Regional Indices of Socio-Economic and Health Inequalities: a Tool for Public Health Programming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It001e00020532 Bt 6,6 Vocabolo Case Sparse 0

CODICE POD TIPO FORNITURA EE POTENZA IMPEGNATA INDIRIZZO SITO FORNITURA COMUNE FORNITURA IT001E00020532 BT 6,6 VOCABOLO CASE SPARSE 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020533 BT 3 VOCABOLO CASE SPARSE 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020534 BT 6 VOCABOLO CASE SPARSE 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020535 BT 11 VIA DEI GELSI 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020536 BT 6 VIA MADONNA DELLA NEVE 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020537 BT 22 VIA ROMA 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020538 BT 22 VOCABOLO SELVE 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020539 BT 6 VIA COL DI LANA 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020540 BT 6 VIALE EUROPA 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020541 BT 16,5 VIALE EUROPA 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020542 BT 6 VIALE J.F. KENNEDY 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020543 BT 11 LOCALITA' PIAN DI CASTELLO 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020544 BT 6 LOCALITA' RADICE 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020545 BT 6 VIALE UMBERTO I 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020546 BT 1,65 LOCALITA' PIANO MONTE 0 - 05030 - POLINO (TR) [IT] POLINO IT001E00020547 BT 63 VIA PROV. ARR. POLINO 0 - 05030 - POLINO (TR) [IT] POLINO IT001E00020548 MT 53 VIA PROV. ARR. POLINO 0 - 05030 - POLINO (TR) [IT] POLINO IT001E00020552 BT 22 LOCALITA' FAVAZZANO -

Crowdsourcing Memories and Artefacts to Reconstruct Italian Cinema History: Micro- Histories of Small-Town Exhibition in the 1950S

. Volume 16, Issue 1 May 2019 Crowdsourcing memories and artefacts to reconstruct Italian cinema history: Micro- histories of small-town exhibition in the 1950s Daniela Treveri Gennari, Oxford Brookes University, UK Sarah Culhane, Maynooth University, Ireland Abstract: In the mid-1950s, cinema was Italy’s second most important industry (Wagstaff 1995: 97). At its peak, the country’s exhibition circuit boasted some 8,000 cinemas (Quaglietti 1980). Despite the important role that cinema played within the social, cultural and economic fabric of 1950s Italy, we know relatively little about the workings of the distribution and exhibition networks across urban and rural contexts. We know even less about the individuals whose working lives and family businesses depended on the cinema industry. This article uses micro-history case studies to explore some of the broader questions associated with the history of film exhibition and distribution in 1950s Italy. We use both the oral history testimonies collected during the AHRC-funded Italian Cinema Audiences project (www.italiancinemaaudiences.org) and the crowdsourced digital artefacts donated by members of the general public during the creation of CineRicordi (www.cinericordi.it), an online archive that allows users to explore the history of Italian cinema-going. Building on the oral histories gathered for the Italian Cinema Audiences project, this archive integrates the video-interviews of 160 ordinary cinema-goers with public and private archival materials. With this article, we aim to explore the ‘relationship between image, oral narrative, and memory’ (Freund and Thomson 2011: 4), where - as Freund and Thomson describe – ‘words invest photographs with meaning’ (2011: 5). -

Rankings Province of Terni

9/27/2021 Maps, analysis and statistics about the resident population Demographic balance, population and familiy trends, age classes and average age, civil status and foreigners Skip Navigation Links ITALIA / Umbria / Province of Terni Powered by Page 1 L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH ITALIA Municipalities Powered by Page 2 Acquasparta Stroll up beside >> L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Fabro AdminstatAllerona logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Ferentillo Alviano ITALIA Ficulle Amelia Giove Arrone Guardea Attigliano Lugnano in Avigliano Teverina Umbro Montecastrilli Baschi Montecchio Calvi dell'Umbria Montefranco Castel Giorgio Montegabbione Castel Viscardo Monteleone d'Orvieto Narni Orvieto Otricoli Parrano Penna in Teverina Polino Porano San Gemini San Venanzo Stroncone Terni Provinces PERUGIA TERNI Regions Powered by Page 3 Abruzzo Liguria L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin AdminstatBasilicata logo Lombardia DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Calabria MarcheITALIA Campania Molise Città del Piemonte Vaticano Puglia Emilia-Romagna Repubblica di Friuli-Venezia San Marino Giulia Sardegna Lazio Sicilia Toscana Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol Umbria Valle d'Aosta/Vallée d'Aoste Veneto Province of Terni Territorial extension of Province of TERNI and related population density, population per gender and number of households, average age and incidence of foreigners TERRITORY DEMOGRAPHIC DATA (YEAR 2019) Region Umbria Sign TR Inhabitants (N.) 223,455 Municipality capital Terni Families (N.) 103,488 Municipalities in Males (%) 48.0 33 Province Females (%) 52.0 Surface (Km2) 2,127.23 Foreigners (%) 10.1 Population density 105.0 (Inhabitants/Kmq) Powered by Page 4 Average age L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin 48.0 (years) Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Average annualITALIA variation -0.63 (2014/2019) MALES, FEMALES AND DEMOGRAPHIC BALANCE FOREIGNERS INCIDENCE (YEAR 2019) (YEAR 2019) Balance of nature [1], Migrat. -

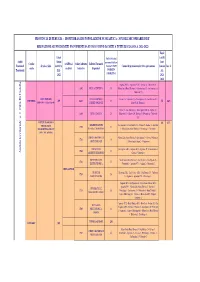

REPORT STUDENTI ISCRITTI DA COMUNI DIVERSI A.S 2021-2022.Pdf

PROVINCIA DI PERUGIA - MONITORAGGIO POPOLAZIONE SCOLASTICA - SCUOLE SECONDARIE DI II° RILEVAZIONE ALUNNI ISCRITTI PROVENIENTI DA FUORI COMUNE (ISCRITTI A TUTTE LE CLASSI A.S. 2021-2022) Totale Totale TOTALE Iscritti iscritti Ambiti Alunni fuori Ccodice Sedi/Plessi Codice indirizzo Indirizzi Formativi provenienti da fuori Funzionali Scuola e Sede iscritti AS Comune X OGNI Comuni di provenienza/iscritti x ogni comune Comune Inc. % scuola scoalstici formativo frequentati Territoriali 2021- INDIRIZZO A.S. 2022 FORMATIVO 2021- 2022 Anghiari AR (1) - Apecchio PU (2) - Citerna (3) - Monterchi (2) - LI02 LICEO SCIENTIFICO 23 Monta Santa Maria Tiberina (3) - San Giustino (7) - San Sepolcro (2)- Umbertide (3) LICEO "PLINIO IL LICEO SCIENTIFICO Citerna (1) - Umbertide (13) - San Sepolcro (1) - San Giustino (2) - PGPC05000A 499 L103 19 71 14% GIOVANE" - Città di Castello SCIENZE APPLICATE Monte S. M. Tiberina (2) Citerna (3) - San Giustino (4) - San Sepolcro AR (4)- Anghiari (1) - LI01 LICEO CLASSICO 29 Monterchi (1) - Monte S.M. Tiberina (1) - Perugia (2) - Umbertide (13) ISTITUTO ECONOMICO 425 45% AMMINISTRAZIONE San Giustino 11 - San Sepolcro 11 - Citerna 6 - Anghiari 2 - Apecchio TECNOLOGICO IT01 41 "FRANCHETTI-SALVIANI" FINANZA E MARKETING 1 - Monte Santa Maria Tiberina 5 - Pietralunga 1 -Umbertide 4 CITTA' DI CASTELLO CHIMICA MATERIALI E Monte Santa Maria Tiberina 2 - San Giustino 2 - Citerna 2 -Monterchi IT16 10 BIOTECNOLOGIE 1 - Pieve Santo Stefano 2 - Verghereto 1 COSTRUZIONI San Sepolcro AR 1- Anghiari AR 2 - Apecchio PU 2- San Giustino -

Spostamento Di Comuni Dalla Circoscrizione Di Tribunale Di Terni a Quella Di Perugia A.C

Spostamento di comuni dalla circoscrizione di tribunale di Terni a quella di Perugia A.C. 2962 Dossier n° 474 - Schede di lettura 20 luglio 2016 Informazioni sugli atti di riferimento A.C. 2962 Titolo: Modifiche alla tabella A allegata all'ordinamento giudiziario, di cui al regio decreto 30 gennaio 1941, n. 12, relative alle circoscrizioni dei tribunali di Perugia e di Terni, e alla tabella A allegata alla legge 21 novembre 1991, n. 374, relative a uffici del giudice di pace compresi nelle medesime circoscrizioni Iniziativa: Parlamentare Primo firmatario: Verini Numero di articoli: 1 Date: presentazione: 17 marzo 2015 trasmissione alla Camera: 17 marzo 2015 assegnazione: 15 maggio 2015 Commissione competente : II Giustizia Sede: referente Pareri previsti: I , V e XI Contenuto La proposta di legge A.C. 2962 modifica le circoscrizioni di tribunale nella Corte d'appello di Perugia, spostando tre comuni umbri (Città della Pieve, Paciano e Piegaro) dal tribunale di Terni al tribunale di Perugia. Vengono inoltre riviste le circoscrizioni territoriali dei giudici di pace dei due circondari e viene dettata una disciplina transitoria. In sede di attuazione della legge dovranno essere conseguentemente modificate le piante organiche degli uffici giudiziari coinvolti, senza maggiori oneri per il bilancio dello Stato. Corte d'appello di Perugia: situazione attuale A seguito della riforma della geografia giudiziaria del 2012 (che ha comportato la soppressione di 30 tribunali e 220 sezioni distaccate di tribunale), la Corte d'appello di Perugia comprende -

Complessi Sportivi Nella Provincia Di Terni

CODICE TIPOLOGIA CODICE TIPOLOGIA COMUNE DENOMINAZIONE FRAZIONE INDIRIZZO CAP TELEFONO IMPIANTO SPAZIO CAMPO DI CALCIO " MASSIMO ALLERONA ALLERONA LOCALITA' CASELLA OSPEDALE 5011 030 CALCIO 030 CALCIO TARDIOLO" CAPOLUOGO ALLERONA ALLERONA IMPIANTI SPORTIVI VIA MADONNA DELL'ACQUA 5011 320 TENNIS 320 TENNIS CAPOLUOGO ALLERONA ALLERONA IMPIANTI SPORTIVI VIA MADONNA DELL'ACQUA 5011 060 BOCCE 060 BOCCE CAPOLUOGO 180 POLIVALENTI ALLERONA 180 POLIVALENTI ALL'APERTO O ALLERONA IMPIANTI SPORTIVI VIA MADONNA DELL'ACQUA 5011 CAPOLUOGO ALL'APERTO SEMPLICEMENTE COPERTI ALLERONA CAMPO DA TENNIS ALLERONA SCALO ALLERONA SCALO VIA S.ABBONDIO 5011 320 TENNIS 320 TENNIS ALLERONA CAMPO DI CALCIO ALLERONA SCALO LOCALITA' FONDACCE 5011 030 CALCIO 030 CALCIO CAMPO DA CALCIO FRAZIONE DI AMELIA FORNOLE STRADA SAN SILVESTRO 5022 030 CALCIO 030 CALCIO FORNOLE CAMPO SPORTIVO FRAZIONE DI AMELIA MACCHIE FRAZIONE DI MACCHIE 5022 030 CALCIO 030 CALCIO MACCHIE CAMPO DA CALCIO FRAZIONE PORCHIANO FRAZIONE DI PORCHIANO DEL AMELIA 5022 030 CALCIO 030 CALCIO PORCHIANO DEL MONTE DELMONTE MONTE CAMPO SPORTIVO FRAZIONE DI AMELIA SAMBUCETOLE FRAZIONE DI SAMBUCETOLE 5022 030 CALCIO 030 CALCIO SAMBUCETOLE 012 ATLETICA IMPIANTO SPORTIVO "ALDO LOC. PATICCHI - STRADA DELLE 020 CALCIO E AMELIA 5022 LEGGERA -PISTE PAGLIARICCI" TORRI ATLETICA LEGGERA ANULARI IMPIANTO SPORTIVO "ALDO LOC. PATICCHI - STRADA DELLE AMELIA 5022 320 TENNIS 320 TENNIS PAGLIARICCI" TORRI IMPIANTO SPORTIVO "ALDO LOC. PATICCHI - STRADA DELLE AMELIA 5022 320 TENNIS 320 TENNIS PAGLIARICCI" TORRI IMPIANTO SPORTIVO "ALDO LOC. PATICCHI - STRADA DELLE 040 CALCETTO AMELIA 5022 040 CALCETTO PAGLIARICCI" TORRI (CALCIO A 5) IMPIANTO SPORTIVO "ALDO LOC. PATICCHI - STRADA DELLE AMELIA 5022 190 PALESTRE 190 PALESTRE PAGLIARICCI" TORRI IMPIANTO SPORTIVO "ALDO LOC. -

Ficulle 346 0940596 B

Telefono Nome Indirizzo ambulatorio Indirizzo ambulatorio secondario cellulare A Alesse Paola Via Nuova - Ficulle 346 0940596 B Piazza Olona, 28 Orvieto Bacchio Marco Via Cimanente, 4 Orvieto 346 0797102 Via Degli Eucalipti 45 Orvieto Vic. Pecorelli I, 8 - Biagioli Stefano Via Marconi N.5 Porano 346 0940565 Orvieto Via Degli Eucalipti, 24 - Borri Gilberto Via Della Costituente, 6 Orvieto 346 0940767 Orvieto C Via S. Quasimodo, 13 - Capini Arnaldo Via Degli Orti - Fabro 346 0941007 Fabro Scalo Caprini Michele Via Marconi, 5 - Porano 346 0421020 Loc. Colonnetta - Orvieto Cavagnaro Mario Via Marconi, 5 - Porano 346 0941003 Prodo Orvieto Via Della Costituente Orvieto P.zza Monte Rosa 7, Via Degli Eucalipti Ciconia - Cecchetti Luciana 346 0940785 Orvieto Scalo Orvieto Piazza Olona Sferracavallo Ceccolini Via Roma Nuova, 2 - 346 0940793 Gianfranco Castelgiorgio D G Piazza Cahen, 8/B - Gazzurra Stefano Via Monte Nibbio Orvieto 346 0940975 Orvieto Via Postierla, 10/A - Gioiosi Ugo 346 0941115 Orvieto Via del Gioco 5 - Gazzaneo Nicola Montecchio Grasselli Isauro P.zza Italia, 16 - Baschi Via Risorgimento Baschi 346 0941017 L Lisei Marco Claudio Via Della Libertà - Piazza Attilio Lupi - Allerona 346 0940680 Allerona Vicolo della Costa Castel Viscardo Frazione Faiolo Montegabbione Via Matteotti, 3 - Lucacchioni Tiziana Frazione Montegiove 346 0940644 Montegabbione Montegabbione M Via della Costituente, 6 - Marini Claudia 346 0940940 Orvieto Vic. della Pace, 25/C - Piazza Del Commercio - Orvieto Marziantonio Luigi 346 0941108 Orvieto Via Degli Eucalipti, -

Clicca Qui Per Ottenere L'intero Albo In

COLLEGIO PROVINCIALE DEI GEOMETRI E GEOMETRI LAUREATI DI TERNI ELENCO DEI GEOMETRI ISCRITTI ALL'ALBO PROFESSIONALE ANNO 2021 Sede: TERNI - Via C. Guglielmi n.29 - Tel - 0744/422.689 FAX 0744/426.086 e-mail: [email protected] - PEC: [email protected] SEDE DEL COLLEGIO: VIA CARLO GUGLIELMI 29 - 05100 TERNI TELEFONO - 0744/422689 - FAX 0744/426086 E-MAIL [email protected] PEC [email protected] CONSIGLIO DEL COLLEGIO eletto ai sensi del D.L.1t. 23.11.1944, n.382 e s.m. e i.. (In carica per il quadriennio 2018/2022) Presidente geom. Alberto Diomedi Segretario geom. Daniela Spaccini Tesoriere geom. Roberto Riommi Consiglieri geom. Luca Baciarello geom. Massimiliano Fancello geom. Daniela Figus geom. Stefano Fontanella geom. Marco Rondinelli geom. Luca Vergaro *************** CONSIGLIO NAZIONALE GEOMETRI E GEOMETRI LAUREATI Sede: P.zza Colonna n.361-00187 ROMA Presidente geom. Maurizio SAVONCELLI Vicepresidente geom. Ezio PIANTEDOSI Segretario geom. Enrico RISPOLI Consiglieri geom. Antonio Mario ACQUAVIVA geom. Luca BINI geom. Paolo BISCARO geom. Pierpaolo GIOVANNINI geom. Pietro LUCCHESI geom. Paolo NICOLOSI geom. Bernardino ROMITI geom. Livio SPINELLI *************** CASSA ITALIANA DI PREVIDENZA ED ASSISTENZA A FAVORE DEI GEOMETRI LIBERI PROFESSIONISTI Sede: ROMA - LUNGOTEVERE A. DA BRESCIA, 4 - TEL. 06/326861 CONSIGLIO DI AMMINISTRAZIONE Presidente geom. Diego Buono Vice Presidente geom. Renato Ferrari Consiglieri geom. Gianni Bruni geom. Carlo Cecchetelli geom. Cristiano Cremoli geom. Francesco Di Leo geom. Carmelo Garofalo geom. Massimo Magli geom. Carlo Papi geom. Vincenzo Paviato geom. Ilario Tesio GIUNTA ESECUTIVA Presidente geom. Diego Buono Vice Presidente geom. Renato Ferrari Componenti geom. Carlo Cecchetelli geom. Carmelo Garofalo geom. -

Diapositiva 1

Landscape studies Arch. Donatella Venti, elaborazioni Dott. Agr. F. Botti, Arch.tti C. Bagnetti, R. Amato, M.P. La Pegna The delimitation of the investigation area: • is based on PTCP (Territorial Plan of Provincial coordination) maps and considerations • passes through the examination of different landscape scales • begins by analysing the administrative limits and ends with the individuation of landscape units Umbria Region The Province of Terni City of Terni Territorial limits Landscape systems “Centrale Umbra” The valley of Terni and Narni •We have decided to focus on two different territorial limits: the “Centrale Umbra” and the Terni and Narni valley; in relation to the second case, we have analysed only two municipalities: Terni and Narni. •The two territorial limits involve three different landscape systems Landscape units The “Centrale Umbra” The valley of Terni and Narni •In relation to the “Centrale Umbra”, we have considered all the different landscape units which are included in PTCP, whereas, in regard to the valley of Terni and Narni, we have considered just the landscape units in contact with the Nera river. •The two territorial limits are really different: the valley described above is interested by a river landscape rich in industries and with an high concentration of constructions/buildings; the “Centrale Umbra” is a typical rural area. How did we obtain the different landscape units? A case of study: the territorial limit of the „Centrale Umbra‟ The territorial limit of the “Centrale Umbra” involves 4 municipalities We have divided this territorial ambit (limit) in two different parts. In relation to each one of them, we have organized a group of study and a critical mass which has involved different types of stakeholders 1 2 3 Basically the landscape units derived from the overlay (overlapping) of different maps: geological (1), vegetation (2), land-use (3) and also others as hidrology, soil consumption…. -

Andrea Brusaferro Curriculum Vitae

ANDREA BRUSAFERRO CURRICULUM VITAE Data details Education Occupation Scientific research Wildlife management Impact assessments Consultancy and organitations Teaching activities Conferences Languages and software Publications Brusaferro Andrea Curriculum Vitae DATA DETAILS Date of birth : September 12, 1965 Birthplace : MILANO (MI) Tax code : BRS NDR 65P12 F205O Professional activities : Research and Experimental Development in Natural Sciences VAT number : 01549610432 Residence : Fraz MERGNANO S.SAVINO n.8 - 62032 CAMERINO (MC) Marital Status : MARRIED Sons : ONE Phone : +39 0737 644372 / +39 327 2896687 E-mail : [email protected] and [email protected] Military Service : July 1990 - June 1991 (Appointed as a radio operator) Foreign Language : English (written and spoken) EDUCATION 1979 - 1984 High School "Leonardo da Vinci" Civitanova Marche (MC) o Scientific maturity. o Vote 46/60 1985 - 1990 University of Camerino, Camerino (MC) o Degree in Natural Sciences. o 110/110 cum laude . o Thesis: "Morphology of the facial region of the Merops apiaster (Aves, Coraciiformes, Meropidae)" o Teacher Guidae: Prof. Simonetta AM. 1991 - 1994 University of Camerino, Camerino (MC) o PhD in Molecular and Cellular Biology "VI cycle”. o PhD thesis: "Comparative Morphology of the skull in Coraciiformes (Aves). o Teacher Guide: Prof. Simonetta AM. 2 Brusaferro Andrea Curriculum Vitae 1997 University of Rome "La Sapienza" Roma o Laboratory of geometric morphometry. o Topic: Analysis of the shape and size of organisms through the geometric morphometry. o Teacher: Prof. F.J. Rohlf 2006 University of Urbino "Carlo Bo" Urbino (PU) o Professional course. o Topic: Introduction to ArcView and ArcInfo for ArcGis rel. 9.x (basic and advanced course). o 32 hours o Teacher: Prof. -

Determinazione Dei Collegi Elettorali Uninominali E Plurinominali Della Camera Dei Deputati E Del Senato Della Repubblica

Determinazione dei collegi elettorali uninominali e plurinominali della Camera dei deputati e del Senato della Repubblica Decreto legislativo 12 dicembre 2017, n. 189 UMBRIA Gennaio 2018 SERVIZIO STUDI TEL. 06 6706-2451 - [email protected] - @SR_Studi Dossier n. 567/2/Umbria SERVIZIO STUDI Dipartimento Istituzioni Tel. 06 6760-9475 - [email protected] - @CD_istituzioni SERVIZIO STUDI Sezione Affari regionali Tel. 06 6760-9261 6760-3888 - [email protected] - @CD_istituzioni Atti del Governo n. 474/2/Umbria La redazione del presente dossier è stata curata dal Servizio Studi della Camera dei deputati La documentazione dei Servizi e degli Uffici del Senato della Repubblica e della Camera dei deputati è destinata alle esigenze di documentazione interna per l'attività degli organi parlamentari e dei parlamentari. Si declina ogni responsabilità per la loro eventuale utilizzazione o riproduzione per fini non consentiti dalla legge. I contenuti originali possono essere riprodotti, nel rispetto della legge, a condizione che sia citata la fonte. File: ac0760b_umbria.docx Umbria Cartografie Camera dei deputati Per la circoscrizione Umbria sono presentate le seguenti cartografie: Senato della Repubblica ‐ Circoscrizione Umbria, che mostra la ripartizione del territorio in 3 collegi uninominali. Per la regione Umbria sono presentate le seguenti cartografie: ‐ Regione Umbria, che mostra la ripartizione del territorio in 2 collegi uninominali. Per l’elezione della Camera dei deputati il territorio della regione Umbria costituisce un’unica circoscrizione, cui sono assegnati 9 seggi, di cui 3 uninominali. I 6 seggi assegnati con il metodo proporzionale sono attribuiti in un unico collegio plurinominale, il cui territorio coincide con quello della circoscrizione. Per l’elezione del Senato della Repubblica il territorio della regione Umbria costituisce un’unica circoscrizione regionale. -

I Borghi Più Belli D'italia

I Borghi più Belli d’Italia Il fascino dell’Italia nascosta UUmmbbrriiaa MAGICAL VILLAGE ENERGIZE FOR LIFE Tour of the villages and festivals Fireworks, Folklore, Art, Music and Fine Tasting I BORGHI PIÙ BELLI D’ITALIA is an BORGHI ITALIA TOUR NETWORK is the exclusive club that contains the Citerna exclusive TOUR OPERATOR of the Club of most beautiful villages of Italy. This Montone the Most Beautiful Villages of Italy - Anci Castiglione Corciano initiative arose from the need to del Lago S. Antonio and responsible of tourism activity and Torgiano Bettona Paciano Panicale Spello promote the great heritage of His - Deruta strategy. It turns the hudge Heritage of Monte Castello Bevagna di Vibio tory, Art, Culture, Environment and Montefalco Trevi art, culture, traditions, fine food and wine Traditions of small Italian towns Massa Martana Norcia and the beauties of natural environment Acquasparta Vallo di Nera which are, for the large part, ex - in a unique Italian tourist product, full of Lugnano San Gemini Arrone cluded from the flows of visitors in Teverina charm and rich in contents. Emotional and tourists. Giove Stroncone tourism and relationship tourism. UMBRIA, near Rome and Florence, is the region with the largest number of most beautiful villages of Italy: 24! It’s land of grapes and olives, that pro - duces, from ancient Roman times, fine wine and oil; it’s land of mystical abbeys: between St. Benedict, patron of Europe and St. Francis, patron of Italy. Umbria is land of peace. THE BORGO… The most beautiful “borghi” of Italy are enchanted places whose beauty, consolidated over the centuries, tran - scends our lives, whose squares, fortresses, castles, churches, palaces, towers, bell towers, landscapes, festivals, typical products, stories allows us to understand what really Italy is, beyond the rhetoric, the most beautiful country in the world.