Enforcing Conformity: Criminalising Religiously Inspired Acts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report (2019)

MONITORING THE TREATMENT OF CHILDREN HELD IN ISRAELI MILITARY DETENTION ANNUAL REPORT – 2018/19 Date: 24 June 2019 Military Court Watch (MCW) is a registered non-profit organistion founded by a group of lawyers and other professionals from Israel, Palestine, Europe, the US and Australia with a belief in the rule of law. MCW is guided by the principle that all children detained by the Israeli military authorities are entitled to all the rights and protections guaranteed under international and other applicable laws. 2 Index Executive summary ....................................................................................... 3 Background .................................................................................................... 3 Detention figures ....................................................................................... 4 Current evidence of issues of concern .................................................. 6 Comparative Graph - Issues of Concern (2013-2016) ......................... 14 Recent developments ........................................................................... 15 Forcible transfer and unlawful detention ................................................... 16 Unlawful discrimination ............................................................................. 17 Accountability .......................................................................................... 19 A link between child detention and the settlements ........................................ 19 Recommendations .......................................................................................... -

Questions & Answers Paper No. 10

141 PROOF LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2015 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT _____________ QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS No. 10 TUESDAY 2 JUNE 2015 _____________ The Questions and Answers Paper is published at the end of each sitting day and will contain, by number and title, all unanswered questions, together with questions to which answers have been received on that sitting day and any new questions. Consequently the full text of any question will be printed only twice: when notice is given; and, when answered. During any adjournment of two weeks or more a Questions and Answers Paper will be published from time to time containing answers received. 142 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS Tuesday 2 June 2015 Publication of Questions Answer to be lodged by Q & A No. 1 (Including Question Nos 0001 to 0029) 09 June 2015 Q & A No. 2 (Including Question Nos 0030 to 0058) 10 June 2015 Q & A No. 3 (Including Question Nos 0059 to 0097) 11 June 2015 Q & A No. 4 (Including Question Nos 0098 to 0140) 16 June 2015 Q & A No. 5 (Including Question Nos 0141 to 0163) 17 June 2015 Q & A No. 6 (Including Question Nos 0164 to 0223) 18 June 2015 Q & A No. 7 (Including Question Nos 0224 to 0264) 30 June 2015 Q & A No. 8 (Including Question Nos 0265 to 0286) 01 July 2015 Q & A No. 9 (Including Question Nos 0287 to 0367) 02 July 2015 Q & A No. 10 (Including Question Nos 0368 to 0406) 07 July 2015 143 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS Tuesday 2 June 2015 5 MAY 2015 (Paper No. -

Lord Mayoral Minute Page 1

CITY OF NEWCASTLE Lord Mayoral Minute Page 1 ITEM-14 LMM 23/07/2019 - NSW LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION MOTION That City of Newcastle: 1. Congratulates Jodi McKay MP on her election as the NSW Leader of the Opposition, and Yasmin Catley MP, on her election as the NSW Deputy Leader of the Opposition; 2. Notes that both Jodi McKay MP and Yasmin Catley MP, have strong connections to Newcastle and the Hunter Region; 3. Welcomes the NSW Oppositions renewed focus on manufacturing and regional jobs; 4. Commits to working with both the NSW Government and the NSW Opposition to ensure City of Newcastle is at the forefront of the decision making in the State Parliament; 5. Consistent with recent correspondence to NSW Premier, the Hon. Gladys Berejiklian MP, and Prime Minister, the Hon. Scott Morrison MP, writes to the Leader of the Opposition requesting a meeting to outline City of Newcastle’s funding priorities at the state level. Background: New Labor Leadership elected 1 July 2019 New Labor leadership team has been elected with a historic focus on manufacturing and regional jobs. The new NSW Labor Leadership team has today been elected unopposed following a meeting of NSW Labor MPs. Swansea MP Yasmin Catley will serve as Deputy Labor Leader which marks the first time since the 1960s a regional representative has served in the leadership team of the NSW Labor Party (Jack Renshaw, Labor Premier 1964 – 1965, Member for Castlereagh). Adam Searle will continue as Leader of the Opposition in the NSW Upper House and Penny Sharpe will become Deputy Labor Leader in the Upper House. -

Policy Awareness Campaign Update: August/September

Policy awareness campaign update: August/September Misinformation continues about restrictions placed on children who are opted out of SRE Specifically, the misinformation centres on what activities can be undertaken by children not enrolled in scripture while scripture classes take place. Errors made relate to both the legislation and Department of Education (DoE) policy, and are made and disseminated in the procedures and supporting materials provided by DoE to schools and available on the DoE website. Legislation: The first misinformation relates to the legislation – specifically the NSW Education Act 1990 (No. 8). Often activists or commentators make the mistake of stating the prohibition on students attending non-scripture undertaking meaningful activities is enshrined in law. In fact, the law (Sections 32, 33, and 33A of the Act) does not restrict any learning or activities while other students attend scripture classes. Those restrictions are instead applied through the Department of Education’s policies. Policy: The second misinformation relates to the Religious Education Policy. The current policy does not restrict ethics classes taking place during periods when scripture is taught. Nor does it seek to restrict what children not participating in scripture are to be allowed to do. In 2010 DoE removed a discriminatory paragraph that declared children who were not in SRE were only able to engage in activities that: should neither compete with SRE nor be alternative lessons in the subjects within the curriculum or other areas, such as, ethics, values, civics or general religious education. This was replaced with this paragraph: Schools are to provide meaningful activities for students whose parents have withdrawn them from special religious education. -

Download the Annual Report 2019-2020

Leading � rec�very Annual Report 2019–2020 TARONGA ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 A SHARED FUTURE � WILDLIFE AND PE�PLE At Taronga we believe that together we can find a better and more sustainable way for wildlife and people to share this planet. Taronga recognises that the planet’s biodiversity and ecosystems are the life support systems for our own species' health and prosperity. At no time in history has this been more evident, with drought, bushfires, climate change, global pandemics, habitat destruction, ocean acidification and many other crises threatening natural systems and our own future. Whilst we cannot tackle these challenges alone, Taronga is acting now and working to save species, sustain robust ecosystems, provide experiences and create learning opportunities so that we act together. We believe that all of us have a responsibility to protect the world’s precious wildlife, not just for us in our lifetimes, but for generations into the future. Our Zoos create experiences that delight and inspire lasting connections between people and wildlife. We aim to create conservation advocates that value wildlife, speak up for nature and take action to help create a future where both people and wildlife thrive. Our conservation breeding programs for threatened and priority wildlife help a myriad of species, with our program for 11 Legacy Species representing an increased commitment to six Australian and five Sumatran species at risk of extinction. The Koala was added as an 11th Legacy Species in 2019, to reflect increasing threats to its survival. In the last 12 months alone, Taronga partnered with 28 organisations working on the front line of conservation across 17 countries. -

Life Education NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report I Have Fond Memories of the Friendly, Knowledgeable Giraffe

Life Education NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report I have fond memories of the friendly, knowledgeable giraffe. Harold takes you on a magical journey exploring and learning about healthy eating, our body - how it works and ways we can be active in order to stay happy and healthy. It gives me such joy to see how excited my daughter is to visit Harold and know that it will be an experience that will stay with her too. Melanie, parent, Turramurra Public School What’s inside Who we are 03 Our year Life Education is the nation’s largest not-for-profit provider of childhood preventative drug and health education. For 06 Our programs almost 40 years, we have taken our mobile learning centres and famous mascot – ‘Healthy Harold’, the giraffe – to 13 Our community schools, teaching students about healthy choices in the areas of drugs and alcohol, cybersafety, nutrition, lifestyle 25 Our people and respectful relationships. 32 Our financials OUR MISSION Empowering our children and young people to make safer and healthier choices through education. OUR VISION Generations of healthy young Australians living to their full potential. LIFE EDUCATION NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report Our year: Thank you for being part of Life Education NSW Together we worked to empower more children in NSW As a charity, we’re grateful for the generous support of the NSW Ministry of Health, and the additional funds provided by our corporate and community partners and donors. We thank you for helping us to empower more children in NSW this year to make good life choices. -

NTIA Letter Reopening 23082021

23 August 2021 The Hon. Gladys Berejiklian MP NSW Premier 52 Martin Place Sydney NSW 2000 CC: The Hon. Dominic Perrottet MP; The Hon. Brad Hazzard MP; The Hon. Victor Dominello MP; The Hon. Stuart Ayres MP; The Hon. Damien Tudehope MP; The Hon. Don Harwin MLC; The Hon. Natalie Ward MLC; The Hon. Mark Speakman MP; The Hon. Alex Greenwich MP; The Hon. Chris Minns MP; The Hon. Prue Carr MP; The Hon. John Graham MLC; The Hon. Penny Sharpe MLC; The Hon. Daniel Mookhey MLC; The Hon. Ryan Park MP; The Hon. Yasmin Catley MP; The Rt Hon the Lord Mayor of Sydney, Councillor Clover Moore Dear Premier Re: Reopening support for night time industries We write in furtherance of our letters dated 12 and 23 July 2021, with thanks for the support provided to the highly-impacted industries that the Night Time Industries Association (“NTIA”) represents - being hospitality, events and performance, arts, culture, retail and their supply chains. With public funds starting to find their way into private business bank accounts and the reintroduction of mandated rent relief for eligible commercial tenants - for which we thank you - we now turn our attention to the reopening of these industries as safely, efficiently and quickly as possible. In this, we are seeking more clarity on what the roadmap to recovery looks like, as well as reopening principles and support specifically targeted at these highly-impacted industries, which have experienced extreme adverse economic and personal impacts due to the lockdown. It is our understanding that confidence is at an all-time low since the onset of COVID-19. -

Our Year in Review 2017/18

our year in review 2017/18 A secure home for all www.shelternsw.org.au our year in review 01 02 03 04 About us Welcome & Our year Systemic p4 Reports in numbers advocacy p8 p14 p16 05 06 07 08 Shelter NSW Research Community Our history; Submissions p24 and NGO Champions of & Publications Education Change p23 p28 p34 10 11 12 09 Goodbye Our Members Financial Thank you Adam p42 Reports p36 p38 p44 Published in November 2018 by Shelter NSW ABN: 95 942 688 134 © Shelter NSW Incorporated Tel: (02) 9267 5733 [email protected] www.shelternsw.org.au 2 3 01 About Us Who we are Shelter NSW has been operating Our value proposition: since 1975 as the State’s peak housing and advocacy body Expertise Independence Working for • We research the causes • We promote and represent a fairer housing of inequity and injustice in broad interests across the system the housing system and housing system – we do Our vision advocate solutions that aim not represent landlords or • We aim to ensure that to make the housing system housing providers – we consumer voices are A secure home for all work towards delivering a do not represent specific included in our policy fairer housing system for all services – and we are not a development, review and tenant advocacy body responses • We know and understand the housing system • We provide systemic • We advocate to Our purpose advocacy and advice on Governments for change • We connect with policy and legislation for the in policy, legislation and stakeholders and consumers We pursue our vision through critical whole -

Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1

Tuesday, 4 August 2020 Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Tuesday, 4 August 2020 The Speaker (The Hon. Jonathan Richard O'Dea) took the chair at 12:00. The Speaker read the prayer and acknowledgement of country. [Notices of motions given.] Bills GAS LEGISLATION AMENDMENT (MEDICAL GAS SYSTEMS) BILL 2020 First Reading Bill introduced on motion by Mr Kevin Anderson, read a first time and printed. Second Reading Speech Mr KEVIN ANDERSON (Tamworth—Minister for Better Regulation and Innovation) (12:16:12): I move: That this bill be now read a second time. I am proud to introduce the Gas Legislation Amendment (Medical Gas Systems) Bill 2020. The bill delivers on the New South Wales Government's promise to introduce a robust and effective licensing regulatory system for persons who carry out medical gas work. As I said on 18 June on behalf of the Government in opposing the Hon. Mark Buttigieg's private member's bill, nobody wants to see a tragedy repeated like the one we saw at Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital. As I undertook then, the Government has taken the steps necessary to provide a strong, robust licensing framework for those persons installing and working on medical gases in New South Wales. To the families of John Ghanem and Amelia Khan, on behalf of the Government I repeat my commitment that we are taking action to ensure no other families will have to endure as they have. The bill forms a key part of the Government's response to licensed work for medical gases that are supplied in medical facilities in New South Wales. -

NSW Govt Lower House Contact List with Hyperlinks Sep 2019

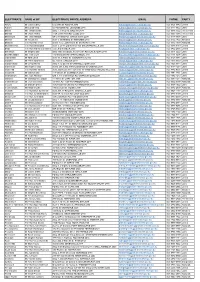

ELECTORATE NAME of MP ELECTORATE OFFICE ADDRESS EMAIL PHONE PARTY Albury Mr Justin Clancy 612 Dean St ALBURY 2640 [email protected] (02) 6021 3042 Liberal Auburn Ms Lynda Voltz 92 Parramatta Rd LIDCOMBE 2141 [email protected] (02) 9737 8822 Labor Ballina Ms Tamara Smith Shop 1, 7 Moon St BALLINA 2478 [email protected] (02) 6686 7522 The Greens Balmain Mr Jamie Parker 112A Glebe Point Rd GLEBE 2037 [email protected] (02) 9660 7586 The Greens Bankstown Ms Tania Mihailuk 9A Greenfield Pde BANKSTOWN 2200 [email protected] (02) 9708 3838 Labor Barwon Mr Roy Butler Suite 1, 60 Maitland St NARRABRI 2390 [email protected] (02) 6792 1422 Shooters Bathurst The Hon Paul Toole Suites 1 & 2, 229 Howick St BATHURST 2795 [email protected] (02) 6332 1300 Nationals Baulkham Hills The Hon David Elliott Suite 1, 25-33 Old Northern Rd BAULKHAM HILLS 2153 [email protected] (02) 9686 3110 Liberal Bega The Hon Andrew Constance 122 Carp St BEGA 2550 [email protected] (02) 6492 2056 Liberal Blacktown Mr Stephen Bali Shop 3063 Westpoint, Flushcombe Rd BLACKTOWN 2148 [email protected] (02) 9671 5222 Labor Blue Mountains Ms Trish Doyle 132 Macquarie Rd SPRINGWOOD 2777 [email protected] (02) 4751 3298 Labor Cabramatta Mr Nick Lalich Suite 10, 5 Arthur St CABRAMATTA 2166 [email protected] (02) 9724 3381 Labor Camden Mr Peter Sidgreaves 66 John St CAMDEN 2570 [email protected] (02) 4655 3333 Liberal -

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE – DD Month YYYY

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE – DD Month YYYY Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales Number 40 Wednesday, 1 May 2019 The New South Wales Government Gazette is the permanent public record of official NSW Government notices. It also contains local council, private and other notices. From 1 January 2019, each notice in the Government Gazette has a unique identifier that appears in round brackets at the end of the notice and that can be used as a reference for that notice (for example, (n2019-14)). The Gazette is compiled by the Parliamentary Counsel’s Office and published on the NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) under the authority of the NSW Government. The website contains a permanent archive of past Gazettes. To submit a notice for gazettal – see Gazette Information. By Authority ISSN 2201-7534 Government Printer NSW Government Gazette No 40 of 1 May 2019 pages 1280 to 1290 CERTIFICATE OF PERSONS RETURNED TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY NEW SOUTH WALES By His Excellency General The Honourable DAVID HURLEY, Companion of the Order of Australia, Distinguished Service Cross, (Retired), TO WIT Governor of the State of New South Wales in the Commonwealth of Australia DAVID HURLEY Governor I, General The Honourable DAVID HURLEY AC DSC (Ret’d), Governor of the State of New South Wales in the Commonwealth of Australia, do hereby certify and declare that the list appended hereto is the correct list, according to the certificates given by the Electoral Commissioner of New South Wales, of the names of the several persons returned for the Electoral Districts set against such names respectively at the General Election of Members to serve in the Legislative Assembly of New South Wales which was held on 23 March 2019; and I further certify that the several Writs of Election, being ninety-three in number, were duly returned by the day on which they were legally returnable. -

Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1

Tuesday, 22 May 2018 Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Tuesday, 22 May 2018 Presiding Officers ABSENCE OF THE SPEAKER The Clerk announced the absence of the Speaker. The Deputy Speaker (The Hon. Thomas George) took the chair at 12.00. The Deputy Speaker read the Prayer and acknowledgement of country Visitors VISITORS The DEPUTY SPEAKER: I extend a warm welcome to my guests Uday Huja, Jason Alcock, Dany Karam, Christopher Smith and Buddika Gunawardana, who are chefs from The Star visiting the Parliament today. [Notices of motions given.] Private Members' Statements TRIBUTE TO SUPERINTENDENT JULIAN GRIFFITHS Ms ELENI PETINOS (Miranda) (12:13): I rise to discuss and farewell the outgoing commander from the Sutherland Shire Police Area Command, Superintendent Julian Griffiths. Our local media has publicised that Superintendent Griffiths has been moved from the Sutherland Shire Police Area Command into the St George Police Area Command. Those of us who have had the opportunity to work with the superintendent, and to know him well, are going to miss him dearly. Media reports have not captured that Superintendent Griffiths is a capable and competent commander who has always been dedicated to serving the local community. He has done that in his capacity as a superintendent of both the Sutherland Shire Local Area Command and the merged Sutherland Shire Police Area Command over the past six years. I was recently told a story about Superintendent Griffiths which highlights the depth of his care and the lengths that he has gone to for the community. It is about the recent fires in the western part of the shire, in Menai, Alfords Point and Barden Ridge.