Non-Native Plants and Wildlife in the Intermountain West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

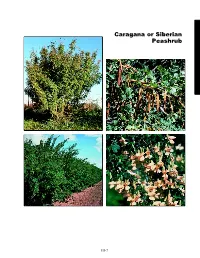

Caragana Or Siberian Peashrub

Caragana or Siberian Peashrub slide 5a 400% slide 5b 360% slide 5d slide 5c 360% 360% III-7 Caragana or Environmental Requirements Siberian Peashrub Soils Soil Texture - Adapted to a wide range of soils. (Caragana Soil pH - 5.0 to 8.0. arborescens) Windbreak Suitability Group - 1, 1K, 3, 4, 4C, 5, 6D, 6G, 8, 9C, 9L. General Description Cold Hardiness USDA Zone 2. Drought tolerant legume, long-lived, alkaline-tolerant, tall shrub native to Siberia. Ability to withstand extreme cold Water and dryness. Major windbreak species. Drought tolerant. Does not perform well on very wet or very dry sandy soils. Leaves and Buds Bud Arrangement - Alternate. Light Bud Color - Light brown, chaffy in nature. Full sun. Bud Size - 1/8 inch, weakly imbricate. Leaf Type and Shape - Pinnately-compound, 8 to 12 Uses leaflets per leaf. Conservation/Windbreaks Leaf Margins - Entire. Medium to tall shrub for farmstead and field windbreaks Leaf Surface - Pubescent in early spring, later glabrescent. and highway beautification. Leaf Length - 1½ to 3 inches; leaflets 1/2 to 1 inch. Wildlife Leaf Width - 1 to 2 inches; leaflets 1/3 to 2/3 inch. Used for nesting by several species of songbirds. Food Leaf Color - Light-green, become dark green in summer; source for hummingbirds. yellow fall color. Agroforestry Products Flowers and Fruits No known products. Flower Type - Small, pea-like. Flower Color - Showy yellow in spring. Urban/Recreational Fruit Type - Pod, with multiple seeds. Pods open with a Screening and border, ornamental flowers in spring. popping sound when ripe. Cultivated Varieties Fruit Color - Brown when mature. -

Legumes of the North-Central States: C

LEGUMES OF THE NORTH-CENTRAL STATES: C-ALEGEAE by Stanley Larson Welsh A Dissertation Submitted, to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Subject: Systematic Botany Approved: Signature was redacted for privacy. Signature was redacted for privacy. artment Signature was redacted for privacy. Dean of Graduat College Iowa State University Of Science and Technology Ames, Iowa I960 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORICAL ACCOUNT 3 MATERIALS AND METHODS 8 TAXONOMIC AND NOMENCLATURE TREATMENT 13 REFERENCES 158 APPENDIX A 176 APPENDIX B 202 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express his deep gratitude to Professor Duane Isely for assistance in the selection of the problem and for the con structive criticisms and words of encouragement offered throughout the course of this investigation. Support through the Iowa Agricultural Experiment Station and through the Industrial Science Research Institute made possible the field work required in this problem. Thanks are due to the curators of the many herbaria consulted during this investigation. Special thanks are due the curators of the Missouri Botanical Garden, U. S. National Museum, University of Minnesota, North Dakota Agricultural College, University of South Dakota, University of Nebraska, and University of Michigan. The cooperation of the librarians at Iowa State University is deeply appreciated. Special thanks are due Dr. G. B. Van Schaack of the Missouri Botanical Garden library. His enthusiastic assistance in finding rare botanical volumes has proved invaluable in the preparation of this paper. To the writer's wife, Stella, deepest appreciation is expressed. Her untiring devotion, work, and cooperation have made this work possible. -

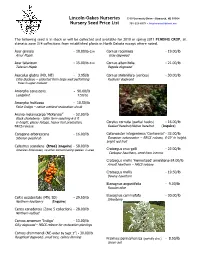

Nursery Price List

Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries 3310 University Drive • Bismarck, ND 58504 Nursery Seed Price List 701-223-8575 • [email protected] The following seed is in stock or will be collected and available for 2010 or spring 2011 PENDING CROP, all climatic zone 3/4 collections from established plants in North Dakota except where noted. Acer ginnala - 18.00/lb d.w Cornus racemosa - 19.00/lb Amur Maple Gray dogwood Acer tataricum - 15.00/lb d.w Cornus alternifolia - 21.00/lb Tatarian Maple Pagoda dogwood Aesculus glabra (ND, NE) - 3.95/lb Cornus stolonifera (sericea) - 30.00/lb Ohio Buckeye – collected from large well performing Redosier dogwood Trees in upper midwest Amorpha canescens - 90.00/lb Leadplant 7.50/oz Amorpha fruiticosa - 10.50/lb False Indigo – native wetland restoration shrub Aronia melanocarpa ‘McKenzie” - 52.00/lb Black chokeberry - taller form reaching 6-8 ft in height, glossy foliage, heavy fruit production, Corylus cornuta (partial husks) - 16.00/lb NRCS release Beaked hazelnut/Native hazelnut (Inquire) Caragana arborescens - 16.00/lb Cotoneaster integerrimus ‘Centennial’ - 32.00/lb Siberian peashrub European cotoneaster – NRCS release, 6-10’ in height, bright red fruit Celastrus scandens (true) (Inquire) - 58.00/lb American bittersweet, no other contaminating species in area Crataegus crus-galli - 22.00/lb Cockspur hawthorn, seed from inermis Crataegus mollis ‘Homestead’ arnoldiana-24.00/lb Arnold hawthorn – NRCS release Crataegus mollis - 19.50/lb Downy hawthorn Elaeagnus angustifolia - 9.00/lb Russian olive Elaeagnus commutata -

Appendix 6: Invasive Plant Species

USDA Forest Service Understanding i-Tree – Appendix 6: Invasive Plant Species APPENDIX 6 Invasive Plant Species The following is a list of invasive tree and shrub species by state that are included in i-Tree database (version 6). Each list of invasive species is followed by the reference of the source which were obtained circa 2014. Some of the Web addresses are no longer working; some have been relocated to alternative sites. State-specific invasive species lists will be updated in the future. Alabama Ailanthus altissima Lonicera japonica Poncirus trifoliate Albizia julibrissin Lonicera maackii Pyrus calleryana Ardisia crenata Lonicera morrowii Rosa bracteata Cinnamomum camphora Lonicera x bella Rosa multiflora Elaeagnus pungens Mahonia bealei Triadica sebifera Elaeagnus umbellata Melia azedarach Vernicia fordii Ligustrum japonicum Nandina domestica Wisteria sinensis Ligustrum lucidum Paulownia tomentosa Ligustrum sinense Polygonum cuspidatum Alabama Invasive Plant Council. 2007. 2007 plant list. Athens, GA: Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health, Southeast Exotic Pest Plant Council. http://www.se-eppc.org/ alabama/2007plantlist.pdf Alaska Alnus glutinosa Lonicera tatarica Sorbus aucuparia Caragana arborescens Polygonum cuspidatum Cytisus scoparius Prunus padus Alaska National Heritage Program. 2014. Non-Native plant data. Anchorage, AK: University of Alaska Anchorage. http://aknhp.uaa.alaska.edu/botany/akepic/non-native-plant-species- list/#content Arizona Alhagi maurorum Rhus lancea Tamarix parviflora Elaeagnus angustifolia Tamarix aphylla Tamarix ramosissima Euryops multifidus Tamarix chinensis Ulmus pumila Arizona Wildland Invasive Plant Working Group. 2005. Invasive non-native plants that threaten wildlands in Arizona. Phoenix, AZ: Southwest Vegetation Management Association https:// www.swvma.org/wp-content/uploads/Invasive-Non-Native-Plants-that-Threaten-Wildlands-in- Arizona.pdf (Accessed Sept 3. -

Effect of Diet on Larval Development, Adult Emergence and Fecundity of the Cinnabar Moth, Tyria Jacobaeae (L.) (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae)

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Sharon Diane Rose for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology presented on January 1978 Title: Effect of Diet on Larval Development, Adult Emergence and Fecundity of the Cinnabar Moth, Tyria jacobaeae (L.) (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae) Abstract approved: Redacted for privacy Dr. N. H. Anderson The cinnabar moth, Tyria jacobaeae (L.), is a biological control agent introduced in Oregon against the weed tansyragwort, Senecio jacobaea L. Goals of this research were: to determine if there exists significant variation in progeny of different cinnabar moth egg masses; to determine if (and how) rearing on different ragwort diets affects larval growth and subsequent adult emergence and fecundity;to investigate adult mating behavior; and to refine rearing techniques. Tansy ragwort diets used in this research include: leaves from first-year rosettes, leaves from second-year flowering plants, leaves from shade-grown plants, floral parts, and a mixture of the four preceeding diets. All larvae were reared in a growth chamber with photoperiod 12/12 and temperature 23.9° C. Mating pairs and ovipositing females were housed at photoperiod 14/10 and thermoperiod 23.90/100 C. Female and male pupae reared on the floral diet are significantly larger than those reared on the shade-leaf diet. Adults reared on the floral diet emerge significantly later than those rearedon the other four diets. Female moths reared on the floral, mixture and second-year leaf diets lay significantly more eggs than those rearedon the shade- leaf diet. Ranking diets by decreasing fecundity yields: floral, second-year leaves, mixture, first-year leaves, and shade-grown leaves. -

Feeding, Colonization and Impact of the Cinnabar Moth, Tyria Jacobaeae

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Jonathan W. Diehl for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology presented on May 20, 1988. Title: Feeding, Colonization and Impact of the Cinnabar Moth Tyria jacobaeae, on Senecio triangularisa Novel, Native Host Plant Abstract Redacted for privacy approved: Peter B. McEvoy I conducted field and laboratory studies to determine the impact of the cinnabar moth, Tvria jacobaeae L., on the native perennial herb, Senecio triangularis Hook. The cinnabar moth was introduced into Oregon in 1960 to control the noxious weed Senecio iacobaea L. and is now well established on both the native plant and the weed in Oregon. My objectives were to determine the suitability of S. triangularis as a diet for the cinnabar moth, to estimate the frequency with which the moths colonize the native plant in the field, and to estimate the impact of larval feeding on the plant's survivorship and reproduction. Larvae successfully completed development on S. triangularis, but development time was longer, growth was slower, and pupae were lighter compared to performance on S. iacobaea. Cinnabar moth colonization and feeding damage were concentrated at one of the four study sites observed. Cinnabar moth defoliation results in a 3.9% reduction in seed viability and is inversely related to damage to seeds by native insects. I conclude that cinnabar moths commonly discover this native plant in the field, can establish and develop on it, and cause a small reduction in plant reproductive success. Feeding, Colonization and Impact of the Cinnabar Moth, Tvria iacobaeae, on Senecio triangularis, a Novel, Native Host Plant by Jonathan W. -

Habitat and Corridor Function of Rights- Of-Way Marcel P. Huijser & Anthony

233 CHAPTER 11: HABITAT AND CORRIDOR FUNCTION OF RIGHTS- OF-WAY MARCEL P. HUIJSER & ANTHONY P. CLEVENGER Western Transportation Institute – Montana State University, PO Box 174250, Bozeman, MT 59717-4250, USA. 1. Introduction Roads, railroads and traffic can negatively affect plants, animals and other species groups (see reviews in Forman & Alexander 1998; Spellerberg 1998; van der Grift 1999). Transportation induced habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, reduced habitat quality and increased animal mortality can lead to serious problems for certain species or species groups, especially if they also suffer from other human-related disturbances such as large scale intensive agriculture and urban sprawl (Mader 1984; Ewing et al. 2005). Some species may even face local or regional extinction. However, other species or species groups can benefit from the presence of transportation infrastructure. Depending on the species and the surrounding landscape, the right-of-way can provide an important habitat or their only remaining functional habitat in the surrounding area. Rights-of-way may also serve as corridors between key habitat patches. The habitat and corridor function of rights-of-way can help improve the population viability of meta-populations of certain species in fragmented landscapes. This chapter aims to illustrate the habitat and corridor function of rights-of-way. While our focus is on roads, we include some examples of ecological benefits of railroads and railroad rights-of-way. For this chapter we define the term “right-of-way” as the area between the edge of the road surface, which is usually asphalt, concrete or gravel, and the edge of the area that is not owned or managed by the transportation agency. -

Caragana Arborescens.Lam) Powdery Mildew Fungi in Green Plantations in the Capital City of Mongolia

Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. (2021). 8(6): 85-92 International Journal of Advanced Research in Biological Sciences ISSN: 2348-8069 www.ijarbs.com DOI: 10.22192/ijarbs Coden: IJARQG (USA) Volume 8, Issue 6 -2021 Research Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22192/ijarbs.2021.08.06.012 A Study on Identification of Peashrub (Caragana arborescens.Lam) Powdery Mildew Fungi in Green Plantations in the Capital City of Mongolia Tsend ITGEL1 Ph.D. Associate Professor, Laboratory of Forest Protection, Plant protection institute, Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar Zaisan -210153 Gantumur GANZUL2 Ph.D Student., Laboratory of Forest protection, Plant protection institute, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia Janchiv TEMUUJIN2 Ph.D. Student., Laboratory of Biotechnology, Plant protection institute, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia *Corresponding author: [email protected]/[email protected] Abstract This study is aimed at determining powdery mildew prevalence and disease severity index of Siberian peashrub (Caragana arborescens) in the woody-bush plantations in the capital city Ulaanbaatar of Mongolia. The shrubs were assessed for powdery mildew disease incidence and disease severity index. Also, we intended to identify the pathogenic fungi species. The survey was carried out in four different parks and one alley in Ulaanbaatar city. The leaf samples were collected from the diseased pea-shrubs from those places. The identification of fungi at the genus level was carried out by using macroscopic and microscopic examinations depending on the fruiting body-cleistothecia shape, appendages, asci, ascospores, and arrangement of ascospores. For the molecular identification of the isolated fungi at the species level, the extracted fungal DNA was amplified by PCR using specific internal transcribed spacer primer (ITS1/ITS4). -

Caragana, Also Known As Siberian Peashrub, Is a Member of the Fabaceae Or Pea Family

CARAGANA (Caragana arborescens) Description: Caragana, also known as Siberian peashrub, is a member of the Fabaceae or pea family. Caragana is a rapid-growing shrub or small tree that can reach 15 to 20 feet in height with a spread of 12 to 18 feet. The bark is smooth with prominent lenticels, green to grayish-brown in color, and somewhat shiny. Leaves are alternate or fascicled, evenly pinnate, petiolate, stipules spiny, and 1 1/2 to 3 inches long. Leaves are composed of 8 to 12 leaflets that are bright green in color, obovate to ellipticoblong shaped, 1/2 to 1 inch long, rounded at the apex, mucronate pubescent when young, and glabrescent as the tree matures. Twigs are green to grayish-brown, armed with weak paired spines at each node, angled to grooved, with buds that are grayish-brown and 1/4 inch long. Flowers are bright yellow in color, single or in clusters, and about 1/2 to 1 inch long. Fruit of the tree is a cylindrical pencil- shaped narrow pod that is 1 1/2 to 2 inches long, yellowish-green to brown in color, with 3 to 5 seeds. Seeds are dark brown, smooth, 1/8 to 1/4 of an inch in length, and 1/8 of an inch wide. Distribution and Habitat: Caragana is now generally located throughout the north-central part of the United States. The tree occurs on most well drained soils and is able to adapt to poor site conditions. Caragana is tolerant of infertile soils, alkaline soils, de-icing salt, cold winter temperatures, drought conditions and some shade. -

And the Ragwort Flea Beetle (Longitarsus Jacobaeae) on Ragwort (Senecio Jacobaea)

-44-sratit-E-irr :44U:::;4.4% Journal of Applied Ecology Combining the cinnabar moth (Tyriajacobaeae) and the 1992, 29, ragwort flea beetle (Longitarsus jacobaeae) for control 589-596 of ragwort (Seneciojacobaea): an experimental analysis R.R. JAMES, P.B. McEVOY and C.S. COX Department of Entomology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331-2907, USA Summary A field experiment tested the independent and combined effects of the cinnabar moth (Tvria jacobaeae) and the ragwort flea beetle (Longitarsus jacobaeae) on ragwort (Senecio jacobaea). These insect herbivores feed on different stages of the host-plant and at different times of the year and were introduced to North America as biological control agents. Flea beetles alone were found to reduce vegetative ragwort densities b y 95%, and flower production by 39%, as compared to plants in control plots. Damage by cinnabar moths was simulated by removing all leaves and capitula from generative plants, but plants were able to regenerate some of the foliage and flowers. The treatment ultimately reduced capitulum production by 77% and the number of achenes per capitulum by 15%. Flea beetle damage was found to reduce the ability of flowering plants to compensate for defoliation and defloration to the extent that capitulum production was reduced by 98% and no viable achenes were produced. 3. These findings support the strategy of introducing complementary enemies which attack different stages and at different times, thereby reducing the number of invulnerable life stage and temporal refuges for the host. Key-words: biological control, weeds, insects, single vs. multiple enemy introductions. Journal of Applied Ecology (1992) 29, 589-596 and after the introduction of biological control agents Introduction (Dodd 1940; Huffaker Kennett 1959; Hawkes In the practice of biological control, several different Johnson 1978; Cullen 1978; McEvoy 1985). -

Caragana Or Siberian Peashrub

Caragana or Siberian Peashrub slide 5a 400% slide 5b 360% slide 5d slide 5c 360% 360% III-7 Caragana or Environmental Requirements Siberian Peashrub Soils Soil Texture - Adapted to a wide range of soils. (Caragana Soil pH - 5.0 to 8.0. arborescens) Windbreak Suitability Group - 1, 1K, 3, 4, 4C, 5, 6D, 6G, 8, 9C, 9L. General Description Cold Hardiness USDA Zone 2. Drought tolerant legume, long-lived, alkaline-tolerant, tall shrub native to Siberia. Ability to withstand extreme cold Water and dryness. Major windbreak species. Drought tolerant. Does not perform well on very wet or very dry sandy soils. Leaves and Buds Bud Arrangement - Alternate. Light Bud Color - Light brown, chaffy in nature. Full sun. Bud Size - 1/8 inch, weakly imbricate. Leaf Type and Shape - Pinnately-compound, 8 to 12 Uses leaflets per leaf. Conservation/Windbreaks Leaf Margins - Entire. Medium to tall shrub for farmstead and field windbreaks Leaf Surface - Pubescent in early spring, later glabrescent. and highway beautification. Leaf Length - 1½ to 3 inches; leaflets 1/2 to 1 inch. Wildlife Leaf Width - 1 to 2 inches; leaflets 1/3 to 2/3 inch. Used for nesting by several species of songbirds. Food Leaf Color - Light-green, become dark green in summer; source for hummingbirds. yellow fall color. Agroforestry Products Flowers and Fruits No known products. Flower Type - Small, pea-like. Flower Color - Showy yellow in spring. Urban/Recreational Fruit Type - Pod, with multiple seeds. Pods open with a Screening and border, ornamental flowers in spring. popping sound when ripe. Cultivated Varieties Fruit Color - Brown when mature. -

Lepidoptera: Arctiidae), and Potential for Biological Control of Senecio Madagascariensis (Asteraceae) M

J. Appl. Entomol. Host range of Secusio extensa (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae), and potential for biological control of Senecio madagascariensis (Asteraceae) M. M. Ramadan1, K. T. Murai1 & T. Johnson2 1 State of Hawaii Department of Agriculture, Plant Pest Control Branch, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA 2 Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry, Pacific Southwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Volcano, Hawaii, USA Keywords Abstract Host range, Secusio extensa, Senecio madagascariensis Secusio extensa (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae) was evaluated as a potential bio- logical control agent for Madagascar fireweed, Senecio madagascariensis Correspondence (Asteraceae), which has invaded over 400 000 acres of rangeland in the Mohsen M. Ramadan (corresponding author), Hawaiian Islands and is toxic to cattle and horses. The moth was intro- State of Hawaii Department of Agriculture, duced from southeastern Madagascar into containment facilities in Plant Pest Control Branch, 1428 South King Hawaii, and host specificity tests were conducted on 71 endemic and Street, Honolulu, Hawaii 96814, USA. E-mail: [email protected] naturalized species (52 genera) in 12 tribes of Asteraceae and 17 species of non-Asteraceae including six native shrubs and trees considered key Received: September 15, 2009; accepted: components of Hawaiian ecosystems. No-choice feeding tests indicated April 6, 2010. that plant species of the tribe Senecioneae were suitable hosts with first instars completing development to adult stage on S. madagascariensis doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2010.01536.x (78.3%), Delairea odorata (66.1%), Senecio vulgaris (57.1%), Crassoceph- alum crepidioides (41.2%), and at significantly lower rates on Emilia fos- bergii (1.8%) and Erechtites hieracifolia (1.3%). A low rate of complete larval development also was observed on sunflower, Helianthus annuus (11.6%), in the tribe Heliantheae.