLIMATTOM CHANGANASSERY - 686548, KOTTAYAM KAITHAMATTOM - 686693, ERNAKULAM Name: ANGEL C FRANCIS Name: RESHMA RAVEENDRAN Reg No: 002864 Cert No: Reg No: 002865 Cert No: DOB: 28-Feb-1997 DOB: 20-Feb-1996 Guardian: BIJI C FRANCIS (FATHER) Guardian: RAVEENDRAN NAIR (FATHER) Address: CHEMPILAKAM, ANIKAD Address: SHANMUGHAVILASAN, KALAVARAKKONAM MALLAPPALLY - 689589, PATHANAMTHITTA POOZHANADU (PO) - 695125, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM Name: -

Agenda and Notes of the Meeting of the Rta Kottayam Dated 30/11/2017

1 AGENDA AND NOTES OF THE MEETING OF THE RTA KOTTAYAM DATED 30/11/2017. Item No - 01 G1/109928/2017/K Agenda-To consider the application for the grant of fresh regular permit to SC KL 34 C 1427 / another suitable vehicle to operate on the route KUZHIMAVU – ERUMELY Via, Koruthodu, Panackachira, Vandanpathal, Mundakayam, Kannimala, Pulikkunnu, Kottaramkada as Ordinary Service Applicant- Sri. Binu P S, Pazhoor [H], Palampra P.O., Kanjirappally. Proposed Timings Kuzhimavu Mundakayam Erumely A D A D A D 6.05[S] 6.43 7.00 7.33 8.16 7.43 9.20 8.42 9.30 10.08 11.03 10.25 11.20 11.58 12.40 1.13 2.36 2.03 3.09 3.42 4.53 4.20 5.35 6.08 6.58 6.25 7.55 [H] 7.17 Notes- This is an application for the grant of a of a fresh regular permit to SC KL 34 C 1427 / another suitable vehicle to operate on the route KUZHIMAVU – ERUMELY Via, Koruthodu, Panackachira, Vandanpathal, Mundakayam, Kannimala, Pulikkunnu, Kottaramkada as Ordinary Service. The enquiry report of MVI Kanjirappally revealed the following. 1. Total distance of the route : 28.2 Kms. 2. Intra/ Inter District route : Intra District. 3. Details of Virgin Portion : Nil 2 4. Details of Road Fitness certificate : N.A. 5. Details of Overlapping : Total overlapping is 150 meter ie, 0.53 % of the total route length [28.2 km] which is within the permissible limit. 1) Route portion of 150 meter from Mundakayam B S Jn. -

Sheet1 Page 1 LIST of SCHOOLS in KOTTAYAM DISTRICT 10 Sl. No

Sheet1 LIST OF SCHOOLS IN KOTTAYAM DISTRICT No of Students HS/HSS/ Year of VHSS/H Name of Panch- Std. Std. Boys/ 10 Sl. No. Name of School Address with Pincode Phone No Establishm SS ayat /Muncipality/ Block Taluk Name of Parliament Name of Assembly DEO AEO MGT Remarks (From) (To) Girls/ Mixed ent Boys Girls &VHSS/ Corporation TTI 10 1 Areeparambu Govt. HSS Areeparambu P.O. 0481-2700300 1905 42 36 I XII HSS Mixed Manarcadu Pallam Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Pampady Govt 10 2 Arpookara Medical College VHSS Gandhinagar P.O. 0481-2597401 1966 73 33 V XII HSS&VHSS Mixed Arpookara Ettumanoor Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 3 Changanacherry Govt. HSS Changanacherry P.O. 0481-2420748 1871 43 23 V XII HSS Mixed Changanacherry ( M ) Changanacherry Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Changanassery Govt 10 4 Chengalam Govt. HSS Chengalam South P.O. 0481-2524828 1917 127 107 I XII HSS Mixed Thiruvarpu Pallam Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 5 Karapuzha Govt. HSS Karapuzha P.O. 0481-2582936 1895 56 34 I XII HSS Mixed Kottayam( M ) Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 6 Karipputhitta Govt. HS Arpookara P.O. 0481-2598612 1915 74 44 I X HS Mixed Arpookara Ettumanoor Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 7 Kothala Govt. VHSS S.N. Puram P.O. 0481-2507726 1912 48 64 I XII VHSS Mixed Kooroppada Pampady Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Pampady Govt 10 8 Kottayam Govt. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Rta, Kottayam Held on 26-02-2021 at Jilla Panchayath Hall, Kottayam

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE RTA, KOTTAYAM HELD ON 26-02-2021 AT JILLA PANCHAYATH HALL, KOTTAYAM ****************************************************************************** Item No. 1 J1/KL35J0678/2020/K ****************************************************************************** Heard the learned counsel represented for the applicant and representative of the KSRTC and objectors. This is an application for the grant fresh regular permit in respect of SC KL 35 J 0678/another suitable SC to operate on the route Kanjiramkavala – Pala via Pazhukkakanam, Illickalkallu, Mankombu Temple, Erattupetta and Bharananganam as Ordinary Service. This Authority considered the application and verified the connected documents and the enquiry report and all objections in detail. The portion of route from Maharani Junction to Kottaramattom BS (1.85 KMs) overlaps on Kottayam – Kattappana notified Scheme. The total distance of overlapping in the proposed route is 1.85 KM ie, 4.51 % of the total route length of 41 km and the same is under the permissible limit as per GO(P) No. 8/2017 Trans dated 23/03/2017. The enquiry officer reported that in the proposed portion of route from Kanjiramkavala to Pazhukkakkanam is ill served and granting a permit to this route is beneficial to public including students. Illickalkallu is a famous tourist place and it is beneficial to the tourists. At present there is no stage carriage service between Kalamukku and Pazhakkakkanam. With regard to the objections, the representative of the KSRTC pointed out that the major intermediate points between Erattupetta and Pala are not mentioned and therefore the exact route cannot be ascertained. There are objections against the proposed timings too. On verification of proposed timings, it is noted that more trips are offered between the well served sector between Pala and Erattupetta and less trips to the ill served sector. -

Sabarimala Pilgrimage

MANAGING RELIGIOUS CROWD SAFELY CRISIS MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR SABARIMALA PILGRIMAGE PROJECT REPORT Institute of Land and Disaster Management Department of Revenue and Disaster Management Government of Kerala PROJECT TEAM Faisel T Illiyas Assistant Professor & Project In Charge Institute of Land and Disaster Management Government of Kerala & Naveen Babu Project Fellow Sabarimala Crisis Management Project Institute of Land and Disaster Management CONTENTS Preface Sabarimala Pilgrimage Sabarimala Crisis Management Plan I. Purpose II. Definition of “Crisis” III Objectives IV. Authority V Familiarization VI Hazard Analysis Sector I: Sannidanam Sector Ii: Trekking Paths Sector Iii: Pamba VII Crisis Management Plan for Sannidanam VIII. Incident Control and Crisis Communication IX. Evacuation X. Medical Emergencies and Mass Casualty Management Triage Process Emergency Medical Transportation from Sannidanam Arrangements Required at Pamba XI. Disaster Specific Response XII. Documenting a Crisis or Emergency XIII. What Marks the End of a Crisis? ANNEXURE I. Recommendations ANNEXURE II. Makaravilakku disaster preparedness ANNEXURE III: Safety Guideline for Disaster Mitigation ANNEXURE IV: Establishment and Function of Emergency Operation Centre (EOC) ANNEXURE V: Emergency Contact Numbers PREFACE Mass gathering in remote locations under limited infrastructural facilities often pose serious threat to human stampedes and other disasters. Hundreds of people die every year due to human stampedes occurring in religious festivals in India. Most of the crowded religious events involve simultaneous movement of very large groups of people in various directions. Sabarimala pilgrimage season which attracts lakhs of people from South India is one of the hotspots of human stampede due to various reasons. Various Departments of Government of Kerala work together in Sabarimala for the safe conduct of pilgrimage season.