Malaspina College History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Points of Service

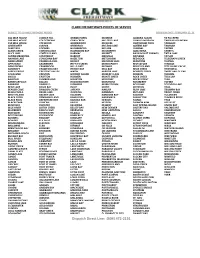

CLARK FREIGHTWAYS POINTS OF SERVICE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE REVISION DATE: FEBRUARY 12, 21 100 MILE HOUSE COBBLE HILL GRAND FORKS MCBRIDE QUADRA ISLAND TA TA CREEK 108 MILE HOUSE COLDSTREAM GRAY CREEK MCLEESE LAKE QUALICUM BEACH TABOUR MOUNTAIN 150 MILE HOUSE COLWOOD GREENWOOD MCGUIRE QUATHIASKI COVE TADANAC AINSWORTH COMOX GRINDROD MCLEOD LAKE QUEENS BAY TAGHUM ALERT BAY COOMBS HAGENSBORG MCLURE QUESNEL TAPPEN ALEXIS CREEK CORDOVA BAY HALFMOON BAY MCMURPHY QUILCHENA TARRY'S ALICE LAKE CORTES ISLAND HARMAC MERRITT RADIUM HOT SPRINGS TATLA LAKE ALPINE MEADOWS COURTENAY HARROP MERVILLE RAYLEIGH TAYLOR ANAHIM LAKE COWICHAN BAY HAZELTON METCHOSIN RED ROCK TELEGRAPH CREEK ANGELMONT CRAIGELLA CHIE HEDLEY MEZIADIN LAKE REDSTONE TELKWA APPLEDALE CRANBERRY HEFFLEY CREEK MIDDLEPOINT REVELSTOKE TERRACE ARMSTRONG CRANBROOK HELLS GATE MIDWAY RIDLEY ISLAND TETE JAUNE CACHE ASHCROFT CRAWFORD BAY HERIOT BAY MILL BAY RISKE CREEK THORNHILL ASPEN GROVE CRESCENT VALLEY HIXON MIRROR LAKE ROBERTS CREEK THREE VALLEY GAP ATHALMER CRESTON HORNBY ISLAND MOBERLY LAKE ROBSON THRUMS AVOLA CROFTON HOSMER MONTE CREEK ROCK CREEK TILLICUM BALFOUR CUMBERLAND HOUSTON MONTNEY ROCKY POINT TLELL BARNHARTVALE DALLAS HUDSONS HOPE MONTROSE ROSEBERRY TOFINO BARRIERE DARFIELD IVERMERE MORICETOWN ROSSLAND TOTOGGA LAKE BEAR LAKE DAVIS BAY ISKUT MOYIE ROYSTON TRAIL BEAVER COVE DAWSON CREEK JAFFARY NAKUSP RUBY LAKE TRIUMPH BAY BELLA COOLA DEASE LAKE JUSKATLA NANAIMO RUTLAND TROUT CREEK BIRCH ISLAND DECKER LAKE KALEDEN NANOOSE BAY SAANICH TULAMEEN BLACK CREEK DENMAN ISLAND -

Ceremony Program

ii Vancouver Island University CONVOCATION PROGRAM June 6 & 7 • 2 0 1 1 THE CANDIDATE DEGREE OATH THE CHANCELLOR ADDRESSES THE CANDIDATES: Will each of you accept the degree to which you are entitled, with its inherent rights and privileges and the responsibility and loyalty which it implies? EACH CANDIDATE REPLIES: I accept this degree, with its inherent rights and privileges and the responsibility and loyalty which it implies. 1 MESSAGE FRom THE CHANCELLOR Congratulations Graduates, You have achieved an important milestone in your life and I am proud of each one of you. I encourage you to step out into the world with the knowledge and skill you have acquired at VIU and make it a better place. You represent the very best of what we do at Vancouver Island University. Education is the foundation that brings about personal development and growth within people and is the key to healthy economies and community sustainability. VIU is an organization that is focused on the success of students and communities. It is this strong sense of purpose that will continue to guide our decision making and shape the direction of VIU for many decades. To the learners and the communities that continue to support the efforts of Vancouver Island University, thank you. You are the truest measure of our success. We exist to serve and support you, and look forward to continuing to do so well into the future. I would like to congratulate Dr. Ralph Nilson and Board Chair Mike Brown for their vision and leadership. Together with the dynamic team of professionals working at VIU, our university is undertaking remarkable work in research, program development, economic and social development, Aboriginal engagement and cultural enrichment. -

NDP Recall Defence Faces Probe Busy Lin Es Block Ambulance Calls

Free speech Time to celebrate The champions What do pepper sprayed protes- North Coast Distance Education A penalty shot and a couple of ters have to do with a Terrace School marks 10 years with an yellow cards prove decisive in aviation company?\NEWS A:I.3 open housekCOMMUNrrY B1 men's soccer finals\SPORTS B6 93¢ PLUS 7¢ GST WEDNESDAY SEPTEMBE.R 23, 1998 TANDA.RD VOL. 11 NO. 24 NDP recall defence faces probe A 'covert operation' including 'dirty tricks'? Or a textbook well-organized political campaign? By JEFF NAGEL "fake" "letters to the editors prepared for "It was a campaign just like any other ray confirmed. SKEENA MLA Helmut Giesbrecht~is distribution to local papers as part of a campaign," Murray said. "We tackled this McPhee's presence for two weeks was rejecting suggestions his supporters did "dirty tricks" campaign. just like we would an election. This is the reported in news stories by the Standard as anything wrong in defending him "It's a load of crap," Giesbrecht said only way we know how to do a political early as Dec. 23. Murray says had she been against a recall campaign last winter. Thursday. "It's the biggest crock of horse fight ~ an organized campaign." a secret, covert operative, an interview Elections B.C. on Friday appointed foren- manure I've heard in a long time." "But this time we didn't just out-organize would not have been granted. sic auditor Ron Parks to investigate recall "There was no covert operation. There them, they didn't have the support they Both workers were paid and their salaries campaigns here, in Prince George and were no dirty tricks. -

2020 07 21 Circulation Package

Circulation Package Bere Point – Area A July 2020 July 2, 2020 Dear Mayors and Regional District Chairs: My caucus colleagues and I are looking forward to connecting with you all again at this year’s Union of British Columbia Municipalities (UBCM) Convention, being held virtually from September 22-24. UBCM provides a wonderful opportunity to listen to one another, share ideas, and find new approaches to ensure our communities thrive. With local, provincial, federal, and First Nations governments working together, we can continue to build a better BC. If you would like to request a meeting with a Cabinet Minister or with me as part of the convention, please note that due to the abbreviated format this year, these meetings will likely be scheduled outside of the regular program dates. To make your request, please register online at https://ubcmreg.gov.bc.ca/ (live, as of today). Please note that this year’s invitation code is MeetingRequest2020 and it is case sensitive. If you have any questions, please contact [email protected] or phone 250-213-3856. I look forward to being part of your convention, meeting with many of you, and exploring ways that we can partner together to address common issues. Sincerely, John Horgan Premier ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Office of the Web Site: Mailing Address: Location: Premier www.gov.bc.ca PO Box 9041 Stn Prov Govt Parliament Buildings Victoria BC V8W 9E1 Victoria 1 July 2, 2020 Ref: 255149 Dear Mayors and Regional District Chairs: In this unprecedented time, I believe it is more important than ever that we continue to connect and work together. -

•1 • •192 • Two of Our Dedicated Cashiers, an Example of Rotarians

ABOV CE E I S V E R OTARY L E R F S • • 1 9 0 9 2 I 5 9 N L A • 1 T • 7E 5N R N I O N A T A . N .C III AIMO, B Two of our dedicated cashiers, an example of Rotarians in Club Service. CLUB SERVICE CLUB SERVICE A. Club Venue his report, “for the first two years there was difficulty in deciding on a suitable meeting The Nanaimo Rotary Club had place. Finally, in 1922 the Club settled on the difficulty arranging for an appropriate Windsor Hotel (today known as The meeting place. In a letter to charter Dorchester) until the opening of the Malaspina members, elected secretary Jim Galbraith Hotel in 1927.” had this to say, “The committee to make The Malaspina Hotel was built by the arrangements for the holding of our weekly Nanaimo Community Hotel Association, a luncheons has had considerable difficulty group of Nanaimo businessmen who securing a suitable meeting place, as none of the financed the construction. It was built on hotels has a suitable dining room. Mrs. Gordon the water front, adjacent to the C.P.R. wharf of the Lotus Hotel (then on Bastion Street) has with an eye to attracting the travelling agreed to arrange a private room for us. Our public. Frank Cunliffe was President of the regular luncheon will commence at the Lotus on Association for twenty years. He was also Friday at 12:15 p.m. and tickets will be 75¢. President of the Nanaimo Rotary Club in Smokers to provide their own cigars.” The 1926-1927, the year the hotel opened on Lotus was nicknamed the Temperance July 30, 1927 according to the Free Press. -

Nalt Newsletter Nov 11

News from Newsletter of the Nanaimo & Area Land Trust Society November 2011 INSIDE: PROJECT NALT 3 Notice of A.G.M. 3 Return it for the River 4 Cheques and Shares 4 Water Quality Testing 5 JCP River Team 5 Thank You, Gillian 6 NALT’s Annual Picnic 6 Nursery News 7 I.C.C. Shares 8 Run for the Mountain 9 Thank You All 10 Autumn leaves in the Nanaimo River Photo: JCP River Team THE NANAIMO RIVER STEWARDSHIP (NRS) SYMPOSIUM: A GREAT BEGINNING! The NRS Symposium took place from September 23rd to 25th at Vancouver Island University (VIU); a first gathering of stakeholders working together to develop strategies for stewardship of the river. The symposium was an opportunity to put forth some key values of the river, identify current challenges, and begin to develop ideas for actions that work towards long-term sustainable stewardship of the river. Friday, September 23rd featured pre-symposium events throughout the day in and around the Nanaimo River. Participants from all walks of life enjoyed the day sea-kayaking, river-rafting, hiking up Mount Benson, canyon- zipping, or learning about the river through a guided walk along its banks. The abundance of spawning salmon was a highlight of many of the outings! Friday evening was truly full of ‘Meeting and Greeting’, as about 250 people mingled in the VIU theatre lobby and enjoyed refreshments. The evening program began with the premier of Paul Manly’s newest documentary video Voices of the River—a stunning visual presentation that recognized many of the different stakeholders, and outlined the current management of the river and its resources. -

In Our Own Words: Our Learners' Stories

5th Edition Art by Orca Wilson In Celebration of International Literacy Day, September 8, 2010 Our Learners’ Stories Volunteer Tutoring Program A partnership between Literacy Central Vancouver Island & Vancouver Island University Welcome to our fifth edition! We are celebrating International Literacy Day 2010, with this collection of learner writings. All of the writers are enrolled in the Volunteer Tutor Program, which is a joint project between Literacy Central Vancouver Island and Vancouver Island University (Nanaimo Campus). Some of our learners have seen their words published before and for others this is a new, exciting experience. We thank and congratulate all of our adult learners for their contributions. We also thank the tutors who encouraged their learners, helped them edit their work and assisted them in finding their voice. Literacy Tutor Coordinators Margaret Ames & Jacqueline Webster September 8, 2010 Special thanks to Wendy Chapplow for her assistance with the publication Table of Contents Page Learner Event 2010 – Celebrating Learning………….. 2 Crystal Carson Bullying………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Dianne Burn For My Father, Barry…………………………………………………… 4 Shawn Richards A Day with Dad……………………………………………………………… 5 Mary Thompson My Journey………………………………………………………………………… 6 Richard Stewart Recipe for Spring Rolls…………………………………………………… 7 Laiwan Lam Trip to Mexico…………………………………………………………………… 8 Lily Lee White Rapids……………………………………………………………………… 9 Larry Gallant Beating Boredom……………………………………………………………….. 10 Marcel Kemp Becoming a Dentist in Canada………………………………………. 11 Nahed Abel Alla Escape to a New Life……………………………………………………… 12 Grace Yang Nature and Nurture…………………………………………………………. 14 Marion Roper The Best Present Ever!..................................................... 15 Diane Gibbons My Mom……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 17 Evelyne Gomes My Story………………………………………………………………………………. 19 Shawn Richards Page 1 Learner Event 2010 - Celebrating Learning Crystal Carson We started at Literacy Central. -

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements The history of the Vancouver Island Real Estate Board (VIREB) reveals a dynamic account of professionalism, the unifying effort of many, and the motivation that drove the Board from its first day in 1951 through modernity. This narration endeavours to offer an objective viewpoint that unites documentation and individual recollection to tell the inspiring chronicle of the men and women who have joined forces in order to work towards a higher aim, a common vision. The history of VIREB reveals a philosophy of professionalism; its story is paralleled by the earned expertise of the real estate industry as a whole. It is with gratitude that the author recog- nizes those who were interviewed for the history as representatives of the evolving eras of the Board: Allan Armstrong, Pat Moore, Lloyd Wood, Reg Eaton, Ralph Walker, Bob Clarke, Gordon Blackhall, Jack Geisler, Dermot Murphy, Rick Evans (reflecting upon his Father Jack’s contribu- tion), Marty Douglas, Randy Forbes, and Donn Gardner. Their vast knowledge, strategic sense, and commitment to the industry are legendary and the history was not only told, but made with their help. While these Members and Associates have been instrumental in telling the story of the Board’s history they are not alone, countless Members stand equal in knowledge and commit- ment, and their actions are clearly recorded within the sixty years of Board Minutes. Above all, it is the Membership that directs the Board. It is that collective voice that has been the guiding force of VIREB; its history is the history of its Members. Supporting the Board Directors and Membership are the men and women that have orches- trated the business of the Board. -

A Critical Analysis of Apprenticeship Programs in British Columbia

A Critical Analysis of Apprenticeship Programs in British Columbia by Gregory Matte A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Policy Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020 Gregory Matte Abstract This study examines issues surrounding apprenticeships in the construction industry in British Columbia (BC) during the period of 1993 to 2004, particularly the state of the social settlement amongst its primary stakeholders, namely the government, unionized and non-unionized employment associations and post- secondary colleges. It provides a conceptual framework to research apprenticeships as a skills ecosystem, and to explain why successive provincial governments were motivated to impose significant legislative changes on the vocational education and training system. The findings not only examine the motivation, but also the resulting outcomes, using the different political ideologies as a basis to explain how contrasting stakeholder perspectives shaped both. Based on a combination of structure and agency, the primary stakeholders operated within the confines of institutional structures, extant logics and the limitations of their own perspectives and objectives. This thesis examines how the relationships between apprenticeships, the labour market and the post-secondary education system are coordinated, governed, influenced and shaped in BC, as well as how these same relationships have evolved, including the impact of such changes on apprenticeship programs as a skills ecosystem. The period of 1993 to 2004 was specifically chosen as it was a period of bold political reforms pertaining to trades training within the province by two ideologically opposed political parties. -

~~~®~!1 ~~~~~[JJ~®~ May 2, 19 79 Vo 1 3: No

~~~®~!1 ~~~~~[JJ~®~ May 2, 19 79 Vo 1 3: No. 29 JAPANESE GARDEN HANDED OVER THE COLLEGE'S NEW JAPANESE GARDEN WAS FORMALLY HANDED OVER on April 27 to Board chairman Beryl Bennett by Osamu Hashimoto. Tamagawa University's Director of International Education. Hashimoto, who had made a special journey from Tokyo to Nanaimo for the occasion, brought greetings from Tamagawa President Dr. Tetsuro Obara in which he emphasized the strength of the links between the two institutions. "It is our dearest wish. "he said, "that this garden shall become a living symbol of fellowship and goodwill between Tamagawa and Malaspina. It is our intention that the garden will serve as a place of recreation and relaxation for both College students and the people of Nanaimo. " The garden, located beside the Art Building, was constructed by a Vancouver based firm of landscape gardeners and includes a Japanese style tea house ' and a pool spanned by a bridge which Dr. Obara says stands for the "Bridge of Communication which has enabled :our unde r standing and friendsh i p to grow." It is our earnest hope," he added , "that this symbolic bridge will serve us well and that our future efforts wi ll be rewarded with an even greater depth of frie ndship and unders tanding. " The association between Malaspina and Tamagawa dates back to 1976 and Ta mag awa now owns farm acreage in the Cedar area south of Nanaimo. Plans for the future of the site have still to be announced but the expectation i s tha t it will be used for agric~ltura1 research projects. -

Administrative Opportunity - Superintendent of Schools

Administrative Opportunity - Superintendent of Schools School District No. 85 acknowledges with gratitude that it operates on traditional Kwakwaka’wakw territory. The Board of Education for School District No. 85 is seeking an innovative, transformational, resourceful, and collaborative educational leader to fulfill the role of Superintendent of Schools. The Board of Education will oversee an operating budget of approximately $18.5 million and, on behalf of the Board, a dedicated team of educators and support staff provide service to 1300 students in 10 schools in Port Hardy, Port McNeill, Port Alice, and Sointula. School District No. 85 honours the unique history and traditions of the communities of Port Hardy, Port McNeill, Fort Rupert, Coal Harbour, Port Alice, Sointula, Alert Bay, Woss Lake, Quatsino and Holberg. Aboriginal culture has flourished on Vancouver Island North for thousands of years and continues to be revered and respected today. The Central Administration Office for the School District is located in Port Hardy, the hub for education, health, transportation, and economic activity for the region, and the gateway for BC Ferries travel into north-western BC. The North Island region offers access to unspoiled wilderness, a wealth of outdoor sports and recreation activities, and all of the advantages of Island life. The Board is seeking a transformational educational leader to work with them to build on a long tradition of community-based service to learners, many of whom have Indigenous heritage. The Board and district staff have worked to create the focus, relationships, and commitments required to support the aspirations of parents, community members, and local First Nation leaders for their students. -

Regional Visitors Map Highlighting Parks, Trails and and Trails Parks, Highlighting Map Visitors Regional Large

www.sointulacottages.com www.northcoastcottages.ca www.umista.ca www.vancouverislandnorth.cawww.alertbay.ca www.porthardy.travel • www.ph-chamber.bc.ca • www.porthardy.travel P: 250-974-5403 P: 250-974-5024 P: P: 250-973-6486 P: Regional Features [email protected] 1-866-427-3901 TF: • 250-949-7622 P: 1 Front Street, Alert Bay, BC Bay, Alert Street, Front 1 BC Bay, Alert Street, Fir 116 Sointula, BC Sointula, Port Hardy, BC • P: 250-902-0484 P: • BC Hardy, Port 7250 Market St, Port Hardy, BC Hardy, Port St, Market 7250 40 Hiking Trail Mateoja Trail Adventure! the Park Boundary Culture Bere Point Regional Park & Campsite 8 The 6.4 km round-trip Mateoja Heritage Trail begins on Live and us visit Come hiking. & diving Cliffs To Hwy 19 There are 24 campsites nestled in the trees with the beach just 3rd Street above the town site. Points of interest include Boulderskayaking, fishing, beaches, splendid 1-888-956-3131 • www.portmcneill.net • 1-888-956-3131 A natural paradise! Abundant wildlife, wildlife, Abundant paradise! natural A [email protected] • winterharbourcottages.com • [email protected] the Mateoja farm site, an early 1900’s homestead, Little Cave with Horizontal Entrance Port McNeill, BC • P: 250-956-3131 P: • BC McNeill, Port a stone’s throw away, where250-969-4331 P: • youBC can enjoyHarbour, viewsWinter across Queen Cave with Vertical Entrance Charlotte Strait to the nearby snow-capped coast mountains. Lake, marshland at Melvin’s Bog, Duck Ponds and the local SOINTULA swimming hole at Big Lake. Decks and benches along the Parking This Park is within steps of the Beautiful Bay trailhead, and is a “Fern” route are ideal for picnics and birdwatchers.