Effective Use of Citizen Advisory Committees for Transit Planning and Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smart Location Database Technical Documentation and User Guide

SMART LOCATION DATABASE TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION AND USER GUIDE Version 3.0 Updated: June 2021 Authors: Jim Chapman, MSCE, Managing Principal, Urban Design 4 Health, Inc. (UD4H) Eric H. Fox, MScP, Senior Planner, UD4H William Bachman, Ph.D., Senior Analyst, UD4H Lawrence D. Frank, Ph.D., President, UD4H John Thomas, Ph.D., U.S. EPA Office of Community Revitalization Alexis Rourk Reyes, MSCRP, U.S. EPA Office of Community Revitalization About This Report The Smart Location Database is a publicly available data product and service provided by the U.S. EPA Smart Growth Program. This version 3.0 documentation builds on, and updates where needed, the version 2.0 document.1 Urban Design 4 Health, Inc. updated this guide for the project called Updating the EPA GSA Smart Location Database. Acknowledgements Urban Design 4 Health was contracted by the U.S. EPA with support from the General Services Administration’s Center for Urban Development to update the Smart Location Database and this User Guide. As the Project Manager for this study, Jim Chapman supervised the data development and authored this updated user guide. Mr. Eric Fox and Dr. William Bachman led all data acquisition, geoprocessing, and spatial analyses undertaken in the development of version 3.0 of the Smart Location Database and co- authored the user guide through substantive contributions to the methods and information provided. Dr. Larry Frank provided data development input and reviewed the report providing critical input and feedback. The authors would like to acknowledge the guidance, review, and support provided by: • Ruth Kroeger, U.S. General Services Administration • Frank Giblin, U.S. -

Homelessness in Transit Environments Volume I: Findings from a Survey of Public Transit Operators

UC Office of the President ITS reports Title Homelessness in Transit Environments Volume I: Findings from a Survey of Public Transit Operators Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/55d481p8 Authors Loukaitou-Sideris, Anastasia Wasserman, Jacob Caro, Ryan et al. Publication Date 2020-12-17 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California RESEARCH REPORT Institute of Transportation Studies Homelessness in Transit Environments Volume I: Findings from a Survey of Public Transit Operators Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Urban Planning, UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs Jacob Wasserman, Research Project Manager Ryan Caro, Graduate Student Researcher Hao Ding, Graduate Student Researcher UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies December 2020 Report No.: UC-ITS-2021-13 | DOI: 10.17610/T6V317 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. UC-ITS-2021-13 N/A N/A 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Homelessness in Transit Environments December 2020 Volume I: Findings from a Survey of Public Transit Operators 6. Performing Organization Code UCLA-ITS 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Ph.D., https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0186-4751; Jacob N/A Wasserman https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2212-5798; Ryan Caro, https://orcid. org/0000-0002-2795-7270; Hao Ding, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5286-3367 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. Institute of Transportation Studies, UCLA N/A 3320 Public Affairs Building 11. Contract or Grant No. Los Angeles, CA 90095-1656 UC-ITS-2021-13 12. -

JOINT SHORT RANGE TRANSIT PLANS for RTA and SLO TRANSIT Working Paper One: Overview of Existing Transit Service

JOINT SHORT RANGE TRANSIT PLANS FOR RTA AND SLO TRANSIT Working Paper One: Overview of Existing Transit Service Prepared for the San Luis Obispo Regional Transit Authority and for SLO Transit Prepared by Joint Short Range Transit Plans for RTA and SLO Transit WORKING PAPER ONE: OVERVIEW OF EXISTING TRANSIT SERVICE _________________________ Prepared for the San Luis Obispo Regional Transit Authority 179 Cross Street San Luis Obispo, CA 93401 805 • 781-4465 and for SLO Transit 919 Palm Street San Luis Obispo, CA 93401 805-781-7121 Prepared by LSC Transportation Consultants, Inc. 2690 Lake Forest Road, Suite C P. O. Box 5875 Tahoe City, California 96145 530 • 583-4053 and by AECOM, Inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 History and Governance of Transit Operators ............................................................ 1 2 San Luis Obispo Regional Transit Authority Services ....................................................... 5 San Luis Obispo Regional Transit Authority ................................................................ 5 Overall Service Description ......................................................................................... 5 Financial Information ................................................................................................ 18 -

Listing of PTMISEA Projects Allocated October 2011

Proposed PTMISEA Bond Allocation Assembly Senate Congressional CT Ref # County Grantee Project Total Distict District District Dist Del Norte Local Transportation Replacement Buses for Redwood Coast 1 Del Norte 1 4 1 1 $ 309, 447 Commission Transit 2 Humboldt City of Arcata 1 2 1 1 Replacement 35 foot Transit Bus $ 219, 006 3 Humboldt City of Eureka 1 2 1 1 GPS Tracking System $ 122, 982 4 Humboldt City of Eureka 1 2 1 1 Bus Stop Improvement Project $ 100,000 5 Humboldt Humboldt Transit Authority 1 2 1 1 GPS Tracking System $ 164,264 6 Humboldt Humboldt Transit Authority 1 2 1 1 Bus Stop Improvement Project $ 105,810 Purchase Five Replacement Buses for 7 Lake Lake Transit Authority 1 2 1 1 $ 309,288 LTA Plumas County Transportation 8 Plumas 1 3 4 2 Plumas County Bus Yard $ 243,930 Commission Passenger Accessibility & Loading 9 Shasta Redding Area Bus Authority 4 2 2 2 $ 260,000 Improvements 10 Shasta Redding Area Bus Authority 4 2 2 2 Downtown Transit Center Expansion $ 180,000 11 Shasta Redding Area Bus Authority 4 2 2 2 Maintenence Facility Lobby Renovation $ 57,181 Siskiyou County Local Transportation 12 Siskiyou 4 2 2 2 Purchase of Bus $ 219,272 Comm. Tehama County Transportation 13 Tehama 2 4 2 2 Bus Stop Improvements $ 148,134 Commission Tehama County Transportation 14 Tehama 2 4 2 2 Dispatching Software $ 70,000 Commission Tehama County Transportation 15 Tehama 2 4 2 2 Replace Small Paratrax Vehicle $ 60,000 Commission Trinity County Transportation 16 Trinity 1 4 2 2 Trinity Transit Bus $ 120,989 Commission Butte County Association of Design & Construction of Transit 17 Butte 2,3 4 2 3 $ 1,717,305 Governments Maintenance, Admin, & Operations Facility 18 El Dorado El Dorado County Transit Authority 4,10 1 4 3 Automatic Vehicle Location System $ 456,295 Gold Country Stage Bus Stop 19 Nevada County of Nevada 4 3 4 3 $ 322,501 Improvements Gold Country Stage Vehicle 20 Nevada County of Nevada 4 3 4 3 $ 55,000 Replacement Placer Co. -

Fy19-20 Low Carbon Transit Operations Program Allocation Award List

Caltrans-Division of Rail and Mass Transportation FY19-20 LOW CARBON TRANSIT OPERATIONS PROGRAM ALLOCATION AWARD LIST Disadvantaged Low 1/2 Mile Low- Community Income Income Buffer Total Project Project Benefit Benefit Benefit Request SB 1119 District Project ID Lead Agency: Project Name: Type: Project Description (Short): FY19-20 City of Arcata (Arcata Mad River Transit To allow Free Transit to encourage ridership on Arcata Mad River Transit NO YES NO #N/A 1 19-20-D01-001 System) AMRTS Free Fares Operations System $13,339 This project will provide reduced fares and free ticket vouchers to raise Humboldt Transit Reduced Fares and Free awareness of public transportation. This will give riders an opportunity to NO YES NO #N/A 1 19-20-D01-002 Authority Ticket Vouchers Operations try transit at no cost. $303,307 This project provides for the purchase and installation of a solar canopy to cover the bus parking lot. The canopy will provide enough electricity to power four electric buses and the operations facility. The canopy will also shade the lot, reducing the time buses are idling prior to inspection and NO YES NO #N/A 1 19-20-D01-003 Lake Transit Authority Solar Canopy Project Capital start-up. $102,736 The project will provide unlimited free use of Lake Transit Authority bus routes anywhere in Lake, Napa, or Mendocino counties for the following: Free Fares for Community (1) any Mendocino College or Woodland College student displaying a College Students and the valid student identification and (2) any child between the age of 7 and 17 NO YES NO #N/A 1 19-20-D01-004 Lake Transit Authority Summer Cruisin' Program Operations between June 15 and August 31 (known as the Summer Cruisin' Program) $23,351 RCTA will use LCTOP funding in a three-year bus electrification project, planning an installing an electric recharge facility and augmenting an FTA bus grant to purchase an electric powered vehicle. -

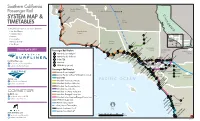

System Map & Timetables

To Oakland/ Southern California Seattle San Luis Obispo San Luis County Passenger Rail A A Obispo to Oakland/Sacramento Bakersfield C A SYSTEM MAP & A Grover Beach L Kern I County F O TIMETABLES Guadalupe-Santa Maria A R N Schedule information for trains between: I A • San Luis Obispo Santa Barbara County • Santa Barbara Lancaster A Lompoc-Surf M • Ventura • Los Angeles M Palmdale • Orange County Ventura County M Vincent Grade/Acton • San Diego Goleta Santa Barbara A A Santa ClaritaVia Princessa A Carpinteria M A M M Los Angeles Effective April 8, 2019 Moorpark Sylmar/ County San Bernardino Passenger Rail Station Ventura M Newhall San Fernando A Ventura-East M M to Albuquerque/ M A A M County ® A A M Sun Valley Chicago A Amtrak Coast Starlight M M M M M Burbank Airport North A A A M Burbank A A A Downtown A Amtrak Pacic Suriner® A M Simi Valley Chatsworth Northridge M Oxnard A PomonaClaremontMontclairUpland FontanaRialto C COASTER Camarillo Van Nuys El Monte Baldwin ParkCovina Rancho Cucamonga M San Bernardino Airport A Cal State L.A.M M M M M M M M M M PacificSurfliner.com A M M M San Miguel Island M M Metrolink Hollywood Burbank Glendale facebook.com/PacicSuriner M M M Pedley M M Riverside- S Montebello/ Downtown twitter.com/PacSuriners SPRINTER (Light Rail) Montebello/Commerce E. Ontario M Hunter Park/ CommerceIndustry Pomona Riverside Santa Rosa Island L.A. Union Station M Downtown UCR M Commerce M Anaheim M M M Canyon Moreno Valley/ Passenger Rail Service A M M Norwalk/ March Field N. -

SANTA MARIA-SAN LUIS OBISPO TRANSPORTATION CONNECTIVITY STUDY Final Report

SANTA MARIA-SAN LUIS OBISPO TRANSPORTATION CONNECTIVITY STUDY Final Report September 2017 Funding provided by: California Department of Transportation Strategic Partnerships Grant Program SANTA MARIA-SAN LUIS OBISPO TRANSPORTATION CONNECTIVITY STUDY FINAL REPORT Santa Barbara County Association of Governments Table of Contents Page 1 Executive Summary .........................................................................................................1-1 Analysis and Outreach ......................................................................................................................... 1-2 Recommendations .................................................................................................................................. 1-4 2 Planning Context .............................................................................................................2-1 SBCAG Plans .......................................................................................................................................... 2-1 SLOCOG Plans ....................................................................................................................................... 2-4 Short-Range Transit Plans .................................................................................................................... 2-6 3 Existing Services and Facilities ........................................................................................3-1 Fixed-Route Transit ............................................................................................................................... -

Public Transportation Modernization, Improvement, and Service Enhancement Account Program Annual Legislative Report Fiscal Year 2017–18

Public Transportation Modernization, Improvement, and Service Enhancement Account Program Annual Legislative Report Fiscal Year 2017–18 Report to the Legislature 2018 [This page intentionally left blank.] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 2 Background ................................................................................................................................ 3 Statutory Reference and Purpose ........................................................................................ 3 Program Background ........................................................................................................... 3 Program Status/Program Accomplishments ............................................................................... 4 Intercity Rail Improvement Program Projects ........................................................................ 4-10 Table 1: Open Intercity Rail Improvement Program Projects ................................................ 8 Table 2: Completed/Closed Intercity Rail Improvement Program Projects ....................... 9-10 Mass Transportation Program Proposition 1B Bond Fund .........................................................10 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................11 Appendix A. Statutory Reporting Reference .............................................................................12 -

Short Range Transit Plan

SAN LUIS OBISPO TRANSIT SHORT RANGE TRANSIT PLAN Prepared for the City of San Luis Obispo’s SLO Transit Prepared by SLO Transit Short Range Transit Plan _________________________ Prepared for the City of San Luis Obispo 919 Palm Street San Luis Obispo, CA 93401 805‐781‐7121 Prepared by LSC Transportation Consultants, Inc. 2690 Lake Forest Road, Suite C P. O. Box 5875 Tahoe City, California 96145 530 • 583‐4053 and by AECOM, Inc. August 10, 2016 LSC #157040 The document was prepared using Federal Transit Administration (FTA) discretionary funds, awarded by the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) (Sustainable Communities Program) to the San Luis Obispo Council of Governments. The recommendations and findings presented in this document are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the FTA or Caltrans. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page Executive Summary Existing Demographics ............................................................................................. ES‐1 Overview of SLO Transit ........................................................................................... ES‐1 Short Range Transit Plan Elements .......................................................................... ES‐3 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 2 Study Setting ....................................................................................................................... 3 Existing Demographics ................................................................................................. -

2006 State Transportation Improvement Program

2006 State Transportation Improvement Program Current Official STIP - (STIP funds, RIP and IIP, only) Alameda County Entire State PPNO / EA State Funds by Fiscal Year & Component (IIP & RIP Funds Only) CTIPS ID RESPONSIBLE AGENCY - PROJECT TITLE FUND PEND VOTE VOTED FUNDS PROG (Programmed Dollars in Thousands) DIST CO RTE ELEMENT LOCATION/DESCRIPTION SOURCE LAST DATE TOTAL AMOUNT 06/07 07/08 08/09 09/10 10/11 11/12 R/WCON PA&EDPS&E R/W ENG CON ENG 04 ALA 0016Q Alameda County Congestion Management Agency - AB : PM: 106-0000-0972 3090 Reimbursement Project - AB 3090 Reimbursement RIP : 07/20/06 25,037 25,037 25,037 25,037 KP: Local Assistance Project the Route 880 Widening project (PPNO 0016F) : TOTAL: 25,037 25,037 25,037 25,037 04 ALA 1014 0U8601 Bay Area Rapid Transit District - BART Transbay Tube : PM: 106-0000-0750 Seismic Retrofit - In Alameda County from the Transbay RIP : 05/02/01 10,200 48,200 38,000 38,000 10,200 KP: Rail Tube to the West Portal of the Berkeley Hills Tunnel - : seismic joints, one at-grade station and one aerial station TOTAL: 10,200 48,200 38,000 38,000 10,200 04 ALA 1022 072584 City of Oakland - 42nd Ave/High St Access to I-880 - : PM: 106-0000-0722 Oakland - 42nd Avenue/High Street access improvements to RIP : 04/13/01 1,000 6,990 5,990 5,990 1,000 KP: Local Assistance Route 880 - preliminary engineering : TOTAL: 1,000 6,990 5,990 5,990 1,000 04 ALA 2009A T161TA Alameda Contra Costa Transit District - AC Transit : PM: 0.0/ 0.0 206-0000-2155 Maintenance Facilities Upgrade - In Alameda County: AC RIP : 09/07/06 3,705 3,705 3,705 3,705 KP: 0.0/ 0.0 Mass Transit Transit District-wide facilities & equipment upgrades. -

Transit Profiles: 2014 Report Year Summary

2014 Report Year NTD National Transit Database Transit Profiles: 2014 Report Year Summary Office of Budget and Policy March 2016 Federal Transit Administration U.S. Department of Transportation Transit Profiles: 2014 Report Year Summary Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................. i Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Profile Details ............................................................................................................... 1 Sections ....................................................................................................................... 5 Additional National Transit Database Publications ....................................................... 6 Full Reporting Agencies for Report Year 2014 ................................................................ 7 Small Systems Reporting Agencies .............................................................................. 29 Separate Service Reporting Agencies........................................................................... 41 Planning Reporting Agencies ........................................................................................ 41 Building Reporting Agencies ......................................................................................... 41 Rural General Public Transit Reporting Agencies ........................................................ -

Rta Board Agenda

RTA BOARD AGENDA Wednesday, July 13, 2016 BOARD OF SUPERVISORS’ CHAMBERS COUNTY GOVERNMENT CENTER 1055 Monterey Street, San Luis Obispo, California 93401 RTA starts at 8:30 am The AGENDA is available/posted at: http://www.slorta.org President: Jan Howell Marx Vice President: Lynn Compton Board Members: Frank Mecham (First District – SLO County) Tom O’Malley (Atascadero) Bruce Gibson (Second District – SLO County) John Shoals (Grover Beach) Adam Hill (Third District – SLO County) Jamie Irons (Morro Bay) Lynn Compton (Fourth District – SLO County) Fred Strong (Paso Robles) Debbie Arnold (Fifth District – SLO County) Shelly Higginbotham (Pismo Beach) Jim Guthrie (Arroyo Grande) Jan Howell Marx (San Luis Obispo) Individuals wishing accessibility accommodations at this meeting under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) may request such accommodations to aid hearing, visual, or mobility impairment (including Limited English Proficiency [LEP]) by contacting the RTA offices at 781-4472. Please note that 48 hours advance notice will be necessary to honor a request. CALL TO ORDER AND ROLL CALL PUBLIC COMMENTS: This portion of the agenda is reserved for any members of the public to directly address the San Luis Obispo Regional Transit Authority (RTA) Board on any items not on the agenda and within the jurisdiction of the Board. Comments are limited to three minutes per speaker. The Board will listen to all communication, but in compliance with the Brown Act, will not take any action on items that are not on the agenda. A. INFORMATION AGENDA A-1 Executive Director’s Report (Receive) B. ACTION AGENDA B-1 RTA Short Range Transit Plan (Adopt) B-2 RTA Agreement with SCT for Services (Action) B-3 Receive Draft CEQA IS/MND Report for Bus Parking Facility in Paso Robles and Open 30-Day Comment Period (Action) C.