31295006292899.Pdf (13.89Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IRISH MUSIC AND HOME-RULE POLITICS, 1800-1922 By AARON C. KEEBAUGH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Aaron C. Keebaugh 2 ―I received a letter from the American Quarter Horse Association saying that I was the only member on their list who actually doesn‘t own a horse.‖—Jim Logg to Ernest the Sincere from Love Never Dies in Punxsutawney To James E. Schoenfelder 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A project such as this one could easily go on forever. That said, I wish to thank many people for their assistance and support during the four years it took to complete this dissertation. First, I thank the members of my committee—Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Paul Richards, Dr. Joyce Davis, and Dr. Jessica Harland-Jacobs—for their comments and pointers on the written draft of this work. I especially thank my committee chair, Dr. David Z. Kushner, for his guidance and friendship during my graduate studies at the University of Florida the past decade. I have learned much from the fine example he embodies as a scholar and teacher for his students in the musicology program. I also thank the University of Florida Center for European Studies and Office of Research, both of which provided funding for my travel to London to conduct research at the British Library. I owe gratitude to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for their assistance in locating some of the materials in the Victor Herbert Collection. -

January 1946) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 1-1-1946 Volume 64, Number 01 (January 1946) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 64, Number 01 (January 1946)." , (1946). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/199 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7 A . " f ft.S. &. ft. P. deed not Ucende Some Recent Additions Select Your Choruses conceit cuid.iccitzt fotidt&{ to the Catalog of Oliver Ditson Co. NOW PIANO SOLOS—SHEET MUSIC The wide variety of selections listed below, and the complete AND PUBLISHERS in the THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF COMPOSERS, AUTHORS BMI catalogue of choruses, are especially noted as compo- MYRA ADLER Grade Pr. MAUDE LAFFERTY sitions frequently used by so many nationally famous edu- payment of the performing fee. Christmas Candles .3-4 $0.40 The Ball in the Fountain 4 .40 correspondence below reaffirms its traditional stand regarding ?-3 Happy Summer Day .40 VERNON LANE cators in their Festival Events, Clinics and regular programs. BERENICE BENSON BENTLEY Mexican Poppies 3 .35 The Witching Hour .2-3 .30 CEDRIC W. -

01-Sargeant-PM

CERI OWEN Vaughan Williams’s Early Songs On Singing and Listening in Vaughan Williams’s Early Songs CERI OWEN I begin with a question not posed amid the singer narrates with ardent urgency their sound- recent and unusually liberal scholarly atten- ing and, apparently, their hearing. But precisely tion devoted to a song cycle by Ralph Vaughan who is engaged in these acts at this, the musi- Williams, the Robert Louis Stevenson settings, cal and emotional heart of the cycle? Songs of Travel, composed between 1901 and The recollected songs are first heard on the 1904.1 My question relates to “Youth and Love,” lips of the speaker in “The Vagabond,” an os- the fourth song of the cycle, in which an unex- tensibly archetypal Romantic wayfarer who in- pectedly impassioned climax erupts with pecu- troduces himself at the cycle’s opening in the liar force amid music of otherwise unparalleled lyric first-person, grimly issuing a characteris- serenity. Here, as strains of songs heard earlier tic demand for the solitary life on the open intrude into the piano’s accompaniment, the road. This lyric voice, its eye fixed squarely on the future, is retained in two subsequent songs, “Let Beauty Awake” and “The Roadside Fire” I thank Byron Adams, Daniel M. Grimley, and Julian (in which life with a beloved is contemplated).2 Johnson for their comments on this research, and espe- cially Benedict Taylor, for his invaluable editorial sugges- With “Youth and Love,” however, Vaughan tions. Thanks also to Clive Wilmer for his discussion of Williams rearranges the order of Stevenson’s Rossetti with me. -

Reception of Charles Villiers Stanford and His Music in the American Press Dr Adèle Commins, Auteur(S) Dundalk Institute of Technology, Ireland

Watchmen on the Walls of Music Across the Atlantic: Reception of Charles Villiers Stanford and his Music in the American Press Dr Adèle Commins, Auteur(s) Dundalk Institute of Technology, Ireland Titre de la revue Imaginaires (ISSN 1270-931X) 22 (2019) : « How Popular Culture Travels: Cultural Numéro Exchanges between Ireland and the United States » Pages 29-59 Directeur(s) Sylvie Mikowski et Yann Philippe du numéro DOI de l’article 10.34929/imaginaires.vi22.5 DOI du numéro 10.34929/imaginaires.vi22 Ce document est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons attribution / pas d'utilisation commerciale / pas de modification 4.0 international Éditions et presses universitaires de Reims, 2019 Bibliothèque Robert de Sorbon, Campus Croix-Rouge Avenue François-Mauriac, CS 40019, 51726 Reims Cedex www.univ-reims.fr/epure Watchmen on the Walls of Music Across the Atlantic: Reception of Charles Villiers Stanford and How PopularHow Culture Travels his Music in the American Press #22 IMAGINAIRES Dr Adèle Commins Dundalk Institute of Technology, Ireland Introduction Irish born composer Charles Villiers Stanford (1852–1924) is a cen- tral figure in the British Musical Renaissance. Often considered only in the context of his work in England, with occasional references to his Irish birthplace, the reception of Stanford’s music in America provides fresh perspectives on the composer and his music. Such a study also highlights the circulation of culture between Ireland, England and the USA at the start of the twentieth century and the importance of national identity in a cosmopolitan society of many diasporas. Although he never visited America, the reception of Stanford’s music and reviews in the American media highlight the cultural (mis)understanding that existed and the evolving identities in both American and British society at the turn of the twentieth century. -

The Kapralova Society Journal Winter 2020

Volume 18, Issue 1 The Kapralova Society Journal Winter 2020 A Journal of Women in Music Emerging from the Shadows: Maude Valérie White, a Significant Figure in the History of English Song Eugene Gates Writing in 1903, Arthur Elson reported, England before she had reached her first “Maude Valérie White takes rank among the birthday. She spent her childhood in Eng- very best of English song writers.” 1 Although land, Heidelberg and Paris, and it was she is unaccountably neglected today, probably this cosmopolitan upbringing that White played a significant role in the history awakened her lifelong interest in foreign of English vocal music. When she came to travel and nurtured her exceptional gift for the fore as a composer around 1880, the languages. She was fluent in French, Ger- English vocal scene was dominated by the man, Italian, Spanish and English, and Victorian drawing room ballad, aptly de- chose poems in those languages as texts for scribed in Grove’s Dictionary of Music and her songs. Musicians as “a composition of the slightest White’s musical education began at an degree of musical value nearly always set to early age with piano lessons from her Ger- Special points of interest: three verses (neither more nor less) of con- man governess. She loved the lessons, 6 and ventional doggerel.” 2 Through her extraordi- continued to study piano throughout her nary musical talent, and her impeccable school years with a succession of teachers. Maude Valérie White taste in literature, as reflected in the poems Although she had yet to begin the study of she chose to set, White helped to raise the music theory, she composed her first song Kaprálová: Dance for Piano artistic standard of late nineteenth-century in 1873, at the age of seventeen—a setting English song. -

Teaching Latin Love Poetry with Pop Music1

Teaching Classical Languages Volume 10, Issue 2 Kopestonsky 71 Never Out of Style: Teaching Latin Love Poetry with Pop Music1 Theodora B. Kopestonsky University of Tennessee, Knoxville ABSTRACT Students often struggle to interpret Latin poetry. To combat the confusion, teachers can turn to a modern parallel (pop music) to assist their students in understanding ancient verse. Pop music is very familiar to most students, and they already trans- late its meaning unconsciously. Building upon what students already know, teach- ers can reframe their approach to poetry in a way that is more effective. This essay shows how to present the concept of meter (dactylic hexameter and elegy) and scansion using contemporary pop music, considers the notion of the constructed persona utilizing a modern musician, Taylor Swift, and then addresses the pattern of the love affair in Latin poetry and Taylor Swift’s music. To illustrate this ap- proach to connecting ancient poetry with modern music, the lyrics and music video from one song, Taylor Swift’s Blank Space (2014), are analyzed and compared to poems by Catullus. Finally, this essay offers instructions on how to create an as- signment employing pop music as a tool to teach poetry — a comparative analysis between a modern song and Latin poetry in the original or in translation. KEY WORDS Latin poetry, pedagogy, popular music, music videos, song lyrics, Taylor Swift INTRODUCTION When I assign Roman poetry to my classes at a large research university, I re- ceive a decidedly unenthusiastic response. For many students, their experience with poetry of any sort, let alone ancient Latin verse, has been fraught with frustration, apprehension, and confusion. -

Case 17-31455 Doc 299 Filed 01/04/18

Case 17-31455 Doc 299 Filed 01/04/18 Entered 01/04/18 11:27:03 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 48 Case 17-31455 Doc 299 Filed 01/04/18 Entered 01/04/18 11:27:03 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 48 Portrait Innovations,Case Inc. 17-31455 - U.S. Mail Doc 299 Filed 01/04/18 Entered 01/04/18 11:27:03 Desc MainServed 1/3/2018 Document Page 3 of 48 11 GIRAFFES 168TH & DODGE, LLC 168TH AND DODGE, LP P.O. BOX 480100 C/O MUTUAL BANK OF OMAHA RED DEVELOPMENT CHARLOTTE, NC 28269 P.O. BOX 94133 ONE EAST WASHINGTON STREET LAS VEGAS, NV 89193-4133 SUITE 300 PHOENIX, AZ 85004 1-800-GOT-JUNK 201 HARBISON BLVD., LLC 34TH & SONCY #2, LTD DEPT. 3419 CSC ATTN: LINDA BISHOP 34TH & SONCY, LTD P.O. BOX 123419 10 BROOK STREET 5307 W. LOOP 289 DALLAS, TX 75312-3419 SUITE 205 SUITE 302 ASHVILLE, NC 28803 LUBBOCK, TX 79414 34TH & SONCY #2, LTD 34TH & SONCY #2, LTD 3503 RP WACO CENTRAL LIMITED PARTNERSHIP ATTN: KENT EWALT C/O GRACO REAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT C/O THURSTON LAW OFFICE 5307 W. LOOP 289, STE 302 PO BOX 65207 ATTN: JEFFREY EATON LUBBOCK, TX 79414 LUBBOCK, TX 79464 100 GENESEE ST., SUITE 7 AUBURN, NY 13021 8K MILES SOFTWARE SERVICES, INC. 95 NYRPT LLC 95 NYRPT, LLC 4309 HACIENDA DRIVE ATTN: KENNETH LABENSKI BENDERSON DEVELOPMENT COMPANY INC. SUITE-150 570 DELAWARE AVE 570 DELAWARE AVE. PLEASANTON, CA 94588 BUFFALO, NY, 14202 BUFFALO, NY 14202 95 NYRPT, LLC ACADEMY FIRE LIFE SAFETY, LLC. -

Song of the Year

General Field Page 1 of 15 Category 3 - Song Of The Year 015. AMAZING 031. AYO TECHNOLOGY Category 3 Seal, songwriter (Seal) N. Hills, Curtis Jackson, Timothy Song Of The Year 016. AMBITIONS Mosley & Justin Timberlake, A Songwriter(s) Award. A song is eligible if it was Rudy Roopchan, songwriter songwriters (50 Cent Featuring Justin first released or if it first achieved prominence (Sunchasers) Timberlake & Timbaland) during the Eligibility Year. (Artist names appear in parentheses.) Singles or Tracks only. 017. AMERICAN ANTHEM 032. BABY Angie Stone & Charles Tatum, 001. THE ACTRESS Gene Scheer, songwriter (Norah Jones) songwriters; Curtis Mayfield & K. Tiffany Petrossi, songwriter (Tiffany 018. AMNESIA Norton, songwriters (Angie Stone Petrossi) Brian Lapin, Mozella & Shelly Peiken, Featuring Betty Wright) 002. AFTER HOURS songwriters (Mozella) Dennis Bell, Julia Garrison, Kim 019. AND THE RAIN 033. BACK IN JUNE José Promis, songwriter (José Promis) Outerbridge & Victor Sanchez, Buck Aaron Thomas & Gary Wayne songwriters (Infinite Embrace Zaiontz, songwriters (Jokers Wild 034. BACK IN YOUR HEAD Featuring Casey Benjamin) Band) Sara Quin & Tegan Quin, songwriters (Tegan And Sara) 003. AFTER YOU 020. ANDUHYAUN Dick Wagner, songwriter (Wensday) Jimmy Lee Young, songwriter (Jimmy 035. BARTENDER Akon Thiam & T-Pain, songwriters 004. AGAIN & AGAIN Lee Young) (T-Pain Featuring Akon) Inara George & Greg Kurstin, 021. ANGEL songwriters (The Bird And The Bee) Chris Cartier, songwriter (Chris 036. BE GOOD OR BE GONE Fionn Regan, songwriter (Fionn 005. AIN'T NO TIME Cartier) Regan) Grace Potter, songwriter (Grace Potter 022. ANGEL & The Nocturnals) Chaka Khan & James Q. Wright, 037. BE GOOD TO ME Kara DioGuardi, Niclas Molinder & 006. -

Performing National Identity During the English Musical Renaissance in A

Making an English Voice: Performing National Identity during the English Musical Renaissance In a 1925 article for Music & Letters entitled ‘On the Composition of English Songs’, the British musicologist Edward J. Dent urged the ‘modern English composer’ to turn serious attention to the development of ‘a real technique of song-writing’.1 As Dent underlined, ‘song-writing affects the whole style of English musical composition’, for we English are by natural temperament singers rather than instrumentalists […] If there is an English style in music it is founded firmly on vocal principles, and, indeed, I have heard Continental observers remark that our whole system of training composers is conspicuously vocal as compared with that of other countries. The man who was born with a fiddle under his chin, so conspicuous in the music of Central and Eastern Europe, hardly exists for us. Our instinct, like that of the Italians, is to sing.2 Yet, as he quickly qualified: ‘not to sing like the Italians, for climactic conditions have given us a different type of language and apparently a different type of larynx’.3 1 I am grateful to Byron Adams, Daniel M. Grimley, Alain Frogley, and Laura Tunbridge for their comments on this research. E. J. Dent, ‘On the Composition of English Songs’, Music & Letters, 6.3 (July, 1925). 2 Dent, ‘On the Composition of English Songs’, 225. 3 Dent, ‘On the Composition of English Songs’, 225. 1 With this in mind, Dent outlined a ‘style of true English singing’ to which the English song composer might turn for his ‘primary inspiration’: a voice determined essentially by ‘the rhythms and the pace of ideal English speech – that is, of poetry’, but also, a voice that told of the instinctive ‘English temperament’. -

(Iowa City, Iowa), 1948-02-14

lbCal - Team to Indiana; Lincoln. Train ~ THE WEATHER TODAY Cold wave to day and tonight. Snow flurries and strong shifting winds today diminishing to Hawks Invade Indiana night. Tomorrow partly cloudy and quite cold . High near 30. Low zero to 5 below. low yester .In rry for Loop Top at owa11. day in Iowa City, 14. By BUCK TURNBULL .. .. F.tabliahed 18GS-Vol 80, No. 118-AP News and Wirephoto Iowa Clty, Iowa, Saturday, rebruary 14, 1948-Five Cents ports Edltor . BLOOMINGTON, Ind. (JP) The Lincoln Train 4. Indiana basketball learn stands between Iowa and lhe Big Nine Small Boy - But· a Big Operator leaderShip as the two learns Senate Group Agrees ~uare off here in the Hoosier Slops In Ie lieldhouse tonigh L 'l'he Hawkeye quintet, riding the crest of thl'ee straight confer enl'l! wins nnd a six won-two lost Enroule Easl European Bill league record, can move ahead of On Aid Wisconsin's idle Badgers with a. The Rock Island section of the "Iclory over l ndians. Wisconsin Abraham Lincoln Friendship train WASHINGTON (IP)-Aid to and Iowa are currently tied for pulled into Iowa City at 7:37 yes * * * Europe received a shot in the arm the Big Nine top. terday morning, paused briefly for yesterday. Late in the afternoon the press and co ntinued on Its The Hawks c'.~ealed Indiana Upholds Union a Senate foreign relations commit mission. earlier III the season al Iowa City, Twenty-eight cars of wheat and , tee agreed on a four-year Europe 61 -52. an recovery program. -

Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Masters Applied Arts 2018 Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930. David Scott Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appamas Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Scott, D. (2018) Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930.. Masters thesis, DIT, 2018. This Theses, Masters is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900–1930 David Scott, B.Mus. Thesis submitted for the award of M.Phil. to the Dublin Institute of Technology College of Arts and Tourism Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama February 2018 i ABSTRACT Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, arrangements of Irish airs were popularly performed in Victorian drawing rooms and concert venues in both London and Dublin, the most notable publications being Thomas Moore’s collections of Irish Melodies with harmonisations by John Stephenson. Performances of Irish ballads remained popular with English audiences but the publication of Stanford’s song collection An Irish Idyll in Six Miniatures in 1901 by Boosey and Hawkes in London marks a shift to a different type of Irish song. -

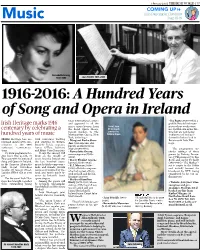

1916-2016: a Hundred Years of Song and Opera in Ireland

6 February 2016 | THE IRISH WORLD | 17 COMING UP8 Music Irish Dancing in Cheshunt Page 18-19 Bernadette Greevy 1940-2008 Joan Trimble 1915-2000 1916-2016: A Hundred Years of Song and Opera in Ireland huge international careers • Ina Boyle (1889-1967), a Irish Heritage marks 1916 and appeared in all the prolific female Irish com- major opera houses, from Count John poser whose works were centenary by celebrating a the Royal Opera House, McCormack not well-known in her life- Covent Garden, to The painted by time but are now being hundred years of music Metropolitan Opera, New William Orpen “rediscovered” and per- York, including:- formed in Ireland and in IRISH Heritage has an- Irish musicians working • Margaret Burke Sheri- Britain with Irish Her- nounced details of its con- and studying in Britain, dan, lyric soprano, also itage. tribution to the 1916 Jennifer Davis, soprano, known as Maggie from centenary commemora- Aaron O’Hare, baritone Mayo (1889-1958) The programme in- tions. and Máire Carroll on piano. • Bernadette Greevy, cludes settings of three Its 2016 programme be- It says the concert will mezzo-soprano (1940- poems by Padraig Pearse: gins later this month, 17 draw on the wealth of 2008) two [UK premiers] by Ina February, with A Century of music heard in Ireland over • Harry Plunket Greene, Boyle and one by TC Kelly Song and Opera in Ireland, the last hundred years: baritone (1865-1936) (1917-1985) - The Mother - in the Princess Alexandra music by Irish composers – • E.J. Moeran (1894- set to music in the 1960s Hall, Royal Over-Seas male and female; British 1950) a British composer and initially banned for League, St James’s Street, composers inspired by Ire- who had a great affinity broadcast by RTE, being London SW1A 1LR at 7.30 land, and music made fa- with Ireland and died in considered to be too in- pm.