Constructing and Navigating Autonomous Self-Organization: Notes and Experiences from Community Struggles in Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ricardo Flores Magón and the Transnational Anarchists in Los Angeles, 1900-1922

Ricardo Flores Magón and the Transnational Anarchists in Los Angeles, 1900-1922 Sergio Maldonado In the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution, many people such as Ricardo Flores Magón and the residents of Los Angeles found themselves in a perpetual state of exploitation by either the Mexican or U.S. governments. Mexicans found solidarity together, mounting resistance against insurmountable odds. Even under the direst of circumstances, their efforts in the early twentieth- century would propel Mexican-Americans’ identity into an epoch of self-realization that is uniquely transnational. For many Mexican-Americans in this period, Ricardo Flores Magón was their inspiration. In 1917 Flores Magón gave a speech in front of a group of Mexicans from the California cities of El Monte and La Puente, commemorating the manifesto of El Partido Liberal Mexicano. After years of struggle against the Mexican dictatorship, he explained to his comrades that they must leave behind the clasping of hands and anxiously asking ourselves what will be effective in resisting the assault of governmental tyranny and capitalist exploitation. The remedy is in our hands: that all who suffer the same evils unite, certain that before our solidity the abuses of those who base their strength in our separations and indifference will crumble. 1 This and similar calls for unity by Flores Magón and the many Mexicans residing in and around Los Angeles who flocked to listen to him together fostered the growth of Chicano nationalism. Flores Magón was a renowned anarchist intellectual of the Mexican Revolution. Many scholars have regarded him as an important figure in Chicano history and view him as a fundamental figure of Chicano nationalism due to his rebellious actions in Mexico and the United States. -

Jóvenes, Globalización Y Movimientos Altermundistas 76

cubierta INJUVE n…76 ok 4C 24/4/07 11:39 P gina 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 76 ≥ Marzo 07 REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS DE REVISTA JUVENTUD DE ≥ Marzo 07 | Nº 76 76 Jóvenes, globalización Jóvenes, globalización y movimientos altermundistas y movimientos altermundistas Si cada fase histórica tiene sus temas centrales de discusión, parece ser que el siglo que estamos comenzando condensa en el término globalización buena parte de sus preocupaciones y temores, también de sus esperanzas. Las aportaciones que integran este número pretenden sumarse al proceso de reflexión sobre la globalización en curso. Son ya muchos los estudios que se ocupan de investigar los aspectos más diversos de un fenómeno tan complejo y poliédrico como este. Nuestra particular contribución consiste en ofrecer un examen amplio y detallado del Movimiento Antiglobalización o Alterglobalizador, con especial atención a las nuevas formas de organización y acción promovidas por las nuevas generaciones que participan en el Movimiento Global. Los primeros artículos están dedicados a caracterizar al “Movimiento de Movimientos”: sus orígenes y evolución, las asociaciones y redes sociales que lo integran, su estructuración interna, sus críticas a la globalización neoliberal y sus demandas, sus propuestas alternativas y, en fin, sus formas de acción. Las contribuciones siguientes examinan aspectos más sectoriales del activismo alterglobalizador El Movimiento Alterglobalizador es sumamente heterogéneo en todos sus aspectos –sociales, culturales, étnicos, políticos y organizativos-, y en modo alguno puede considerársele un movimiento exclusivamente juvenil. Sin embargo, la presencia y el protagonismo de los colectivos juveniles son en Jóvenes, globalizaciónaltermundistas y movimientos él muy considerables. -

Vínculos Entre Los Zapatistas Y Los Magonistas Durante La Revolución Mexicana

Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana ISSN: 1315-5216 ISSN: 2477-9555 [email protected] Universidad del Zulia Venezuela Vínculos entre los zapatistas y los magonistas durante la Revolución Mexicana TREJO MUÑOZ, Rubén Vínculos entre los zapatistas y los magonistas durante la Revolución Mexicana Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana, vol. 25, núm. 90, 2020 Universidad del Zulia, Venezuela Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=27965038006 PDF generado a partir de XML-JATS4R por Redalyc Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Rubén TREJO MUÑOZ. Vínculos entre los zapatistas y los magonistas durante la Revolución Mexicana ARTÍCULOS Vínculos entre los zapatistas y los magonistas durante la Revolución Mexicana Rubén TREJO MUÑOZ Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México, México id=27965038006 [email protected] Recepción: 02 Febrero 2020 Aprobación: 30 Abril 2020 Resumen: Recuperar la memoria histórica de las dos tendencias radicales y anticapitalistas de la Revolución Mexicana desarrollada entre 1910 y 1920. El presente texto forma parte de una investigación en curso sobre los vínculos entre el zapatismo y el magonismo durante la Revolución Mexicana. Exponemos únicamente dos episodios que muestran esa colaboración. El primero refiere la participación de Ángel Barrios, magonista y zapatista destacado, en la lucha tanto del PLM como del Ejército Libertador del Sur. El segundo, es la narración de la visita que hace el magonista José Guerra a Emiliano Zapata en 1913. Palabras clave: Magonismo, zapatismo, Revolucion Mexicana, Tierra y Libertad. Abstract: Recovering the historical memory of the two radical and anticapitalistic tendencies in the 1910-1920 Mexican Revolution. -

Gramática Popular Del Mixteco Del Municipio De Tezoatlán, San Andrés Yutatío, Oaxaca

SERIE gramáticas de lenguas indígenas de México 9 Gramática popular del mixteco del municipio de Tezoatlán, San Andrés Yutatío, Oaxaca Judith Ferguson de Williams Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, A.C. Gramática popular del mixteco del municipio de Tezoatlán, San Andrés Yutatío, Oaxaca San Andrés Yutatío Serie de gramáticas de lenguas indígenas de México Núm. 9 Serie dirigida por J. Albert Bickford Equipo de redacción y corrección Susan Graham Elena Erickson de Hollenbach Sharon Stark Equipo de corrección del español Sylvia Jean Ossen M. De Riggs Érika Becerra Bautista Miriam Pérez Luría Lupino Ultreras Ortiz Adriana Ultreras Ortiz El diseño de la pasta es la Estela 12 de Monte Albán I de influencia olmeca (dibujo por Catalina Voigtlander) Gramática popular del mixteco del municipio de Tezoatlán, San Andrés Yutatío, Oaxaca (versión electrónica) Judith Ferguson de Williams publicado por el Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, A.C. Apartado Postal 22067 14000 Tlalpan, D.F., México Tel. 555-573-2024 www.sil.org/mexico 2007 Las fotografías del pueblo de San Andrés Yutatío fueron tomadas por Juan Williams H. Los mapas fueron elaborados por Susan Graham. Las piezas arqueológicas de las ilustraciones se encuentran en el Museo Nacional de Antropología y en el Museo Regional de Oaxaca. Algunas de las fotografías arqueológicas fueron tomadas por Ruth María Alexander, la cual se indica en las páginas respectivas. Las demás fueron tomadas por Alvin y Louise Schoenhals. Los dibujos de las piezas arqueológicas fueron elaborados por Catalina Voigtlander. – ·· – Para más información acerca del mixteco de San Andrés Yutatío y el municipio de Tezoatlán, véase www.sil.org/mexico/mixteca/tezoatlan/00e-MixtecoTezoatlan-mxb.htm © 2007 Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, A.C. -

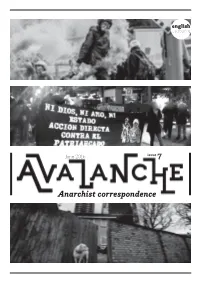

Avalanche EN 7.Indd

english VERSION June 2016 issue 7 Anarchist correspondence Uruguay The Netherlands Anarquía Roofdruk periodicoanarquia.wordpress.com [email protected] Chile Germany Contra toda autoridad Attacke! (Norden) contratodaautoridad.wordpress.com [email protected] El Sol Ácrata (Antofagasta) Fernweh (München) periodicoelsolacrata.wordpress.com fernweh.noblogs.org Sin Banderas Ni Fronteras (Santiago) Chronik [email protected] chronik.blackblogs.org Argentine Switzerland Exquisita Rebeldía (Buenos Aires) Dissonanz (Zürich) [email protected] [email protected] Abrazando el Caos [email protected] Sweden Rebelion (Buenos Aires) Upprorsbladet (Stockholm) [email protected] [email protected] Mexico UK Negación Rabble (London) [email protected] rabble.org.uk Italy Canada Finimondo Wreck (Vancouver) finimondo.org wreckpublication.wordpress.com Tairsìa (Salento) Montréal Contre-Information [email protected] mtlcounter-info.org Stramonio (Milano) USA [email protected] Rififi (Bloomington) Brecce (Lecce) rififibloomington.wordpress.com [email protected] Trebitch Times (St Louis) Spain trebitchtimes.noblogs.org Infierno PugetSoundAnarchists (Pacific Northwest) [email protected] pugetsoundanarchists.org Wildfire France wildfire.noblogs.org Lucioles (Paris) luciolesdanslanuit.blogspot.fr + Séditions (Besançon) Contrainfo seditions.noblogs.org contrainfo.espiv.net Paris Sous Tension (Paris et au-delà) Tabula Rasa parissoustension.noblogs.org atabularasa.org -

Legacies of the Mexican Revolution” a Video Interview with Professor Aurora Gómez-Galvarriato

DISCUSSION GUIDE FOR “LEGACIES OF THE MEXICAN REVOLUTION” a video interview with Professor Aurora Gómez-Galvarriato Organizing • What were the immediate and long-term legacies of the Mexican Questions Revolution within Mexico? • What legacies of the Mexican Revolution were intended from its outset? Which were achieved and which were not achieved? Summary Aurora Gómez-Galvarriato is a Professor of Historical Studies at Colegio de México. In this 18-minute video, Professor Gómez-Galvarriato discusses how perceptions of the legacies of the Mexican Revolution have changed over time. She talks about the immediate legacies of the Revolution, intended outcomes that did not materialize, and the legacies that have persisted until today. Objectives During and after viewing this video, students will: • identify the immediate and long-term consequences of the Mexican Revolution; • discuss to what extent the goals of the original revolutionaries were achieved by the end of the Mexican Revolution; and • evaluate whether the benefits of the Mexican Revolution justified the costs. Materials Handout 1, Overview of the Mexican Revolution, pp. 5–10, 30 copies Handout 2, Video Notes, pp. 11–13, 30 copies “LEGACIES OF THE MEXICAN REVOLUTION” DISCUSSION GUIDE 1 introduction Handout 3, Perspectives on the Legacies of the Mexican Revolution, p. 14, 30 copies Handout 4, Synthesis of Perspectives, pp. 15–16, 30 copies Handout 5, Assessing the Mexican Revolution’s Costs and Benefits, p. 17, 30 copies Answer Key 1, Overview of the Mexican Revolution, pp. 18–19 Answer Key 2, Video Notes, pp. 20–21 Answer Key 3, Perspectives on the Legacies of the Mexican Revolution, p. -

Drew Halevy on Emiliano Zapata: Revolution and Betrayal in Mexico

Samuel Brunk. Emiliano Zapata: Revolution and Betrayal in Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995. xvi + 360 pp. $45.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-8263-1619-6. Reviewed by Drew P. Halevy Published on H-LatAm (April, 1996) Emiliano Zapata: Revolution and Betrayal in nity. Zapata, as presented by Brunk, is a man Mexico by Samuel Brunk gives a highly redefined whose worldview and political beliefs and devel‐ view of Zapata and his revolutionary movement. opment as a leader evolved slowly over time. Brunk approaches Zapata from a different per‐ Brunk gives a fairly concise overview of the spective than seen in previous works, looking at roots of the Mexican Revolution in the beginning Zapata the man, rather than Zapata the leader. of the work. The last two-thirds of the book deal In his introduction, Brunk states that the "pri‐ with Zapata's increasing role in the Mexican Revo‐ mary goal of this book, then, is to provide a much lution. needed political biography of Zapata, and to Zapata is presented objectively by Brunk in demonstrate in the process that his choices and this work. Brunk does not shy away from dealing actions did have a historical impact" (p. xvi). By with the historical charges of brutality and ban‐ taking this approach, Brunk not only gives a back‐ ditry made against some of those under Zapata's ground to Zapata's political belief, but also greatly banner. While acknowledging these actions, humanizes Zapata the historical figure. Brunk tends to downplay them, stating that other Brunk starts his work by examining Zapata's revolutionary groups were also guilty of atroci‐ upbringing in the state of Morelos. -

Soldaderas and the Staging of the Mexican Revolution 1

Soldaderas and the Staging of the Mexican Revolution 1 Alicia Arrizón Si Adelita se fuera con otro la seguiría por tierra y por mar. Si por mar en un buque de guerra Si por tierra en un tren militar. Adelita, por Dios te lo ruego, calma el fuego de esta mi pasión, porque te amo y te quiero rendido y por ti sufre mi fiel corazón. 2 If Adelita should go with another I would follow her over land and sea. If by sea in a battleship If by land on a military train. Adelita, for God’s sake I beg you, calm the fire of my passion, because I love you and I cannot resist it and my faithful heart suffers for you. 3 “La Adelita” was one of the most popular songs of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920). According to some sources (see Soto 1990:44), this ballad was originally inspired by a Durangan woman who had joined the Maderista movement4 at an early age. Troubadours made the song—and Adelita her- self—a popular emblem of the Revolution. As Baltasar Dromundo put it, “las guitarras de todas partes se iban haciendo eruditas en ese canto hasta que por fin la Revolución hizo de ella su verdadero emblema nacional” (guitar ists from all over were becoming experts in that song and it became the true em- blem of the Revolution) ( 1936:40). Significantly, Adelita’s surname, as well as the family names of many other soldaderas (soldier-women), remained virtually unknown. However, the popular songs composed in honor of these women contributed enormously to their fame and to documenting their role in the Revolution. -

Redalyc.MUJERES INDÍGENAS EN EL SISTEMA DE

Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo ISSN: 1870-5472 [email protected] Colegio de Postgraduados México Barrera-Bassols, Dalia MUJERES INDÍGENAS EN EL SISTEMA DE REPRESENTACIÓN DE CARGOS DE ELECCIÓN. EL CASO DE OAXACA Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo, vol. 3, núm. 1, enero-junio, 2006, pp. 19-37 Colegio de Postgraduados Texcoco, Estado de México, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=360533075002 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto MUJERES INDÍGENAS EN EL SISTEMA DE REPRESENTACIÓN DE CARGOS DE ELECCIÓN. EL CASO DE OAXACA INDIGENOUS WOMEN IN THE REPRESENTATION SYSTEM FOR ELECTIVE POSTS. THE CASE OF OAXACA Dalia Barrera-Bassols División de Posgrado de la Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia. ([email protected]) RESUMEN ABSTRACT En este trabajo se discute el acceso de las mujeres indígenas a los In this paper the indigenous women access to posts in the municipal cargos en ayuntamientos de los municipios del estado de Oaxaca, councils of the state municipalities of Oaxaca is discussed. The que tiene 23% de los 2440 municipios del país. Se examina la state has 23% of the 2440 municipalities of the country. The posibilidad de nombramiento de las autoridades municipales por possibility of nominating municipal authorities by two ways is dos vías: el nombramiento en asamblea por el sistema de usos y examined: the nomination in the assembly by the indigenous uses costumbres indígenas y la elección local por votación, como re- and customs system and by voting in a local election, as a result sultado de la competencia entre partidos políticos. -

A Comparative Analysis of Political Ideology Convergencia

Convergencia. Revista de Ciencias Sociales ISSN: 1405-1435 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México México Flores, María de los Ángeles Film vs. Television Versions of the Mexican Revolution: a Comparative Analysis of Political Ideology Convergencia. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, vol. 7, núm. 23, septiembre, 2000, pp. 177-195 Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México Toluca, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=10502307 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Film Vs. Tele vi sion Ver sions of the Mex i can Rev o lu tion: a Com par a tive Anal y sis of Po lit i cal Ide ol ogy1 María de los Ángeles Flores Gutiérrez Universidad de Texas en Aus tin, USA Resumen: El objetivo de este artículo es presentar un análisis comparativo en tre la manera que la televisión y el cine representan la ideología política de la Revolución Mexicana. Fran cisco I. Madero y Ricardo Flores Magón son considerados los más importantes precursores ideológicos de la lucha ar mada. En este estudio presentamos sus principales líneas de pensamiento, igualmente se analiza la forma en que el cine y la televisión han representado en pantalla sus ideas revolucionarias. La muestra de este estudio es la película de la época de oro del cine mexicano “Enamorada” (1946) y la telenovela “Senda de Glo ria” (1987). -

Plan of Ayala, 1911, by Emiliano Zapata

http://social.chass.ncsu.edu/slatta/hi216/documents/ayala.htm Plan of Ayala, 1911, by Emiliano Zapata Note on the document: Zapata and his peasant followers in Morelos fought hard against the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz, trying to regain their lands stolen from them. Originally a backer and ally of Diaz's successor, President Francisco Madero, Zapata turned against Madero after concluding that the new president had betrayed his promises to the people of Mexico. Look for specific complaints lodged by Zapata and his followers against Madero. Thanks to Professor Richard Slatta for permission to reproduce this translation and introduction from his web site. Liberating Plan of the sons of the State of Morelos, affiliated with the Insurgent Army which defends the fulfillment of the Plan of San Luis, with the reforms which it has believed proper to add in benefit of the Mexican Fatherland. We who undersign, constituted in a revolutionary junta to sustain and carry out the promises which the revolution of November 20, 1910 just past, made to the country, declare solemnly before the face of the civilized world which judges us and before the nation to which we belong and which we call [sic, llamamos, misprint for amamos, love], propositions which we have formulated to end the tyranny which oppresses us and redeem the fatherland from the dictatorships which are imposed on us, which [propositions] are determined in the following plan: 1. Taking into consideration that the Mexican people led by Don Francisco I. Madero went to shed their blood to reconquer liberties and recover their rights which had been trampled on, and not for a man to take possession of power, violating the sacred principles which he took an oath to defend under the slogan "Effective Suffrage and No Reelection," outraging thus the faith, the cause, the justice, and the liberties of the people: taking into consideration that that man to whom we refer is Don Francisco I. -

The Economy of Oaxaca Decomposed

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2015 The conomE y of Oaxaca Decomposed Albert Codina Sala Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Growth and Development Commons, Income Distribution Commons, International Economics Commons, Macroeconomics Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Recommended Citation Codina Sala, Albert, "The cE onomy of Oaxaca Decomposed" (2015). University Honors Program Theses. 89. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/89 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Economy of Oaxaca Decomposed An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in Department of Finance and Economics. By Albert Codina Sala Under the mentorship of Dr. Gregory Brock ABSTRACT We analyze the internal economy of Oaxaca State in southern Mexico across regions, districts and municipalities from 1999 to 2009. Using the concept of economic convergence, we find mixed evidence for poorer areas catching up with richer areas during a single decade of economic growth. Indeed, some poorer regions thanks to negative growth have actually diverged away from wealthier areas. Keywords: Oaxaca, Mexico, Beta Convergence, Sigma Convergence Thesis Mentor: _____________________ Dr. Gregory Brock Honors Director: _____________________ Dr. Steven Engel April 2015 College of Business Administration University Honors Program Georgia Southern University Acknowledgements The first person I would like to thank is my research mentor Dr.