Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partnership Against Transnational Crime Through Regional Organized Law Enforcement” (“PATROL”) Project, Led by UNODC

Partnership against Transnational Crime through Regional Organized Law Enforcement (PATROL) Project Number: XAP/U59 Baseline survey and training needs assessment in Myanmar © United Nations Environment Programme 17-21 October 2011 DISCLAIMER: The results from the survey reflect the perception of participants, and they are not the results of specific investigations by UNODC or PATROL partners - Freeland Foundation, TRAFFIC and UNEP. Any error in the interpretation of these results cannot be directly attributed to an official position of any of the organizations involved. 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Background and Context – The PATROL Project...................................................... 4 1.2. Objective of the Baseline Survey and TNA................................................................ 4 2. Methodology ......................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. Basic Statistics of the Sample ..................................................................................... 5 2.2. Limitations of the Methodology.................................................................................. 6 3. Major Findings ..................................................................................................................... 7 3.1. Survey Findings.......................................................................................................... -

Covid-19 Response Situation Report 3 | 1 May 2020

IOM MYANMAR COVID-19 RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT 3 | 1 MAY 2020 2,500 migrant per day to be allowed to return through the Myawaddy-Mae Sot border gate 16,324 migrants registered online in preparation to return through the Myawaddy-Mae Sot border gate 3,125 international migrants returned to Kachin State mainly from the People’s Republic of China Migrants preparing to return to their communities of origin following 21 days of quarantine at Myawaddy, Kayin State. © IOM 2020 SITUATION OVERVIEW The border with Thailand was expected to re-open on 1 May of China and through the Lweje border gate, according to data to allow a second large influx of migrants (estimated 20,000 from the Kachin State Government (695 internal migrants also to 50,000 returns). The Myanmar Government requested to returned from other states and regions of Myanmar). the Thai Government to only allow 2,500 returnees per day Returnees are being transported to Myitkyina, and from there, through the Myawaddy border gate; however, due to the to their communities of origin where they will stay in extension of the Emergency Decree in Thailand until 31 May, community-based facility quarantine centres. returns are delayed for a few more days to allow for the necessary arrangements to be put in place by Thai authorities. Government Ministries and Departments, the State Government, UN agencies and other actors supporting the COVID-19 response are closely observing the situation in order to quickly respond to potential large scale returns in the coming days. It is expected that approximately 2,000 returning migrants will be quarantined in Myawaddy, while the remainder will be transported from the border to their home communities for community-based quarantine. -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

Grave Diggers a Report on Mining in Burma

GRAVE DIGGERS A REPORT ON MINING IN BURMA BY ROGER MOODY CONTENTS Abbreviations........................................................................................... 2 Map of Southeast Asia............................................................................. 3 Acknowledgments ................................................................................... 4 Author’s foreword ................................................................................... 5 Chapter One: Burma’s Mining at the Crossroads ................................... 7 Chapter Two: Summary Evaluation of Mining Companies in Burma .... 23 Chapter Three: Index of Mining Corporations ....................................... 29 Chapter Four: The Man with the Golden Arm ....................................... 43 Appendix I: The Problems with Copper.................................................. 53 Appendix II: Stripping Rubyland ............................................................. 59 Appendix III: HIV/AIDS, Heroin and Mining in Burma ........................... 61 Appendix IV: Interview with a former mining engineer ........................ 63 Appendix V: Observations from discussions with Burmese miners ....... 67 Endnotes .................................................................................................. 68 Cover: Workers at Hpakant Gem Mine, Kachin State (Photo: Burma Centrum Nederland) A Report on Mining in Burma — 1 Abbreviations ASE – Alberta Stock Exchange DGSE - Department of Geological Survey and Mineral Exploration (Burma) -

Financial Inclusion

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 I LIFT Annual Report 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 II III LIFT Annual Report 2020 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank LBVD Livestock Breeding and Veterinary ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Department CBO Community-based Organisation We thank the governments of Australia, Canada, the European Union, LEARN Leveraging Essential Nutrition Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and CSO Civil Society Organisation Actions To Reduce Malnutrition project the United States of America for their kind contributions to improving the livelihoods and food security of rural poor people in Myanmar. Their DAR Department of Agricultural MAM Moderate acute malnutrition support to the Livelihoods and Food Security Fund (LIFT) is gratefully Research acknowledged. M&E Monitoring and evaluation DC Donor Consortium MADB Myanmar Agriculture Department of Agriculture Development Bank DISCLAIMER DoA DoF Department of Fisheries MEAL Monitoring, evaluation, This document is based on information from projects funded by LIFT in accountability and learning 2020 and supported with financial assistance from Australia, Canada, the DRD Department for Rural European Union, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the United Development MoALI Ministry of Agriculture, Kingdom, and the United States of America. The views expressed herein Livestock and Irrigation should not be taken to reflect the official opinion of the LIFT donors. DSW Department of Social Welfare MoE Ministry of Education Exchange rate: This report converts MMK into -

Challenging Myanmar's Centralized Energy Model

ETHNIC NATIONALITIES AFFAIRS CENTER CHALLENGING MYANMAR’S CENTRALIZED ENERGY MODEL ETHNIC NATIONALITIES AFFAIRS CENTER (UNION OF BURMA) P.O. Box 5, Chang Puak, A. Mueang Chiang Mai 50302, Thailand www.burmaenac.org Challenging Myanmar’s Centralized Energy Model 1 Printing Information First Edition: July 2020 Copies: 1,000 Distributor: Ethnic Nationalities Affairs Center (Union of Burma) Photo: ENAC Design: Ying Tzarm Address: P.O Box 5, Chang Peauk, A.Mueang Chiang Mai 50302, Thailand ETHNIC NATIONALITIES AFFAIRS CENTER CHALLENGING MYANMAR’S CENTRALIZED ENERGY MODEL JULY 2020 CONTENTS Page Foreword 1 Acronyms 3 Executive Summary 5 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 1.1 Structure of the Paper 10 1.2 Research Methodology 10 1.3 Myanmar Energy and Power Overview 11 1.3.1 Crude Oil 12 1.3.2 Natural Gas and Power Plant Development 14 1.3.3 Coal Deposits and Power Plant Development 20 1.3.4 Solar and Wind Power Plant Development 21 1.3.5 Existing Hydropower Plants in the States/Regions 23 1.3.6 Overview of National Electrification 28 1.3.7 Energy/Power Development Projects and Conflict 37 Chapter 2: The Role of the State/Regional Governments in Power/Energy Sector 41 2.1 Energy Executive Body of the State/Regional Governments 41 2.2 Energy Related Taxation Authority of the State/Regional and Union Governments 49 2.3 Energy-related Legislative Authority of the State/Regional Governments 52 2.4 The Role of State/Regional Governments in Energy Investment Sector 52 2.5 Procedure for Environmental Impact Assessment or an Initial Environmental Examination -

THE STATE of LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS in KACHIN Photo Credits

Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN KACHIN Photo credits Mike Adair Emilie Röell Myanmar Survey Research A photo record of the UNDP Governance Mapping Trip for Kachin State. Travel to Tanai, Putao, Momauk and Myitkyina townships from Jan 6 to Jan 23, 2015 is available here: http://tinyurl.com/Kachin-Trip-2015 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP. Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN KACHIN UNDP MYANMAR Table of Contents Acknowledgements II Acronyms III Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 5 2. Kachin State 7 2.1 Kachin geography 9 2.2 Population distribution 10 2.3 Socio-economic dimensions 11 2.4 Some historical perspectives 13 2.5 Current security situation 18 2.6 State institutions 18 3. Methodology 24 3.1 Objectives of mapping 25 3.2 Mapping tools 25 3.3 Selected townships in Kachin 26 4. Governance at the front line – Findings on participation, responsiveness and accountability for service provision 27 4.1 Introduction to the townships 28 4.1.1 Overarching development priorities 33 4.1.2 Safety and security perceptions 34 4.1.3 Citizens’ views on overall improvements 36 4.1.4 Service Provider’s and people’s views on improvements and challenges in selected basic services 37 4.1.5 Issues pertaining to access services 54 4.2 Development planning and participation 57 4.2.1 Development committees 58 4.2.2 Planning and use of development funds 61 4.2.3 Challenges to township planning and participatory development 65 4.3 Information, transparency and accountability 67 4.3.1 Information at township level 67 4.3.2 TDSCs and TMACs as accountability mechanisms 69 4.3.3 WA/VTAs and W/VTSDCs 70 4.3.4 Grievances and disputes 75 4.3.5 Citizens’ awareness and freedom to express 78 4.3.6 Role of civil society organisations 81 5. -

Covid-19 Response Situation Report 2 | 23 April 2020

IOM MYANMAR COVID-19 RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT 2 | 23 APRIL 2020 60,363 Myanmar returnees returned to Myanmar 2,623 returns to Kachin mainly from China 6,808 quarantine facilities nationwide 21 days of quarantine required for migrants upon arrival Migrants at an unofficial border crossing near Myawaddy, Kayin State. © IOM 2020/Lynn Phyo MAUNG SITUATION OVERVIEW As of 23 April, as based on available data, a total of 60,363 There has been a large-scale influx of returnees to Kachin migrants had returned to Myanmar, with the number of State, mainly from China, with an estimated 2,623 people official returns remaining very low due to the closure of the having returned through Lweje so far according to data from border, and with only a small number of returns permitted the Department of Labour. They are being transported to through the Three Pagodas Pass checkpoint. Myitkyina and from there, to their communities of origin where they will be quarantined. The total number of migrants expected to return to Myanmar from China is between 10,000- 18,000 by late April. Migrants face several challenges upon arrival, including being required to quarantine for 21 days upon arrival, with most migrants primarily requested to quarantine in community- based quarantine facilities (mainly schools and monasteries). However, due to insufficient capacity, the majority of returnees have been practicing home-quarantining. A total of 6,808 quarantine facilities have been set-up nationwide. UN CORE GROUP ON RETURNING MIGRANTS IOM is coordinating the response of the United Nations to the IOM partner, Chin Human Rights Organization (CHRO), supporting the Falam Township COVID-19 Committee to install a community hand-washing station situation of returning migrants in Myanmar through the UN near Falam, Chin State. -

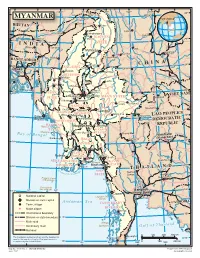

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

Kahrl Navigating the Border Final

CHINA AND FOREST TRADE IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGION: IMPLICATIONS FOR FORESTS AND LIVELIHOODS NAVIGATING THE BORDER: AN ANALYSIS OF THE CHINA- MYANMAR TIMBER TRADE Fredrich Kahrl Horst Weyerhaeuser Su Yufang FO RE ST FO RE ST TR E ND S TR E ND S COLLABORATING INSTITUTIONS Forest Trends (http://www.forest-trends.org): Forest Trends is a non-profit organization that advances sustainable forestry and forestry’s contribution to community livelihoods worldwide. It aims to expand the focus of forestry beyond timber and promotes markets for ecosystem services provided by forests such as watershed protection, biodiversity and carbon storage. Forest Trends analyzes strategic market and policy issues, catalyzes connections between forward-looking producers, communities, and investors and develops new financial tools to help markets work for conservation and people. It was created in 1999 by an international group of leaders from forest industry, environmental NGOs and investment institutions. Center for International Forestry Research (http://www.cifor.cgiar.org): The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), based in Bogor, Indonesia, was established in 1993 as a part of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) in response to global concerns about the social, environmental, and economic consequences of forest loss and degradation. CIFOR research produces knowledge and methods needed to improve the wellbeing of forest-dependent people and to help tropical countries manage their forests wisely for sustained benefits. This research is conducted in more than two dozen countries, in partnership with numerous partners. Since it was founded, CIFOR has also played a central role in influencing global and national forestry policies. -

Humanitarian Crisis and Human Rights Violations

n the twenty-third week since the coup, the death toll rose to 899.1 Between July 3 to July 9, there were 10 clashes between the Kachin July 3-9 Independence Army (KIA) and the Burma Army (BA), 2 bomb attacks, I 10 armed clashes 35 instances of artillery shelling, and 6 airstrikes in the Kachin area. Fighting between the BA and KIA occurred in Waimaw and Shwegu, between KIA and Burma Army Kachin State. The military reportedly beefed up security at highway 35 artillery shellings checkpoints in Waingmaw town, on the Myitkyina – Bhamo road and on the Myitkyina – Putao road following the KIA attack of their forces on 2 bomb attacks these routes. Locals reported hearing gunshots in the residential areas 6 airstrikes of several townships in Kachin State, including Myitkyina and Hpakant. in the Kachin area There were also clashes between the BA and the Karenni Army. Clashes between the BA and PDF were reported in Dawei Township, Mandalay, and Kawlin township. Additionally, violence against regime informants February 1 - July 9 and collaborators were reported in several townships including in Paungde and Mawlamyine Kyun as well as in Yangon. In the meantime, 899 killed the Covid-19 cases continue to rise nationwide. On July 5, KIA closed all by Burma security forces border towns to minimize the spread of the disease. Myanmar reported 64 Covid-19 fatalities—the highest death toll since the military coup in February—and 4,320 new Covid-19 cases, on July 9. OTHER UPDATES ● The junta reportedly did Humanitarian Crisis and not release any Kachin political prisoners or Human Rights Violations journalists detained since the coup when freeing 2,296 prisoners across ● On July 2, in Sagaing Region, the BA troops killed around 41 the country last week. -

KACHIN STATE Myanmar

Myanmar Information Management Unit KACHIN STATE Myanmar 95°30'E 96°0'E 96°30'E 97°0'E 97°30'E 98°0'E 98°30'E 99°0'E 28°30'N Ü 28°30'N 28°0'N 28°0'N Nawngmun INDIA Puta-O Pannandin !( Nawngmun 27°30'N 27°30'N Putao oAirport Machanbaw Puta-O Pansaung !( Khaunglanhpu Machanbaw Khaunglanhpu Nanyun 27°0'N 27°0'N Don Hee !( !( Shin Bway Yang Sumprabum Sumprabum Tanai 26°30'N 26°30'N KACHIN Tsawlaw Tanai Lahe Tsawlaw Injangyang Htan Par Hkamti Kway 26°0'N o Khamti 26°0'N Airport Chipwi Injangyang Chipwi Myitkyina Hpakan Pang War Hpakan !( Kamaing !( 25°30'N 25°30'N Myitkyina Kan Mogaung Airport o Paik Ti Nampong Sadung !( oAir Base .!Myitkyina !( Mogaung Waingmaw Waingmaw SAGAING LAKE INDAWNGYI !( 25°0'N Hopin CHINA 25°0'N Mohnyin !( Mohnyin Sinbo Momauk Dawthponeyan !( Myo Hla 24°30'N !( 24°30'N Banmauk Bhamo Shwegu Bamaw SAGAING oAirport Momauk Shwegu Bhamo Indaw Katha !( Lwegel Mansi Pinlebu !( Maw !( !( Monekoe Hteik Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Manhlyoe 24°0'N (Manhero) Muse 24°0'N Mansi !( Wuntho Konkyan Namhkan Kilometers Kawlin Tigyaing 0 15 30 60 90 SHAN Laukkaing 95°30'E 96°0'E 96°30'E 97°0'E 97°30'E 98°0'E 98°30'E 99°0'E Tarmoenye !( Legend Elevation (Meter) Map ID: MIMU940v01 Takaung < 50 1,250 - 1,500 3,000 - 3,250 Data Sources : Myanmar Information Management Unit (MIMU) is a !( o Major Road Township Boundary River/Water Body Creation Date: 4 December 2012.A1 Airports Mabein 50 - 100 1,500 - 1,750 3,250 - 3,500 Base Map - MIMU ChinshwehawcommonNamtit resource of the Humanitarian Country Team Other Road District Boundary Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 Non-Perennial 100 - 250 1,750 - 2,000 3,500 - 3,750 Boundaries - WFP/MIMU (HCT) providing information management services, ^(!_ Capital including GIS mapping and analysis, to the humanitarian Railway State/Region Boundary Perennial 250 - 500 2,000 - 2,250 3,750 - 4,000 River and Stream - DCW Elevation : SRTM 90m and development actors both inside and outside of .! State Capital River and Stream International Boundary 500 - 750 2,250 - 2,500 4,000 - 7,007 Place names - Ministry of Home Affair Myanmar.