Land and Conflict in Sudan 15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUDAN, YEAR 2018: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020

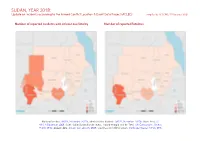

SUDAN, YEAR 2018: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Abyei Area: SS- NBS, 1 December 2008; South Sudan/Sudan border status, Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; incident data: ACLED, 22 February 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SUDAN, YEAR 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 293 124 283 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 151 99 697 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2018 2 Protests 150 4 9 Strategic developments 64 0 0 Methodology 3 Riots 54 12 26 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 30 16 28 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 742 255 1043 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2018 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). 2 SUDAN, YEAR 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Methodology this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Why a Minority Rights Approach to Conflict? the Case of Southern Sudan

briefing Why a minority rights approach to conflict? The case of Southern Sudan By Chris Chapman This briefing is aimed at decision-makers working on conflict management, peace-building, development and human rights in countries affected by conflict – whether they be officials of the government in question, humanitarian actors working for donor governments, inter- governmental organizations, local NGOs or international NGOs (the imperfect shorthand of ‘humanitarian actors’ will be used to cover all of these categories). The aim is to illustrate how the minority rights approach can be useful to the work of humanitarian actors in any conflict situation – whether it be aid distribution in a refugee camp, a reformed police force, or a new national education curriculum. For this purpose, the briefing examines the specific case of Southern Sudan. Conflict management requires a holistic approach that addresses all the causes of conflict, and the minority rights approach does not mean addressing only this aspect of conflict. However research carried out by Minority Rights Group International (MRG) has shown that governments and external actors often fail to understand the role that minority rights plays in both the origin and resolution of identity-based conflicts.1 Minority rights provides a framework for humanitarian actors to analyze, understand and address many of the complex issues behind the conflict, and if utilized by the Government of South Sudan (GoSS), can help to build peace based on the accommodation of diversity, through providing all communities with a political voice and equal opportunities to access resources. Southern Sudan provides a complex and demanding case A woman attends a peace conference between the Nuer and Dinka tribes study. -

SUDAN Price Bulletin August 2021

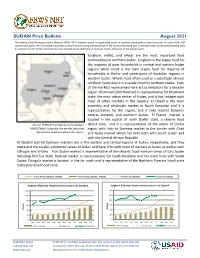

SUDAN Price Bulletin August 2021 The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) monitors trends in staple food prices in countries vulnerable to food insecurity. For each FEWS NET country and region, the Price Bulletin provides a set of charts showing monthly prices in the current marketing year in selected urban centers and allowing users to compare current trends with both five-year average prices, indicative of seasonal trends, and prices in the previous year. Sorghum, millet, and wheat are the most important food commodities in northern Sudan. Sorghum is the staple food for the majority of poor households in central and eastern Sudan regions while millet is the main staple food for majority of households in Darfur and some parts of Kordofan regions in western Sudan. Wheat most often used as a substitute all over northern Sudan but it is a staple food for northern states. Each of the markets represented here act as indicators for a broader region. Khartoum (Om Durman) is representative for Khartoum state, the main urban center of Sudan, and it has linkages with most of other markets in the country. El Obeid is the main assembly and wholesale market in North Kordofan and it is representative for the region, and it links market between central, western, and southern Sudan. El Fasher market is located in the capital of north Darfur state, a chronic food Source: FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges deficit area, and it is representative of the entire of Darfur FAMIS/FMoA, Sudan for the market data and region with links to Geneina market in the border with Chad information used to produce this report. -

Land in Gedarif State: Survival and Conflict

Land in Gedarif State: Survival and Conflict Anke van der Heul Radboud University Nijmegen Land in Gedarif State: Survival and Conflict An explorative research on the influence of group identity and the Sudanese state on the land conflicts in Gedarif State and the interaction of these factors on a local level. Anke van der Heul S0308048 Master ‘Conflicts, Territories and Identities’ CICAM & Human Geography, Radboud University Nijmegen Supervisor Dr. B. Bomert Radboud University Nijmegen December 2009 Cover painting by: Abdul Moniem Shglainiee (from Gedarif State) Land in Gedarif State: Survival and Conflict An explorative research on the influence of group identity and the Sudanese state on the land conflicts in Gedarif State and the interaction of these factors on a local level. Keywords East Sudan, Gedarif State, land conflict, group identity, poor governance, land tenure, state influence. Executive Summary Many African countries alike, Sudan has experienced a range of resource-based conflicts that often result in fierce competition between different clans or groups, in ethnic fighting or even in civil war. Although considerable research in the field of the Sudanese internal conflicts has concentrated on the conflict in Darfur and the Sudanese North-South conflict, rather less attention has been paid to the conflict in Eastern Sudan. Consequently this research aimed to explore the conflict in Eastern Sudan more in depth. More precisely, the focus of this research project has been narrowed down to Gedarif State and within the margins and the context of Gedarif State this research focused on land conflicts and the influence of group identity and the state. -

COUNTRY Food Security Update

SUDAN Food Security Outlook Update April 2017 Food security continues to deteriorate in South Kordofan and Jebel Marra KEY MESSAGES By March/April 2017, food insecurity among IDPs and poor residents in Food security outcomes, April to May 2017 SPLM-N areas of South Kordofan and new IDPs in parts of Jabal Mara in Darfur has already deteriorated to Crisis (IPC Phase 3) and is likely to deteriorate to Emergency (IPC Phase 4) by May/June through September 2017 due to displacement, restrictions on movement and trade flows, and limited access to normal livelihoods activities. Influxes of South Sudanese refugees into Sudan continued in March and April due to persistent conflict and severe acute food insecurity in South Sudan. As March 31, more than 85,000 South Sudanese refugees have arrived into Sudan since the beginning of 2017, raising total number arrived to nearly 380,000 South Sudanese refugees since the start of the conflict in December 2013. Following above-average 2016/17 harvests, staple food prices either remained stable or started increases between February and March, particularly in some arid areas of Darfur and Red Sea states, and South Source: FEWS NET Kordofan, which was affected by dryness in 2016. Prices remained on Projected food security outcomes, June to September average over 45 percent above their respective recent five-year 2017 average. Terms of trade (ToT) between livestock and staple foods prices have started to be in favor of cereal traders and producers since January 2017. CURRENT SITUATION Staple food prices either remained stable or started earlier than anticipated increases, particularly in the main arid and conflicted affected areas of Darfur, Red Sea and South Kordofan states between February and March. -

OSAC Crime & Safety Report

Sudan 2020 OSAC Crime & Safety Report This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Embassy in Khartoum. OSAC encourages travelers to use this report to gain baseline knowledge of security conditions in Sudan. For more in-depth information, review OSAC’s Sudan country page for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. Travel Advisory The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses Sudan at Level 3, indicating travelers should reconsider travel due to crime, terrorism, civil unrest, kidnapping, and armed conflict. Review OSAC’s report, Understanding the Consular Travel Advisory System. Overall Crime and Safety Situation A national state of emergency, which gives security forces greater powers of arrest, is in effect across the country. Detentions, including of foreigners, have occurred in different parts of the country, including in Khartoum. Demonstrations occur frequently and police response can be sudden and violent. Authorities may impose curfews with little or no warning. Penalties for violating curfews can include imprisonment. Crime Threats The U.S. Department of State has assessed Khartoum as being a MEDIUM-threat location for crime directed at or affecting official U.S. government interests. Crime rates increased over 2019, most likely connected to the deteriorating economic situation. Criminal activity is generally non-violent and non- confrontational. The Embassy received reports in 2019 of criminal targeting of UN personnel and other Westerners for car break-ins and other crimes of opportunity. -

Sudan COVID-19 Situation Update 2 July 2020

Sudan COVID-19 situation update 2 July 2020 Situation overview Map of COVID-19 response target population • As of 27 June, the Federal Ministry of Health has confirmed 9,257 cases and 572 associated fatalities. Sharg Jebel Marra Sheria MarshingNitega Kass Yassin Al Qoz Shattai Alwehda Ed Daein El Abassiya Nyala North Abu Restrictions on all public gatherings and movement remain in place, with curfews Karinka Adila Dilling Rashad • Kubum Bilel El dufusan Assalaya Habila Alslam imposed in some states as part of containment measures to limit the spread of the Greda El Ferdous Rehad Katyla Tules Abyei Reif Ashargi Heiban Dimso Abu Jubehia Buram Sunta Bahl Arab Abu Jabra Kadugli coronavirus. Um Dafug 14,000 Umm Durein Targeted EAST DARFUR Al Buram Talodi SOUTH DARFUR beneficiaries SOUTH Al Radoum KURDUFAN Closure of airports for both international and domestic flights has been extended until 113,700 • Targeted 30,000 beneficiaries Targeted 12 July 2020. This directive excludes repatriation flights, scheduled cargo flights, beneficiaries humanitarian aid and technical support flights, airlines operating in the oil fields, as well as Ed Damazine Ed Damazine evacuation flights for foreign nationals. Northern Red sea Al Tandamon Rosaries River Nile North Baw Geissan Darfur Khartoum Kassala Schools remain closed, affecting at least 8 million learners (figures from UNESCO). BLUE NILE • NorthNorth KurdufanKurdufan Al Jazirah West Al Qadarif El Kurmuk Darfur 73,459 West White Sennar Central Nile Targeted Darfur Kurdufan West beneficiaries South Kurdufan South Blue Darfur East Kurdufan Nile Impact on programming and operations Darfur • Containment measures taken to prevent the spread of coronavirus such as restrictions 9,257 on movement have slowed down the effective delivery of existing humanitarian response, COVID-19 cases confirmed as well as disrupting normal working. -

Food Security Status for the Household: a Case Study of Al

of Socia al lo rn m u ic o s J Bushara and Ibrahim, J Socialomics 2017, 6:4 Journal of Socialomics DOI: 10.1472/2167-0358.1000217 ISSN: 2167-0358 Case Study Open Access Food Security Status for the Household: A Case Study of Al-Qadarif State, Sudan (2016) Mohamed OA Bushara*and Ibrahim HH University of Gezira, WadMedani, Gezira State, Sudan *Corresponding author: Dr Mohamed OA Bushara. University of Gezira, WadMedani, Gezira State, Sudan, Tel: +249511826694; E-mail: [email protected] Rec date: April 20, 2017; Acc date: August 02, 2017; Pub date: August 15, 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Bushra MOA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Food security is under focused issue in Sudan and Al-Qadarif State is not apart from that. According to the integrated food security phases classification (IPC) report April 2015, about 60% of the population suffering from food insecurity in the state. This problem needs to be solved by a clear and sound policies and strategies. The main objective of this study is to evaluate the food security situation in the state, using a module concerning the demand side and to investigate and evaluate the Food Security and Nutrition (FSN) status in the state. To achieve this objective primary data were collected by the mean of questionnaires targeting house hold (394) sample size has been determined by using the Kerjcie and Morgan table, the household questionnaire was to determine the status of the food security within the state, using the USA. -

Sudan PVS Evaluation

OIE PVS Evaluation mission Sudan September Dr Cheryl French Dr Eric Fermet-Quinet, Dr Alberto Mancuso, Dr Maud Carron 2013 PVS Evaluation Report – Sudan – August 2014 The Republic of Sudan OIE PVS Evaluation – 2013 OIE PVS EVALUATION REPORT OF THE VETERINARY SERVICES OF The Republic of Sudan (September 8 – 20, 2013) Dr Cheryl French (Team Leader) Dr Eric Fermet-Quinet (Technical Expert) Dr Alberto Mancuso (Technical Expert) Dr Maud Carron (Observer/Facilitator) Disclaimer This evaluation has been conducted by an OIE PVS Evaluation Team authorised by the OIE. However, the views and the recommendations in this report are not necessarily those of the OIE. The results of the evaluation remain confidential between the evaluated country and the OIE until such time as the country agrees to release the report and states the terms of such release. World Organisation for Animal Health 12, rue de Prony F-75017 Paris, FRANCE The Republic of Sudan OIE PVS Evaluation – 2013 Table of contents PART I: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 I.1 Introduction 1 I.2 Key findings of the evaluation 2 I.2.A Human, physical and financial resources 2 I.2.B Technical authority and capability 3 I.2.C Interaction with interested parties 5 I.2.D Access to markets 5 I.3 Key recommendations 7 I.3.A Human, physical and financial resources 7 I.3.B Technical authority and capability 7 I.3.C Interaction with interested parties 8 I.3.D Access to markets 9 PART II: CONDUCT OF THE EVALUATION 11 II.1 OIE PVS Tool: method, objectives and scope of the evaluation 11 II.2 Country information (geography, -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: ICR2790 IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION AND RESULTS REPORT (TF-94475) ON A GRANT Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF US$6 MILLION TO THE REPUBLIC OF SUDAN FOR A ABYEI START UP EMERGENCY PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized June 13, 2013 Post Conflict and Social Development Practice Group (AFTCS) Sudan Country Department Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective June 13, 2013) Currency Unit = Sudanese Pounds 1.00 SDG = US$0.23 US$1.00 = 4.41 SDG FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AAA Abyei Area Administration ASEP Abyei Start-up Emergency Project CIFA Country Integrated Fiduciary Assessment CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement DA Designated Account DIPU Abyei Department of Infrastructure and Public Utilities EA Environmental Assessment ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework FMFA Financial Management Framework Agreement FPP Final Project Proposal GoNU Sudan Government of National Unity GoSS Government of South Sudan ICB International Competitive Bidding IDPs Internally Displaced People IPP Initial Project Proposal ISM Implementation Support Mission JAM Joint Assessment Mission LIB Limited International Bidding MA Monitoring Agent MDTF Multi Donor Trust Fund MOFNE Ministry of Finance and National Economy MOU Memorandum of Understanding MTR Mid-term Review MWMP Medical Waste Management Plan NCB National Competitive Bidding NCP National Congress Party NGO Non Governmental Organization OC -

Sudan, December 2004

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Sudan, December 2004 COUNTRY PROFILE: SUDAN December 2004 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of the Sudan (Jumhuriyat as-Sudan). Short Form: Sudan. Term for Citizen(s): Sudanese. Capital: Khartoum. Other Major Cities: Omdurman, Khartoum North, Port Click to Enlarge Image Sudan, Kassala, Al Ubayyid, and Nyala (according to decreasing size, 1993 census). Independence: Sudan gained independence from the United Kingdom and Egypt on January 1, 1956. Public Holidays: Sudan observes the following public holidays: Independence Day (January 1, 2004), Feast of the Sacrifice/Id al-Adha (February 1, 2004*), Islamic New Year (February 22, 2004*), Uprising Day, anniversary of 1985 coup (April 6, 2004), Coptic Easter Monday/Sham an-Nassim (April 12, 2004*), Birth of the Prophet/Mouloud (May 2, 2004*), Revolution Day (June 30, 2004), end of Ramadan/Id al-Fitr (November 14, 2004*), and Christmas (December 25, 2004). The asterisk indicates holidays with variable dates according to the Islamic or Coptic calendar. Flag: Sudan’s flag has three horizontal bands of red (top), white, and black with a green isosceles triangle based on the hoist side. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Click to Enlarge Image Prehistory and Early History: Northern Sudan was inhabited by hunting and gathering peoples by at least 60,000 years ago. These peoples had given way to pastoralists and probably agriculturalists at least by the fourth millennium B.C. Sudan’s subsequent culture and history have largely revolved around relations to the north with Egypt and to the south with tropical Africa, the Nile River forming a “bridge” through the Sahara Desert between the two. -

Dairy Quick Scan Sudan the Netherlands, October 2016

Report for: Rijksdienst voor Ondernemend Nederland Dairy quick scan Sudan The Netherlands, October 2016 THE FRIESIAN FOTO 1 The Friesian – Dairy Development Company Table of content Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Country profile ................................................................................................................................................. 8 2.1 Land features .......................................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Demographics ....................................................................................................................................... 11 2.3 Eastern Sudan ....................................................................................................................................... 11 2.4 Economics ............................................................................................................................................. 12 3. Dairy sector in Sudan ..................................................................................................................................... 13 3.1 General facts ........................................................................................................................................