Inquiry Into the Jabiluka Uranium Mine Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Submission to the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission

Roman Oszanski A Submission to the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission Preamble I have chosen not to follow the issues papers: their questions are more suited to those planning to expand the nuclear industry, and many of the issues raised are irrelevant if one believes that, based on the evidence, the industry should be left to die a natural death, rather than being supported to the exclusion of more promising technologies. Executive Summary The civil nuclear industry is in decline globally. [Ref charts on existing reactors, rising costs]. It is not an industry of the future, but of the past. If it were not for the intimate connection to the military industry, it would not exist today. There is no economic advantage to SA in expanding the existing industry in this state. Nuclear power does not offer a practical solution to climate change: total lifetime emissions are likely to be (at best) similar to those of gas power plants, and there is insufficient uranium to replace all the goal fired generators. A transition to breeder technologies leaves us with major problems of waste disposal and proliferation of weapons material. Indeed, the problems of weapons proliferation and the black market in fissionable materials mean that we should limit sales of Uranium to countries which are known proliferation risks, or are non- signatories to the NNPT: we should ban sales of Australian Uranium to Russia and India. There is a current oversupply of enrichment facilities, and there is considerable international concern at the possibility of using such facilities to enrich Uranium past reactor grade to weapons grade. -

The Builders Labourers' Federation

Making Change Happen Black and White Activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, Union and Liberation Politics Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cook, Kevin, author. Title: Making change happen : black & white activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, union & liberation politics / Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall. ISBN: 9781921666728 (paperback) 9781921666742 (ebook) Subjects: Social change--Australia. Political activists--Australia. Aboriginal Australians--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--20th century. Australia--Social conditions--20th century. Other Authors/Contributors: Goodall, Heather, author. Dewey Number: 303.484 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover images: Kevin Cook, 1981, by Penny Tweedie (attached) Courtesy of Wildlife agency. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History RSSS and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National -

Dollars for Death Say No to Uranium Mining & Nuclear Power

Dollars for Death Say No to Uranium Mining & Nuclear Power Jim Green & Others 2 Dollars for Death Contents Preface by Jim Green............................................................................3 Uranium Mining ...................................................................................5 Uranium Mining in Australia by Friends of the Earth, Australia..........................5 In Situ Leach Uranium Mining Far From ‘Benign’ by Gavin Mudd.....................8 How Low Can Australia’s Uranium Export Policy Go? by Jim Green................10 Uranium & Nuclear Weapons Proliferation by Jim Falk & Bill Williams..........13 Nuclear Power ...................................................................................16 Ten Reasons to Say ‘No’ to Nuclear Power in Australia by Friends of the Earth, Australia...................................................................16 How to Make Nuclear Power Safe in Seven Easy Steps! by Friends of the Earth, Australia...................................................................18 Japan: One Year After Fukushima, People Speak Out by Daniel P. Aldrich......20 Nuclear Power & Water Scarcity by Sue Wareham & Jim Green........................23 James Lovelock & the Big Bang by Jim Green......................................................25 Nuclear Waste ....................................................................................28 Nuclear Power: Watt a Waste .............................................................................28 Nuclear Racism .................................................................................31 -

The Rock Art of Madjedbebe (Malakunanja II)

5 The rock art of Madjedbebe (Malakunanja II) Sally K. May, Paul S.C. Taçon, Duncan Wright, Melissa Marshall, Joakim Goldhahn and Inés Domingo Sanz Introduction The western Arnhem Land site of Madjedbebe – a site hitherto erroneously named Malakunanja II in scientific and popular literature but identified as Madjedbebe by senior Mirarr Traditional Owners – is widely recognised as one of Australia’s oldest dated human occupation sites (Roberts et al. 1990a:153, 1998; Allen and O’Connell 2014; Clarkson et al. 2017). Yet little is known of its extensive body of rock art. The comparative lack of interest in rock art by many archaeologists in Australia during the 1960s into the early 1990s meant that rock art was often overlooked or used simply to illustrate the ‘real’ archaeology of, for example, stone artefact studies. As Hays-Gilpen (2004:1) suggests, rock art was viewed as ‘intractable to scientific research, especially under the science-focused “new archaeology” and “processual archaeology” paradigms of the 1960s through the early 1980s’. Today, things have changed somewhat, and it is no longer essential to justify why rock art has relevance to wider archaeological studies. That said, archaeologists continued to struggle to connect the archaeological record above and below ground at sites such as Madjedbebe. For instance, at this site, Roberts et al. (1990a:153) recovered more than 1500 artefacts from the lowest occupation levels, including ‘silcrete flakes, pieces of dolerite and ground haematite, red and yellow ochres, a grindstone and a large number of amorphous artefacts made of quartzite and white quartz’. The presence of ground haematite and ochres in the lowest deposits certainly confirms the use of pigment by the early, Pleistocene inhabitants of this site. -

Contents 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11

April edition 2004 Welcome to the latest edition of Our Community Matters, our regular free community update. It is yet another benefit of membership of www.ourcommunity.com.au - the premier destination for Australia's 700,000 community, education and non-profit groups. Ourcommunity.com.au provides community groups with the latest funding and fundraising news as well as practical management and board and committee advice and the opportunity to list for free online donations through the Australian Giving Centre. A summary of our services is listed at the end of this newsletter. If you have trouble reading this newsletter or have any comments please let us know at [email protected]. In this Issue Contents 1. Welcome from Rhonda Galbally, CEO of Our Community. 2. Survey of the barriers faced by NGOs in having their voices heard. 3. Registrations roll in for the Communities in Control conference as panels confirmed. 4. Getting to know your local area profile – now get the stats that matter! Our Community Leaders – Great Australian Leaders in Focus with High Court Justice 5. Michael Kirby. 6. What are the keys behind innovative towns? A new report tries to unlock the secrets. 7. Why groups need to spend more time involving young people. 8. Don’t forget to sign up for the Community Business Partnership Brokerage Service. 9. Instant Savvy: Critical Incident Response. 10. When destiny is shaped by a postcode. 11. Community Briefs - bits and pieces from the community sector. 12. Fast Forward ©Copyright www.ourcommunity.com.au Page 1 April 2004 1. Welcome by Rhonda Galbally AO, CEO of ourcommunity.com.au. -

Gundjehmi Aboriginal Corporation Speech

Medical Association for Prevention of War www.mapw.org.au Archived Resource: Paper from IPPNW XIIIth World Congress 1998 Gundjehmi Aboriginal Corporation Speech Author: Jacqui Katona Date: 1998 I speak here today on behalf of the Mirrar people, my family and my countryman who oppose the development of Jabiluka. I'd like to acknowledge the Wurundjeri people, traditional owners of this area, for their liberation is linked to our own and although is takes place in other forums we know their experienced is intimately linked with Aboriginal people across Australia. My people come from Kakadu. One of the best known destinations for many international visitors because of the important and visible connection between my people and the land, Kakadu is our home. It is the place which nurtures our families, and provides us with obligations to protect and maintain our heritage, our future, and our past. For us the threat of Jabiluka is an issue of human rights. Kakadu's unique cultural and natural properties are not only recognised by our people but also by the rest of the world in its inscription on the world heritage list. Even the World Heritage committee recognises that human rights are connected with it's own Convention. It has said: that human rights of indigenous peoples must be taken into account in the protection of world heritage properties; that conservation of country must take place with direction from indigenous people, and; that the continuing violation of human rights places properties in danger because of our integral relationship with the land. The continuing dominance of government and industry organisation over the authority of our people erodes our rights on a daily basis. -

Chain-Reaction-#114-April-2012.Pdf

Issue #114 | April 2012 RRP $5.50 The National Magazine of Friends of the Earth Australia www.foe.org.au ukushima fone year on • Occupy Texas Can we save the • Fighting Ferguson’s nuclear dump Murray-Darling? • A smart grid and seven energy sources • How low can uranium export policy go? 1 Chain Reaction #114 April 2012 Contents Edition #114 − April 2012 Regular items Publisher FoE Australia News 4 FoE Australia Contacts Friends of the Earth, Australia Chain Reaction ABN 81600610421 FoE Australia ABN 18110769501 FoE International News 8 inside back cover www.foe.org.au youtube.com/user/FriendsOfTheEarthAUS Features twitter.com/FoEAustralia facebook.com/pages/Friends-of-the-Earth- MURRAY-DARLING NUCLEAR POWER & FUKUSHIMA Australia/16744315982 AND RIVER RED GUMS Fighting Ferguson’s Dump 20 flickr.com/photos/foeaustralia Can we save the Natalie Wasley Chain Reaction website Murray-Darling Basin? 10 Global Conference for a www.foe.org.au/chain-reaction Jonathan La Nauze Nuclear Power Free World 22 Climate change and the Cat Beaton and Peter Watts Chain Reaction contact details Murray-Darling Plan 13 Fukushima − one year on: PO Box 222,Fitzroy, Victoria, 3065. Jamie Pittock photographs 24 email: [email protected] phone: (03) 9419 8700 River Red Gum vegetation Australia’s role in the survey project 14 Fukushima disaster 26 Chain Reaction team Aaron Eulenstein Jim Green Jim Green, Kim Stewart, Georgia Miller, Rebecca Pearse, Who is to blame for the Richard Smith, Elena McMaster, Tessa Sellar MIC CHECK: Fukushima nuclear disaster? 28 Layout -

The Mirarr: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow

The Mirarr: yesterday, today and tomorrow. A socioeconomic update. Prepared by the GUNDJEIHMI ABORIGINAL CORPORATION August, 2010 Published in Australia in 2010 by the Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation, 5 Gregory Place, Jabiru, Northern Territory. Text: Andrew Masterson Additional contributions: Justin O’Brien, Geoffrey Kyle Editing: Andrew Masterson Design and layout: Tristan Varga-Miller/The Mojo Box Photography: Dominic O’Brien Additional photography: Craig Golding, Graphics: Sahm Keily Printed by Sovereign Press, Ballarat, Victoria All rights reserved. Copyright 2010, Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation. Apart from fully credited brief excerpts used in the process of review or fair dealing, no part of this document may be reproduced in any form without the express written consent of the copyright holder. ISBN 978-0-9808312-0-7 Cover photo: Djabalukga Wetlands, Kakadu National Park 2 The Mirarr: yesterday, today and tomorrow Contents Executive Officer’s Report 8 Board of Directors 11 Acronyms 12 Closing the Gap 13 Our Past, Our Future 15 The Gudjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation, Past and Present 19 Staff Profiles 25 Cultural Development 29 Community Development 41 Healthy Lives 47 Economic Development 51 Land, Water, People 59 Looking to the Future 67 Financial statements 73 The Mirarr: yesterday, today and tomorrow 3 About this report The Mirarr: yesterday, today and tomorrow: a socioeconomic update sets out to summarise the activities of the Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation in its mission to meet the needs and aspirations of its owners and constituents, the Mirarr people. The report traces the history of the Corporation. It describes its current holdings and business model, and outlines the exciting opportunities present in the next period of its operations. -

![Margarula V Rose [1999] NTSC 22 PARTIES](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9510/margarula-v-rose-1999-ntsc-22-parties-1399510.webp)

Margarula V Rose [1999] NTSC 22 PARTIES

Margarula v Rose [1999] NTSC 22 PARTIES: YVONNE MARGARULA v SCOTT ROSE TITLE OF COURT: SUPREME COURT OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY JURISDICTION: SUPREME COURT OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY EXERCISING TERRITORY JURISDICTION FILE NO: JA79 of 1998 (9810168) DELIVERED: 12 March 1999 HEARING DATES: 15, 22 and 23 February 1999 JUDGMENT OF: RILEY J REPRESENTATION: Counsel: Appellant: D. Dalrymple Respondent: R. Webb; J. Whitbread Solicitors: Appellant: Dalrymple & Associates Respondent: Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions Judgment category classification: B Judgment ID Number: ril99005 Number of pages: 36 ril99005 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA AT DARWIN Margarula v Rose [1999] NTSC 22 No. JA79 of 1998 IN THE MATTER OF the Justices Act AND IN THE MATTER OF an appeal against conviction and sentence handed down in the Court of Summary Jurisdiction at Darwin BETWEEN: YVONNE MARGARULA Appellant AND: SCOTT ROSE Respondent CORAM: RILEY J REASONS FOR JUDGMENT (Delivered 12 March 1999) [1] On 1 September 1998 the appellant was found guilty of having trespassed unlawfully on enclosed premises, namely a large storage container owned by Energy Resources of Australia (herein ‘ERA’), contrary to s5 of the Trespass Act. She was convicted and ordered to pay a $500 fine and $20 victim levy. She appeals against both conviction and sentence. The grounds of appeal, which were amended at the beginning of the hearing, appear in the document filed on 16 February 1999. 1 [2] At the hearing before the learned Magistrate many facts were agreed and the only witnesses called were Mr Holger Topp, an employee of ERA, and the appellant. -

Collection Name

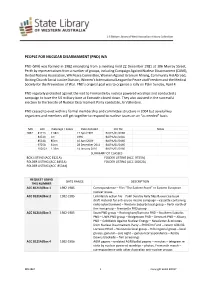

PEOPLE FOR NUCLEAR DISARMAMENT (PND) WA PND (WA) was formed in 1982 emanating from a meeting held 22 December 1981 at 306 Murray Street, Perth by representatives from a number of groups, including Campaign Against Nuclear Disarmament (CANE), United Nations Association, WA Peace Committee, Women Against Uranium Mining, Community Aid Abroad, Uniting Church Social Justice Division, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and the Medical Society for the Prevention of War. PND’s original goal was to organise a rally on Palm Sunday, April 4. PND regularly protested against the visit to Fremantle by nuclear powered warships and conducted a campaign to have the US military base at Exmouth closed down. They also assisted in the successful election to the Senate of Nuclear Disarmament Party candidate, Jo Vallentine. PND ceased to exist within a formal membership and committee structure in 2004 but several key organizers and members still get together to respond to nuclear issues on an “as needed” basis. MN ACC meterage / boxes Date donated CIU file Notes 2867 8121A 2.38m 17 April 1991 BA/PA/01/0166 8451A 1m 1996 BA/PA/01/0166 8534A 85cm 16 April 2009 BA/PA/01/0166 9725A 61cm 28 December 2011 BA/PA/01/0166 10202A 1.36m 14 January 2016 BA/PA/01/0166 SUMMARY OF CLASSES BOX LISTING (ACC 8121A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 9725A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 8451A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 10202A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 8534A) REQUEST USING DATE RANGE DESCRIPTION THIS NUMBER ACC 8121A/Box 1 1982-1985 Correspondence – File; “The Eastern Front” re Eastern European nuclear -

Wild Things Study Guide

PRODUCED AND DIRECTED BY SALLY INGLETON Writer Dave Crewe https://theeducationshop.com.au STUDY http://www.metromagazine.com.au © ATOM 2021 ISBN: 978-1-76061-398-3 GUIDE CONTENT HYPERLINKS 3 SYNOPSIS 4 DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT 4 PEOPLE IN THE FILM 5 CURRICULUM LINKS 12 ACTIVITIES 12 The Evolution of Environmental Activism 15 Imagery to Effect Change 16 Protest Songs 17 Water in Aboriginal Culture 18 Protecting The Tarkine 18 Deforestation and Climate Change Devastation 19 Coral Bleaching and the Great Barrier Reef 20 Adani & Innovation – Fossil Fuels and the Future 21 WORKSHEETS 21 Forests and Deforestation 22 School Strikes for Climate 23 The Ethics of Illegal Activism 24 The Franklin River Blockade 25 Hippies or Heroes? The Representation of Protestors 26 Aboriginal Connection to © ATOM 2020 © ATOM Country 27 Activism Begins at Home 2 SYNOPSIS Wild Things follows a new generation of environmental activists that are mobilising against forces more powerful than themselves and saying, enough. Armed only with mobile phones, this growing army of ecowarriors will do whatever it takes to save their futures from the ravages of climate change. From chaining themselves to coal trains, sitting high in the canopy of threatened rainforest or locking onto bulldozers, their non-violent tactics are designed to generate mass action with one finger tap. Against a backdrop of drought, fire and floods; we witness how today’s environmentalists are making a difference and explore connections with the past through the untold stories of previous campaigns. Surprisingly the methods of old still have currency when a groundswell of schoolkids inspired by the actions of 16-year-old Swedish student Greta Thunberg say, “change is coming” and call a national strike demanding action against global warming. -

Australian Conservation Foundation

SUBMISSION NO. 8 TT on 12 March 2013 Australian Conservation Foundation submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties on the Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the United Arab Emirates on Co- operation in the Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy May 2013 Introduction: The Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) is committed to inspiring people to achieve a healthy environment for all Australians. For nearly fifty years, we have worked with the community, business and government to protect, restore and sustain our environment. ACF welcomes this opportunity to comment on the Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the United Arab Emirates for Co-operation in the Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy. ACF has a long and continuing interest and active engagement with the Australian uranium sector and contests the assumptions under-lying the proposed treaty. ACF would welcome the opportunity to address this submission before the Committee. Nuclear safeguards Uranium is the principal material required for nuclear weapons. Successive Australian governments have attempted to maintain a distinction between civil and military end uses of Australian uranium exports, however this distinction is more psychological than real. No amount of safeguards can absolutely guarantee Australian uranium is used solely for peaceful purposes. According the former US Vice-President Al Gore, “in the eight years I served in the White House, every weapons proliferation issue we faced was linked with a civilian reactor program.”1 Energy Agency, 1993 Despite successive federal government assurances that bilateral safeguard agreements ensure peaceful uses of Australian uranium in nuclear power reactors, the fact remains that by exporting uranium for use in nuclear power programs to nuclear weapons states, other uranium supplies are free to be used for nuclear weapons programs.