Wild Park – National Park Biodiversity Action Programme 2018 – 2023

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

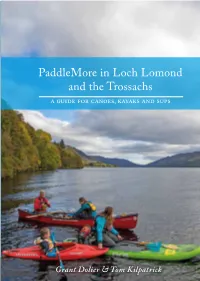

Paddlemore in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs a Guide for Canoes, Kayaks and Sups Paddlemore in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs a Guide for Canoes, Kayaks and Sups

PaddleMore in LochTrossachs PaddleMore Lomond and the PaddleMore in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs a guide for canoes, kayaks and sups PaddleMore in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs a guide for canoes, kayaks and sups Whether you want hardcore white water, multi-day touring Kilpatrick Tom & Dolier Grant trips or a relaxing afternoon exploring sheltered water with your family, you’ll find all that and much more in this book. Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park is long estab- lished as a playground for paddlers and attracts visitors from all over the world. Loch Lomond itself has over eighty kilometres of shoreline to explore, but there is so much more to the park. The twenty-two navigable lochs range from the vast sea lochs around Loch Long to small inland Loch Lomond bodies such as Loch Chon. & the Trossachs The rivers vary from relaxed meandering waterways like the Balvaig to the steep white water of the River Falloch and 9 781906 095765 everything in between. Cover – Family fun on Loch Earn | PaddleMore Back cover – Chatting to the locals, River Balvaig | PaddleMore Grant Dolier & Tom Kilpatrick Loch an Daimh Loch Tulla Loch Also available from Pesda Press Bridge of Orchy Lyon Loch Etive Loch Tay Killin 21b Tyndrum River Dochart River Loch 21a Fillan Iubhair Loch Awe 20 LOCH LOMOND & Crianlarich Loch Lochearnhead Dochart THE TROSSACHS 19 Loch NATIONAL PARK Earn Loch 5 River Doine 17 River Falloch Loch 32 Voil Balvaig 23 Ardlui 18 Loch Loch Sloy Lubnaig Loch Loch Katrine Arklet 12 Glen Finglas Garbh 3 10 Reservoir Uisge 22 Callander -

Official Statistics Publication for Scotland

Scotland’s Census 2011: Inhabited islands report 24 September 2015 An Official Statistics publication for Scotland. Official Statistics are produced to high professional standards set out in the Code of Practice for Official Statistics. © Crown Copyright 2015 National Records of Scotland 1 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 2. Main Points .................................................................................................................... 4 3. Population and Households ......................................................................................... 8 4. Housing and Accommodation .................................................................................... 12 5. Health ........................................................................................................................... 15 6. Ethnicity, Identity, Language and Religion ............................................................... 16 7. Qualifications ............................................................................................................... 20 8. Labour market ............................................................................................................. 21 9. Transport ...................................................................................................................... 27 Appendices ..................................................................................................................... -

Scottish Birds

ISSN 0036-9144 SCOTTISH BIRDS THE JOURNAL OF THE SCOTTISH ORNITHOLOGISTS' CLUB Volume 9 No. 4 WINTER 1976 Price 7Sp SCOTTISH BIRD REPORT 1975 1977 SPECIAL INTEREST TOURS by PER'EGRINE HOLIDAYS Director s: Raymond Hodgkins, MA. (Oxon)MTAI. Patricia Hodgkins, MTAI a nd Neville Wykes, (Acct.) All Tours by scheduled Air and Inclusive. Most with guest lecturers and a tour manager. *Provisional SPRING IN VENICE . Mar 19-26 . Art & Leisure £139 SPRING IN ATHENS ... Mar 22-31 . Museums & Leisure £125 SPRING IN ARGOLlS ... Mar 22-31 . Sites & Flowers £152 PELOPONNESE . .. Apr 1-15 ... Birds & Flowers £340 CRETE . Apr 1·15 .. Birds & Flowers £330 MACEDONIA . Apr 28-May 5 . .. Birds with Peter Conder £210 ANDALUSIA .. May 2·14 . Birds & Flowers £220* PELOPONNESE & CRETE ... May 24-Jun 7 . .. Sites & Flowers £345 CRETE (8 days) . , . May 24, 31, June 7 ... Leisure £132 NORTHERN GREECE ... Jun 8·22 ... Mountain Flowers £340 RWANDA & ZAIRE . Jul 15·Aug 3 ... Gorillas with John £898 Gooders. AMAZON & GALAPAGOS . .. Aug 4-24 ... Dr David Bellamy £1064 BIRDS OVER THE BOSPHORUS ... Sep 22-29 ... Eagles with £195 Dr Chris Perrins. KASHMIR & KULU . .. Oct 14-29 ... Birds & Flowers £680* AUTUMN IN ARGOLlS ... Oct 12·21 ... Birds & Sites £153* AUTUMN IN CRETE ... Nov 1-8 ... Birds & Leisure £154* Brochures by return. Registration without obligation. PEREGRINE HOLIDAYS at TOWN AND GOWN TRAVEL, 40/41 SOUTH PARADE, AGENTS SUMMERTOWN, OXFORD, OX2 7JP. Phone Oxford (0865) 511341-2-3 Fully Bonded Atol No. 275B RARE BIRDS IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND by J. T. R. SHARROCKand E. M. SHARROCK This new, much fuller, companion work to Dr Sharrock's Scarce Migrant Birds in Britain and Ireland (£3.80) provides a textual and visual analysis for over 221 species of rare birds seen in these islands. -

NPP Special Qualities

LOCH LOMOND NORTH SPECIAL QUALITIES OF LOCH LOMOND LOCH LOMOND NORTH Key Features Highland Boundary Fault Loch Lomond, the Islands and fringing woodlands Open Uplands including Ben Vorlich and Ben Lomond Small areas of settled shore incl. the planned villages of Luss & Tarbet Historic and cultural associations Rowardennan Forest Piers and boats Sloy Power Station West Highland Way West Highland Railway Inversnaid Garrison and the military roads Islands with castles and religious sites Wildlife including capercaillie, otter, salmon, lamprey and osprey Summary of Evaluation Sense of Place The sense of place qualities of this area are of high importance. The landscape is internationally renowned, so its importance extends far beyond the Park boundaries. The North Loch Lomond area is characterised by a vast and open sense of place and long dramatic vistas. The loch narrows north of Inveruglas and has a highland glen character with narrow and uneven sides and huge craggy slopes. The forests and woodlands along the loch shores contrast with surrounding uplands to create a landscape of high scenic value. The Loch Lomond Islands are unique landscape features with a secluded character, they tend to be densely wooded and knolly and hummocky in form. The upland hills, which include Ben Lomond and Ben Vorlich, surrounding Loch Lomond provide a dramatic backdrop to the loch. The upland hills are largely undeveloped and have an open and wild sense of place. However, there are exceptions, with evidence of pylons and masts on some hills and recreational pressures causing the erosion of footpaths on some of the more popular peaks. -

Bathing Water Profile for Luss

Bathing Water Profile for Luss Luss, Scotland __________________ Current water classification https://www2.sepa.org.uk/BathingWaters/Classifications.aspx Today’s water quality forecast http://apps.sepa.org.uk/bathingwaters/Predictions.aspx _____________ Description Luss Bay is a relatively small freshwater bay of about 400 metres long situated on the midwest shore coast of Loch Lomond west of Inchlonaig Island. It is located at the conservation village of Luss and is owned by Luss Estates. The area is part of the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park. The sandy beach is ideal for paddling and is often used by families with young children; however, the northern portion of the beach is privately owned and is not accessible to the public. Site details Local authority Argyll and Bute Council Year of designation 1999 Water sampling location NS 36015 93296 EC bathing water ID UKS7616033 Catchment description The catchment draining into the bathing water extends to 37 km2. The area is mountainous with the highest peaks in the catchment being Beinn Eich at 703 metres in the north-west and Deinn Chaorach at 713 metres to the west of the bay. These two peaks form the steep valley along which Luss Water flows towards the bathing water. The area is predominantly rural (99%) with agriculture the major land use. The catchment supports mixed sheep and cattle farming. Less than one percent of the bathing water catchment is urban. The main population centre is Luss. The main rivers within the bathing water catchment are the Luss Water, Auchengavin Burn, Sron an Laoign Burn and Mollochan Burn. -

Rossdhu Atlntde Ci Iy

DONATED TO THE \01 COBOURG PUBLIC LIBRARY to\l po- BY of ( ORVAL O.CALHOUN, ON MARCH 10-1992. Rossdhu atlntde cI Iy e An illustrated guide to the homelof The Chiefs of Clan Colquhoun since 12th century. ORV & CLAn CALHOUN 448 BURNHAM ST. COBOURG, ONT. K9A 2W7 7n~~ /0-/f'1:<- Printed and Produced in Great Britain by Photo Precision Ltd., St. Ives, Hunts. co 0 LIBRARY l'iAR 1 1 1992 Home of the Chiefs of the Clan Colquhoun by Sir lain Moncrieffe of that Ilk Ph.D., Albany Herald Rossdhu in Luss, Gaelic ros dubh for the 'Black Headland', where stands the stately Georgian house and romantic ruined mediaeval castle of the Chiefs of the Clan Colquhoun, is one of the most beautiful places known to man. A wooded peninsula guarded on three sides by the bonny banks of Loch Lomond, so celebrated in the famous Harry Lauder song set to the ancient tune of 'Binorie, 0 Binorie', Rossdhu looks out across the enchanted, treacherous waters of the loch, studded with apparently peaceful islands like gems. In the Middle Ages on one of these islands, Inchmurrin, the then chief, John Colquhoun 10th of Luss, was savagely murdered by a band of Hebridean marauders led by the Maclean chief with whom he was attempting to negotiate peace. And in these fair-faced but swift-changing waters centuries later, during the reign of Queen Victoria, Sir James Colquhoun 28th of Luss, with four of his gillies, drowned within earshot of Rossdhu while sailing homewards from stalking red deer on the Island of Inchlonaig: their desperate cries for help may have been heard ashore but mistaken for cheerful shouts. -

Loch Lomond Islands

Loch Lomond Islands Deer Management Group Deer Management Plan 2019 - 2024 Prepared by Kevin McCulloch, Scottish Natural Heritage Updated April 2020 Loch Lomond Islands Deer Management Plan 2019 - 2024 Introduction 3 The Purpose of the DMG 3 Objectives 3 Plan Implementation 3 DMG location/Area 4 Management Units 4 Designations 4 Data Gathering 5 Habitat Monitoring - Herbivore Impact Assessment Surveys 5 Historical Monitoring (baseline data) 5 Previous Monitoring 5 Most Recent Monitoring 5 Conclusion of HIA Results 6 Deer Counts 7 Other Herbivores 8 Other Factors Preventing Regeneration 8-9 Density estimates related to targets 9 Cull Information 9 Cull Action Plan 9 Seasons & Authorisations 10 Recommendations 10 Carcass Disposal 10 Cull Targets: Past and Present 11 Cull Targets: Ongoing Reduction 11 Public Access 12 Fencing 12 Sustainable Deer Management and the Public Interest 12 Annual Evaluation and review 13-14 Next Review of DMP 14 Appendix 1 – The 5 Types of Designations in the DMG 15 Appendix 2 - Designated Sites and there Conservation Objectives 16 Appendix 3 – Maps of Deer Counts 17-19 Appendix 4 – Breakdown of Cull Results 20 Appendix 5 – Deer Population Model 21 Appendix 6 – Summary of island landownership 22 2 Loch Lomond Islands Deer Management Plan 2019 - 2024 Introduction The Loch Lomond Islands hold one of the few fallow deer populations in Scotland. Deer are free to swim from island to island and to the mainland, with fallow populations also present on the East mainland near Balmaha and the West mainland near Luss. It is assumed immigration and emigration occurs within the fallow deer population naturally at specific times of year and/or due to disturbance. -

Historic Forfar, the Archaeological Implications of Development

Freshwater Scottish loch settlements of the Late Medieval and Early Modern periods; with particular reference to northern Stirlingshire, central and northern Perthshire, northern Angus, Loch Awe and Loch Lomond Matthew Shelley PhD The University of Edinburgh 2009 Declaration The work contained within this thesis is the candidate’s own and has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Signed ……………………………………………………………………………… Acknowledgements I would like to thank all those who have provided me with support, advice and information throughout my research. These include: Steve Boardman, Nick Dixon, Gordon Thomas, John Raven, Anne Crone, Chris Fleet, Ian Orrock, Alex Hale, Perth and Kinross Heritage Trust, Scottish Natural Heritage. Abstract Freshwater loch settlements were a feature of society, indeed the societies, which inhabited what we now call Scotland during the prehistoric and historic periods. Considerable research has been carried out into the prehistoric and early historic origins and role of artificial islands, commonly known as crannogs. However archaeologists and historians have paid little attention to either artificial islands, or loch settlements more generally, in the Late Medieval or Early Modern periods. This thesis attempts to open up the field by examining some of the physical, chorographic and other textual evidence for the role of settled freshwater natural, artificial and modified islands during these periods. It principally concentrates on areas of central Scotland but also considers the rest of the mainland. It also places the evidence in a broader British, Irish and European context. The results indicate that islands fulfilled a wide range of functions as secular and religious settlements. They were adopted by groups from different cultural backgrounds and provided those exercising lordship with the opportunity to exercise a degree of social detachment while providing a highly visible means of declaring their authority. -

Scottish Natural Heritage FACTS and FIGURES 1996-97

Scottish Natural Heritage FACTS AND FIGURES 1996-97 Working with Scotland’s people to care for our natural heritage PREFACE SNH Facts and Figures 1996/97, contains a range of useful facts and statistics about SNH’s work and is a companion publication to our Annual Report. SNH came into being on 1 April 1992, and in our first Annual Report we published an inventory of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). After an interval of five years it is appropriate to now update this inventory. We have also provided a complete Scottish listing of National Nature Reserves, National Scenic Areas, European sites and certain other types of designation. As well as the information on sites, we have also published information on our successes during 1996/97 including partnership funding of projects, details of grants awarded, licences issued and our performance in meeting our standards for customer care. We have also published a full list of management agreements concluded in 1996/97. We hope that those consulting this document will find it a useful and valuable record. We are committed to being open in the way we work and if there is additional information you require, contact us, either at any local offices (detailed in the telephone directory) or through our Public Affairs Branch, Scottish Natural Heritage, 12 Hope Terrace, Edinburgh EH9 2AS. Telephone: 0131 447 4784 Fax: 0131 446 2277. Table of Contents LICENCES 1 Licences protecting wildlife issued from 1 April 1996 to 31 March 1997 under various Acts of Parliament 1 CONSULTATIONS 2 Natural -

Freshwater Scottish Loch Settlements of The

Freshwater Scottish loch settlements of the Late Medieval and Early Modern periods; with particular reference to northern Stirlingshire, central and northern Perthshire, northern Angus, Loch Awe and Loch Lomond Matthew Shelley Appendices containing maps, map details, illustrations and tables to accompany the thesis. PhD The University of Edinburgh 2009 Declaration The work contained within this thesis is the candidate’s own and has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Signed ……………………………………………………………………………… Contents Bibliography 1 Appendix 1: Loch settlement structures 38 Chart A: Island sizes and situations 39 Chart B: Locations within lochs 45 Appendix 2: Loch settlements on early maps 51 The Ortelius loch settlements 52 The Mercator 1595 loch settlements 53 Map-makers’ images of Loch Lomond 54 Pont’s Loch settlement depictions 55 Loch settlements of the Gordon manuscript maps 60 Loch settlements in the Blaeu atlas 64 Maps details from the Aberdeen area 69 Appendix 3: Surveys and historic images 71 Inchaffray 72 Lake of Menteith, Inchmahome Priory 75 Little Loch Shin 77 Loch Awe, Inishail 79 Loch Awe, Kilchurn Castle 80 Loch Brora 83 Loch Dochart 85 Loch Doon 87 Loch Dornal 91 Loch of Drumellie 93 Loch Earn, Neish Isle 95 Loch an Eilean 97 Loch of Forfar 99 Loch Kennard 101 Loch of Kinnordy 103 Lochleven 104 Loch Lomond, Eilean na Vow 107 Loch Rannoch 109 Loch Rusky 111 Loch Tay, Priory Island 113 Loch Tay, Priory Island Port 116 Loch Tulla 117 Loch Tummel 119 Lochore 121 Loch Venachar 122 Lochwinnoch 124 Appendix 4: Distribution maps 126 Loch settlements of the Pont manuscript maps 127 Key and symbological table 128 Loch settlements of the Gordon manuscripts maps 131 Key and symbological table 132 Loch settlements of the 1654 Blaeu atlas 134 Key and symbological table 135 Sources of information for all loch settlements discussed in thesis 137 Appendix 5: Loch Tulla shoe 143 Expert interpretation 143 Pictures 144 Report 149 Bibliography Abbreviated ALCPA: Acts of the Lords of Council in Public Affairs, 1501-1554. -

Tarbet Isle Loch Lomond Argyll & Bute

NORTHLIGHT HERITAGE Tarbet Isle REPORT: 121 PROJECT ID: 4405161 Loch Lomond DATA STRUCTURE REPORT Argyll & Bute Northlight Heritage | Project: 4405161 | Report: 121 | 05/03/2015 Northlight Heritage Studio 406 | South Block | 64 Osborne Street | Glasgow | G1 5QH web: www.northlight-heritage.co.uk | tel: 0845 901 1142 email: [email protected] Tarbet Isle, Tarbet, Loch Lomond, Argyll, Scotland NGR: NN 3288 0540 Data Structure Report on behalf of Peter McFarlin and Preston McFarland Cover Plate: Trench 2 across the southern end of the structure. Report by: Heather F James Illustrations by: Ingrid Shearer Edited by: Olivia Lelong Director: Heather F James Excavation Team: Peter McFarlin, Preston McFarland, Alison Blackwood, Ian Marshall, Ewen Smith, Tessa Poller, Fiona Jackson, Sue Furness, Libby King & Margaret Gardiner. Approved by: .............. .............................................. Date: .........5/03/2015........................... This Report has been prepared solely for the person/party which commissioned it and for the specifically titled project or named part thereof referred to in the Report. The Report should not be relied upon or used for any other project by the commissioning person/party without first obtaining independent verification as to its suitability for such other project, and obtaining the prior written approval of York Archaeological Trust for Excavation and Research Limited (“YAT”) (trading as Northlight Heritage). YAT accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this Report being relied upon or used for any purpose other than the purpose for which it was specifically commissioned. Nobody is entitled to rely upon this Report other than the person/party which commissioned it. YAT accepts no responsibility or liability for any use of or reliance upon this Report by anybody other than the commissioning person/party. -

Loch Lomond Byelaws 2013

Loch Lomond Byelaws 2013 lochlomond-trossachs.org Loch Lomond Byelaws 2013 | 1 98394 LOC LOM 24pp.indd 1 14/03/2013 13:27 IntroductIon Loch Lomond is the largest body of freshwater in mainland Britain. The loch and its islands are used by visitors throughout the year for a range of recreation interests, including boating, water-skiing, canoeing, camping, fishing and sailing. The loch is also important for a range of environmental interests and as the source of drinking water for millions of Scots. Its islands are special places containing high quality semi-natural habitats and providing homes to rare species. The islands are protected under a range of environmental designations. Many businesses and communities around the loch, such as marinas, cruises, scheduled water bus services, boatyards, hotels, B&Bs and visitor attractions, thrive on the opportunities that Loch Lomond offers. There is a need to balance environmental, economic and social pressures on Loch Lomond; to ensure that the loch can be enjoyed safely and responsibly; and to prevent the things that make it special from being over-used or degraded. The Byelaws The Loch Lomond Byelaws were introduced in 1996 by the Loch Lomond Regional Park Authority. In 2002 Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park Authority became responsible for the byelaws, which were revised in 2007. A further review took place in 2012 and the revised Loch Lomond Byelaws were approved by Scottish Government Ministers in February 2013. The Byelaws set out in this publication are effective from the 1st April 2013. 2 | lochlomond-trossachs.org 98394 LOC LOM 24pp.indd 2 14/03/2013 13:27 The NaTioNal Park auThoriTy The National Park Ranger Service undertakes most of the byelaw enforcement and compliance activity on the loch.