Haloperidol Is As Effective As Ondansetron for Preventing Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medications and Alcohol Craving

Medications and Alcohol Craving Robert M. Swift, M.D., Ph.D. The use of medications as an adjunct to alcoholism treatment is based on the premise that craving and other manifestations of alcoholism are mediated by neurobiological mechanisms. Three of the four medications approved in the United States or Europe for treating alcoholism are reported to reduce craving; these include naltrexone (ReVia™), acamprosate, and tiapride. The remaining medication, disulfiram (Antabuse®), may also possess some anticraving activity. Additional medications that have been investigated include ritanserin, which has not been shown to decrease craving or drinking levels in humans, and ondansetron, which shows promise for treating early onset alcoholics, who generally respond poorly to psychosocial treatment alone. Use of anticraving medications in combination (e.g., naltrexone plus acamprosate) may enhance their effectiveness. Future studies should address such issues as optimal dosing regimens and the development of strategies to enhance patient compliance. KEY WORDS: AOD (alcohol and other drug) craving; anti alcohol craving agents; alcohol withdrawal agents; drug therapy; neurobiological theory; alcohol cue; disulfiram; naltrexone; calcium acetylhomotaurinate; dopamine; serotonin uptake inhibitors; buspirone; treatment outcome; reinforcement; neurotransmitters; patient assessment; literature review riteria for defining alcoholism Results of craving research are often tions (i.e., pharmacotherapy) to improve vary widely. Most definitions difficult to interpret, -

Safety and Efficacy of a Continuous Infusion, Patient Controlled Anti

Bone Marrow Transplantation, (1999) 24, 561–566 1999 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0268–3369/99 $15.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/bmt Safety and efficacy of a continuous infusion, patient controlled anti- emetic pump to facilitate outpatient administration of high-dose chemotherapy SP Dix, MK Cord, SJ Howard, JL Coon, RJ Belt and RB Geller Blood and Marrow Transplant Program, Oncology and Hematology Associates and Saint Luke’s Hospital of Kansas City, Kansas City, MO, USA Summary: and colleagues1 described an outpatient BMT care model utilizing intensive clinic support following inpatient admin- We evaluated the combination of diphenhydramine, lor- istration of HDC. This approach facilitated early patient azepam, and dexamethasone delivered as a continuous discharge and significantly decreased the total number of i.v. infusion via an ambulatory infusion pump with days of hospitalization associated with BMT. More patient-activated intermittent dosing (BAD pump) for recently, equipped BMT centers have extended the out- prevention of acute and delayed nausea/vomiting in patient care approach to include administration of HDC in patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy (HDC) for the clinic setting. Success of the total outpatient care peripheral blood progenitor cell (PBPC) mobilization approach is dependent upon the availability of experienced (MOB) or prior to autologous PBPC rescue. The BAD staff and necessary resources as well as implementation of pump was titrated to patient response and tolerance, supportive care strategies designed to minimize morbidity and continued until the patient could tolerate oral anti- in the outpatient setting. emetics. Forty-four patients utilized the BAD pump Despite improvements in supportive care strategies, during 66 chemotherapy courses, 34 (52%) for MOB chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting continues to be and 32 (48%) for HDC with autologous PBPC rescue. -

Acute Migraine Treatment

Acute Migraine Treatment Morris Levin, MD Professor of Neurology Director, Headache Center UCSF Department of Neurology San Francisco, CA Mo Levin Disclosures Consulting Royalties Allergan Oxford University Press Supernus Anadem Press Amgen Castle Connolly Med. Publishing Lilly Wiley Blackwell Mo Levin Disclosures Off label uses of medication DHE Antiemetics Zolmitriptan Learning Objectives At the end of the program attendees will be able to 1. List all important options in the acute treatment of migraine 2. Discuss the evidence and guidelines supporting the major migraine acute treatment options 3. Describe potential adverse effects and medication- medication interactions in acute migraine pharmacological treatment Case 27 y/o woman has suffered ever since she can remember from “sick headaches” . Pain is frontal, increases over time and is generally accompanied by nausea and vomiting. She feels depressed. The headache lasts the rest of the day but after sleeping through the night she awakens asymptomatic 1. Diagnosis 2. Severe Headache relief Diagnosis: What do we need to beware of? • Misdiagnosis of primary headache • Secondary causes of headache Red Flags in HA New (recent onset or change in pattern) Effort or Positional Later onset than usual (middle age or later) Meningismus, Febrile AIDS, Cancer or other known Systemic illness - Neurological or psych symptoms or signs Basic principles of Acute Therapy of Headaches • Diagnose properly, including comorbid conditions • Stratify therapy rather than treat in steps • Treat early -

Hydroxyzine Prescribing Information

Hydroxyzine Hydroxyzine Hydrochloride Hydrochloride Injection, USP Injection, USP (For Intramuscular Use Only) (For Intramuscular Use Only) Rx Only Rx Only DESCRIPTION: Hydroxyzine hydrochloride has the chemical name of (±)-2-[2-[4-( p-Chloro- a- phenylbenzyl)-1-piperazinyl]ethoxy]ethanol dihydrochloride and occurs as a white, odorless powder which is very soluble in water. It has the following structural formula: Molecular Formula: C 21 H27 ClN 2O2•2HCl Molecular Weight: 447.83 Hydroxyzine Hydrochloride Injection, USP is a sterile aqueous solution intended for intramuscular administration. Each mL contains: Hydroxyzine HCl 25 mg or 50 mg, Benzyl Alcohol 0.9%, and Water for Injection q.s. pH adjusted with Sodium Hydroxide and/or Hydrochloric Acid. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY: Hydroxyzine hydrochloride is unrelated chemically to phenothiazine, reserpine, and meprobamate. Hydroxyzine has demonstrated its clinical effectiveness in the chemotherapeutic aspect of the total management of neuroses and emotional disturbances manifested by anxiety, tension, agitation, apprehension or confusion. Hydroxyzine has been shown clinically to be a rapid-acting true ataraxic with a wide margin of safety. It induces a calming effect in anxious, tense, psychoneurotic adults and also in anxious, hyperkinetic children without impairing mental alertness. It is not a cortical depressant, but its action may be due to a suppression of activity in certain key regions of the subcortical area of the central nervous system. Primary skeletal muscle relaxation has been demonstrated experimentally. Hydroxyzine has been shown experimentally to have antispasmodic properties, apparently mediated through interference with the mechanism that responds to spasmogenic agents such as serotonin, acetylcholine, and histamine. Antihistaminic effects have been demonstrated experimentally and confirmed clinically. -

5-HT3 Receptor Antagonists in Neurologic and Neuropsychiatric Disorders: the Iceberg Still Lies Beneath the Surface

1521-0081/71/3/383–412$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.118.015487 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 71:383–412, July 2019 Copyright © 2019 by The Author(s) This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC Attribution 4.0 International license. ASSOCIATE EDITOR: JEFFREY M. WITKIN 5-HT3 Receptor Antagonists in Neurologic and Neuropsychiatric Disorders: The Iceberg Still Lies beneath the Surface Gohar Fakhfouri,1 Reza Rahimian,1 Jonas Dyhrfjeld-Johnsen, Mohammad Reza Zirak, and Jean-Martin Beaulieu Department of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, Faculty of Medicine, CERVO Brain Research Centre, Laval University, Quebec, Quebec, Canada (G.F., R.R.); Sensorion SA, Montpellier, France (J.D.-J.); Department of Pharmacodynamics and Toxicology, School of Pharmacy, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran (M.R.Z.); and Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (J.-M.B.) Abstract. ....................................................................................384 I. Introduction. ..............................................................................384 II. 5-HT3 Receptor Structure, Distribution, and Ligands.........................................384 A. 5-HT3 Receptor Agonists .................................................................385 B. 5-HT3 Receptor Antagonists. ............................................................385 Downloaded from 1. 5-HT3 Receptor Competitive Antagonists..............................................385 2. 5-HT3 Receptor -

Effect of Naltrexone and Ondansetron on Alcohol Cue–Induced Activation of the Ventral Striatum in Alcohol-Dependent People

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Effect of Naltrexone and Ondansetron on Alcohol Cue–Induced Activation of the Ventral Striatum in Alcohol-Dependent People Hugh Myrick, MD; Raymond F. Anton, MD; Xingbao Li, MD; Scott Henderson, BA; Patrick K. Randall, PhD; Konstantin Voronin, MD, PhD Context: Medication for the treatment of alcoholism is double-blind randomly assigned daily dosing with 50 mg currently not particularly robust. Neuroimaging tech- of naltrexone (n=23), 0.50 mg of ondansetron hydro- niques might predict which medications could be use- chloride (n=23), the combination of the 2 medications ful in the treatment of alcohol dependence. (n=20), or matching placebos (n=24). Objective: To explore the effect of naltrexone, ondanse- Main Outcome Measures: Difference in brain blood tron hydrochloride, or the combination of these medi- oxygen level–dependent magnetic resonance when view- cations on cue-induced craving and ventral striatum ac- ing alcohol pictures vs neutral beverage pictures with a tivation. particular focus on ventral striatum activity comparison across medication groups. Self-ratings of alcohol craving. Design: Functional brain imaging was conducted dur- ing alcohol cue presentation. Results: The combination treatment decreased craving for alcohol. Naltrexone with (P=.02) or without (P=.049) Setting: Participants were recruited from the general ondansetron decreased alcohol cue–induced activation community following media advertisement. Experimen- of the ventral striatum. Ondansetron by itself was simi- tal procedures were performed in the magnetic reso- lar to naltrexone and the combination in the overall analy- nance imaging suite of a major training hospital and medi- sis but intermediate in a region-specific analysis. cal research institute. -

Hallucinogens: an Update

National Institute on Drug Abuse RESEARCH MONOGRAPH SERIES Hallucinogens: An Update 146 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services • Public Health Service • National Institutes of Health Hallucinogens: An Update Editors: Geraline C. Lin, Ph.D. National Institute on Drug Abuse Richard A. Glennon, Ph.D. Virginia Commonwealth University NIDA Research Monograph 146 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This monograph is based on the papers from a technical review on “Hallucinogens: An Update” held on July 13-14, 1992. The review meeting was sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. COPYRIGHT STATUS The National Institute on Drug Abuse has obtained permission from the copyright holders to reproduce certain previously published material as noted in the text. Further reproduction of this copyrighted material is permitted only as part of a reprinting of the entire publication or chapter. For any other use, the copyright holder’s permission is required. All other material in this volume except quoted passages from copyrighted sources is in the public domain and may be used or reproduced without permission from the Institute or the authors. Citation of the source is appreciated. Opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or official policy of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or any other part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The U.S. Government does not endorse or favor any specific commercial product or company. -

Important Interaction Between Mirtazapine and Ondansetron

SCIENTIFIC LETTER | http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ajpsy.v15i3.19 Afr J Psychiatry 2012;15:160 Important interaction between mirtazapine and ondansetron Drug interaction in psychiatry is a clinically important issue, as serotonergic antidepressant with a half-life of 20-40 hours. Apart it can cause side-effects and prevent adequate therapeutic from its presynaptic antagonistic effect on alpha 2-receptors with effect. We report an unexpected interaction between the release of both noradrenaline and serotonin – the postulated antidepressant mirtazapine and the antiemetic ondansetron in antidepressant effect – the compound antagonizes 5-HT2c, 5- a 72 year old patient, weighing 68 kg, with a height of 173 cm. HT2a (sedation, sleep, appetite) and 5-HT3-receptors (nausea). 1 The patient, who gave his informed consent for anonymous Ondansetron is a relatively specific 5-HT3-antagonist used publication, underwent electro-convulsive therapy (ECT), using particularly in postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in a Thymatron System II, Somatics LLC with bitemporal electrode intravenous 4 mg doses. 2 Ki-value (binding affinity of an inhibitor, position, energy 40 repeated with 50 % (corresponding ligand concentration which occupies 50% of a receptor) of charge: 257 mC, current: 0.92 A, duration of stimulation 7 sec, ondansetron is 7.6 nMol, i. e. approximately 1/9 of the Ki-value of frequency 40 Hz) due to chronic severe depression. He was on mirtazapine (about 70 nMol). 3 The affinity of mirtazapine – with pharmacological treatment with mirtazapine (45 mg daily) and regard to normal antidepressant dose up to 45 mg - was venlafaxine (75 mg daily). The patient complained of severe obviously not sufficient to block acute PONV, however, was able nausea and vomiting after the first ECT session. -

Guidelines for the Management of Nausea and Vomiting in Palliative Care

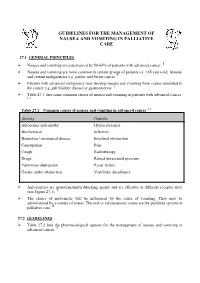

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF NAUSEA AND VOMITING IN PALLIATIVE CARE 27.1 GENERAL PRINCIPLES Nausea and vomiting are experienced by 50-60% of patients with advanced cancer. 1 Nausea and vomiting are more common in certain groups of patients i.e. <65 years old, females and certain malignancies e.g. gastric and breast cancer. 1 Patients with advanced malignancy may develop nausea and vomiting from causes unrelated to the cancer e.g. gall bladder disease or gastroenteritis. 1 Table 27.1 lists some common causes of nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced cancer. 1, 2 1, 2 Table 27.1 Common causes of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer Anxiety Gastritis Autonomic neuropathy Hypercalcaemia Biochemical Infection Brainstem / meningeal disease Intestinal obstruction Constipation Pain Cough Radiotherapy Drugs Raised intracranial pressure Functional obstruction Renal failure Gastric outlet obstruction Vestibular disturbance Anti-emetics are neurotransmitter-blocking agents and are effective at different receptor sites (see Figure 27.1). 3 The choice of anti-emetic will be influenced by the cause of vomiting. They may be administered by a variety of routes. The oral or subcutaneous routes are the preferred options in palliative care. 4 27.2 GUIDELINES Table 27.2 lists the pharmacological options for the management of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. 3 Table 27.2 Pharmacological options for the management of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 [Level 4] Drug name Type of drug Indication for Oral dose Parenteral dose Parenteral dose Notes use (subcutaneously over (subcutaneous stat 24 hours via a syringe doses) driver) Cyclizine Antihistamine Central causes. -

Management of Nausea in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease

Management of Nausea in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease Assessment • Assess duration and frequency of nausea and if any associated vomiting/abdominal pain/ constipation. • Assess and optimize possible contributing factors. • Glycemic control • Fluid status • Minimize/substitute medications that can cause nausea (e.g. opioids, tramadol, iron supplements, SSRI’s, bupropion, phosphate binders) • Inadequate dialysis prescription / underdialysis (if applicable) • Treat constipation if present Non-pharmacological Strategies • Liberalize diet restrictions (salt, phosphorus, potassium) if safe to do so. • Reduce or eliminate potentially nauseating stimuli (e.g., spicy, strong-smelling and high fat foods). Encourage a trial of cold, bland foods instead. • Try using ginger products (e.g. tea, tablet, ginger ale, cookies, candied ginger). • Eat frequent small, high calorie meals and snacks – hunger can make feelings of nausea stronger. • Sit upright or recline with head elevated for 30-60 min after meals. • Good oral hygiene – can help reduce unpleasant mouth taste contributing to nausea. • Wear loose clothing. • Apply a cool damp cloth on neck or forehead if very nauseous. • Consider relaxation, imagery, acupressure, acupuncture. • For PD patients, consider modifying PD exchange times and volumes around meals to minimize nausea that may be associated with eating. • See BCPRA patient teaching tool “Tips for People with Nausea and/or Poor Appetite.” Pharmacologic Interventions • Haloperidol, 0.25 to 0.75 mg po at HS increasing to BID then TID PRN OR • Methotrimeprazine, 2 to 5 mg po TID PRN (more sedating option) • If options above fail, consider a 5HT3 antagonist (e.g. Ondansetron, 4 to 8 mg po daily to BID PRN). • Note: Ondansetron is very expensive; consider risk of QT prolongation in the setting of possible electrolyte abnormalities. -

ZOFRAN® (Ondansetron Hydrochloride) Injection

PRESCRIBING INFORMATION ZOFRAN® (ondansetron hydrochloride) Injection DESCRIPTION The active ingredient in ZOFRAN Injection is ondansetron hydrochloride (HCl), the racemic form of ondansetron and a selective blocking agent of the serotonin 5-HT3 receptor type. Chemically it is (±) 1, 2, 3, 9-tetrahydro-9-methyl-3-[(2-methyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)methyl]-4H carbazol-4-one, monohydrochloride, dihydrate. It has the following structural formula: The empirical formula is C18H19N3O•HCl•2H2O, representing a molecular weight of 365.9. Ondansetron HCl is a white to off-white powder that is soluble in water and normal saline. Sterile Injection for Intravenous (I.V.) or Intramuscular (I.M.) Administration: Each 1 mL of aqueous solution in the 2-mL single-dose vial contains 2 mg of ondansetron as the hydrochloride dihydrate; 9.0 mg of sodium chloride, USP; and 0.5 mg of citric acid monohydrate, USP and 0.25 mg of sodium citrate dihydrate, USP as buffers in Water for Injection, USP. Each 1 mL of aqueous solution in the 20-mL multidose vial contains 2 mg of ondansetron as the hydrochloride dihydrate; 8.3 mg of sodium chloride, USP; 0.5 mg of citric acid monohydrate, USP and 0.25 mg of sodium citrate dihydrate, USP as buffers; and 1.2 mg of methylparaben, NF and 0.15 mg of propylparaben, NF as preservatives in Water for Injection, USP. ZOFRAN Injection is a clear, colorless, nonpyrogenic, sterile solution. The pH of the injection solution is 3.3 to 4.0. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Pharmacodynamics: Ondansetron is a selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. -

Ondansetron and the Risk of Cardiac Arrhythmias: a Systematic Review and Postmarketing Analysis

TOXICOLOGY/ORIGINAL RESEARCH Ondansetron and the Risk of Cardiac Arrhythmias: A Systematic Review and Postmarketing Analysis Stephen B. Freedman, MDCM, MSc; Elizabeth Uleryk, BA, MLS; Maggie Rumantir, MD; Yaron Finkelstein, MD* *Corresponding Author. E-mail: yaron.fi[email protected]. Study objective: To explore the risk of cardiac arrhythmias associated with ondansetron administration in the context of recent recommendations for identification of high-risk individuals. Methods: We conducted a postmarketing analysis and systematically reviewed the published literature, grey literature, manufacturer’s database, Food and Drug Administration Adverse Events Reporting System, and the World Health Organization Individual Safety Case Reports Database (VigiBase). Eligible cases described a documented (or perceived) arrhythmia within 24 hours of ondansetron administration. The primary outcome was arrhythmia occurrence temporally associated with the administration of a single, oral ondansetron dose. Secondary objectives included identifying all cases associating ondansetron administration (any dose, frequency, or route) to an arrhythmia. Results: Primary: No reports describing an arrhythmia associated with single oral ondansetron dose administration were identified. Secondary: Sixty unique reports were identified. Route of administration was predominantly intravenous (80%). A significant medical history (67%) or concomitant use of a QT-prolonging medication (67%) was identified in 83% of reports. Approximately one third occurred in patients receiving chemotherapeutic agents, many of which are known to prolong the QT interval. An additional third involved administration to prevent postoperative vomiting. Conclusion: Current evidence does not support routine ECG and electrolyte screening before single oral ondansetron dose administration to individuals without known risk factors. Screening should be targeted to high-risk patients and those receiving ondansetron intravenously.