Poverty and Livelihood Diversification in Rural Liberia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberian Youth Reflect on Agriculture Livelihoods JANUARY 2017

N. Farese, Liberia GROWING A FUTURE Liberian Youth Reflect on Agriculture Livelihoods JANUARY 2017 Acknowledgements This research would not have been possible without the support of numerous individuals. We would like to thank all enumerators who worked hard to collect the data in the field and Mercy Corps staff in both Monrovia and Gbarnga, especially Ishmael Flomo and Rose Hemmer-Vitti for their logistics and management support. We would also like to thank the youth and elders in Bong County who took time out of their days to participate in this study, sharing their invaluable perspectives and experiences with our team. This study was made possible by a grant from The Technical and Operational Performance Support (TOPS) Program. The TOPS Micro Grants Program is made possible by the generous support and contribution of the American people through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of the materials produced through the Micro Grants do not necessarily reflect the views of TOPS, USAID, or the U.S. Government. Lead Researcher Gregory Scarborough, Consultant Technical Steering Committee Ed Brooks, Advisor Agriculture, Mercy Corps Doug Cooper, Director of Programs, Mercy Corps Liberia Matt Streng, Director Youth, Gender and Girls, Mercy Corps Penny Anderson, Country Director, Mercy Corps Liberia Sandrine Chetail, Director Agriculture, Mercy Corps Rose Hemmer-Vitti, Research, Learning and Research Manager, Mercy Corps Liberia Tara Noronha, Senior Advisor Youth Employment, Mercy Corps MERCY CORPS Growing a Future: -

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME XVI 1991 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL 1 1 0°W 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI -6 °N RIVER I 6 °N- 1 0 50 MARYLAND Geography Department ION/ 8 °W 1 University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XVI 1991 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. Elwood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Alfred B. Konuwa Butte College EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Henrique F. Tokpa Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS ABOUT LANDSELL K. CHRISTIE, THE LIBERIAN IRON ORE INDUSTRY AND SOME RELATED PEOPLE AND EVENTS: GETTING THERE 1 by Garland R. Farmer ZO MUSA, FONINGAMA, AND THE FOUNDING OF MUSADU IN THE ORAL TRADITION OF THE KONYAKA .......................... 27 by Tim Geysbeek and Jobba K. Kamara CUTTINGTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DURING THE LIBERIAN CIVIL WAR: AN ADMINISTRATOR'S EXPERIENCE ............ -

Food and Enterprise Development (Fed) Program for Liberia

FOOD AND ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT (FED) PROGRAM FOR LIBERIA FISCAL YEAR 2015 ANNUAL WORK PLAN This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development 0 for International Development USAID, and prepared by DAI. Fiscal Year 2015 Annual Work Plan Program Title: Food and Enterprise Development Program for Liberia (FED) Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Liberia Contract Number: 669-C-00-11-00047-00 Contractor: DAI Date of Publication: October 31, 2014 COVER PHOTO: Musu Dolo, 30, is a member of the vegetable farmers group that partners with the USAID Food and Enterprise Development Program for Liberia. To improve the farmers’ access to small amounts of capital, USAID FED helped the group of 20 women farmers create a Village Savings Loan Association (VSLA). Between October 2013 and June 2014, the women of Kweeigbein — which means We Ourselves — saved over L$148,000 or US$1,600 in Montserrado County. The group extended dozens of loans to its members and raised another L$28,000 in interest. All the money the group was able to raise stayed within the organization. Ms. Dolo took out two loans to purchase tools and inputs for her vegetable garden. The first loan, worth L$1,500, was used to buy a watering can. For the second loan, worth L$5,000, she bought fertilizer and seeds. In June 2014, the group paid out the shares of each member. DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. -

Global Food Security Response West Africa Rice Value Chain Analysis

ATTACHMENT II TO THE GLOBAL FOOD SECURITY RESPONSE WEST AFRICA RICE VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS GLOBAL FOOD SECURITY RESPONSE LIBERIA RICE STUDY microREPORT #157 AUGUST 2009 AUGUST 2009 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development.This publication It waswas producedprepared for by review DAI. by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chris Reynolds of DAI and Mike Field of ACDI/VOCA with funding from the Accelerated Microenterprise Advancement Project. Additional support was provided by consultants Dr. Sizi Subah and Macon Fiske Tubman. GLOBAL FOOD SECURITY RESPONSE LIBERIA RICE STUDY microREPORT #157 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................. 1 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE RICE INDUSTRY IN LIBERIA .......................... 2 II. BUSINESS ENABLING ENVIRONMENT .......................................................... 4 III. END MARKETS ....................................................................................................... 8 IV. CHAIN ANALYSIS ............................................................................................... 11 V. OPPORTUNITIES AND INCENTIVES FOR UPGRADING ....................... 19 VI. STRATEGY ........................................................................................................... -

Determinants of Liberian Farmgate Cocoa Prices

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2008 Determinants of Liberian Farmgate Cocoa Prices Alicia English University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Agricultural Economics Commons Recommended Citation English, Alicia, "Determinants of Liberian Farmgate Cocoa Prices. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2008. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3642 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Alicia English entitled "Determinants of Liberian Farmgate Cocoa Prices." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Agricultural Economics. Michael D. Wilcox - Roland K. Roberts, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Dayton M. Lambert, Daniel de la Torre Ugarte Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Alicia English entitled “Determinants of Liberian Farmgate Cocoa Prices.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Agricultural Economics. -

Liberia: Desk Study of Extension and Advisory Services Developing Local Extension Capacity (DLEC) Project June 2017

Liberia: Desk Study of Extension and Advisory Services Developing Local Extension Capacity (DLEC) Project June 2017 Acknowledgements Written by Vickie Sigman in collaboration with Kristin Davis of IFPRI, this analysis was compiled for the DLEC project under USAID Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-L-16-0002. This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Digital Green and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.” Developing Local Extension Capacity 2 CONTENTS Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 8 Conceptual Framework ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Methods ............................................................................................................................................................. 12 Results ................................................................................................................................................................ 12 Frame Conditions ........................................................................................................................................... -

1 Agricultural Extension in Post-Conflict Liberia: Progress Made and Lessons Learned

1 Agricultural Extension in Post-Conflict Liberia: Progress Made and Lessons Learned Austen Moore* University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois, USA Background to the Conflict and Rajalahti, 2010). Liberia received World Bank funding to expand its extension work- Conflict and agriculture have been intertwined force and place officers in every county, district in the Republic of Liberia since the country’s and klan (township), dramatically increas- formation by repatriated slaves from the ing the number of farmers reached by exten- USA and subsequent independence in 1847 sion information (MoA, 2007). Funding was (Pham, 2004; CIA, n.d.). Early in its history, also used to enhance domestic agricultural Liberians of American descent dominated research through the Central Agricultural the political process and began to annex Research Institute (CARI) in Bong County lands that traditionally belonged to indigen- and Cuttington University, Liberia’s leading ous groups (Humphreys and Richards, 2005; agricultural institution (FARA, n.d.). MoA, 2007). The Americo-Liberian minority However, benefits were not felt by all eventually controlled many of the nation’s Liberians. Highly productive plantations and most productive agricultural lands and nat- lucrative export agreements allowed the ural resources (Unruh, 2009). Americo-Liberian minority group to accumulate Many Americo-Liberian landowners prac- further wealth and prosperity (Sawyer, 2005), ticed a plantation-style agricultural model, while indigenous Liberians became dispro- while most indigenous farmers either served portionately poor (Pham, 2004; Humphreys as labor on large-scale plantations or practiced and Richards, 2005; GRC, 2007). Notably, small-scale farming. The plantation model the Liberian government authorized the lease led to relative productivity in staple and of 100,000 acres of prime agricultural land cash crops into the late 1970s (MoA, 2007). -

LIBERIA—Gender-Aware Programs and Women’S Roles in Agricultural Value Chains

Liberia Gender-aware Programs Public Disclosure Authorized and Women’s roles in agricultural Value Chains A Policy Memorandum Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by the World Bank’s Gender and Development Group (PRMGE) in collaboration with the Ministry of Gender and Development of Liberia (MOGD) Poverty Reduction and Economic Management—Gender and Development Group (PRMGE) Gender Action Plan—Gender Equality as Smart Economics—Strategic Country Support to the Government of Liberia Liberia Gender-aware Programs and Women’s roles in agricultural Value Chains A Policy Memorandum Prepared by the World Bank’s Gender and Development Group (PRMGE) in collaboration with the Ministry of Gender and Development of Liberia (MOGD) May 2010 List of Acronyms AIDP Agriculture and Infrastructure LISGIS Liberian Institute of Statistics and Development Project Geo-Information Services BIA Benefit Incidence Analysis LPMC Liberia Produce Marketing Corporation CARI Central Agricultural Research Institute LPPC Liberia Palm Products Corporation CAAS-Lib Comprehensive Assessment of the ME Marketing Extension Agricultural Sector–Liberia MOA Ministry of Agriculture CFSNS Comprehensive Food Security and MOIA Ministry of Internal Affairs Nutrition Survey MOPEA Ministry of Planning and Economic CWIQ Core Welfare Indicators Affairs Questionnaire MOGD Ministry of Gender and Development DHS Demographic and Health Survey MPW Ministry of Public Works DTIS Diagnostic Trade Integration Study NGO Non-Governmental -

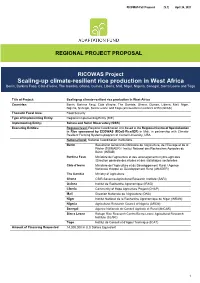

Scaling-Up Climate-Resilient Rice Production in West Africa

RICOWAS Full Proposal [V.1] April 26, 2021 REGIONAL PROJECT PROPOSAL RICOWAS Project Scaling-up climate-resilient rice production in West Africa Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo Title of Project: Scaling-up climate-resilient rice production in West Africa Countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo (all countries members of ECOWAS) Thematic Focal Area: Food Security Type of Implementing Entity: Regional Implementing Entity (RIE) Implementing Entity: Sahara and Sahel Observatory (OSS) Executing Entities: Regional level: Regional Coordination Unit based at the Regional Centre of Specialization in Rice sponsored by ECOWAS (RCoS-Rice/IER) in Mali, in partnership with Climate- Resilient Farming Systems program at Cornell University, USA National level: National Coordination Institutions Benin Secrétariat Général du Ministère de l'Agriculture, de l'Elevage et de la Pêche (SG/MAEP) / Institut National des Recherches Agricoles du Bénin (INRAB) Burkina Faso Ministère de l'agriculture et des aménagements hydro-agricoles /Direction générale des études et des statistiques sectorielles Côte d'Ivoire Ministère de l'Agriculture et du Développement Rural / Agence Nationale d'Appui au Développement Rural (ANADER) The Gambia Ministry of Agriculture Ghana CSIR-Savanna Agricultural Research Institute (SARI) Guinea Institut de Recherche Agronomique (IRAG) Liberia Community of -

Liberia Agricultural Marketing Study

Liberia Agricultural Marketing Study David Hughes Kerry Muir Eric Nelson Boima Rogers Undertaken foi' USAID/Liberia by Robert R. Nathan Asso., Inc. (Affiliate to Abt Asso., Inc. on AMIS project) June 1989 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION II. THE MARKETING OF COCOA AND COFFEE IN LIBERIA 3 9rld Production, Trade, and Prices 3 Cocoa 3 Coffee 7 Liberian Cocoa and Coffee 10 The Marketing System for Coffee and Cocoa 11 Internal Marketing 11 External Marketing 18 Marketing Costs 19 Export Prices for Liberian Coffee and Cocoa 20 Prices Paid to Growers 23 Relationship Between Grower and Export Price 25 Government Policy 27 Production of Coffee and Cocoa 28 Cost of Production 34 Agronomic Aspects of Cocoa and Coffee 40 Cocoa 40 Coffee 43 A Review of Marketing Systems for Coffee and Cocoa in Selected Other Producing Countries 46 Africa 46 Latin America 50 Asia and Oceania 54 Some Conclusions on Alternative Marketing Strtegies 55 Conclusions and Recommendations for the Coffee and Cocoa Sectors in Liberia 58 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued) Chapter Page III. RICE PRODUCTION AND MARKETING IN LIBERIA 64 Consumption Patterns for Rice in Liberia 64 Tsste and Preferences 64 Expenditure and Consumption Levels and Trends 67 Rice Production - Constraints and Potential 71 Agro-climatic Conditions 71 Farming Systems 72 Geographical Distribution of Rice Production 75 Trends in Rice Production 76 Government Policies on Rice 81 Rice Production Policies 82 Rice Marketing Policies 88 Macroeconomic Policies 92 The Market Structure for -

Liberian Agricultural Sector Investment Plan (Lasip Ii) (2018-2022)

LIBERIAN AGRICULTURAL SECTOR INVESTMENT PLAN (LASIP II) (2018-2022) By: MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE (MOA) MONROVIA, LIBERIA FINAL DRAFT JANUARY 2018 PREFACE As an agrarian economy, agriculture plays a critical role in the Liberian national economy. For this reason, governments over the years have been paying attention to agriculture. Nonetheless, the full potential of the sector is yet to be realized. Under the George Manneh Weah, Jr-led administration’s Pro-Poor Agenda for Prosperity and Development (PAPD), the agricultural sector is marked to be this driving force of the socio-economic transformation agenda. In line with the SDGs, the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP), the Regional Agricultural Investment Programme (RAIP), the Malabo Declaration and the Economic Community of West African States Agriculture Policy (ECOWAP), the Ministry of Agriculture led the process of formulating the second generation of the Liberia National Agriculture Investment Plan called Liberia Agricultural Sector Investment Plan (LASIP II), which builds on past progress and reaffirms the Government of Liberia’s commitment to transforming its agricultural sector. The process was supported by the ECOWAS and the Food and Nutrition Security Impact, Resilience, Sustainability and Transformation (FIRST) European Union – Food and Agriculture Organisation partnership programme, and in close consultation with donors, state and non-state actors as well as with active participation of relevant stakeholders in the sector. LASIP II represents a plan toward implementing the PAPD based on its pillar Economy and Jobs. The agricultural sector, through LASIP II, is expected to lead the Pro-Poor Agenda to ensure sustainable socio-economic transformation by focusing on five (5) pillars: Food and Nutrition Security; Development of Global Value Chains and Market Linkages; Strengthening of Agricultural Extension, Research and Development; Support of Sustainable Production and Natural Resource Management; and Governance and Institutional Strengthening. -

National Rice Development Strategy of Liberia Doubling Rice Production by 2008

National Rice Development Strategy of Liberia Doubling Rice Production by 2018 Ministry of Agriculture Monrovia, Liberia May 2012 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Rice is one of the staple food crops in Liberia. Rice is predominantly grown in upland environments by smallholder farmers, with a limited percentage devoted to lowland ecology. Presently, rice is largely cultivated once a year. The low input low risk production keeps the rice yields in uplands persistently low in Liberia. In 2010, about 296,090 t rice (before milling) was produced from 251,230 Ha with an average yield of 1.18 t/ Ha. The demand for rice however, is in far excess of the local production. In 2010, the total demand for milled rice in Liberia was estimated at 465,276 t. Being a popular food choice in Liberia, the annual per capita consumption of rice (133 Kg per year) is the highest in Africa. The gap between the demand and local production is met through importation of rice from countries such as China and USA. The large importation of rice adds pressure on country’s trade balance and the foreign exchange. Given the social and political significance of rice in Liberia, there is a strong need for increasing domestic rice production. In response to the global food crisis in 2008, the Government of Liberia (GoL) has acknowledged the importance of increasing rice production and has helped markets increase the rice supply by subsidizing the importation of rice. The Liberia’s National Rice Development Strategies (LNRDS) described in this document aims to achieve self sufficiency by doubling the local rice production by the year 2018.