Vacuum Appropriation Strategies Between Patio and Pavilion Archetypes Hybridization in Two Classical Masters Works of Modern Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

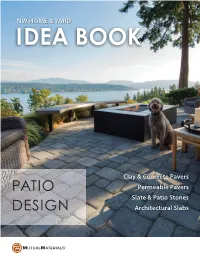

Patio Design Has Photos from Real Homes and Yards Across the Paci C Northwest

NW HOME & YARD IDEA BOOK Clay & Concrete Pavers PATIO Permeable Pavers Slate & Patio Stones DESIGN Architectural Slabs At Mutual Materials, we are proud of what we do and are inspired to see our products chosen by professionals to build communities. Our products build beauty that lasts through hospitals, schools, stadiums, businesses, family homes, public parks, and backyards. Mutual Materials has long served a professional network of architects, interior designers, builders, masons, and landscape design professionals. Today we also serve residential homeowners, both through our professional networks and through our retail branch locations. A Message from our President Have you ever spent time looking at your local sports stadium, or your child’s school, or even your neighbor’s backyard and wondered where the products come from that put it all together? Well, that’s what Mutual Materials does – we have been part of building beauty that lasts over one hundred years. Since 1900, we have been providing masonry and hardscape products to customers in the Paci c Northwest to help them create inviting communities that stand the test of time. Our products are used to create schools, stadiums, public landscapes, business parks, family homes and gardens, and much more. Mutual Materials is also a family business and we locally manufacture the products we Kendall Anderegg sell. From humble beginnings with one brick plant in 1900, we have grown today into a President, Mutual Materials major regional employer operating more than 10 manufacturing plants and 16 branch o ces across Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and British Columbia. Our Idea Book for Patio Design has photos from real homes and yards across the Paci c Northwest. -

Safety Barrier Guidelines for Residential Pools Preventing Child Drownings

Safety Barrier Guidelines for Residential Pools Preventing Child Drownings U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission This document is in the public domain. Therefore it may be reproduced, in part or in whole, without permission by an individual or organization. However, if it is reproduced, the Commission would appreciate attribution and knowing how it is used. For further information, write: U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission Office of Communications 4330 East West Highway Bethesda, Md. 20814 www.cpsc.gov CPSC is charged with protecting the public from unreasonable risks of injury or death associated with the use of the thousands of consumer products under the agency’s jurisdiction. Many communities have enacted safety regulations for barriers at resi- dential swimming pools—in ground and above ground. In addition to following these laws, parents who own pools can take their own precau- tions to reduce the chances of their youngsters accessing the family or neighbors’ pools or spas without supervision. This booklet provides tips for creating and maintaining effective barriers to pools and spas. Each year, thousands of American families suffer swimming pool trage- dies—drownings and near-drownings of young children. The majority of deaths and injuries in pools and spas involve young children ages 1 to 3 and occur in residential settings. These tragedies are preventable. This U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) booklet offers guidelines for pool barriers that can help prevent most submersion incidents involving young children. This handbook is designed for use by owners, purchasers, and builders of residential pools, spas, and hot tubs. The swimming pool barrier guidelines are not a CPSC standard, nor are they mandatory requirements. -

Backyard Design Essentials Tips to Turn Your Backyard Or Patio Into the Ideal Outdoor Space for Your Family

Backyard Design Essentials Tips to turn your backyard or patio into the ideal outdoor space for your family. Whether you have a smaller patio or an extensive backyard, there are several things you can do to turn it into a comfortable, outdoor oasis. In this guide, we take a look at backyard essentials, like fencing, shade structures, and furniture, that can turn a piece of land into a welcoming outdoor space for entertaining and relaxing. The Right Fence for Your Function There is a myriad of reasons to build a fence around your yard – privacy, setting the boundaries of your property, keeping your kids and dogs safe, and keeping critters and nosy neighbors out. Technology, taste and necessity have created a variety of fence types, in both look and material. There are options to match nearly every consideration and functionality. Before you choose your fence, consider your need for functionality, and preferences for security, privacy and maintenance. Security A good fence will keep the things you want in – and the things you don’t out. Of course, the level of security needed for each situation is unique. If you don’t want your small dog to escape, you won’t need a giant, steel-reinforced wall. A basic board fence should do the trick. Security is also about keeping things out of your yard – like critters. For example, if you live near a canyon, your yard is exposed to coyotes, rattle snakes and even the occasional curious mountain lion. Skunks, possums and rats roam many neighborhoods as well. If you live in an area where critters are abundant, you’ll want to build a fence that is snug to the ground and tall enough to deter intruders. -

The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance

•••••••• ••• •• • .. • ••••---• • • - • • ••••••• •• ••••••••• • •• ••• ••• •• • •••• .... ••• .. .. • .. •• • • .. ••••••••••••••• .. eo__,_.. _ ••,., .... • • •••••• ..... •••••• .. ••••• •-.• . PETER MlJRRAY . 0 • •-•• • • • •• • • • • • •• 0 ., • • • ...... ... • • , .,.._, • • , - _,._•- •• • •OH • • • u • o H ·o ,o ,.,,,. • . , ........,__ I- .,- --, - Bo&ton Public ~ BoeMft; MA 02111 The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance ... ... .. \ .- "' ~ - .· .., , #!ft . l . ,."- , .• ~ I' .; ... ..__ \ ... : ,. , ' l '~,, , . \ f I • ' L , , I ,, ~ ', • • L • '. • , I - I 11 •. -... \' I • ' j I • , • t l ' ·n I ' ' . • • \• \\i• _I >-. ' • - - . -, - •• ·- .J .. '- - ... ¥4 "- '"' I Pcrc1·'· , . The co11I 1~, bv, Glacou10 t l t.:• lla l'on.1 ,111d 1 ll01nc\ S t 1, XX \)O l)on1c111c. o Ponrnna. • The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance New Revised Edition Peter Murray 202 illustrations Schocken Books · New York • For M.D. H~ Teacher and Prie11d For the seamd edillo11 .I ltrwe f(!U,riucu cerurir, passtJgts-,wwbly thOS<' on St Ptter's awl 011 Pnlladfo~ clmrdses---mul I lr,rvl' takeu rhe t>pportrmil)' to itJcorporate m'1U)1 corrt·ctfons suggeSLed to nu.• byfriet1ds mu! re11iewers. T'he publishers lwvc allowed mr to ddd several nt•w illusrra,fons, and I slumld like 10 rltank .1\ Ir A,firlwd I Vlu,.e/trJOr h,'s /Jelp wft/J rhe~e. 711f 1,pporrrm,ty /t,,s 11/so bee,r ft1ke,; Jo rrv,se rhe Biblfogmpl,y. Fc>r t/Jis third edUfor, many r,l(lre s1m1II cluu~J!eS lwvi: been m"de a,,_d the Biblio,~raphy has (IJICt more hN!tl extet1si11ely revised dtul brought up to date berause there has l,een mt e,wrmc>uJ incretlJl' ;,, i111eres1 in lt.1lim, ,1rrhi1ea1JrP sittr<• 1963,. wlte-,r 11,is book was firs, publi$hed. It sh<>uld be 110/NI that I haw consistc11tl)' used t/1cj<>rm, 1./251JO and 1./25-30 to 111e,w,.firs1, 'at some poiHI betwt.·en 1-125 nnd 1430', .md, .stamd, 'begi,miug ilJ 1425 and rnding in 14.10'. -

RESIDENTIAL PATIO / PATIO COVER / DECK REGULATIONS and PLANS REQUIREMENTS Residential Patios Patio Covers PLAN REQUIREMENTS

RESIDENTIAL PATIO / PATIO COVER / DECK REGULATIONS AND PLANS REQUIREMENTS Residential Patios This permit applies only to concrete poured patios. A permit is required when the patio is proposed to be connected to the house and/or 30 inches or more above grade. PLAN REQUIREMENTS: Plans are required to be in sufficient detail and size to properly determine code compliance. Additional information may be required. A typical grouping of plans is: 1. Plot plan or survey. A plan that shows: a. The Property lines b. Any currently existing buildings, fences, houses, etc. c. Setbacks, easements, rights of way, etc. d. The location of the proposed construction. 2. Structural plan. A plan that shows: a. The structural component of the patio (i.e. rebar or wire mesh) b. Perimeter beams if applicable c. Attachment to the house. (Regardless of the requirement for a permit, patios must not be located in Public Utility Easements or Drainage Easements. Refer to the survey of your lot for the location of easements.) PERMIT FEE: Without Utilities: $48.00 Patio Covers Any patio cover requires a permit. SET BACK REQUIREMENTS: 25 Feet from the Front yard property line to the edge of the patio cover foundation. 5 Feet from the Interior side yard property line to the edge of the patio cover foundation. 15 Feet from the Exterior side yard property line on a corner lot to the edge of the patio cover foundation. Public Utility Easements (PUEs) may be larger than the above setbacks, in which case the PUE must be used as the setback. PLAN REQUIREMENTS Plans are required to be in sufficient detail and size to properly determine code compliance. -

Conservatories | Orangeries | Extensions

ebrati el ng C 45* years OF TRADING Conservatories | Orangeries | Extensions As Part of One Group Construction 2 www.sehbac.com SEH BAC LIFESTYLE Why choose us? Lifestyle Honest advice, expert SPACE • LIGHT • QUALITY installations, and a stunning range of windows, doors and conservatories You might not know it, but your home has potential – not just to be bigger or brighter perfectly tailored to or higher in value, but to give you a better standard of living. you and your home Maybe you feel you’ve outgrown your existing property, and are yearning for – that’s what you get something more spacious and stylish – something more ‘you’. Maybe moving feels when you work with like the only option. But it isn’t. SEH BAC, one of the region’s longest-serving home improvement With the right products, meticulous planning and expert execution, you’d be amazed companies. at how much a conservatory, an orangery or an extension project can transform your home – and how much it can save you compared to a house move. For 45 years, as part of One Group Construction, we’ve dedicated ourselves to Moving costs tens of thousands of pounds. On top of the price of the property itself, providing quality products and exceptional there’s stamp duty and estate agent fees to consider – and the average homeowner customer service, successfully completing then goes on to spend £10,000 renovating their new home in the first year of thousands of projects across the South East of owning it. England. In other words, you can spend a small fortune moving house, or for a fraction of the We’ve got the passion, the knowledge and the cost, you can transform your existing home. -

Patio Door Multi‐Point Lock Hardware Is Available

Hardware Options Patio Door Multi‐point lock hardware is available. Single point and multi‐point locks are available with key cylinder. Security SPECIFICATIONS bolt or security bar hardware is available for extra security. Screen Frame and Sash North Star heavy duty extruded aluminum screen frame All frame and sash profiles are extruded by North Star with adjustable steel rollers, screened with anti‐glare Windows from virgin PVC powder material. Frames and sash fiberglass cloth. Screen frame is available in white and North are multi‐chamber design for strength and energy efficiency. Star’s seven standard exterior colors. Extruded frame is mechanically fastened at corners and sealed with one‐sided adhesive backed closed cell Exterior and Interior Finishes polyethylene gaskets. The door frame’s low profile sill is North Star standard vinyl extrusion has a clean, bright, white fitted with an extruded anodized aluminum screen track. smooth finish. Seven North Star exterior textured color Extruded sash are fusion welded ensuring a water and finishes (ivory, chestnut brown, cocoa, hickory, sandalwood, airtight seal. Sash is metal reinforced providing superior sable and espresso) and two interior wood grains (Kolonial rigidity. Frames are a full 5 ⅝” in depth. Oak and Stainable/Paintable Pine) are optional. Exterior Insulated Glass color and interior wood grain are applied PVC laminate film with an acrylic overlay for exceptional UV protection. 3mm tempered double or triple insulating glass with Exterior laminate is 200µm (microns) thick. Special option: Edgetech silicone foam low conductive S‐Class Super espresso interior laminate combined with espresso exterior Spacer®. Pilkington Energy Advantage ™ Low E (hard coat) laminate is available for patio doors. -

Home Landscape Planning Worksheet: 12 Steps to a Functional Design

Home Landscape Planning Worksheet: 12 steps to a functional design This worksheet will guide you through the process of Gather information designing a functional landscape plan. The process includes these steps: Step 1. Make a scale drawing • Gather information about the site and who will use it. Landscape designs are generally drawn from a bird’s- • Prioritize needs and wants. eye view in what designers call “plan view.” To prepare a base map (scale drawing) of your property use graph • Consider maintenance requirements. paper and let one square equal a certain number of feet • Determine a budget. (e.g. 1 square = 2 feet), or draw it to scale using a ruler • Organize the landscape space. or scale (e.g. 1 inch = 8 feet). • Determine the shape of the spaces and how they The base map should include these features: relate to each other. • Scale used • Select the plants that will fi ll the landscape. • North directional arrow • Property lines Base Map and Initial Site Analysis (not to scale) You may want to make several photocopies of this base map to use for the following steps in the design process. Step 2. Site analysis A thorough site analysis tells you what you have to work NICE VIEW with on the property. Part 1 of the “Home Landscape Questionnaire” (see insert) includes questions that NEED PRIVACY should be answered when completing a site analysis. Lay a piece of tracing paper over the base map and draw the information gathered during the site analysis. This layer should include these features: KITCHEN/ DINING ROOM • Basic drainage patterns -

Renaissance Gardens of Italy

Renaissance Gardens of Italy By Daniel Rosenberg Trip undertaken 01-14 August 2018 1 Contents: Page: Introduction and overview 3 Itinerary 4-5 Villa Adriana 6-8 Villa D’Este 9-19 Vatican 20-24 Villa Aldobrindini 25-31 Palazzo Farnese 32-36 Villa Lante 37-42 Villa Medici 43-45 Villa della Petraia 46-48 Boboli Gardens 49-51 Botanical Gardens Florence 52 Isola Bella 53-57 Isola Madre 58-60 Botanic Alpine Garden Schynige Platte (Switz.) 61-62 Botanic Gardens Villa Taranto 63-65 Future Plans 66 Final Budget Breakdown 66 Acknowledgments 66 Bibliography 66 2 Introduction and Overview of project I am currently employed as a Botanical Horticulturalist at the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. I started my horticultural career later in life and following some volunteer work in historic gardens and completing my RHS level 2 Diploma, I was fortunate enough to secure a place on the Historic and Botanic Garden training scheme. I spent a year at Kensington Palace Gardens as part of the scheme. Following this I attended the Kew Specialist Certificate in Ornamental Horticulture which gave me the opportunity to deepen my plant knowledge and develop my interest in working in historic gardens. While on the course I was able to attend a series of lectures in garden history. My interest was drawn to the renaissance gardens of Italy, which have had a significant influence on European garden design and in particular on English Gardens. It seems significant that in order to understand many of the most important historic gardens in the UK one must understand the design principles and forms, and the classical references and structures of the Italian renaissance. -

Summit Stone Transforms Decade-Old Patio with Trending

CASE STUDY APPALOOSE COURT RESIDENCE Summit Stone Transforms Decade-Old Patio with Trending Hardscape Additions Ten years after first installing a patio, this Appleton, WI Summit Stone is available in seven sizes including a homeowner wanted to update and expand it into a full keystone shape capstone and can be easily split onsite outdoor living space. The patio’s decade-old pavers were to create special design features. The fireplace was still in such good condition, Maple Leaf Landscaping of constructed with the Summit Stone Standard Fireplace Appleton, WI and the homeowner decided to leave them Kit and features a custom built arch mantle designed by in place and incorporate Summit Stone Landscape Units Maple Leaf Landscaping. Hush colored block were used to create new hardscape elements. The homeowner for most of the fireplace, with the arch and several accent chose several trending hardscape features to transform layers made of Haven colored block. their pond-side patio, including a seat wall, fireplace, The kitchenette consists of the same size block kitchenette, and pillars. throughout, with a cast stone counter top and a built-in Maple Leaf Landscaping recommended Summit Stone grill. Summit Stone was used to create a backsplash with for the project because of the units’ modular design and a pillar on each side. One of the pillars supports a wooden easy installation. The homeowner chose Hush colored trellis over an entryway that leads from the driveway to blocks for their natural beige hue which complimented the patio. Another pillar supports a seat wall. The seat wall the existing pavers and Haven colored blocks for their borders the entire patio, creating an outdoor living room slightly darker earth tone, which created subtle accents and doubling as additional seating for large gatherings. -

Cloverwood Patio Home Footprint

tments ar ap o south green south o t oom r dining chen kit oom r dining oom r or direct dining vices ser e at priv dining ail lounge ail cockt manager age green age vill o t oom/ r club business café ant account r to coordina wm ces resour y suppl human mail computer ctr. computer housekeeping bar oom r thering ga y librar oom r tments ar ap conference th green th nor o t or direct y/reception lobb admin. executive . recp or direct ts ar tural cul studio office ts ar tive crea office billiards office barber shop barber salon/ cochere te por wood clover t a shoppe the oom r card center business fitness center fitness . vest o glenmere o t lockers mech. lockers men's pool women's Main Level Main indoor pool indoor CENTER VILLAGE Community Community SERVICES AMENITIES • Delicious, chef-prepared meals • Nicely appointed, bright and spacious • Recreational, social, cultural and educational • Apartment and patio homes programs • 41 acres of meadows and woodlands • Reception/concierge services • Multiple dining venues • Groundskeeping, snow removal and interior/ exterior maintenance • Indoor swimming/lap pool • Annual heavy cleaning and twice-monthly • State-of-the-art fitness center housekeeping • Library/computer resource center • 24-hour personal emergency response system • Billiard and game room and security services • Club room/cocktail lounge • All property taxes paid (town/county and school) • Meeting and gathering rooms • Wellness education and health promotion • Café and coffee shop programs PATIO HOME • Creative arts studio • Heat, -

EMERALD 1,341 Sq

ENCLAVE SERIES EMERALD 1,341 sq. ft. SPANISH PRAIRIE ITALIANATE 1.800.303.BRIO LIFEATBRIO.COM 230 W BRIO CLUBHOUSE DR WASHINGTON, UT 84780 ENCLAVE SERIES EMERALD OPTIONS 1,341 Total Sq. Ft., 3 Bedrooms, 2 Bathrooms, and 2-Car Garage. Master Bedroom Vault Master Bedroom Hall Vault Hall Vault Vault M. Bath M. Bath 9' Clg. 9' Clg. WIC WIC 9' Clg. 9' Clg. Tile Tub Shwr Covered Patio Kitchen WH 9' Clg. Vault WH Garage Garage 9' Clg. 9' Clg. Dining . Vault DW REF Master Master Bath Tub Bath Shower W Dining Utility Vault 9' Clg. D Master Bedroom W Vault Utility D Great Room 9' Clg. Bath Tile Vault 9' Clg. Shwr Hall Vault Hall Ceiling Change Vault Laundry 3/4 Bath M. Bath 9' Clg. Hall WIC 9' Clg. 9' Clg. Shwr Covered Patio insert Bedroom 2 Covered Patio 9' Clg. 9' Clg. XXX 9' Clg. 5080 Db'l Full Dining Lite Vault WH OPT Master Bedroom Vault Extended Patio Patio Door Garage Foyer 9' Clg. 12' Clg. Bath 9' Clg. Entry 12' Clg. Bedroom 3 9' Clg. Courtyard - Bedroom 3 Entry 9' Clg. 12' Clg. Courtyard WH WWW 3080 U Entry 3080 WH OPT Entry OPT Garage 9' Clg. 3 Car Garage 9' Clg. This drawing is conceptual only and for the convenience of reference. It should not be relied upon as a representation (express or implied), of the final size, location or dimensions of any lot, building, amenity, common space, or any other use. The developer expressly reserves the right, without notice or consent, T 9080 to make any modifications, revisions, and/or changes it deems desirable.