Hero Worship, Frontline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films

South Asian Popular Culture ISSN: 1474-6689 (Print) 1474-6697 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsap20 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard To cite this article: Dickens Leonard (2015) Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films, South Asian Popular Culture, 13:2, 155-173, DOI: 10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Published online: 23 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsap20 Download by: [University of Hyderabad] Date: 25 October 2015, At: 01:16 South Asian Popular Culture, 2015 Vol. 13, No. 2, 155–173, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard* Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India This paper analyses contemporary, popular Tamil films set in Madurai with respect to space and caste. These films actualize region as a cinematic imaginary through its authenticity markers – caste/ist practices explicitly, which earlier films constructed as a ‘trope’. The paper uses the concept of Heterotopias to analyse the recurrence of spectacle spaces in the construction of Madurai, and the production of caste in contemporary films. In this pursuit, it interrogates the implications of such spatial discourses. Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films To foreground the study of caste in Tamil films and to link it with the rise of ‘caste- gestapo’ networks that execute honour killings and murders as a reaction to ‘inter-caste love dramas’ in Tamil Nadu,1 let me narrate a political incident that occurred in Tamil Nadu – that of the formation of a socio-political movement against Dalit assertion in December 2012. -

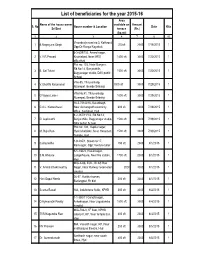

List of Beneficiaries for the Year 2015-16 Area Name of the House Owner Available on Amount S

List of beneficiaries for the year 2015-16 Area Name of the house owner available on Amount S. No House number & Location Date Kits Sri/Smt terrace (Rs.) (Sq.mt) 1 2 3 4 7 8 10 Viswabeeja road no:3, Kothapet, 1 B.Nagarjuna Singh 200sft 3000 7/15/2015 1 Opp:Dr.Ranga Nayakulu 6-3-609/153, Anand nagar, 2 V.V.R.Prasad Khairtabad, Near MRO 1400 sft 3000 7/20/2015 1 officeHyd Flat no: 103, Hotel Banjara, Rd.No:14, Banjarahills, 3 B. Sai Tulasi 1500 sft 3000 7/20/2015 1 Bagyanagar studio, DAV public School Villa-55, Thirusankalp, 4 V.Shanthi Karunamai 1000 sft 3000 7/29/2015 1 Nizampet, Beside Sribalaji Villa No:41, Thirusankalp, 5 G.Vijaya Laxmi 1000 sft 3000 7/29/2015 1 Nizampet, Beside Sribalaji 16-2-751/A/16, Karanbagh, 6 C.A.L. Kameshwari Near Asmangadh electricity 600 sft 3000 7/29/2015 1 office, Saidabad, Hyd 8-2-287/11/1/2, Rd.No:14, 7 D. Leelavathi Banjarahills, Bagyanagar studio, 1500 sft 3000 7/29/2015 1 DAV public School Plot no: 104, Kapila nagar, 8 M. Raja Rao Hydershahkote, Near Hanuman 1500 sft 3000 7/30/2015 1 Temple, Hyd 1-9-235/1, Street no:17, 9 C.Anuradha 150 sft 2000 8/1/2015 1 Ramnagar, Opp: Venture tailor 9-1-1/66/2, Hasimnagar, 10 S.M.Ghouse Langerhouse, Near fire station, 1700 sft 2000 8/1/2015 1 Hyd MIG-A-66, ECIL, Dr.AS Rao 11 V. -

S.No Marriage ID Status Village Mobile No Bride Name/Age Bride

Report on KALYANA LAKSHMI & SHAADI MUBHARAK SCHEME KAMAREDDY MANDAL S.No Marriage ID Status Village Mobile No Bride Name/Age Bride Groom Name/Age Address H.NO:2-88/1, GUDEM(V),H.NO:2-88/1, GUDEM(V),KAMAREDDY,KAMAREDDY,GUD 1 2019KL18522147 Amount Sanctioned for this Application GUDEM 9912383189 BOYA RAVALI-22 AYYAVARI SRIKANTH-24 EM,503111 HNO 1-2/1 RAMESWARPALLY (MDL)KAMAREDDY(DIST)KAMAREDDY TELANGANA 503111,HNO 1-2/1 RAMESWARPALLY (MDL)KAMAREDDY(DIST)KAMAREDDY TELANGANA 503111,KAMAREDDY,KAMAREDDY,RAMES 2 2019KL18540015 Amount Sanctioned for this Application RAMESWARPALLE 8712506790 KOORAKULA MOUNIKA-20 Kaveti Devaraju-28 WARPALLE,503111 H.NO: 1-4-592/15/3, SAILANI BABA COLONY, KAMAREDDY.,H.NO: 1-4-592/15/3, SAILANI BABA COLONY, KAMAREDDY.,KAMAREDDY,KAMAREDDY,KA 3 2019SM18164198 Amount Sanctioned for this Application KAMAREDDY ( U ) 9700527455 MOHAMMADI-27 MOHAMMED SHOYABUDDIN-34 MAREDDY ( U ),503111 1-4-516/B, PANCHAMUKHI HANUMAN COLONY,1-4-516/B, PANCHAMUKHI HANUMAN COLONY,KAMAREDDY,KAMAREDDY,KAMAR 4 2019SM18150990 Amount Sanctioned for this Application KAMAREDDY ( U ) 9346410689 SANIYA AFREEN-24 ZAKI UL HASNAIN-34 EDDY ( U ),503111 1-12-49/2, BATHUKAMMA KUNTA, KAMAREDDY DIST- 503111,1-12-49/2, BATHUKAMMA KUNTA, KAMAREDDY DIST- 503111,KAMAREDDY,KAMAREDDY,KAMARE 5 2019KL18512291 Amount Sanctioned for this Application KAMAREDDY ( U ) 9948842219 DANDLA ALIVENI-27 VAVILALA NAGARAJU-28 DDY ( U ),503111 4-119,4- 119,KAMAREDDY,KAMAREDDY,ADLOOR,50 6 2020KL18637979 Amount Sanctioned for this Application ADLOOR 9553772525 Kalluri Radha-28 MALLAMARI -

Annexure 1B 18416

Annexure 1 B List of taxpayers allotted to State having turnover of more than or equal to 1.5 Crore Sl.No Taxpayers Name GSTIN 1 BROTHERS OF ST.GABRIEL EDUCATION SOCIETY 36AAAAB0175C1ZE 2 BALAJI BEEDI PRODUCERS PRODUCTIVE INDUSTRIAL COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED 36AAAAB7475M1ZC 3 CENTRAL POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE 36AAAAC0268P1ZK 4 CO OPERATIVE ELECTRIC SUPPLY SOCIETY LTD 36AAAAC0346G1Z8 5 CENTRE FOR MATERIALS FOR ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY 36AAAAC0801E1ZK 6 CYBER SPAZIO OWNERS WELFARE ASSOCIATION 36AAAAC5706G1Z2 7 DHANALAXMI DHANYA VITHANA RAITHU PARASPARA SAHAKARA PARIMITHA SANGHAM 36AAAAD2220N1ZZ 8 DSRB ASSOCIATES 36AAAAD7272Q1Z7 9 D S R EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY 36AAAAD7497D1ZN 10 DIRECTOR SAINIK WELFARE 36AAAAD9115E1Z2 11 GIRIJAN PRIMARY COOPE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED ADILABAD 36AAAAG4299E1ZO 12 GIRIJAN PRIMARY CO OP MARKETING SOCIETY LTD UTNOOR 36AAAAG4426D1Z5 13 GIRIJANA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED VENKATAPURAM 36AAAAG5461E1ZY 14 GANGA HITECH CITY 2 SOCIETY 36AAAAG6290R1Z2 15 GSK - VISHWA (JV) 36AAAAG8669E1ZI 16 HASSAN CO OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UNION LTD 36AAAAH0229B1ZF 17 HCC SEW MEIL JOINT VENTURE 36AAAAH3286Q1Z5 18 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISER COOPERATIVE LIMITED 36AAAAI0050M1ZW 19 INDU FORTUNE FIELDS GARDENIA APARTMENT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 36AAAAI4338L1ZJ 20 INDUR INTIDEEPAM MUTUAL AIDED CO-OP THRIFT/CREDIT SOC FEDERATION LIMITED 36AAAAI5080P1ZA 21 INSURANCE INFORMATION BUREAU OF INDIA 36AAAAI6771M1Z8 22 INSTITUTE OF DEFENCE SCIENTISTS AND TECHNOLOGISTS 36AAAAI7233A1Z6 23 KARNATAKA CO-OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCER\S FEDERATION -

VOLVIV January 2015 No. 1 HIGHLIGHTS

VOLVIV January 2015 No. 1 HIGHLIGHTS Censor Board revamped Padma Awards announced 13th Pune International Film Festival held 60th Britannia Filmfare Awards presented Karnataka State Film Awards announced PK tax free in UP and Bihar Birth centenary of Honnappa Bhagavathar celebrated NATIONAL DOCUMENTATION CENTRE ON MASS COMMUNICATION NEW MEDIA WING (FORMERLY RESEARCH, REFERENCE AND TRAINING DIVISION ) MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING Room No.437-442, Phase IV, Soochana Bhavan, CGO Complex, New Delhi-3 Compiled, Edited & Issued by National Documentation Centre on Mass Communication NEW MEDIA WING (Formerly Research, Reference & Training Division) Ministry of Information & Broadcasting Chief Editor L. R. Vishwanath Editor H.M.Sharma Asstt. Editor Alka Mathur CONTENTS FILM AWARDS Bafta 2 Filmfare 4-5 Padma 1-2 State 6-7 FESTIVALS Indian Panorama 2-3 Pune International 3-4 OBITUARIES 8-11 PUBLICATIONS 7 REVIEW/DEVELOPMENT 1 REVIEW/DEVELOPMENT IN STATES 11 TAXATION 7 REVIEW/DEVELOPMENT Censor Board revamped In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (1) of section 3 of the Cinematograph Act 1952 (37 of 1952) read with rule 3 of the Cinematograph (Certification) Rules, 1983, the Central government has appointed Shri Pahlaj Nihalani as Chairperson of the Central Board of Film Certification in an honorary capacity for a period of three years or until further orders, whichever is earlier. Further, In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (1) of section 3 of the Cinematograph (Certification) Rulers, 1983, the Central government has appointed the following persons as members of the Central Board of Film Certification with immediate effect for a period of three years and until further orders:- Shri Mihir Bhuta, Prof Syed Abdul Bari, Shri Ramesh Patange, Shri George Baker, Dr. -

TAMIL CINEMA Tamil Cinema

TAMIL CINEMA Tamil cinema (also known as Cinema of Tamil Nadu, the Tamil film industry or the Chennai film industry) is the film industry based in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India, dedicated to the production of films in the Tamil language. It is based in Chennai's Kodambakkam district, where several South Indian film production companies are headquartered. Tamil cinema is known for being India's second largest film industry in terms of films produced, revenue and worldwide distribution,[1] with audiences mainly including people from the four southern Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andra Pradesh, and Karnataka. Silent films were produced in Chennai since 1917 and the era of talkies dawned in 1931 with the film Kalidas.[2] By the end of the 1930s, the legislature of the State of Madras passed the Entertainment Tax Act of 1939.[3] Tamil cinema later had a profound effect on other filmmaking industries of India, establishing Chennai as a secondary hub for Telugu cinema, Malayalam cinema, Kannada cinema, and Hindi cinema. The industry also inspired filmmaking in Tamil diaspora populations in other countries, such as Sri Lankan Tamil cinema and Canadian Tamil cinema.[6] Film studios in Chennai are bound by legislation, such as the Cinematography Film Rules of 1948,[7] the Cinematography Act of 1952,[8] and the Copyright Act of 1957.[9] Influences Tamil cinema has been impacted by many factors, due to which it has become the second largest film industry of India. The main impacts of the early cinema were the cultural influences of the country. The Tamil language, ancient than the Sanskrit, was the medium in which many plays and stories were written since the ages as early as the Cholas. -

Directory of Officers/Employees of Nrsc and Structure of Emoluments As on 01.10.2018

DIRECTORY OF OFFICERS/EMPLOYEES OF NRSC AND STRUCTURE OF EMOLUMENTS AS ON 01.10.2018 Level of Pay in the S No Name Designation Telephone Numbers Pay Matrix 1 AAKASH MOHAN SCI./ENG.-SC 10 08542-225419 2 AARATHI RAMESH MUPPALLA SCI./ENG.-SD 11 08542-225587 3 ABDUL HAKEEM K SCI./ENG.-SG 13A 040-23884262 4 ABHIJIT MADHUSUDHAN PILLAI SCI./ENG.-SE 12 040-23884478 5 ABHINAV KUMAR SHUKLA SCI./ENG.-SD 11 040-23884250 6 ABHISHEK CHAKRABORTY SCI./ENG.-SF 13 040-23884318 7 ADIBA FIRDOUS NIZAMI SCI./ENG.-SE 12 040-23884436/31 8 AJOY MONDAL SCI./ENG.-SF 13 033-23410018 9 AKASH GOYAL SCI./ENG.-SD 11 - 10 ALOK TAORI SCI./ENG.-SF 13 040-23884608 11 AMANPREET SINGH SCI./ENG.-SD 11 040-23884547 12 AMIT CHANDRA MISHRA SCI./ENG.-SD 11 040-23884325 13 AMIT KUMAR SR. ASSISTANT 6 033-23410055 14 AMIT KUMAR SINGH SCI./ENG.-SD 11 040-23884431 15 AMRITA SINGH SCI./ENG.-SD 11 040-23884564 16 AMRUTHA THANKACHAN ASSISTANT 4 040-23884129 17 ANAND ARUR SCI./ENG.-SE 12 0712-6621206 18 ANAND FRANCIS TECHNICIAN-B 3 040-23884232 19 ANAND KUMAR M SCI./ENG.-SF 13 040-23884153 20 ANAND KUMAR SINGH B JUNIOR ENGINEER 11 08542-225109 21 ANAND RAO G TECHNICIAN-D 4 040-23884423 22 ANANTH RAO SCI./ENG.-SE 12 040-23884810 23 ANANTHA PADMANABHA ERRA SCI./ENG.-SF 13 040-23884474 24 ANIL KUMAR G SCI./ENG.-SF 13 040-23884491 25 ANIL YADAV SCI./ENG.-SD 11 040-23884106 26 ANILKUMAR A SR. -

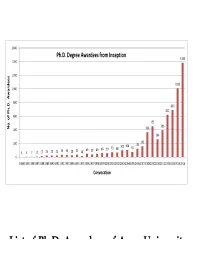

List of Ph.D. Awardees of Anna University List of Ph.D

1600 Ph.D. Degree Awardees from Inception 1385 1400 1200 1010 1000 800 690 622 600 455 396 No. of Ph.D. Awardees Awardees ofofPh.D. Ph.D. No.No. 400 366 264 200 162 101 106 124 73 68 76 36 33 35 49 39 49 60 59 3 5 7 12 17 25 25 25 28 18 0 198419851986198719881989199019911992199319941995199519961997199819992000200120022003200420052006200720082010201020122013201320142016 Convocation List of Ph.D. Awardees of Anna University List of Ph.D. Awardees of Anna University from the Inception 36th CONVOCATION HELD ON 20.01.2016 YEAR OF Sl.No Sl. NO NAME REGNO FACULTY AWARD Jan-16 1 1 Abdul Bari J 100960221002 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 2 2 Ambily P.S 1022119706 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 3 3 Arulkumaran S 10990221003 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 4 4 Arulmozhi R 10990221004 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 5 5 Arun Babu E 2713119707 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 6 6 Arun M 100930221003 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 7 7 Aruna S 2922119105 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 8 8 Aswin Sidhaarth K.R 100910211004 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 9 9 Balaji S 10960221005 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 10 10 Bhagavathi Pushpa T 20091032002 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 11 11 Divya Y 1024119111 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 12 12 Gopikrishnan T 1014119107 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 13 13 Gopikumar S 2011110104 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 14 14 Gopinathan Mj 4089023103 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 15 15 Hema S 7083022203 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 16 16 Jeevarenuka K 20091032005 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 17 17 Jerlin Regin J 2009710105 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 18 18 Kalai Selvan P 2006119701 CIVIL ENGINEERING Jan-16 19 19 Kalidasan -

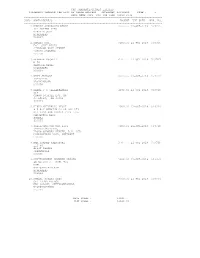

Unclaimed Dividend Page : 1 Bank Name :Sbi for the Year :2010-2011 ------Slno Name/Address Amount Due Date War

SMS PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT SHOWING THE LIST OF SHARE HOLDERS - UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND PAGE : 1 BANK NAME :SBI FOR THE YEAR :2010-2011 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SLNO NAME/ADDRESS AMOUNT DUE DATE WAR. NO. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1.KUNADI SUDARSHAN REDDY 3000.00 21-OCT-2018 509705 101 ANITHA APTS NARAYAN GUDA HYDERABAD 500007 2.RAMESH RAVI 3000.00 21-OCT-2018 509706 F-2 SIRI PLAZA SIVARAMA RAJU STREET LOYOLA GARDENS 520008 3.NEERAJA KOGANTI 6000.00 21-OCT-2018 509707 D-53 MADHURA NAGAR HYDERABAD 500038 4.RAVI JAYASRI 3000.00 21-OCT-2018 509709 40-9/1-15 VASYYANAGAR 520008 5.RADHA V S VALLABHANENI 1650.00 21-OCT-2018 509710 968 CRAWN POINTEE EST. DR ST.LOUIS, MD 63021 999999 6.HIREN NATVARLAL DESAI 3000.00 21-OCT-2018 509714 4 B ROY MANSION CO OP SOC LTD OPP ARAM SOC VAKOLA PIPE LINE SANTACRUZ EAST MUMBAI 400055 7.MALLIKHARJUNA RAO DIVI 3000.00 21-OCT-2018 509728 7-1-215/D/1/401, YASHO CHANDRA HEAVEN, B.K. GUD DHARAMKARAN ROAD, AMEERPET 500016 8.RAM PRASAD CHERUKURI 3000.00 21-OCT-2018 509738 LIG 80 APIIC COLONY JEEDIMETLA 500055 9.GHATTAMANENI HANUMAN PRASAD 1923.00 21-OCT-2018 509750 QR NO 899 G BHEL T/S BHEL RAMACHANDRAPURAM HYDERABAD 502032 10.KONERU SURESH BABU 3750.00 21-OCT-2018 509764 SFI ARUNA PALACE KRM COLONY, SEETHAMMADHARA VISAKHAPATNAM 530013 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- PAGE TOTAL : 31323.00 CUM TOTAL : 31323.00 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SMS PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT SHOWING THE LIST OF SHARE HOLDERS - UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND PAGE : 2 BANK NAME :SBI FOR THE YEAR :2010-2011 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SLNO NAME/ADDRESS AMOUNT DUE DATE WAR. -

Carvaan Mini Kannada Song List

01. Aadisinodu Beelisinodu 10. Thamnnam Thamnam 19. Ninna Nanna 28. Malenaada Henna 36. Prema Preeti Nannusiru 45. Preethine Aa Dyavaru Thanda 54. Kaalavannu Thadeyoru Yaaru 63. Ninna Kanna Notadalle Album: Kasturi Nivasa Album: Eradu Kanasu Album: Bhagyavantharu Album: Bhootayyana Maga Ayyu Album: Singapoorinalli Raja Kulla Album: Doorada Betta Album: Kittu Puttu Album: Babruvahana Artiste: P.B. Sreenivas Artistes: P.B. Sreenivas, S. Janaki Artiste: Dr. Rajkumar Artistes: P.B. Sreenivas, S. Janaki Artistes: S.P. Balasubrahmanyam, Artistes: P.B. Sreenivas, P. Susheela Artistes: K.J. Yesudas, S. Janaki Artiste: P.B. Sreenivas Lyricist: Chi Udayashankar Lyricist: Chi Udayashankar Lyricist: Chi Udayashankar Lyricist: Chi Udayashankar K.J. Yesudas Lyricist: Chi Udayashankar Lyricist: Chi Udayashankar Lyricist: Chi Udayashankar Music Director: G.K. Venkatesh Music Director: Rajan-Nagendra Music Director: Rajan-Nagendra Music Director: G.K. Venkatesh Lyricist: Chi Udayashankar Music Director: G.K. Venkatesh Music Director: Rajan-Nagendra Music Director: T.G. Lingappa Music Director: Rajan-Nagendra 02. Neerabittu Nelada Mele 11. Jeeva Veene 20. Beladingalaagi Baa 29. Cheluveya Andada 46. Thai Thai Bangari 55. Olave Jeevana - Duet (Sad) 64. Nee Nadeva Haadiyalli Album: Hombisilu Album: Hombisilu Album: Huliya Haalina Mevu Album: Devara Gudi 37. Ee Samaya Album: Giri Kanye Album: Sakshatkara Album: Bangarada Hoovu Artiste: S.P. Balasubrahmanyam Artistes: S.P. Balasubrahmanyam, S. Janaki Artiste: Dr. Rajkumar Artiste: S.P. Balasubrahmanyam Album: Babruvahana Artiste: Dr. Rajkumar Artistes: P.B. Sreenivas, P. Susheela Artistes: P. Susheela, S. Janaki Lyricist: Geethapriya Lyricist: Geethapriya Lyricist: Chi Udayashankar Lyricist: Chi Udayashankar Artistes: Dr. Rajkumar, S. Janaki Lyricist: Chi Udayashankar Lyricist: K. P. Sastry Lyricist: Vijaya Narasimha Music Director: Rajan-Nagendra Music Director: Rajan-Nagendra Music Director: G.K. -

Vishnuvardhan's Death Marks End of An

10 NRI PULSE ........ India Pulse ........ January 2010 Stir For Separate Thousands Gather For Telangana Meet At Osmania Vidarbha State Hyderabad: (IANS) Thousands of students There were loud cheers as the balladeers JAC leaders alleged that the police were Nagpur: (IANS) Several political groups and from various parts of Telangana gathered at the through their songs in the traditional Telangana violating court order by arresting students and social organisations participated in a two-day sit- Osmania University here to demand that the style underlined the need for Telangana state and using repressive measures to foil the meeting. In in agitation here to press the demand for a sepa- central government immediately initiate the highlighted the injustice meted out to the region Warangal, police stopped vehicles carrying rate Vidarbha state. process for granting statehood to the region. by successive rulers from Andhra. students of Kakatiya University to Hyderabad The initiative has been taken by Congress MP In what was seen as the biggest on the ground that the vehicles had no permission Vilas Muttemwar who led around 2000 people at the show of strength by Telangana to ply. peaceful sit-in (dharna) before a statue of Mahatma supporters since the movement The high court Saturday allowed the JAC to Gandhi at Variety Square in the heart of the city. The gathered steam a month ago, thousands hold the meeting but barred political leaders and agitators have demanded that along with the recently- of students from Hyderabad and nine Maoists from addressing it. approved proposal for a Telangana state, the central other districts of the region gathered at The all-party JAC comprises of members government should also “favorably” consider the 50- the sprawling university campus. -

Puttanna Kanagal Movies

RESEARCH PAPER Media Volume : 5 | Issue : 6 | June 2015 | ISSN - 2249-555X A critically Analysis: Puttanna Kanagal movies KEYWORDS Dr.Nagendra Assistant Professor, Sri Siddhartha Center for Media Studies, SSIT-Campuse, Maralure, Tumkur Intruduction: Film field has all about 115 years of history. As Indian Film Research objectives field is having about 80 years of history. Kannada film in- General and specific objectives of Studies in Puttanna dustry in India is having very significant history. Kanagal films is as below. In Kannada film industry Commercial and new trend mov- General Objectives. ies have been producing in quite large numbers. In Kan- 1. To describe briefly Kannada film industries origin and nada film history Puttanna Kanagal is being considered as development very talented and creative grate director in south Indian 2. To learn Puttanna kanagal’s multi talented distinctive language films director. In Kannada film industry he has character. created one new special drift. From Malayalam’s ‘SCHOOL MASTER’ movie to ‘MASANADA HOOVU’ movie he has Specific objectives directed about 36 movies and made kannada film indus- • Puttanna Kanagl’s given significance of Kannada films try very rich and become popular in kannada film industry. Industries Puttannakanagal movies have spread Kannada language • Puttanna puttann’s as Direction of basics elements, im- popularity worldwide. His movies has provided Kannada portance of publics for Social issues nationwide platform. • Puttanna Kanaglu’s theme of Story, acting, music’s, Photography and Direction for evaluating etc.. In 60th decades Puttannakanagal worked as assistant direc- • Evaluating Puttanna Kannagalu films Direction’s poli- tor under famous director B R Panthalu at the same dec- cies.