Dopminergic Treatment of Treatment Refractory Mood Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minimum Laboratory Monitoring for Psychotropic Medications

Minimum Laboratory Monitoring For Psychotropic Medications ANTIPSYCHOTIC MEDICATIONS GENERIC BRAND GENERIC BRAND Aripiprazole Abilify, Abilify Olanzapine Zyprexa, Zyprexa Zydis Maintena, Aristada Asenapine Saphris Paliperidone Invega, Invega Sustenna, Invega Trinza Brexpiprazole Rexulti Perphenazine Trilafon Cariprazine Vraylar Pimozide Orap Chlorpromazine Thorazine Quetiapine Seroquel, Seroquel XR Clozapine Clozaril, Fazaclo Risperidone Risperdal, Risperdal Consta, Risperdal M Tabs Fluphenazine, Fluphenazine D Prolixin, Prolixin D Thioridazine Mellaril Haloperidol, Haloperidol D Haldol, Haldol D Thiothixene Navane Iloperidone Fanapt Trifluoperazine Stelazine Loxapine Loxitane Ziprasidone Geodon Lurasidone Latuda MONITORING ANTIPSYCHOTIC FREQUENCY OF MONITORING AIMS (Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale) On initiation of any antipsychotic medication and at least every six months thereafter, or more frequently as clinically indicated. ABDOMINAL GIRTH (>18 years old) For individuals at least 18 years old, on initiation of any medication and at least every six months thereafter, or more frequently as clinically indicated. WEIGHT & BODY MASS INDEX (BMI) On initiation of any medication and at least every six months thereafter, or more frequently as clinically indicated. HEART RATE & BLOOD PRESSSURE On initiation of any medication and at least every six months thereafter, or more frequently as clinically indicated. COMPREHENSIVE METABOLIC PANEL (CMP), On initiation of any medication affecting this parameter and at least annually LIPIDS, FASTING -

Eslicarbazepine Acetate: a New Improvement on a Classic Drug Family for the Treatment of Partial-Onset Seizures

Drugs R D DOI 10.1007/s40268-017-0197-5 REVIEW ARTICLE Eslicarbazepine Acetate: A New Improvement on a Classic Drug Family for the Treatment of Partial-Onset Seizures 1 1 1 Graciana L. Galiana • Angela C. Gauthier • Richard H. Mattson Ó The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Eslicarbazepine acetate is a new anti-epileptic drug belonging to the dibenzazepine carboxamide family Key Points that is currently approved as adjunctive therapy and monotherapy for partial-onset (focal) seizures. The drug Eslicarbazepine acetate is an effective and safe enhances slow inactivation of voltage-gated sodium chan- treatment option for partial-onset seizures as nels and subsequently reduces the activity of rapidly firing adjunctive therapy and monotherapy. neurons. Eslicarbazepine acetate has few, but some, drug– drug interactions. It is a weak enzyme inducer and it Eslicarbazepine acetate improves upon its inhibits cytochrome P450 2C19, but it affects a smaller predecessors, carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine, by assortment of enzymes than carbamazepine. Clinical being available in a once-daily regimen, interacting studies using eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive treat- with a smaller range of drugs, and causing less side ment or monotherapy have demonstrated its efficacy in effects. patients with refractory or newly diagnosed focal seizures. The drug is generally well tolerated, and the most common side effects include dizziness, headache, and diplopia. One of the greatest strengths of eslicarbazepine acetate is its ability to be administered only once per day. Eslicar- 1 Introduction bazepine acetate has many advantages over older anti- epileptic drugs, and it should be strongly considered when Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder affecting over treating patients with partial-onset epilepsy. -

Drug Use Evaluation: Antipsychotic Utilization in Schizophrenia Patients

© Copyright 2012 Oregon State University. All Rights Reserved Drug Use Research & Management Program Oregon State University, 500 Summer Street NE, E35 Salem, Oregon 97301-1079 Phone 503-947-5220 | Fax 503-947-1119 Drug Use Evaluation: Antipsychotic Utilization in Schizophrenia Patients Research Questions: 1. How many schizophrenia patients are prescribed recommended first-line second-generation treatments for schizophrenia? 2. How many schizophrenia patients switch to an injectable antipsychotic after stabilization on an oral antipsychotic? 3. How many schizophrenia patients are prescribed 2 or more concomitant antipsychotics? 4. Are claims for long-acting injectable antipsychotics primarily billed as pharmacy or physician administered claims? 5. Does adherence to antipsychotic therapy differ between patients with claims for different routes of administration (oral vs. long-acting injectable)? Conclusions: In total, 4663 schizophrenia patients met inclusion criteria, and approximately 14% of patients (n=685) were identified as treatment naïve without claims for antipsychotics in the year before their first antipsychotic prescription. Approximately 45% of patients identified as treatment naïve had a history of remote antipsychotic use, but it is unclear if antipsychotics were historically prescribed for schizophrenia. Oral second-generation antipsychotics which are recommended as first-line treatment in the MHCAG schizophrenia algorithm were prescribed as initial treatment in 37% of treatment naive patients and 28% of all schizophrenia patients. Recommended agents include risperidone, paliperidone, and aripiprazole. Utilization of parenteral antipsychotics was limited in patients with schizophrenia. Overall only 8% of patients switched from an oral to an injectable therapy within 6 months of their first claim. Approximately, 60% of all schizophrenia patients (n=2512) had claims for a single antipsychotic for at least 12 continuous weeks and may be eligible to transition to a long-acting injectable antipsychotic. -

Schizophrenia Care Guide

August 2015 CCHCS/DHCS Care Guide: Schizophrenia SUMMARY DECISION SUPPORT PATIENT EDUCATION/SELF MANAGEMENT GOALS ALERTS Minimize frequency and severity of psychotic episodes Suicidal ideation or gestures Encourage medication adherence Abnormal movements Manage medication side effects Delusions Monitor as clinically appropriate Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Danger to self or others DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA/EVALUATION (PER DSM V) 1. Rule out delirium or other medical illnesses mimicking schizophrenia (see page 5), medications or drugs of abuse causing psychosis (see page 6), other mental illness causes of psychosis, e.g., Bipolar Mania or Depression, Major Depression, PTSD, borderline personality disorder (see page 4). Ideas in patients (even odd ideas) that we disagree with can be learned and are therefore not necessarily signs of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is a world-wide phenomenon that can occur in cultures with widely differing ideas. 2. Diagnosis is made based on the following: (Criteria A and B must be met) A. Two of the following symptoms/signs must be present over much of at least one month (unless treated), with a significant impact on social or occupational functioning, over at least a 6-month period of time: Delusions, Hallucinations, Disorganized Speech, Negative symptoms (social withdrawal, poverty of thought, etc.), severely disorganized or catatonic behavior. B. At least one of the symptoms/signs should be Delusions, Hallucinations, or Disorganized Speech. TREATMENT OPTIONS MEDICATIONS Informed consent for psychotropic -

Chapter 25 Mechanisms of Action of Antiepileptic Drugs

Chapter 25 Mechanisms of action of antiepileptic drugs GRAEME J. SILLS Department of Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology, University of Liverpool _________________________________________________________________________ Introduction The serendipitous discovery of the anticonvulsant properties of phenobarbital in 1912 marked the foundation of the modern pharmacotherapy of epilepsy. The subsequent 70 years saw the introduction of phenytoin, ethosuximide, carbamazepine, sodium valproate and a range of benzodiazepines. Collectively, these compounds have come to be regarded as the ‘established’ antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). A concerted period of development of drugs for epilepsy throughout the 1980s and 1990s has resulted (to date) in 16 new agents being licensed as add-on treatment for difficult-to-control adult and/or paediatric epilepsy, with some becoming available as monotherapy for newly diagnosed patients. Together, these have become known as the ‘modern’ AEDs. Throughout this period of unprecedented drug development, there have also been considerable advances in our understanding of how antiepileptic agents exert their effects at the cellular level. AEDs are neither preventive nor curative and are employed solely as a means of controlling symptoms (i.e. suppression of seizures). Recurrent seizure activity is the manifestation of an intermittent and excessive hyperexcitability of the nervous system and, while the pharmacological minutiae of currently marketed AEDs remain to be completely unravelled, these agents essentially redress the balance between neuronal excitation and inhibition. Three major classes of mechanism are recognised: modulation of voltage-gated ion channels; enhancement of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-mediated inhibitory neurotransmission; and attenuation of glutamate-mediated excitatory neurotransmission. The principal pharmacological targets of currently available AEDs are highlighted in Table 1 and discussed further below. -

Current P SYCHIATRY

Current p SYCHIATRY N ew Investigators Tips to manage and prevent discontinuation syndromes Informed tapering can protect patients when you stop a medication Sriram Ramaswamy, MD Shruti Malik, MBBS, MHSA Vijay Dewan, MD Instructor, department of psychiatry Foreign medical graduate Assistant professor Creighton University Department of psychiatry Omaha, NE University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, NE bruptly stopping common psychotropics New insights on psychotropic A —particularly antidepressants, benzodi- drug safety and side effects azepines, or atypical antipsychotics—can trigger a discontinuation syndrome, with: This paper was among those entered in the 2005 • rebound or relapse of original symptoms Promising New Investigators competition sponsored • uncomfortable new physical and psycho- by the Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Information Service (NMSIS). The theme of this year’s competition logical symptoms was “New insights on psychotropic drug safety and • physiologic withdrawal at times. side effects.” To increase health professionals’ awareness of URRENT SYCHIATRY 1 C P is honored to publish this peer- the risk of these adverse effects, this article reviewed, evidence-based article on a clinically describes discontinuation syndromes associated important topic for practicing psychiatrists. with various psychotropics and offers strategies to NMSIS is dedicated to reducing morbidity and anticipate, recognize, and manage them. mortality of NMS by improving medical and psychiatric care of patients with heat-related disorders; providing -

Clinical Review, Adverse Events

Clinical Review, Adverse Events Drug: Carbamazepine NDA: 16-608, Tegretol 20-712, Carbatrol 21-710, Equetro Adverse Event: Stevens-Johnson Syndrome Reviewer: Ronald Farkas, MD, PhD Medical Reviewer, DNP, ODE I 1. Executive Summary 1.1 Background Carbamazepine (CBZ) is an anticonvulsant with FDA-approved indications in epilepsy, bipolar disorder and neuropathic pain. CBZ is associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN), closely related serious cutaneous adverse drug reactions that can be permanently disabling or fatal. Other anticonvulsants, including phenytoin, phenobarbital, and lamotrigine are also associated with SJS/TEN, as are members of a variety of other drug classes, including nonsteriodal anti-inflammatory drugs and sulfa drugs. The incidence of CBZ-associated SJS/TEN has been considered “extremely rare,” as noted in current U.S. drug labeling. However, recent publications and postmarketing data suggest that CBZ- associated SJS/TEN occurs at a much higher rate in some Asian populations, about 2.5 cases per 1,000 new exposures, and that most of this increased risk is in individuals carrying a specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allele, HLA-B*1502. This HLA-B allele is present in about 5- to 20% of many, but not all, Asian populations, and is also present in about 2- to 4% of South Asians/Indians. The allele is also present at a lower frequency, < 1%, in several other ethnic groups around the world (although likely due to distant Asian ancestry). About 10% of U.S. Asians carry HLA-B*1502. HLA-B*1502 is generally not present in the U.S. -

Lithium Sulfate

SIGMA-ALDRICH sigma-aldrich.com Material Safety Data Sheet Version 4.1 Revision Date 09/14/2012 Print Date 03/12/2014 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product name : Lithium sulfate Product Number : 203653 Brand : Aldrich Supplier : Sigma-Aldrich 3050 Spruce Street SAINT LOUIS MO 63103 USA Telephone : +1 800-325-5832 Fax : +1 800-325-5052 Emergency Phone # (For : (314) 776-6555 both supplier and manufacturer) Preparation Information : Sigma-Aldrich Corporation Product Safety - Americas Region 1-800-521-8956 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Emergency Overview OSHA Hazards Target Organ Effect, Harmful by ingestion. Target Organs Central nervous system, Kidney, Cardiovascular system. GHS Classification Acute toxicity, Oral (Category 4) GHS Label elements, including precautionary statements Pictogram Signal word Warning Hazard statement(s) H302 Harmful if swallowed. Precautionary none statement(s) HMIS Classification Health hazard: 1 Chronic Health Hazard: * Flammability: 0 Physical hazards: 0 NFPA Rating Health hazard: 1 Fire: 0 Reactivity Hazard: 0 Potential Health Effects Inhalation May be harmful if inhaled. May cause respiratory tract irritation. Aldrich - 203653 Page 1 of 7 Skin Harmful if absorbed through skin. May cause skin irritation. Eyes May cause eye irritation. Ingestion Harmful if swallowed. 3. COMPOSITION/INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS Formula : Li2O4S Molecular Weight : 109.94 g/mol Component Concentration Lithium sulphate CAS-No. 10377-48-7 - EC-No. 233-820-4 4. FIRST AID MEASURES General advice Move out of dangerous area.Consult a physician. Show this safety data sheet to the doctor in attendance. If inhaled If breathed in, move person into fresh air. If not breathing, give artificial respiration. Consult a physician. -

Neuroenhancement in Healthy Adults, Part I: Pharmaceutical

l Rese ca arc ni h li & C f B o i o l e Journal of a t h n Fond et al., J Clinic Res Bioeth 2015, 6:2 r i c u s o J DOI: 10.4172/2155-9627.1000213 ISSN: 2155-9627 Clinical Research & Bioethics Review Article Open Access Neuroenhancement in Healthy Adults, Part I: Pharmaceutical Cognitive Enhancement: A Systematic Review Fond G1,2*, Micoulaud-Franchi JA3, Macgregor A2, Richieri R3,4, Miot S5,6, Lopez R2, Abbar M7, Lancon C3 and Repantis D8 1Université Paris Est-Créteil, Psychiatry and Addiction Pole University Hospitals Henri Mondor, Inserm U955, Eq 15 Psychiatric Genetics, DHU Pe-psy, FondaMental Foundation, Scientific Cooperation Foundation Mental Health, National Network of Schizophrenia Expert Centers, F-94000, France 2Inserm 1061, University Psychiatry Service, University of Montpellier 1, CHU Montpellier F-34000, France 3POLE Academic Psychiatry, CHU Sainte-Marguerite, F-13274 Marseille, Cedex 09, France 4 Public Health Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, EA 3279, F-13385 Marseille, Cedex 05, France 5Inserm U1061, Idiopathic Hypersomnia Narcolepsy National Reference Centre, Unit of sleep disorders, University of Montpellier 1, CHU Montpellier F-34000, Paris, France 6Inserm U952, CNRS UMR 7224, Pierre and Marie Curie University, F-75000, Paris, France 7CHU Carémeau, University of Nîmes, Nîmes, F-31000, France 8Department of Psychiatry, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Campus Benjamin Franklin, Eschenallee 3, 14050 Berlin, Germany *Corresponding author: Dr. Guillaume Fond, Pole de Psychiatrie, Hôpital A. Chenevier, 40 rue de Mesly, Créteil F-94010, France, Tel: (33)178682372; Fax: (33)178682381; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: January 06, 2015, Accepted date: February 23, 2015, Published date: February 28, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Fond G, et al. -

Management and Treatment of Lithium-Induced Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus

REVIEW Management and treatment of lithium- induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus Christopher K Finch†, Lithium carbonate is a well documented cause of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, with as Tyson WA Brooks, many as 10 to 15% of patients taking lithium developing this condition. Clinicians have Peggy Yam & Kristi W Kelley been well aware of lithium toxicity for many years; however, the treatment of this drug- induced condition has generally been remedied by discontinuation of the medication or a †Author for correspondence Methodist University reduction in dose. For those patients unresponsive to traditional treatment measures, Hospital, Department several pharmacotherapeutic regimens have been documented as being effective for the of Pharmacy, University of management of lithium-induced diabetes insipidus including hydrochlorothiazide, Tennessee, College of Pharmacy, 1265 Union Ave., amiloride, indomethacin, desmopressin and correction of serum lithium levels. Memphis, TN 38104, USA Tel.: +1 901 516 2954 Fax: +1 901 516 8178 [email protected] Lithium carbonate is well known for its wide use associated with a mutation(s) of vasopressin in bipolar disorders due to its mood stabilizing receptors. Acquired causes are tubulointerstitial properties. It is also employed in aggression dis- disease (e.g., sickle cell disease, amyloidosis, orders, post-traumatic stress disorders, conduct obstructive uropathy), electrolyte disorders (e.g., disorders and even as adjunctive therapy in hypokalemia and hypercalcemia), pregnancy, or depression. Lithium has many well documented conditions induced by a drug (e.g., lithium, adverse effects as well as a relatively narrow ther- demeclocycline, amphotericin B and apeutic range of 0.4 to 0.8 mmol/l. Clinically vincristine) [3,4]. Lithium is the most common significant adverse effects include polyuria, mus- cause of drug-induced nephrogenic DI [5]. -

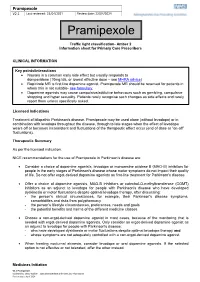

Pramipexole V2.1 Last Reviewed: 22/04/2021 Review Date: 22/04/2024

Pramipexole V2.1 Last reviewed: 22/04/2021 Review date: 22/04/2024 Pramipexole Traffic light classification- Amber 2 Information sheet for Primary Care Prescribers CLINICAL INFORMATION Key points/interactions Nausea is a common early side effect but usually responds to domperidone (10mg tds, or lowest effective dose – see MHRA advice) Ropinirole MR is first line dopamine agonist. Pramipexole MR should be reserved for patients in whom this is not suitable- see formulary. Dopamine agonists may cause compulsive/addictive behaviours such as gambling, compulsive shopping and hyper sexuality. Patients rarely recognise such changes as side effects and rarely report them unless specifically asked. Licensed Indications Treatment of idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Pramipexole may be used alone (without levodopa) or in combination with levodopa throughout the disease, through to late stages when the effect of levodopa wears off or becomes inconsistent and fluctuations of the therapeutic effect occur (end of dose or “on-off” fluctuations). Therapeutic Summary As per the licensed indication. NICE recommendations for the use of Pramipexole in Parkinson’s disease are: Consider a choice of dopamine agonists, levodopa or monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors for people in the early stages of Parkinson's disease whose motor symptoms do not impact their quality of life. Do not offer ergot-derived dopamine agonists as first-line treatment for Parkinson's disease. Offer a choice of dopamine agonists, MAO-B inhibitors or catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) -

Should Inverse Agonists Be Defined by Pharmacological Mechanism Or

CNS Spectrums,(2019), 24 419 – 425. © Cambridge University Press 2018. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S1092852918000986 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Switching stable patients with schizophrenia from their oral antipsychotics to aripiprazole lauroxil: a post hoc safety analysis of the initial 12-week crossover period Peter J. Weiden,1* Yangchun Du,2 Chih-Chin Liu,2 and Arielle D. Stanford3 1 Medical Affairs, Alkermes, Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA 2 Clinical Development, Alkermes, Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA 3 Clinical Science, Alkermes, Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA Objective. Switching antipsychotic medications is common in patients with schizophrenia who are experiencing persistent symptoms or tolerability issues associated with their current drug regimen. This analysis assessed the safety of switching from an oral antipsychotic to the long-acting injectable antipsychotic aripiprazole lauroxil (AL). Methods. This was a post hoc analysis of outpatients with schizophrenia who were prescribed an oral antipsychotic and who enrolled in an international, open-label, long-term (52-week) safety study of AL. The analysis focused on the first 3 injections of AL 882 mg over 12 weeks, divided into the immediate 4-week crossover period between the first and second AL injections (initiation phase) and the subsequent 8 weeks (stabilization phase). Patients were grouped by preswitch oral antipsychotic medication, and safety and clinical symptoms were assessed. Results. In total, 190 patients had switched from one of the following oral antipsychotic medications: aripiprazole, conventional antipsychotics, risperidone/paliperidone, olanzapine, or quetiapine.