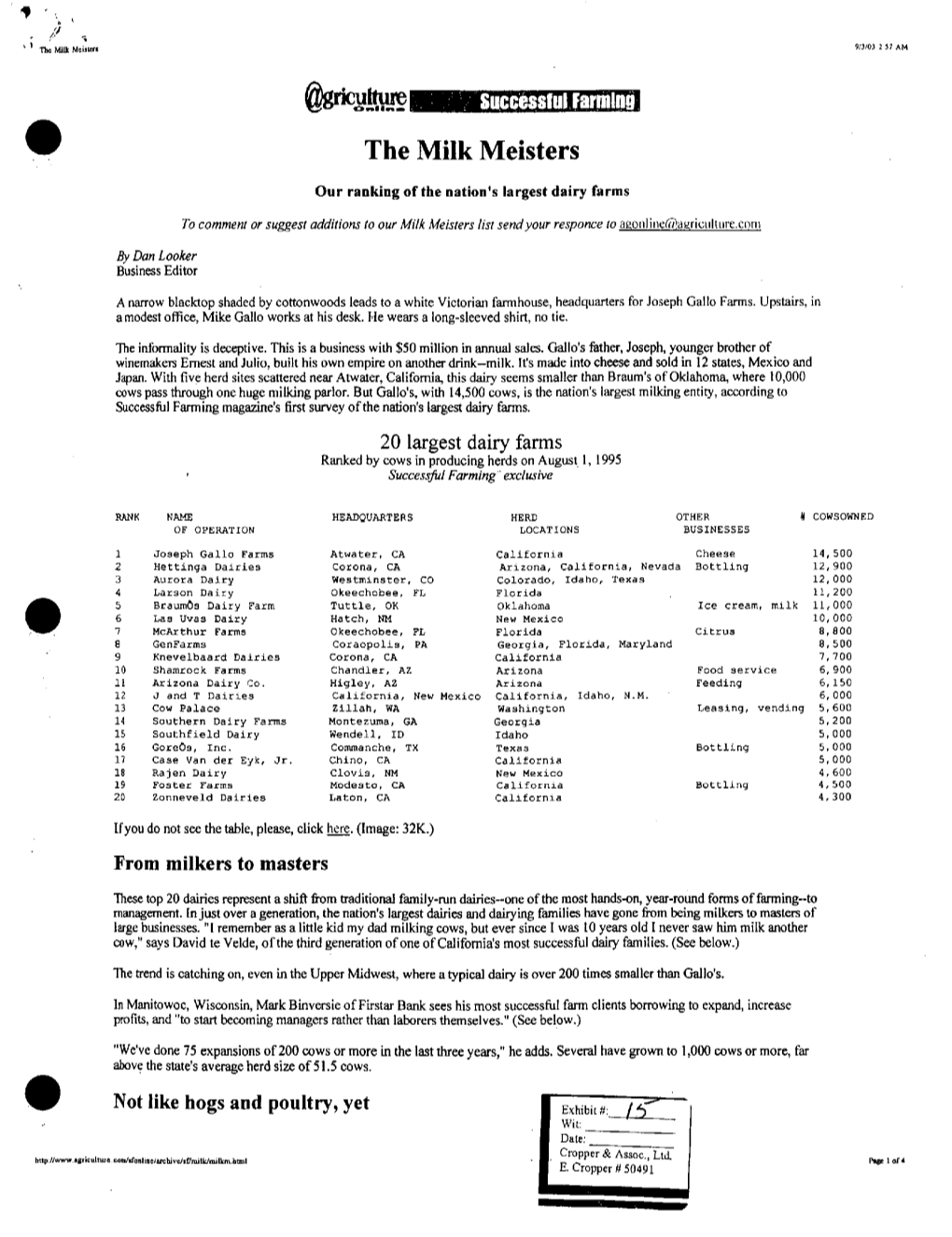

The Milk Meisters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sysco Cheese Product Catalog

> the Sysco Cheese Product Catalog Sysco_Cheese_Cat.indd 1 7/27/12 10:55 AM 5 what’s inside! 4 More Cheese, Please! Sysco Cheese Brands 6 Cheese Trends and Facts Creamy and delicious, 8 Building Blocks... cheese fi ts in with meal of Natural Cheese segments during any Blocks and Shreds time of day – breakfast, Smoked Bacon & Cheddar Twice- Baked Potatoes brunch, lunch, hors d’oeuvres, dinner and 10 Natural Cheese from dessert. From a simple Mild to Sharp Cheddar, Monterey Jack garnish to the basis of and Swiss a rich sauce, cheese is an essential ingredient 9 10 12 A Guide to Great Italian Cheeses Soft, Semi-Soft and for many food service Hard Italian Cheeses operations. 14 Mozzarella... The Quintessential Italian Cheese Slices, shreds, loaves Harvest Vegetable French and wheels… with Bread Pizza such a multitude of 16 Cream Cheese Dreams culinary applications, 15 16 Flavors, Forms and Sizes the wide selection Blueberry Stuff ed French Toast of cheeses at Sysco 20 The Number One Cheese will provide endless on Burgers opportunities for Process Cheese Slices and Loaves menu innovation Stuff ed Burgers and increased 24 Hispanic-Style Cheeses perceived value. Queso Seguro, Special Melt and 20 Nacho Blend Easy Cheese Dip 25 What is Speciality Cheese? Brie, Muenster, Havarti and Fontina Baked Brie with Pecans 28 Firm/Hard Speciality Cheese Gruyère and Gouda 28 Gourmet White Mac & Cheese 30 Fresh and Blue Cheeses Feta, Goat Cheese, Blue Cheese and Gorgonzola Portofi no Salad with 2 Thyme Vinaigrette Sysco_Cheese_Cat.indd 2 7/27/12 10:56 AM welcome. -

Use of Iodised Salt in Cheese Manufacturing to Improve Iodine Status in the UK

Use of iodised salt in cheese manufacturing to improve iodine status in the UK by Suruchi Pradhan A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire November/2019 1 STUDENT DECLARATION FORM Type of Award Doctor of Philosophy in Nutrition School School of Sports and Health Sciences Sections marked * delete as appropriate 1. Concurrent registration for two or more academic awards *I declare that while registered as a candidate for the research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution 2. Material submitted for another award *I declare that no material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work. Signature of Candidate ______ ________________________________________________ Print name: Suruchi Pradhan ____________________________________________________________ 2 Abstract Iodine is an essential trace mineral. Iodine deficiency during pregnancy can lead to adverse postnatal consequences such as impaired mental development, reduced intelligence scores and impaired motor skills in the offspring of the deficient women (Khazan et al., 2013, Rayman et al, 2008). There is growing evidence in the UK of low dietary iodine intakes and potential iodine deficiency in vulnerable populations (pregnant women and women of child bearing age group) (Rayman and Bath, 2015, Vanderpump et al., 2011) and a paucity of information on the iodine content of food products. In developing countries where iodine deficiency is widespread, salt has successfully been used as a vehicle for iodine fortification, however iodised salt is not widely available in UK supermarkets and there are valid health concerns about promoting salt intake. -

A Guide to Kowalski's Specialty Cheese Read

Compliments of Kowalski’s WWW.KOWALSKIS.COM A GUIDE TO ’ LOCALOUR FAVORITE CHEESES UNDERSTANDING CHEESE TYPES ENTERTAINING WITH CHEESE CHEESE CULTURES OF THE WORLD A PUBLICATION WRITTEN AND PRODUCED BY KOWALSKI’S MARKETS Printed November 2015 SPECIALTY CHEESE EXPERIENCE or many people, Kowalski’s Specialty Cheese Department Sadly, this guide could never be an all-inclusive reference. is their entrée into the world of both cheese and Kowalski’s Clearly there are cheese types and cheesemakers we haven’t Fitself. Many a regular shopper began by exclusively shopping mentioned. Without a doubt, as soon as this guide goes to this department. It’s a tiny little microcosm of the full print, our cheese selection will have changed. We’re certainly Kowalski’s experience, illustrating oh so well our company’s playing favorites. This is because our cheese departments are passion for foods of exceptional character and class. personal – there is an actual person in charge of them, one Cheese Specialist for each and every one of our 10 markets. When it comes to cheese, we pay particular attention Not only do these specialists have their own faves, but so do to cheeses of unique personality and incredible quality, their customers, which is why no two cheese sections look cheeses that are perhaps more rare or have uncommon exactly the same. But though this special publication isn’t features and special tastes. We love cheese, especially local all-encompassing, it should serve as an excellent tool for cheeses, artisanal cheeses and limited-availability treasures. helping you explore the world of cheese, increasing your appreciation and enjoyment of specialty cheese and of that Kowalski’s experience, too. -

DAIRY at the HIGHEST LEVEL on the Economic Importance and Quality of the Dutch Dairy Sector Summary

DAIRY AT THE HIGHEST LEVEL On the economic importance and quality of the Dutch dairy sector Summary Quality and cooperation The Dutch dairy sector largely owes its strong global market position to high, consistent quality and a capacity for innovation. From our world-famous Gouda and Edam cheeses to milk powder and high-quality ingredients: dairy from the Netherlands is synonymous with the highest quality. This quality is the result of Dutch dairy farmers’ and producers’ years of experience and craftsmanship, as well as close cooperation with knowledge institutes and the government. Take a look behind the scenes of a high-quality food industry with a unique quality system. 2 Dairy at the highest level Dairy at the highest level 3 Foreword/Contents Dutch dairy at the highest level We never really talk about quality. We simply take continuously working on improving the quality of euros in turnover. This is a stable industry, which is for granted the fact that our products are in order our products, and safeguarding our processes and deeply rooted in Dutch society. That makes the every day. That’s simply a precondition. Consumers making them more sustainable. We all do this dairy sector robust. Precisely because of this we can must be able to trust that every Dutch dairy together. Not only dairy companies united in the handle crises, such as the coronavirus, trade wars or product is safe. They should also know that every Dutch Dairy Association (Nederlandse Zuivel fi nancial turmoil. The ongoing attention we pay to piece of cheese or packet of yogurt will have the Organisatie, NZO), but also dairy farmers, the the quality of our products and our production same familiar taste, time after time. -

Ripening of Hard Cheese Produced from Milk Concentrated by Reverse Osmosis

foods Article Ripening of Hard Cheese Produced from Milk Concentrated by Reverse Osmosis Anastassia Taivosalo 1,2,*, Tiina Krišˇciunaite 1, Irina Stulova 1, Natalja Part 1, Julia Rosend 1,2 , Aavo Sõrmus 1 and Raivo Vilu 1,2 1 Center of Food and Fermentation Technologies, Akadeemia tee 15A, 12618 Tallinn, Estonia; [email protected] (T.K.); [email protected] (I.S.); [email protected] (N.P.); [email protected] (J.R.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (R.V.) 2 Department of Chemistry and Biotechnology, Tallinn University of Technology, Akadeemia tee 15, 12618 Tallinn, Estonia * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 April 2019; Accepted: 13 May 2019; Published: 15 May 2019 Abstract: The application of reverse osmosis (RO) for preconcentration of milk (RO-milk) on farms can decrease the overall transportation costs of milk, increase the capacity of cheese production, and may be highly attractive from the cheese manufacturer’s viewpoint. In this study, an attempt was made to produce a hard cheese from RO-milk with a concentration factor of 1.9 (RO-cheese). Proteolysis, volatile profiles, and sensory properties were evaluated throughout six months of RO-cheese ripening. Moderate primary proteolysis took place during RO-cheese ripening: about 70% of αs1-casein and 45% of β-casein were hydrolyzed by the end of cheese maturation. The total content of free amino 1 acids (FAA) increased from 4.3 to 149.9 mmol kg− , with Lys, Pro, Glu, Leu, and γ-aminobutyric acid dominating in ripened cheese. In total, 42 volatile compounds were identified at different stages of maturation of RO-cheese; these compounds have previously been found in traditional Gouda-type and hard-type cheeses of prolonged maturation. -

Fall 2006 Handcrafted Cheese: a Living, Breathing Tradition

VOLUMEVOLUME XVI, XXII, NUMBER NUMBER 4 4 FALL FALL 2000 2006 Quarterly Publication of the Culinary Historians of Ann Arbor Preserving the Art of Handmade Cheeses Chris Owen sprinkles herbs on fresh rounds of cheese, which she made from the milk of her own herd of goats in the Appalachian hill country of North Carolina. Chris tells us about her Spinning Spider Creamery starting on page 5. REPAST VOLUME XXII, NUMBER 4 FALL 2006 HANDCRAFTED CHEESE: A LIVING, BREATHING TRADITION Once, at the dinner table when we were about to have dessert, Chicago, who in 1916 patented a way to multiply the shelf life of my grandfather Joseph Carp asked for a wedge of cheddar cheese cheese by killing off all of its microbial life. The resulting alongside his slice of apple pie, which was a combination I’d never “processed cheese food” was a windfall for Kraft, for it was stable heard of before. I was a boy growing up in suburban Virginia, and enough to be rationed out to U.S. soldiers fighting overseas during my mother’s parents were visiting with us. The commercial-brand World War 1. The rest is history. cheddar that my Mom cut for Grandpa Joe was a favorite of mine, but it became clear that it wasn’t quite up to his highest standards. Or perhaps just one chapter of it. Today, in many different When he asked to see the package in which it had been wrapped, ways and in many different places around the world, food he noted with more than a hint of disapproval that the cheese had traditionalists are making a strong stand against industrial been made from pasteurized milk. -

Abstract Ameerally, Angelique

ABSTRACT AMEERALLY, ANGELIQUE DANIELLE. Sensory and Chemical Properties of Gouda Cheese. (Under the direction of MaryAnne Drake). Gouda cheese (G) is a Dutch, washed curd cheese that is traditionally produced from bovine milk and brined before ripening for 1-20 months. In response to domestic and international demand, U.S. production of Gouda cheese has more than doubled in recent years. An understanding of the chemical and sensory properties of G can help manufacturers to create desirable products. The objective of this study was to determine the chemical and sensory properties of Gouda cheeses. Commercial Gouda cheeses (n=36, 3 mo to 5 y, domestic and international) were obtained in duplicate lots. Volatile compounds were extracted (SPME) and analyzed by gas chromatography olfactometry (GCO) and gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GCMS). Physical analyses included pH, proximate analysis, salt content, organic acid analysis by HPLC, and color. Flavor and texture properties were determined by descriptive sensory analysis. Focus groups were conducted with cheese followed by consumer acceptance testing (n=153) with selected cheeses. Ninety aroma active compounds were detected in cheeses by SPME- GC-O. Key volatile compounds in Gouda cheeses included dimethyl sulfide, 2,3- butanedione, 2/3-methylbutanal, ethyl butyrate, acetic acid, and methional. Older cheeses had higher organic acid concentrations, higher fat and salt content, and lower moisture content than younger G. Younger cheeses were characterized by milky, whey, sour aromatic, and diacetyl flavors while older G were characterized by fruity, caramel, malty/nutty, and brothy flavors. International cheeses were differentiated by the presence of low intensities of cowy/barny and grassy flavors. -

Delores B. Phillips, Doctor of Philosophy, 2009 Professor

ABSTRACT Title: IN QUESTIONABLE TASTE: EATING CULTURE, COOKING CULTURE IN ANGLOPHONE POSTCOLONIAL TEXTS Delores B. Phillips, Doctor of Philosophy, 2009 Dissertation Directed by: Professor Sangeeta Ray, Department of English Language and Literature This dissertation produces an extensive and intensive study of the culture of food in postcolonial literature and cookbooks that describe particular regions and cultures. It treats novels and cookbooks that depict food and eating in Africa, South Asia, and the Caribbean to argue that while both cookbooks and novels depict as unstable the connection between food and culture; the key difference lies in the manner in which each genre describes that instability. The study uses memoir cookbooks (cookbooks that use the autobiographical accounts of their authors as a method of organizing content and providing context for recipes) and literary depictions of cooking and eating to trouble the neat tautology that establishes food and home as interchangeable cultural signifiers of equal weight. It evaluates the work that cookbooks do by comparing them to representations of cooking, eating and food in representative novels that frame depictions of citizenship and the nation in deeply ambivalent terms even as they depict delicious meals, well- laid family tables, and clean, productive kitchens. The dissertation studies cookbooks and novels to illustrate how the text under consideration act out the concerns that structure postcolonial critique. If regional cookbooks provide obscured or incomplete insight into the cultures they purport to authentically depict, then the novels under study provide openly ambivalent accounts of cultural identification. The study begins by examining how pan-cultural cookbooks do the work of drawing multiple nations beneath the aegis of the global—and how this work fails to engage the problematic cosmopolitics of globality as revealed in two South Asian novels. -

Varieties of Cheese

Research Library Bulletins 4000 - Research Publications 1980 Varieties of cheese T A. Morris Follow this and additional works at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/bulletins Part of the Dairy Science Commons, and the Food Processing Commons Recommended Citation Morris, T A. (1980), Varieties of cheese. Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Western Australia, Perth. Bulletin 4066. This bulletin is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Publications at Research Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletins 4000 - by an authorized administrator of Research Library. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CA1 Department of Agriculture, Western Australia. BULLETIN 4066 AGDEX 416/80 Varieties of cheese by T. A. Morris Chief, Division of Dairying and Food Technology VARIETIES OF CHEESE by T. A. Morris Chief, Division of Dairying and Food Technology While Cheddar cheese is by far the main type as far RIPENED CHEESE English speaking countries concerned, it is only as are Cheese ripened by bacteria one of a large number of varieties of cheese which are becoming more universal in production and con- This group includes those cheeses in which most of sumption. In other than English speaking countries the ripening and flavour development is a result of the Cheddar cheese is almost unknown and yet the con- action of bacteria within the cheese. In considering sumption of cheese in some of these countries is very these cheeses it is found that they can be formed into much greater. two sub-groups on the basis of the presence or absence of round holes known as "eyes" in the cheese. -

Reference Manual for U.S. Cheese

Reference Manual for U.S. Cheese CONTENTS Introduction U.S. Cheese Selection Acknowledgements ................................................................................. 5 5.1 Soft-Fresh Cheeses ........................................................................53 U.S. Dairy Export Council (USDEC) ..................................................... 5 5.2 Soft-Ripened Cheeses ..................................................................58 5.3 Semi-Soft Cheeses ....................................................................... 60 The U.S. Dairy Industry and Export Initiatives 5.4 Blue-Veined Cheeses ................................................................... 66 1.1 Overview of the U.S. Dairy Industry ...........................................8 5.5 Gouda and Edam ........................................................................... 68 1.2 Cooperatives Working Together (CWT) ................................. 10 5.6 Pasta Filata Cheeses ..................................................................... 70 The U.S. Cheese Industry 5.7 Cheeses for Pizza and Blends .....................................................75 5.8 Cheddar and Colby ........................................................................76 2.1 Overview ............................................................................................12 5.9 Swiss Cheeses .................................................................................79 2.2 Safety of U.S. Cheese and Dairy Products ...............................15 5.10 -

(Carica Papaya) PROTEASE in CREAM CHEESE PREPARATION by RESPONSE SURFACE METHODOLOGY

OPTIMIZATION OF CRUDE PAPAYA (Carica papaya) PROTEASE IN CREAM CHEESE PREPARATION BY RESPONSE SURFACE METHODOLOGY by Nabindra Kumar Shrestha Department of Food Technology Central Campus of Technology Institute of Science and Technology Tribhuvan University, Nepal 2019 Optimization of Crude Papaya (Carica papaya) Protease in Cream Cheese Preparation by Response Surface Methodology A dissertation submitted to the Department of Food Technology, Central Campus of technology, Tribhuvan University, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of B. Tech. in Food Technology by Nabindra Kumar Shrestha Department of Food Technology Central Campus of Technology Institute of Science and Technology Tribhuvan University, Nepal May, 2019 ii Tribhuvan University Institute of Science and Technology Department of Food Technology Central Campus of Technology, Dharan Approval Letter This dissertation entitled Optimization of Crude Papaya (Carica papaya) Protease in Cream Cheese Preparation by Response Surface Methodology presented by Nabindra Kumar Shrestha has been accepted as the partial fulfilment of the requirement for the B. Tech. degree in Food Technology. Dissertation Committee 1. Head of Department ___________________________________________ (Mr. Basanta Kumar Rai, Assoc. Prof.) 2. External Examiner ___________________________________________ (Mr. Shyam Kumar Mishra, Assoc. Prof.) 3. Supervisor ___________________________________________ (Mr. Bunty Maskey, Asst. Prof.) 4. Internal Examiner ___________________________________________ (Mr. Yadav K.C., Asst. Prof.) Co-supervisor ___________________________________________ (Mr. Ram Shovit Yadav, Asst. Prof.) May, 2019 iii Acknowledgements I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my respected guide Asst. Prof. Mr. Bunty Maskey for his kind support, excellent guidance, encouragement and constructive recommendations throughout the work. I am really thankful to Prof. Dr. Dhan Bahadur Karki (Campus Chief, Central Campus of Technology) and Assoc. -

Dairy Quick Scan Sudan the Netherlands, October 2016

Report for: Rijksdienst voor Ondernemend Nederland Dairy quick scan Sudan The Netherlands, October 2016 THE FRIESIAN FOTO 1 The Friesian – Dairy Development Company Table of content Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Country profile ................................................................................................................................................. 8 2.1 Land features .......................................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Demographics ....................................................................................................................................... 11 2.3 Eastern Sudan ....................................................................................................................................... 11 2.4 Economics ............................................................................................................................................. 12 3. Dairy sector in Sudan ..................................................................................................................................... 13 3.1 General facts ........................................................................................................................................