Delaware Water Gap National Interstate 80 Pro- Recreation Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

. Hikes at The

Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area Hikes at the Gap Pennsylvania (Mt. Minsi) 4. Resort Point Spur to Appalachian Trail To Mt. Minsi PA from Kittatinny Point NJ This 1/4-mile blue-blazed trail begins across Turn right out of the visitor center parking lot. 1. Appalachian Trail South to Mt. Minsi (white blaze) Follow signs to Interstate 80 west over the river Route 611 from Resort Point Overlook (Toll), staying to the right. Take PA Exit 310 just The AT passes through the village of Delaware Water Gap (40.978171 -75.138205) -- cross carefully! -- after the toll. Follow signs to Rt. 611 south, turn to Mt. Minsi/Lake Lenape parking area (40.979754 and climbs up to Lake Lenape along a stream right at the light at the end of the ramp; turn left at -75.142189) off Mountain Rd.The trail then climbs 1-1/2 that once ran through the basement of the next light in the village; turn right 300 yards miles and 1,060 ft. to the top of Mt. Minsi, with views Kittatinny Hotel. (Look in the parking area for later at Deerhead Inn onto Mountain Rd. About 0.1 mile later turn left onto a paved road with an over the Gap and Mt. Tammany NJ. the round base of the hotel’s fountain.) At the Appalachian Trail (AT) marker to the parking top, turn left for views of the Gap along the AT area. Rock 2. Table Rock Spur southbound, or turn right for a short walk on Cores This 1/4-mile spur branches off the right of the Fire Road the AT northbound to Lake Lenape parking. -

NJGS Contracted with Greater New York City Through the Borough of Richmond President Cromwell, to Provide Water for 1835 Staten Island

UNEARTHING NEW JERSEY NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Vol. 5, No. 2 Summer 2009 Department of Environmental Protection MESSAGE FROM THE STATE GEOLOGIST A PLAN TO PLUNDER NEW JERSEY’S WATER This issue of Unearthing New Jersey continues the series of historic stories with Mark French’s article A Plan to Plunder New Jersey’s Water. This story concerns a plan by By Mark French the Hudson County Water Company and its myriad political allies to divert an enormous portion of the water resources of INTRODUCTION New Jersey to the City of New York. The scheme was driven At the turn of the 20th century, potable water in New by the desire for private gain at the expense of the citizens of Jersey was managed by private companies or municipalities New Jersey. Thanks to the swift action of the Legislature, the through special grants from the State Legislature or State Attorney General, the State Geologist and the highest certificates of incorporation granted by the State under the courts in the land, the Hudson County Water Company General Incorporation Law of 1875. Clamoring for oversight, plot was stymied setting a riparian rights precedent in the the citizenry and the Legislature tried to create a State process. Water Commission in 1894, but the effort was quashed by A second historic article, The New York-New Jersey Line water business interests and their friends in the Legislature. War by Ted Pallis, Mike Girard and Walt Marzulli discusses Companies were mostly free to traffic in water as they saw the geographic boundaries of New Jersey. -

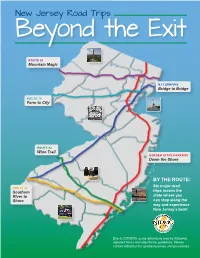

Beyond the Exit

New Jersey Road Trips Beyond the Exit ROUTE 80 Mountain Magic NJ TURNPIKE Bridge to Bridge ROUTE 78 Farm to City ROUTE 42 Wine Trail GARDEN STATE PARKWAY Down the Shore BY THE ROUTE: Six major road ROUTE 40 Southern trips across the River to state where you Shore can stop along the way and experience New Jersey’s best! Due to COVID19, some attractions may be following adjusted hours and attendance guidelines. Please contact attraction for updated policies and procedures. NJ TURNPIKE – Bridge to Bridge 1 PALISADES 8 GROUNDS 9 SIX FLAGS CLIFFS FOR SCULPTURE GREAT ADVENTURE 5 6 1 2 4 3 2 7 10 ADVENTURE NYC SKYLINE PRINCETON AQUARIUM 7 8 9 3 LIBERTY STATE 6 MEADOWLANDS 11 BATTLESHIP PARK/STATUE SPORTS COMPLEX NEW JERSEY 10 OF LIBERTY 11 4 LIBERTY 5 AMERICAN SCIENCE CENTER DREAM 1 PALISADES CLIFFS - The Palisades are among the most dramatic 7 PRINCETON - Princeton is a town in New Jersey, known for the Ivy geologic features in the vicinity of New York City, forming a canyon of the League Princeton University. The campus includes the Collegiate Hudson north of the George Washington Bridge, as well as providing a University Chapel and the broad collection of the Princeton University vista of the Manhattan skyline. They sit in the Newark Basin, a rift basin Art Museum. Other notable sites of the town are the Morven Museum located mostly in New Jersey. & Garden, an 18th-century mansion with period furnishings; Princeton Battlefield State Park, a Revolutionary War site; and the colonial Clarke NYC SKYLINE – Hudson County, NJ offers restaurants and hotels along 2 House Museum which exhibits historic weapons the Hudson River where visitors can view the iconic NYC Skyline – from rooftop dining to walk/ biking promenades. -

Delaware Water Gap U.S

National Park Service Delaware Water Gap U.S. Department of the Interior National Recreation Area Summer/Fall 2015 Guide to the Gap N A YEARS A T E I 50 1965-2015 R O A N N AL IO RECREAT Your National Park Celebrates 50 Years! The Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area was established by a park for the people. Today, visitors roam a landscape carved by uplift, Congress on September 1, 1965, to preserve the natural, culture, and scenic erosion, and glacial activity that is marked by hemlock and rhododendron- resources of the Delaware River Valley and provide opportunities for laced ravines, rumbling waterfalls, fertile floodplains and is rich with recreation, education, and enjoyment to the most densely populated region archaeological evidence and historic narratives. This haven for natural of the nation. Sprung out of the Tocks Island Dam controversy, the last and cultural stories is your place, your park, and we invite you to celebrate 50 years has solidified Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area as with us in 2015. The River, the Valley, and You . 2 Events. 4 Delaware River . 6 Park Trails . 8. Fees and Passes . 2 Park Map and Visitor Centers . 3 Are you curious about the natural and cultural Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area From ridgetop to riverside, vistas to ravines, Activities and Events in 2015 . 4 history of the area? Would you like to see includes nearly 40 miles of the free-flowing from easy to extreme, more than 100 Delaware River Water Trail . 6 artisans at work? Want to experience what it Middle Delaware River Scenic and Recreational miles of trail offer something for every mood. -

Vanderpoel-De Hooges-Post-Bradt

Chapter X: VanderPoel-De Hooges-Post-Bradt Last Revised: October 29, 2014 Ironically, we may know more about Abraham Vanderpool’s Dutch ancestors than we do about him. Because he was born in Albany, New York, we are able to forge a solid link between our Abraham born in 1709 (and, by extension, the Indiana Vanderpools) and the parent Vanderpool family of New York – and so the Dutch community there. Unusually rich information exists about the Vanderpool family and its associated families in New York, extending back to the earliest settlement of New Netherland (as it was called before the English conquest in 1664). Some of what we know comes from several published Vanderpool family histories, some from an excellent network of Vanderpool researchers, and some from documentary and scholarly sources, including the New Netherland Project in the New York State Archives. 1 Indeed, the Vanderpool line as a whole may be not only the lengthiest documented line in our entire family but the best- documented of all these lines as well. Because the half-century of Dutch dominion in what is now New York State and surrounding areas is not so well known today, it may be useful to profile here the major features of that era as a context for our discussion of the Vanderpools and their family 1 This heroic project is endeavoring to translate into English and make accessible all the surviving records (written in old Dutch, of course) relating to New Netherland. Some of the records from New Netherland were damaged or destroyed in a fire in the New York State Capitol Building in 1911. -

Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area

CULTURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT CRM VOLUME 25 NO. 3 2002 tie u^m Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Cultural Resources PUBLISHED BY THE CRM magazine's 25th anniversary year NATIONAL PARK SERVICE VOLUME 25 NO. 3 2002 Information for parks, Federal agencies, Contents ISSN 1068-4999 Indian tribes, States, local governments, and the private sector that promotes and maintains high standards for pre Saved from the Dam serving and managing cultural resources In the Beginning 3 Upper Delaware Valley Cottages— Thomas E. Solon A Simple Regional Dwelling Form . .27 DIRECTOR Kenneth F. Sandri Fran R Mainella From "Wreck-reation" to Recreation Area— Camp Staff Breathes New Life ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR CULTURAL RESOURCE STEWARDSHIP A Superintendent's Perspective 4 into Old Cabin 29 AND PARTNERSHIPS Bill Laitner Chuck Evertz and Katherine H. Stevenson Larry J. Smotroff In-Tocks-icated—The Tocks Island MANAGING EDITOR Dam Project 5 Preserving and Interpreting Historic John Robbins Richard C. Albert Houses—VIPs Show the Way 31 EDITOR Leonard R. Peck Sue Waldron "The Minisink"—A Chronicle of the Upper Delaware Valley 7 Yesterday and Today—Planting ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dennis Bertland for Tomorrow 33 Janice C. McCoy Larry Hilaire GUEST EDITOR Saving a Few, Before Losing Them All— Thomas E. Solon A Strategy for Setting Priorities 9 Searching for the Old Mine Road ... .35 Zehra Osman Alicia C. Batko ADVISORS David Andrews Countrysides Lost and Found— Bit by Bit—Curation in a National Editor, NPS Joan Bacharach Discovering Cultural Landscapes 14 Recreation Area 36 Curator, NPS Hugh C. -

The Dutch Mines: Fact Or Myth? <

U.S. Dept. of the Interior National Park Service . Spanning the Gap The Dutch Mines: Fact or Myth? < The newsletter of Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area Vol. 10 No. 2 Summer 1988 Did the Dutch mine in this area? Historic Mining at Pahaquarry Local historians credit the Dutch with starting the mining operations in the valley. The Dutch, it is said, sent exploration parties south searching for valuable minerals out from Dutch settlement at Esopus on the Hudson River (near Kingston NY), which was settled in 1614. The green malachite visible in the rock here indicated the possible presence of copper sulfide, or chalocite, an ore of interest. The story continues, to claim that 104-mile Old Mine The Copper Mill around 1905. Road was constructed to haul ore from the area of Its foundations were later Pahaquarry Copper Mines to Esopus for shipment to used for a boy scout mess Holland. From there it could be shipped down the hall. Hudson and to Holland. The story seems to have started with publication of the Preston Letters in Hazard's Register in 1828. The letters tell about Hazard's trip in 1787 to the area and the stories he heard from local elders. He relates the journey of Thomas Penn's surveyors in 1730, who came here to survey previous claims. Preston wrote the mines had not been operated for some time, as the entrances were much overgrown Incline plane at the Copper with brush in 1787. Mines. The copper ore at Pahaquarry is of very poor grade and is But what is the evidence? very diffuse in the rock. -

The Role of Inlets in Piping Plover Nest Site Selection in New Jersey 1987-2007 45 Christina L

Birds Volume XXXV, Number 3 – December 2008 through February 2009 Changes from the Fiftieth Suppleument of the AOU Checklist 44 Don Freiday The Role of Inlets in Piping Plover Nest Site Selection in New Jersey 1987-2007 45 Christina L. Kisiel The Winter 2008-2009 Incursion of Rough-legged Hawks (Buteo lagopus) in New Jersey 52 Michael Britt WintER 2008 FIELD NotEs 57 50 Years Ago 72 Don Freiday Changes from the Fiftieth Supplement to the AOU Checklist by DON FREIDay n the recent past, “they” split Solitary Vireo into two separate species. The original names created for Blue-headed, Plumbeous, and Cassin’s Vireos. them have been deemed cumbersome by the AOU I “They” split the towhees, separating Rufous-sided committee. Now we have a shot at getting their full Editor, Towhee into Eastern Towhee and Spotted Towhee. names out of our mouths before they disappear into New Jersey Birds “They” seem to exist in part to support field guide the grass again! Don Freiday publishers, who must publish updated guides with Editor, Regional revised names and newly elevated species. Birders Our tanagers are really cardinals: tanager genus Reports often wonder, “Who are ‘They,’ anyway?” Piranga has been moved from the Thraupidae to Scott Barnes “They” are the “American Ornithologists’ Union the Cardinalidae Contributors Committee on Classification and Nomenclature - This change, which for NJ birders affects Summer Michael Britt Don Freiday North and Middle America,” and they have recently Tanager, Scarlet Tanager, and Western Tanager, has Christina L. Kisiel published a new supplement to the Check-list of been expected for several years. -

Birding Eastern North America 2016

Birding Eastern North America 2016 I had birded the USA three times before (Washington State, Florida and Arizona), but this time I decided to take my wife and two sons (13 and 10) with me. We started in New York then travelled through New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York State to Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada and back. Ring-billed Gull, Niagara Falls Northern Cardinal, Hamilton, Ontario New York After having arrived at Newark yesterday evening on Wednesday April 27th (picking up our rental car at the airport) I left our Holiday Inn hotel at 6 am for an early morning walk through suburban Hasbrouck Heights, New Jersey. A singing Northern Mockingbird was the first bird I saw, soon followed by Mourning Doves, lots of American Robins and a singing Song Sparrow. When the neighborhood got greener and the gardens bigger, White-throated Sparrows and Blue Jays appeared. I did not have too much trouble putting names to the bird sounds around me, finding Northern Cardinals, House Finches and Common Grackles, but chasing the call of what turned out to be a male Brown- headed Cowbird took a bit too much birding time. Four loud Northern Flickers and the first of many Downy Woodpeckers frequented a big tree that also hosted my first Myrtle Warbler of the trip. Ruby-crowned Kinglets were surprisingly common, one sycamore lined street produced at least four. A small piece of roadside wasteland had a pair of Killdeer with small young running around. After breakfast a hotel shuttle van took us to the bus stop where local bus 163 was waiting for us. -

A History of Millburn Township Ebook

A History of Millburn Township eBook A History of Millburn Township »» by Marian Meisner Jointly published by the Millburn/Short Hills Historical Society and the Millburn Free Public Library. Copyright, July 5, 2002. file:///c|/ebook/main.htm9/3/2004 6:40:37 PM content TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Before the Beginning - Millburn in Geological Times II. The First Inhabitants of Millburn III. The Country Before Settlement IV. The First English Settlements in Jersey V. The Indian Deeds VI. The First Millburn Settlers and How They Lived VII. I See by the Papers VIII. The War Comes to Millburn IX. The War Leaves Millburn and Many Loose Ends are Gathered Up X. The Mills of Millburn XI. The Years Between the Revolution and the Coming of the Railroad XII. The Coming of the Railroad XIII. 1857-1870 XIV. The Short Hills and Wyoming Developments XV. The History of Millburn Public Schools XVI. A History of Independent Schools XVII. Millburn's Churches XVIII. Growing Up file:///c|/ebook/toc.htm (1 of 2)9/3/2004 6:40:37 PM content XIX. Changing Times XX. Millburn Township Becomes a Centenarian XXI. 1958-1976 file:///c|/ebook/toc.htm (2 of 2)9/3/2004 6:40:37 PM content Contents CHAPTER I. BEFORE THE BEGINNING Chpt. 1 MILLBURN IN GEOLOGICAL TIMES Chpt. 2 Chpt. 3 The twelve square miles of earth which were bound together on March 20, Chpt. 4 1857, by the Legislature of the State of New Jersey, to form a body politic, thenceforth to be known as the Township of Millburn, is a fractional part of the Chpt. -

Geologic Trails in Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area

NYSGA 2010 Trip 1 - Epstein Delaware Water Gap, A Geology Classroom By Jack B. Epstein U.S. Geological Survey INTRODUCTION The Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area (DEWA) contains a rich geologic and cultural history within its 68,714 acre boundary. Following the border between New Jersey and Pennsylvania, the Delaware River has cut a magnificent gorge through Kittatinny Mountain, the Delaware Water Gap, to which all other gaps in the Appalachian Mountains have been compared. Proximity to many institutions of learning in this densely populated area of the northeastern United States (Fig. 1) makes DEWA an ideal locality to study the geology of this part of the Appalachian Mountains. This one- day field trip comprises an overview discussion of structure, stratigraphy, geomorphology, and glacial geology within the gap. It will be highlighted by hiking a choice of several trails with geologic guides, ranging from gentle to difficult. It is hoped that the ―professional‖ discussions at the stops, loaded with typical geologic jargon, can be translated into simple language that can be understood and assimilated by earth science students along the trails. This trip is mainly targeted for earth science educators and for Pennsylvania geologists needing to meet state-mandated education requirements for licensing professional geologists. The National Park Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, the New Jersey Geological Survey, and local schoolteachers had prepared ―The Many Faces of Delaware Water Gap: A Curriculum Guide for Grades 3–6‖ (Ferrence et al., 2003). Portions of this guide, ―The Many faces of Delaware Water Gap‖ appear as two appendices in this field guide and is also available by contacting the Park (http://www.nps.gov/dewa/forteachers/curriculummaterials.htm). -

Life and Death on the Old Mine Road 6.24.19

Old Calno School1 Life and Death on the Old Mine Road The consequences of the failed Tocks Island Dam Project By James Alexander Jr. Updated ©September 2021 This article is the first part of what has evolved into a major review of this government project which had unintended and painful results, now facing new challenges. For the full set of information, go here. Here is a land which many who live in New Jersey have never seen and in which as many more do not believe…. It is a land of crags and crowding precipices of the Kittatinny Ridge, of winding roads that were the paths of the Indians, of quiet and seldom-seen mountain lakes, of noisy brooks and flashing waterfalls, of hundred-year and even older houses at every turn…. Now and then, in spite of the improvements that have come even to the Old Mine Road, there is no more than a shelf in the side of the mountain…. Here, indeed, is a country that provides … a setting in which anything can 2 happen. 1 Pahaquarry and the Tocks Island Dam “We just got a call from the State House. You need to get up to Pahaquarry Township tomorrow evening.” That fall day back in the early seventies, managing a staff of wonderfully talented people providing management consulting services to New Jersey’s 567 municipalities and 21 counties, I asked two questions: “What’s up, and where is it?” The answer was short: “Senator Dumont asked us to send somebody. The town’s in trouble. There’s a meeting at the old Calno School somewhere above the Delaware Water Gap, along the Old Mine Road in Warren County.