Clarence Darrow Story Script by Jack Marshall and Paul Morella Starring Paulby Morella

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESTELLE PARSONS & NAOMI LIEBLER Monday, April 13

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ENGAGING PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD IN COLLABORATION WITH THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION THE LAMBS, NEW YORK CITY ESTELLE PARSONS & NAOMI LIEBLER Monday, April 13 For this special gathering, the GUILD is delighted to join forces with THE LAMBS, a venerable theatrical society whose early leaders founded Actors’ Equity, ASCAP, and the Screen Actors Guild. Hal Holbrook offered Mark Twain Tonight to his fellow Lambs before taking the show public. So it’s hard to imagine a better THE LAMBS setting for ESTELLE PARSONS and NAOMI LIEBLER to present 3 West 51st Street a dramatic exploration of “Shakespeare’s Old Ladies.” A Manhattan member of the American Theatre Hall of Fame and a PROGRAM 7:00 P.M. former head of The Actors Studio, Ms. Parsons has been Members $5 nominated for five Tony Awards and earned an Oscar Non-Members $10 as Blanche Barrow in Bonnie and Clyde (1967). Dr. Liebler, a professor at Montclair State, has given us such critically esteemed studies as Shakespeare’s Festive Tragedy. Following their dialogue, a hit in 2011 at the New York Public Library, they’ll engage in a wide-ranging conversation about its key themes. TERRY ALFORD Tuesday, April 14 To mark the 150th anniversary of what has been called the most dramatic moment in American history, we’re pleased to host a program with TERRY ALFORD. A prominent Civil War historian, he’ll introduce his long-awaited biography of an actor who NATIONAL ARTS CLUB co-starred with his two brothers in a November 1864 15 Gramercy Park South benefit of Julius Caesar, and who restaged a “lofty Manhattan scene” from that tragedy five months later when he PROGRAM 6:00 P.M. -

Gigi Starring Jean-Pierre Aumont Little Theatre on the Square

Eastern Illinois University The Keep 1974 Programs 1974 8-27-1974 Gigi starring Jean-Pierre Aumont Little Theatre on the Square Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/little_theatre_1974_programs Part of the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Little Theatre on the Square, "Gigi starring Jean-Pierre Aumont" (1974). 1974 Programs. 8. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/little_theatre_1974_programs/8 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 1974 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1974 Programs by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Guy S. Little, Jr - * . - '- - 9 !k I+#+: Yre~ents.~. .- . Ir L2rner and Loewe's - -- \ Book and Lyrics by Music by Alan Jay Lerner Frederick Lc Based on a novel by Colette As produced by Edwin Lester for the Los and San Francisco Civic Light Opera And fby Saint Subber for Broadway Also Starring. DAVID WATSON with PAMELA DANSER MARY BEST 'I Bernard Erhard John Kelso Dennis GridL * and Lorraine Denham as Gigi ! l~irectedby CHARLES ABBOTT[ Choreographed by DENNIS GRAMALDI Ptnduction Derkned by -ROBERT SOULE .. - '~ortumerDer&ned by MATHRN JOHN HOFFMAN Ill Lighting Desbned by KIM HANSON Mbsicol Director BRUCE KlRLE Production Stage Manager Tech nlcal Director C. G. CARLSON JEROME ROBENBERGER - As~istantto the Musical Director . Assistant to the Costumer Barbara Bossert Jones CARL QSHEA , "GIGI' 4 The Little al&ttre's 18th Seamfi Our 44th Yew P. N. ~IIESCHCO. Vidt our nm location 113 Esst Joffwum Sullivan Phone 728-71 13 Family I Routes 121 and 32 Sullivan Shoe Center Hush Puppk U~arrnStop Jarrnan Rmd Wing Air Conditioned Chlldnn's Stmp Master Tokvkion West Side of Square, Sullivan Conviently located near Phone: (217)728-7750 Lake Shelbyville. -

2010 16Th Annual SAG AWARDS

CATEGORIA CINEMA Melhor ator JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) Melhor atriz SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) Melhor ator coadjuvante MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey – “UM OLHAR NO PARAÍSO” ("THE LOVELY BONES") (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) Melhor atriz coadjuvante PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) Melhor elenco AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. -

71St Cover F

SEVENTY-FIRST STREET 71VOLUME 12 ● NUMBER 2 MMC Gallery Named Hewitt Gallery of Art TABLE OF CONTENTS MMC Gallery Named Hewitt Gallery of Art In honor of Marsha A. Hewitt ’67 and husband Carl’s generous donation SEVENTY-FIRST STREET to the College, the MMC Gallery of Art has a new name. Turn the page to learn more about this couple’s deep commitment to MMC . 2 Grant Funds One MMC Student’s Passion for Science VOLUME 12 ● NUMBER 2 Elizabeth Perez ’06 had a unique opportunity to work full-time FALL 2004 on her research in molecular neuroscience this summer 71 thanks to a grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb . 4 Editor: Erin J. Sauer Design: Connelly Design Fundraising Recap . 6 The Tamburro Family’s Legacy 71st Street is published twice a Impact of Annual Fund Donations year by the Office of Institutional Advancement at Marymount Greek Student Attends MMC Thanks to Niarchos Foundation Manhattan College. The title SAT Scores of MMC Freshman on the Rise recognizes the many alumni and faculty who have come to refer Spring Round-Up affectionately to the college The events and happenings that shaped our spring . 8 by its Upper East Side address. Campus Notes Marymount Manhattan College 221 East 71st Street Faculty announcements, notable lectures, theatre events, award winners, New York, NY 10021 and other interesting news from around campus . 14 (212) 517-0450 Class Notes Find out what your fellow alumni are up to . 18 The views and opinions expressed by those in this magazine are Alumni Calendar . 24 independent and do not necessarily represent those of Marymount Manhattan College. -

Hal Holbrook

HAL HOLBROOK Hal Holbrook was born in Cleveland in 1925, but raised mostly in South Weymouth, Massachusetts. His people had settled there in 1635 and were, according to his grandfather, “some kind of criminals from England.” His mother disappeared when he was two, his father followed suit, so young Holbrook and his two sisters were raised by their grandfather. It was only later he found out that his mother had gone into show business. Holbrook, being the only boy, was the “white hope of the family.” Sent away at the age of 7 to one of the finer New England schools, he was beaten regularly by a Dickensian headmaster who, when forced to retire, committed suicide. But when he was 12 he was sent to Culver Military Academy, where he discovered acting as an escape from his disenchantment with authority. While not the model cadet, he believes the discipline he learned at Culver saved his life. In the summer of 1942 he got his first paid professional engagement playing the son in The Man Who Came To Dinner at the Cain Park Theatre in Cleveland at $15.00 per week. That fall, he entered Denison University in Ohio, majoring in Theatre under the tutelage of his lifelong mentor, Edward A. Wright. World War II pulled him out of there and put him into the Army Engineers for three years. The Mark Twain characterization grew out of an honors project at Denison University after the War. Holbrook and his first wife, Ruby, had constructed a two-person show, playing characters from Shakespeare to Twain. -

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2007 By: the Entire Membership HOUSE RESOLUTION NO. 58 a RESOLUTION CO

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2007 By: The Entire Membership To: Rules HOUSE RESOLUTION NO. 58 1 A RESOLUTION COMMENDING MR. HAL HOLBROOK AND CONGRATULATING 2 HIM UPON ALL HIS ACCOMPLISHMENTS AND CAREER SUCCESSES AS AN ACTOR. 3 WHEREAS, Harold Rowe Holbrook, Jr., whom we have come to know 4 as Hal Holbrook, was born on February 17, 1925, in Cleveland, 5 Ohio, to Harold Rowe Holbrook and Aileen Davenport; and 6 WHEREAS, Hal Holbrook entered Denison University in 1942, 7 left to serve three years in the United States Army as an engineer 8 during World War II, and subsequently graduated from Denison 9 University in 1948, where his participation in an honors program 10 on Mark Twain would launch his long career as a performer; and 11 WHEREAS, Mr. Holbrook, as he told Bill Moyers in an 12 interview, presented his first solo performance as Mark Twain at 13 Lock Haven State Teachers College in Pennsylvania in 1954, as a 14 "desperate alternative to selling hats or running elevators to 15 keep his family alive"; and 16 WHEREAS, later Ed Sullivan saw Holbrook's performance and 17 invited him on the Ed Sullivan Show where Holbrook received his 18 first national exposure as Twain on February 12, 1956; and 19 WHEREAS, eventually more performances and other venues would 20 solidify Mr. Holbrook's "Mark Twain Tonight" as the most enduring 21 one man show in theatrical history and would inspire many more 22 actors and actresses to bring to life characters of history to the 23 world's theater goers; and 24 WHEREAS, Mr. -

1 Nominations Announced for the 19Th Annual Screen Actors Guild

Nominations Announced for the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Ceremony will be Simulcast Live on Sunday, Jan. 27, 2013 on TNT and TBS at 8 p.m. (ET)/5 p.m. (PT) LOS ANGELES (Dec. 12, 2012) — Nominees for the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® for outstanding performances in 2012 in five film and eight primetime television categories as well as the SAG Awards honors for outstanding action performances by film and television stunt ensembles were announced this morning in Los Angeles at the Pacific Design Center’s SilverScreen Theater in West Hollywood. SAG-AFTRA Executive Vice President Ned Vaughn introduced Busy Philipps (TBS’ “Cougar Town” and the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® Social Media Ambassador) and Taye Diggs (“Private Practice”) who announced the nominees for this year’s Actors®. SAG Awards® Committee Vice Chair Daryl Anderson and Committee Member Woody Schultz announced the stunt ensemble nominees. The 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® will be simulcast live nationally on TNT and TBS on Sunday, Jan. 27 at 8 p.m. (ET)/5 p.m. (PT) from the Los Angeles Shrine Exposition Center. An encore performance will air immediately following on TNT at 10 p.m. (ET)/7 p.m. (PT). Recipients of the stunt ensemble honors will be announced from the SAG Awards® red carpet during the tntdrama.com and tbs.com live pre-show webcasts, which begin at 6 p.m. (ET)/3 p.m. (PT). Of the top industry accolades presented to performers, only the Screen Actors Guild Awards® are selected solely by actors’ peers in SAG-AFTRA. -

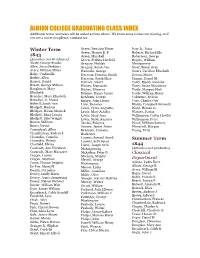

ALBION COLLEGE GRADUATING CLASS INDEX Additional Terms and Years Will Be Added As Time Allows

ALBION COLLEGE GRADUATING CLASS INDEX Additional terms and years will be added as time allows. We know some names are missing, so if you see a correction please, contact us. Winter Term Green, Denslow Elmer Pray Jr., Isaac Green, Harriet E. F. Roberts, Richard Ely 1843 Green, Marshall Robertson, George [Attendees not Graduates] Green, Perkins Hatfield Rogers, William Alcott, George Brooks Gregory, Huldah Montgomery Allen, Amos Stebbins Gregory, Sarah Ann Stout, Byron Gray Avery, William Miller Hannahs, George Stuart, Caroline Elizabeth Baley, Cinderella Harroun, Denison Smith Sutton, Moses Barker, Ellen Harroun, Sarah Eliza Timms, Daniel M. Barney, Daniel Herrick, Albert Torry, Ripley Alcander Basset, George Stillson Hickey, Manasseh Torry, Susan Woodbury Baughman, Mary Hickey, Minerva Tuttle, Marquis Hull Elizabeth Holmes, Henry James Tuttle, William Henry Benedict, Mary Elizabeth Ketchum, George Volentine, Nelson Benedict, Jr, Moses Knapp, John Henry Vose, Charles Otis Bidwell, Sarah Ann Lake, Dessoles Waldo, Campbell Griswold Blodgett, Hudson Lewis, Cyrus Augustus Ward, Heman G. Blodgett, Hiram Merrick Lewis, Mary Athalia Warner, Darius Blodgett, Mary Louisa Lewis, Mary Jane Williamson, Calvin Hawley Blodgett, Silas Wright Lewis, Sarah Augusta Williamson, Peter Brown, William Jacobs, Rebecca Wood, William Somers Burns, David Joomis, James Joline Woodruff, Morgan Carmichael, Allen Ketchum, Cornelia Young, Urial Chamberlain, Roderick Rochester Champlin, Cornelia Loomis, Samuel Sured Summer Term Champlin, Nelson Loomis, Seth Sured Chatfield, Elvina Lucas, Joseph Orin 1844 Coonradt, Ann Elizabeth Mahaigeosing [Attendees not graduates] Coonradt, Mary Margaret McArthur, Peter D. Classical Cragan, Louisa Mechem, Stanley Cragan, Matthew Merrill, George Department Crane, Horace Delphin Washington Adkins, Lydia Flora De Puy, Maria H. Messer, Lydia Allcott, George B. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

Saluting the Classical Tradition in Drama

SALUTING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ILLUMINATING PRESENTATIONS BY The Shakespeare Guild IN COLLABORATION WITH The National Arts Club The Corcoran Gallery of Art The English-Speaking Union Woman’s National Democratic Club KATHRYN MEISLE Monday, February 6 KATHRYN MEISLE has just completed an extended run as Deborah in ROUNDABOUT THEATRE’s production of A Touch of the Poet, with Gabriel Byrne in the title part. Last year she delighted that company’s audiences as Marie-Louise in a rendering of The Constant Wife that starred Lynn Redgrave. For her performance in Tartuffe, with Brian Bedford and Henry Goodman, Ms. Meisle won the CALLOWAY AWARD and was nominated for a TONY as Outstanding Featured Actress. Her other Broadway credits include memorable roles in London Assur- NATIONAL ARTS CLUB ance, The Rehearsal, and Racing Demon. Filmgoers will recall Ms. Meisle from You’ve Got Mail, The Shaft, and Rosewood. Home viewers 15 Gramercy Park South Manhattan will recognize her for key parts in Law & Order and Oz. And those who love the classics will cherish her portrayals of such heroines as Program, 7:30 p.m. Celia, Desdemona, Masha, Olivia at ARENA STAGE, the GUTHRIE THEATER, MEMBERS, $25 OTHERS, $30 LINCOLN CENTER, the NEW YORK SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL, and other settings. E. R. BRAITHWAITE Thursday, February 23 We’re pleased to welcome a magnetic figure who, as a young man from the Third World who’d just completed a doctorate in physics from Cambridge, discovered to his consternation that the color of his skin prevented him from landing a job in his chosen field. -

July 25, 1968

1 Worrie r Rejects 3W K^*P fSpeTT-"" Tuit ion Protest Stokes Accuses By DAVE COLKER Slimmer Stajf Writer Negro Militants Undergraduate Student Government President Jim CLEVELAND, Ohio t'.-P) — Mayor Carl any more of the burning and looting that Womer announced Tuesday that there would be no student ¦ B. Stokes blamed a "small and determined" erupted on a small scale during the shooting. rally this week (o protest the University's proposed tuition K? '- i| - ;'. ¦ increase. c '"y ' band of Negro militants yesterday for am- Trouble in the Negro slum, which was Speculation arose last week that a student protest Bb&\'*~' , bushing police and touching off a bloody untouched during the Hough rioting two rally would be organized to confront the University night of gunfire that took 10 lives. A Black years ago, began shortly after sundown Board of Trustees which will consider the tuition increase Nationalist was quoted as saying he led Tuesday when, according to police, snipers when they meet tomorrow in Erie. Womer ended the spec- the uprising. opened fire on policemen trying to remove ulation when he addressed the Summer Coordinating Com- ¦St. mittee, a group of student leaders and administration per- Seven of the dead were Negroes, two an abandoned auto. sonnel. of them snipers in African garb. Three while Sporadic fire still crackled at dawn from "The Board of Trustees are meeting in Erie, not at Uni- policemen were killed and 19 others wound- t he are at East 105th Street and Superior versity Park," Womer said. "This makes a demonstration &*SmKiiiilllir ed, before drenching rain, police sharp- Avenue. -

CINE MEJOR ACTOR JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake

CINE MEJOR ACTOR JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) MEJOR ACTRIZ SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) MEJOR ACTOR DE REPARTO MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey - "THE LOVELY BONES" (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa - "INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS" (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MEJOR ACTRIZ DE REPARTO PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark - "INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS" (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MEJOR ELENCO AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. J.T.