Annual Report (2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questions & Answers Paper No. 10

141 PROOF LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2015 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT _____________ QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS No. 10 TUESDAY 2 JUNE 2015 _____________ The Questions and Answers Paper is published at the end of each sitting day and will contain, by number and title, all unanswered questions, together with questions to which answers have been received on that sitting day and any new questions. Consequently the full text of any question will be printed only twice: when notice is given; and, when answered. During any adjournment of two weeks or more a Questions and Answers Paper will be published from time to time containing answers received. 142 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS Tuesday 2 June 2015 Publication of Questions Answer to be lodged by Q & A No. 1 (Including Question Nos 0001 to 0029) 09 June 2015 Q & A No. 2 (Including Question Nos 0030 to 0058) 10 June 2015 Q & A No. 3 (Including Question Nos 0059 to 0097) 11 June 2015 Q & A No. 4 (Including Question Nos 0098 to 0140) 16 June 2015 Q & A No. 5 (Including Question Nos 0141 to 0163) 17 June 2015 Q & A No. 6 (Including Question Nos 0164 to 0223) 18 June 2015 Q & A No. 7 (Including Question Nos 0224 to 0264) 30 June 2015 Q & A No. 8 (Including Question Nos 0265 to 0286) 01 July 2015 Q & A No. 9 (Including Question Nos 0287 to 0367) 02 July 2015 Q & A No. 10 (Including Question Nos 0368 to 0406) 07 July 2015 143 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS Tuesday 2 June 2015 5 MAY 2015 (Paper No. -

Policy Awareness Campaign Update: August/September

Policy awareness campaign update: August/September Misinformation continues about restrictions placed on children who are opted out of SRE Specifically, the misinformation centres on what activities can be undertaken by children not enrolled in scripture while scripture classes take place. Errors made relate to both the legislation and Department of Education (DoE) policy, and are made and disseminated in the procedures and supporting materials provided by DoE to schools and available on the DoE website. Legislation: The first misinformation relates to the legislation – specifically the NSW Education Act 1990 (No. 8). Often activists or commentators make the mistake of stating the prohibition on students attending non-scripture undertaking meaningful activities is enshrined in law. In fact, the law (Sections 32, 33, and 33A of the Act) does not restrict any learning or activities while other students attend scripture classes. Those restrictions are instead applied through the Department of Education’s policies. Policy: The second misinformation relates to the Religious Education Policy. The current policy does not restrict ethics classes taking place during periods when scripture is taught. Nor does it seek to restrict what children not participating in scripture are to be allowed to do. In 2010 DoE removed a discriminatory paragraph that declared children who were not in SRE were only able to engage in activities that: should neither compete with SRE nor be alternative lessons in the subjects within the curriculum or other areas, such as, ethics, values, civics or general religious education. This was replaced with this paragraph: Schools are to provide meaningful activities for students whose parents have withdrawn them from special religious education. -

Urgent Action

First UA: 161/19 Index: MDE 15/1445/2019 Israel/Occupied Palestinian Territories Date: 21 November 2019 URGENT ACTION NGO DIRECTOR IN ADMINISTRATIVE DETENTION Ubai Aboudi, NGO worker and education activist, has been issued a four-month administrative detention order by the Israeli military commander of the West Bank. Ubai Aboudi has been detained since 13 November 2019, without charge or trial in Ofer prison, near the West Bank city of Ramallah. TAKE ACTION: 1. Write a letter in your own words or using the sample below as a guide to one or both government officials listed. You can also email, fax, call or Tweet them. 2. Click here to let us know the actions you took on Urgent Action 161.19. It’s important to report because we share the total number with the officials we are trying to persuade and the people we are trying to help. Major-General Nadav Padan Ambassador Ron Dermer GOC Central Command Embassy of Israel Military Post 01149 3514 International Drive NW, Washington DC 20008 Battalion 877 Phone: 202 364 5500 Israel Email: [email protected] Fax: + 972 2 530 5741 Twitter: @IsraelinUSA @AmbDermer Email: [email protected] Facebook: @IsraelinUSA @ambdermer Instagram: @israelinusa Salutation: Dear Ambassador Dear Major-General Nadav Padan, On 13 November at around 3:00am at least 10 Israeli soldiers entered Ubai Aboudi’s home in Kufr Aqab and detained him in front of his wife and children. Ubai Aboudi is meant to take part in the Third International Meeting for Science in Palestine in the USA in January 2020. -

Israeli Occupation Forces Attacks on Journalists 2020 Palestinian Centre for Human Rights Palestinian Centre for Human Rights

Silencing the Press: Israeli Occupation Forces Attacks on Journalists 2020 Palestinian Centre for Human Rights Palestinian Centre for Human Rights Contents 4 Introduction 8 Legal Protection for Journalists under international humani- tarian law 11 Protection for press institutions and equipment 13 IOF’s violations against journalists working in local and inter- national media 13 I. Violations of the right to life and bodily integrity 27 II. Violence, assault, degrading and inhumane treatment against journalists 33 III. Detention and Arrests against Journalists 40 IV. Restrictions on the freedom of movement 2 Silencing the Press: Israeli Occupation Forces Attacks on Journalists 40 1. Journalists banned access to certain areas 41 2. Journalists banned travel outside the oPt 42 V. Media institutions raided, destroyed and shut 43 VI. Media offices bombarded and destroyed 43 VII. Newspapers banned in the OPT 44 Crimes without punishment 46 Conclusion and Recommendations 3 Palestinian Centre for Human Rights Israeli occupation forces (IOF) continued the systematic attacks 1 Introduction against local and international media personnel working in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) despite the protection that journalists, as civilians, enjoy under international law. IOF grave vi- olations against journalists include threats to their personal safety and attack on their equipment with live and rubber bullets, phys- ical and emotional assault, restrictions on the freedom of move- ment, bombardment of their office and other violations demon- strating a well-planned scheme to isolate the oPt from the rest of the world and to provide cover-up for crimes against civilians, and impose a narrative opposite to the reality on the ground.2 This is the 22nd edition of the “Silencing the Press” series issued by the Palestinian Center for Human Rights (PCHR). -

A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Map .................................................................................................................................. i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution ................................................................................. -

Alleged Arbitrary Arrest, Enforced Disappearance and Death of Mr. Saleh Barghouthi

PALAIS DES NATIONS - 1211 GENEV A 10, SWITZERLAND Mandates of the Working Group on Arbitraiy Detention; the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances; the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967; and the Special Rapporteur on the proniotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countertng terrorism REFERENCE UA ISR 2/2019 30 Januaiy 2019 Excellency, We liave the lionour to address you in our capacity as Working Group on Arbitrary Detention; Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances; Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967; and Special Rapporteur on tlie promotion and protection of human riglits and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, pursuant to Human Riglits Council resolutions 33/30, 36/6, 35/15, 1993/2A and 31/3. In this connection, we would like to bring to the attention of your Excellency's Government infornnation we have received concerning the alleged arbitrary arrest, detention, enforced disappearance and death of Mr. Saleh Omar Barghouthi and subsequent punitive measures imposed on his family since 12 December 2018. According to the information received: Alleged arbitrary arrest, enforced disappearance and death of Mr. Saleh Barghouthi On Wednesday 12 December 2018, between 6.40 and 7.00 p.m., Mr. Saleh Omar Barghouthi, a 29 year-old Palestinian taxi driver, was driving on the road leading to Birzeit, near Surda town, Nortli of Ramallah, in the Occupied West Bank, when he was hit by a blue SsangYong jeep with a Palestinian license plate, which was following his car. -

You Can Download the NSW Caring Fairly Toolkit Here!

A TOOLKIT: How carers in NSW can advocate for change www.caringfairly.org.au Caring Fairly is represented in NSW by: www.facebook.com/caringfairlycampaign @caringfairly @caringfairly WHO WE ARE Caring Fairly is a national campaign led by unpaid carers and specialist organisations that support and advocate for their rights. Launched in August 2018 and coordinated by Mind Australia, Caring Fairly is led by a coalition of over 25 carer support organisations, NGOs, peak bodies, and carers themselves. In NSW, Caring Fairly is represented by Mental Health Carers NSW, Carers NSW and Flourish Australia. We need your support, and invite you to join the Caring Fairly coalition. Caring Fairly wants: • A fairer deal for Australia’s unpaid carers • Better economic outcomes for people who devote their time to supporting and caring for their loved ones • Government policies that help unpaid carers balance paid work and care, wherever possible • Politicians to understand what’s at stake for unpaid carers going into the 2019 federal election To achieve this, we need your help. WHY WE ARE TAKING ACTION Unpaid carers are often hidden from view in Australian politics. There are almost 2.7 million unpaid carers nationally. Over 850,000 people in Australia are the primary carer to a loved one with disability. Many carers, understandly, don’t identify as a ‘carer’. Caring Fairly wants visibility for Australia’s unpaid carers. We are helping to build a new social movement in Australia to achieve this. Unpaid carers prop up Australian society. Like all Australians, unpaid carers have a right to a fair and decent quality of life. -

Updateaug 2021 Vol 29, No

UpdateAug 2021 Vol 29, No. 2 Three times a year Newsletter The thing about Bluey Dr Cheryl Hayden Member of ABC Friends, Queensland s exposed recently by Amanda Meade in The Guardian Bluey is an on 14 May, the Morrison government has employed its endearing rendition A endless sleight of hand with language to imply that it had of a world in funded the Emmy Award-winning children’s animation, Bluey, which the human through the Australian Children’s Television Foundation. The population is depicted by various breeds of dog. Bluey herself is office of Communications Minister, Paul Fletcher, had apparently a pre-schooler, the elder daughter of perhaps the world’s best not consulted with the Foundation when making this claim and, parents, Bandit and Chilli Heeler, and sister to Bingo. Yes, they as The Guardian explained, refused to accept that an error or a are a family of blue and red heeler dogs, with an extended family misleading comment had been made. Instead, his spokesperson of Heeler aunts, uncles, grandparents and cousins. They live came up with the lame comment that while the Foundation did on a hilltop in Brisbane’s inner-city Paddington, in a renovated not directly fund the program, it was “a strong advocate for quality Queenslander. Go on adventures with them, and you’ll find children’s content including actively supporting the success of yourself eating ice-cream at Southbank, shopping in the Myer Bluey through lots of positive endorsement and publicity, as Centre, or hopping on river rocks in a local creek. an excellent example of Australian’s children’s content, [and] Bluey and Bingo have a diverse bunch of friends, and the wit and the government is proud that it has been able to support the irony that has gone into developing their names and characters production of Bluey through the ABC and Screen Australia.” is hard to miss. -

Defenceless: the Impact of the Israeli Military Detention System On

DEFENCELESS The impact of the Israeli military detention system on Palestinian children Contents Foreword 3 Executive summary 4 Methodology 8 West Bank context 9 Overview of the Israeli military detention system 9 International legal context 12 Children’s experience of the detention system 14 The moment of arrest or detention 14 Transfer 15 Interrogation 15 Detention 17 Denial of services 18 The impact of detention on children 20 Mental health 20 Behavioural changes 21 Coping mechanisms 22 Physical health 22 Family and community impact 23 Isolation 23 Normalisation of the detention of children 24 ‘Heroisation’ 25 Education 26 Recovery and reintegration 27 Looking to the future 27 Save the Children’s response 28 Recommendations for action 29 Please note that all names contained All the drawings that appear in this report have been created within this report have been changed by young people who were detained or arrested as children. for the protection of the individuals. They were asked to portray their experiences in detention. 2 Foreword An Israeli boy throws a stone from a settlement at In 2011 I was one of a group of nine British lawyers a Palestinian child. In the unlikely event that he is who, with Foreign Office sponsorship, went to Israel arrested, he will be bailed. If he is questioned, it will and the West Bank to examine the legal aspects of be with full safeguards. If he is prosecuted, it will be Israel’s practice of detaining Palestinian children, before a juvenile court, with his parents and a lawyer girls as well as boys, in military custody. -

No Minor Matter

בצלם - מרכז המידע הישראלי לזכויות האדם בשטחים (ע.ר.) B’Tselem – The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories No Minor Matter Violation of the Rights of Palestinian Minors Arrested by Israel on Suspicion of Stone-Throwing July 2011 רחוב התעשייה ,8 ת.ד. 53132, ירושלים 91531, טלפון 6735599 (02), פקס 6749111 (02) 8 Hata’asiya St. (4th Floor), P.O.Box 53132, Jerusalem 91531, Tel. (02) 6735599, Fax (02) 6749111 [email protected] http://www.btselem.org Written and researched by Naama Baumgarten‐Sharon Edited by Yael Stein Translated by Zvi Shulman English editing by Maya Johnston Data coordination by Noam Raz and Noam Preiss Field work by Karim Jubran, Salma a-Deb’i, Musa Abu Hashhash, 'Atef Abu a-Rub, Suha Zeid, Iyad Hadad, ‘Abd al-Karim Sa’adi, and ‘Amer ‘Aruri B’Tselem thanks Adv. Gaby Lasky, Adv. Neri Ramati and Adv. Limor Goldstein, as well as Adv. Iyad Misk and the DCI-Palestine organization. 2 Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 1: Minors in criminal proceedings – legal background ............................................................ 7 International law...................................................................................................................................... 7 Israeli law.................................................................................................................................................. 9 Military -

Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1

Tuesday, 4 August 2020 Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Tuesday, 4 August 2020 The Speaker (The Hon. Jonathan Richard O'Dea) took the chair at 12:00. The Speaker read the prayer and acknowledgement of country. [Notices of motions given.] Bills GAS LEGISLATION AMENDMENT (MEDICAL GAS SYSTEMS) BILL 2020 First Reading Bill introduced on motion by Mr Kevin Anderson, read a first time and printed. Second Reading Speech Mr KEVIN ANDERSON (Tamworth—Minister for Better Regulation and Innovation) (12:16:12): I move: That this bill be now read a second time. I am proud to introduce the Gas Legislation Amendment (Medical Gas Systems) Bill 2020. The bill delivers on the New South Wales Government's promise to introduce a robust and effective licensing regulatory system for persons who carry out medical gas work. As I said on 18 June on behalf of the Government in opposing the Hon. Mark Buttigieg's private member's bill, nobody wants to see a tragedy repeated like the one we saw at Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital. As I undertook then, the Government has taken the steps necessary to provide a strong, robust licensing framework for those persons installing and working on medical gases in New South Wales. To the families of John Ghanem and Amelia Khan, on behalf of the Government I repeat my commitment that we are taking action to ensure no other families will have to endure as they have. The bill forms a key part of the Government's response to licensed work for medical gases that are supplied in medical facilities in New South Wales. -

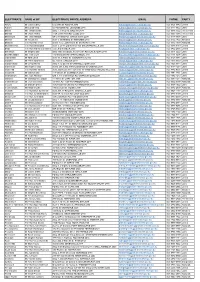

NSW Govt Lower House Contact List with Hyperlinks Sep 2019

ELECTORATE NAME of MP ELECTORATE OFFICE ADDRESS EMAIL PHONE PARTY Albury Mr Justin Clancy 612 Dean St ALBURY 2640 [email protected] (02) 6021 3042 Liberal Auburn Ms Lynda Voltz 92 Parramatta Rd LIDCOMBE 2141 [email protected] (02) 9737 8822 Labor Ballina Ms Tamara Smith Shop 1, 7 Moon St BALLINA 2478 [email protected] (02) 6686 7522 The Greens Balmain Mr Jamie Parker 112A Glebe Point Rd GLEBE 2037 [email protected] (02) 9660 7586 The Greens Bankstown Ms Tania Mihailuk 9A Greenfield Pde BANKSTOWN 2200 [email protected] (02) 9708 3838 Labor Barwon Mr Roy Butler Suite 1, 60 Maitland St NARRABRI 2390 [email protected] (02) 6792 1422 Shooters Bathurst The Hon Paul Toole Suites 1 & 2, 229 Howick St BATHURST 2795 [email protected] (02) 6332 1300 Nationals Baulkham Hills The Hon David Elliott Suite 1, 25-33 Old Northern Rd BAULKHAM HILLS 2153 [email protected] (02) 9686 3110 Liberal Bega The Hon Andrew Constance 122 Carp St BEGA 2550 [email protected] (02) 6492 2056 Liberal Blacktown Mr Stephen Bali Shop 3063 Westpoint, Flushcombe Rd BLACKTOWN 2148 [email protected] (02) 9671 5222 Labor Blue Mountains Ms Trish Doyle 132 Macquarie Rd SPRINGWOOD 2777 [email protected] (02) 4751 3298 Labor Cabramatta Mr Nick Lalich Suite 10, 5 Arthur St CABRAMATTA 2166 [email protected] (02) 9724 3381 Labor Camden Mr Peter Sidgreaves 66 John St CAMDEN 2570 [email protected] (02) 4655 3333 Liberal