St. Vigeans Stones (And Museum)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crawford Park, Northmuir, Kirriemuir Angus DD8 4PJ Bellingram.Co.Uk Lot 1 Lot 1

Crawford Park, Northmuir, Kirriemuir Angus DD8 4PJ bellingram.co.uk Lot 1 Lot 1 Lot 1 Lot 1 2 Rural property requiring renovation and modernisation with equestrian or small holding potential and three holiday cottages nearby offering an additional income stream. Available as a Whole or in Lots Lot 1: Crawford Park, Mid Road, Northmuir, Kirriemuir DD8 4PJ Lot 2: Clova Cottage, Foreside of Cairn, Forfar DD8 3TQ Lot 3: Esk Cottage, Foreside of Cairn, Forfar DD8 3TQ Lot 4: Prosen Cottage, Foreside of Cairn, Forfar DD8 3TQ Lot 2-4 Bell Ingram Forfar Manor Street, Forfar, Angus, DD8 1EX [email protected] 01307 462 516 Viewing Description Strictly by appointment with Bell Ingram Forfar office – 01307 462516. Crawford Park is an attractive three or four bedroom detached stone property with scope for modernisation and renovation. The property has a range of outbuildings, including a stable block along with two paddocks and an outdoor ménage. The gorunds extend to about Lot 1: Crawford Park, Mid Road, Northmuir, Kirriemuir DD8 4PJ 2.38 hectares (5.88 acres). Directions Crawford Park House From Forfar take the A926 road to Kirriemuir, passing over the A90 and continuing through The property is a trad itional one and a half storey, of stone construction with a slate roof and is Padanaram and Maryton. Continue on the A926 and turn left onto Morrison Street (opposite double glazed throughout. The property does require a degree of renovation and modernisation Thrums the vets). At the crossroads continue straight over onto Lindsay Street. Continue on and offers the Purchaser the opportunity to put their own stamp on the house. -

Tayside, Angus and Perthshire Fibromyalgia Support Group Scotland

Tayside, Angus and Perthshire Angus Long Term Conditions Support Fibromyalgia Support Group Scotland Groups Offer help and support to people suffering from fibromyalgia. This help and support also extends to Have 4 groups of friendly people who meet monthly at family and friends of sufferers and people who various locations within Angus and offer support to people would like more information on fibromyalgia. who suffer from any form of Long Term Condition or for ANGUS Directory They meet every first Saturday of every month at carers of someone with a Long Term Condition as well as Ninewells Hospital, Dundee. These meetings are each other, light refreshments are provided. to Local held on Level 7, Promenade Area starting at 11am For more information visit www.altcsg.org.uk or e-mail: Self Help Groups and finish at 1pm. [email protected] For more information contact TAP FM Support Group, PO Box 10183, Dundee DD4 8WT, visit www.tapfm.co.uk or e-mail - [email protected] . Multiple Sclerosis Society Angus Branch For information about, or assistance about the Angus Gatepost Branch please call 0845 900 57 60 between 9am - 8pm or e-mail Brian Robson at mailto:[email protected] GATEPOST is run by Scottish farming charity RSABI and offers a helpline service to anyone who works on the land in Scotland, and also their families. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic They offer a friendly, listening ear and a sounding post for Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) you at difficult times, whatever the reason. If you’re The aims of the support group are to give support to worried, stressed, or feeling isolated, they can help. -

1831 - 32 Dundee Sassines Starting by L

Friends of Dundee Surnames City Archives 1831 - 32 Dundee Sassines starting by L Surname PreNamesDate Occupation Parish Date Seised Main Subject Information Sassine No Law Robert02/05/1831 Weaver, Aberdeen Brechin 22/04/1831 Cockburn's Croft 141 Leader John Temple31/01/1832 Montrose 26/01/1832 235 square yards of the of Putney Co. Surrey 482 common lands of the Burgh of Montose Leader John Temple25/01/1832 Montrose 24/01/1832 Links of Montrose of Putney, Co. Surrey 479 Leader John Temple06/02/1832 Arbroath 02/02/1832 Abbey of Arbroath of Putney Co. Surrey 487 Lindsay Mary, Trustees of10/01/1831 Dundee 10/01/1831 Hillton of Dundee Mary Lindsay relict of of David 5 Morris, Blacksmith Dundee. Laigh Shade or Forebank Lindsay John Mackenzie16/01/1832 Montrose 31/12/1831 Langley Park 470 W.S. Livingstone Willaim30/06/1831 Merchant, St Vigeans 28/06/1831 Dishlandtown 234 Carnoustie Livingstone William24/05/1831 Merchant, Barrie 23/05/1831 Graystane Ward 163 Carnoustie Louson David27/09/1831 Town Clerk of St Vigeans 23/09/1831 Ponderlawfield 358 Arbroath Louson David27/09/1831 Town Clerk of St Vigeans 24/09/1831 Springfield 357 Arbroath 27 June 2011 IDMc ‐ June 2011 Page 1 of 3 Surname PreNamesDate Occupation Parish Date Seised Main Subject Information Sassine No Love Arthur24/06/1831 Merchant, Arbroath Arbroath 17/06/1831 Abbey of Arbroath West side of eastmost street of the 216 Abbey Low Thomas03/11/1831 Gardener, Duntrune Dundee 19/10/1831 Marytown part of Estate of Craigie 396 Low Andrew19/03/1831 Shipowner Dundee 19/03/1831 Dundee part of Kirkroods 99 Lowden John13/01/1831 Weaver Dundee 12/01/1831 Hawkhill near Dundee This was along with his wife Isobel 11 Farmer Lowden William01/02/1831 Manufacturer Dundee 01/02/1831 Hilltown of Dundee 41 Lowe Robert15/10/1831 Teacher of Dancing, Brechin 05/09/1831 Over Tenements of Caldhame Presently in Brechin. -

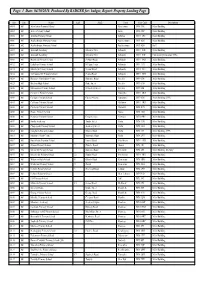

1281/06 Angus Council

Agenda Item No 3 REPORT NO. 1281/06 ANGUS COUNCIL CIVIC LICENSING COMMITTEE – 24 OCTOBER 2006 DELEGATED APPROVALS REPORT BY THE DIRECTOR OF CORPORATE SERVICES ABSTRACT The purpose of this Report is to advise members of applications for licences under the Civic Government (Scotland) Act 1982 and other miscellaneous Acts which have been granted/renewed by the Head of Law and Administration in accordance with the Scheme of Delegation appended to Standing Orders. 1. RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that the Committee note the licences granted/renewed under delegated authority as detailed in the attached Appendix. 2. BACKGROUND In terms of the Scheme of Delegation to Officers, the Head of Law and Administration is authorised to grant certain applications in connection with the Council's licensing functions under the Civic Government (Scotland) Act 1982 and other miscellaneous Acts. Attached as an Appendix is a list of applications granted/renewed under delegated authority during the period 21 August 2006 to 9 October 2006. 3. FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS There are no financial implications arising from this Report. 4. HUMAN RIGHTS IMPLICATIONS There are no Human Rights issues arising directly from this Report. COLIN MCMAHON DIRECTOR OF CORPORATE SERVICES SCH/KB NOTE: No background papers as defined by Section 50D of the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 (other than any containing confidential or exempt information) were relied on to any material extent in preparing this Report. APPENDIX 1 LICENCES GRANTED/RENEWED UNDER DELEGATED AUTHORITY From -

Forfar G Letham G Arbroath

Timetable valid from 30th March 2015. Up to date timetables are available from our website, if you have found this through a search engine please visit stagecoachbus.com to ensure it is the correct version. Forfar G Letham G Arbroath (showing connections from Kirriemuir) 27 MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS route number 27 27C 27A 27 27 27 27 27 27 27A 27B 27 27 27 27 27 27 27 G Col Col NCol NSch Sch MTh Fri Kirriemuir Bank Street 0622 — 0740 0740 0835 0946 1246 1346 1446 — — — — 1825 1900 2115 2225 2225 Padanaram opp St Ninians Road 0629 — 0747 0747 0843 0953 1253 1353 1453 — — — — 1832 1907 2122 2232 2232 Orchardbank opp council offi ces — — 0752 0752 | | | | | — — — — | | | | | Forfar Academy — — | | | M M M M — 1555 — — | | | | | Forfar East High Street arr — — | | | 1003 1303 1403 1503 — | — — | | | | | Forfar New Road opp Asda — — M M M 1001 1301 1401 1501 1546 | 1646 — M M M M M Forfar East High Street arr 0638 — 0757 0757 0857 1002 1302 1402 1502 1547 | 1647 — 1841 1916 2131 2241 2241 Forfar East High Street dep 0647 0800 0805 0805 0905 1005 1305 1405 1505 1550 | 1655 1745 1845 1945 2155 2255 2255 Forfar Arbroath Rd opp Nursery 0649 0802 | 0807 0907 1007 1307 1407 1507 | | 1657 1747 1847 1947 2157 2257 2257 Forfar Restenneth Drive 0650 | M 0808 0908 1008 1308 1408 1508 M M 1658 1748 1848 1948 2158 2258 2258 Kingsmuir old school 0653 | 0809 0811 0911 1011 1311 1411 1511 1554 1604 1701 1751 1851 1951 2201 2301 2301 Dunnichen M | M M M M M M M M 1607 M M M M M M M Craichie village 0658 | 0814 0816 0916 1016 1316 1416 1516 1559 | 1706 1756 1856 1956 -

Property Landing Page

Page: 1 Date: 04/10/2018 Produced By BADGER for: badger, Report: Property Landing Page Site Unit Name Add1 Add2 Town Post Code Description 0001 001 Aberlemno Primary School Aberlemno DD8 3PE Main Building 0002 001 Airlie Primary School Airlie DD8 5NP Main Building 0004 001 Arbirlot Primary School Arbirlot DD11 2PZ Main Building 0006 001 Auchterhouse Primary School Auchterhouse DD3 0QS Main Building 0006 002 Auchterhouse Primary School Auchterhouse DD3 0QS Hall 0007 001 Arbroath Academy Glenisla Drive Arbroath DD11 5JD Main Building 0007 041 Arbroath Academy Glenisla Drive Arbroath DD11 5JD Community Education Office 0008 001 Hayshead Primary School St Abbs Road Arbroath DD11 5AB Main Building 0012 001 Ladyloan Primary School Millgate Loan Arbroath DD1 1LX Main Building 0013 001 Muirfield Primary School 5 School Road Arbroath DD11 2LU Main Building 0014 001 St Thomas RC Primary School Seaton Road Arbroath DD11 5DT Main Building 0024 001 Damacre Community Centre Damacre Road Brechin DD9 6DU Main Building 0025 001 Brechin High School Duke Street Brechin DD9 6LB Main Building 0026 001 Maisondieu Primary School St Andrew Street Brechin DD9 6JB Main Building 0028 001 Carmyllie Primary School Carmyllie DD11 2RD Main Building 0040 001 Carlogie Primary School Caeser Avenue Carnoustie DD7 6DS Main Building (PPP) 0043 001 Colliston Primary School Colliston DD11 3RR Main Building 0044 001 Cortachy Primary School Cortachy DD8 4LX Main Building 0050 001 Eassie Primary School Eassie DD8 1SQ Main Building 0056 001 Ferryden Primary School Craig Terrace -

Angus, Scotland Fiche and Film

Angus Catalogue of Fiche and Film 1841 Census Index 1891 Census Index Parish Registers 1851 Census Directories Probate Records 1861 Census Maps Sasine Records 1861 Census Indexes Monumental Inscriptions Taxes 1881 Census Transcript & Index Non-Conformist Records Wills 1841 CENSUS INDEXES Index to the County of Angus including the Burgh of Dundee Fiche ANS 1C-4C 1851 CENSUS Angus Parishes in the 1851 Census held in the AIGS Library Note that these items are microfilm of the original Census records and are filed in the Film cabinets under their County Abbreviation and Film Number. Please note: (999) number in brackets denotes Parish Number Parish of Auchterhouse (273) East Scotson Greenford Balbuchly Mid-Lioch East Lioch West Lioch Upper Templeton Lower Templeton Kirkton BonninGton Film 1851 Census ANS 1 Whitefauld East Mains Burnhead Gateside Newton West Mains Eastfields East Adamston Bronley Parish of Barry (274) Film 1851 Census ANS1 Parish of Brechin (275) Little Brechin Trinity Film 1851 Census ANS 1 Royal Burgh of Brechin Brechin Lock-Up House for the City of Brechin Brechin Jail Parish of Carmyllie (276) CarneGie Stichen Mosside Faulds Graystone Goat Film 1851 Census ANS 1 Dislyawn Milton Redford Milton of Conan Dunning Parish of Montrose (312) Film 1851 Census ANS 2 1861 CENSUS Angus Parishes in the 1861 Census held in the AIGS Library Note that these items are microfilm of the original Census records and are filed in the Film cabinets under their County Abbreviation and Film Number. Please note: (999) number in brackets denotes Parish Number Parish of Aberlemno (269) Film ANS 269-273 Parish of Airlie (270) Film ANS 269-273 Parish of Arbirlot (271) Film ANS 269-273 Updated 18 August 2018 Page 1 of 12 Angus Catalogue of Fiche and Film 1861 CENSUS Continued Parish of Abroath (272) Parliamentary Burgh of Abroath Abroath Quoad Sacra Parish of Alley - Arbroath St. -

Angus Long Term Conditions Support Group (ALTCSG)

Angus Self Management Long Term Conditions Angus Self-management gives you the skills to manage your Support Groups condition. It is crucial for your emotional and physical well-being. Arbroath Group Long Managing your condition is hugely liberating. As well Last Monday of the Month in the Boardroom, Arbroath as benefiting your physical and mental health, it can Infirmary, Arbroath, 2 until 4pm4pm. Montrose Group help in all aspects of life: aiding relationships, Meetings Proposed for Last Tuesday of the Month Contact Term reducing workplace stresses, or helping you get us for more information. Carnoustie Group back into work, reducing social isolation, to name Last Wednesday of the Month in the Parkview Primary Care but a few. Centre, Barry Road, Carnoustie, 2 until 4pm4pm. Brechin Group Conditions Learning about your condition is the first step in Last Thursday of the Month in Brechin Infirmary, Infirmary Road, Brechin, (Meet in MIU waiting area where ALTCSG self-management – in particular, how your member will greet you, PLEASE DO NOT PRESS MIU BELL for attention), 2 until 4pm4pm. condition affects you. This can help you to Forfar Group Support predict when you might experience symptoms, Last Friday of the Month in Academy Medical Centre, and to think through how to work around them. Academy Street, Forfar. 4 until 6pm Through attending self management courses called “Challenging Your Condition” you will Groups be better able to understand your condition and learn a range of techniques to use to help you cope with day to day life. -

Bathing Water Profile for Arbroath (West Links)

Bathing Water Profile for Arbroath (West Links) Arbroath, Scotland _____________ Current water classification https://www2.sepa.org.uk/BathingWaters/Classifications.aspx _____________ Description The Arbroath (West Links) bathing water is a 1.3 km sandy bay situated to the south west of the town of Arbroath in Angus. The beach is popular due to the provision of a coastal footpath and close proximity of a recreational area. During high and low tides the approximate distance to the water’s edge can vary from 20–200 metres. The sandy beach slopes gently towards the water. For local tide information see: http://easytide.ukho.gov.uk/EasyTide/index.aspx Site details Local authority Angus Council Year of designation 1987 Water sampling location NO 6351 3998 Bathing water ID UKS761603 Catchment description The catchment draining into Arbroath (West Links) bathing water extends to 44 km2. It varies in topography from low-lying areas along the coast to low hills in the west. The catchment is predominantly rural (96%) with arable agriculture the major land use. There is also some beef and sheep farming in the area. Approximately 4% of the bathing water catchment is urban; the main urban area being the town of Arbroath. There are also a number of other small settlements within the catchment. The main rivers within the bathing water catchment are the Elliot Water, the Geordies Burn and Brothock Water. The Elliot Links Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), designated for its sand dunes, is located within the bathing water catchment. The Strathmore/Fife area was designated as a Nitrate Vulnerable Zone in 2002. -

Aberdeen City Council Aberdeenshire Council Angus Council

1932 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE FRIDAY 10 SEPTEMBER 1999 Proposals Requiring Listed Building/Conservation Area Consent SOUTH DIVISION Period for lodging representations - 21 days Address representations to: George W Chree, Head of Planning Applebank House Sub-division of house Mr & Mrs 98/2030 Services (South), Aberdeenshire Council, Viewmount, Arduthie 24 The Spital into two houses, Birchley Road, Stonehaven AB39 2DQ Aberdeen erection of a conserv- (Conservation atory and alterations Address of Proposal/ Name and Where plans can Area 1) to front boundary wall Proposal Reference Address of be Inspected in Applicant addition to Div- 347 Union Street Installation of new Yu Chinese 99/1491 isional Office Aberdeen shop front to rear of Restaurant Development Affecting the Character of a Listed Building (Category C(S) existing Hot Food Period for Lodging Representations - 21 days Listed Building Licensed premises Durris Retention of Durris Parish Banchory within Conser- to form takeaway Parish Church existing temporary Church Area Office vation Area 2) Kirkton building for use as c/o Ron The Square of Durris church Sunday Gauld Banchory 86'/2 Crown Street Erection of hanging McKenzie& 99/1500 school (for a Architects Aberdeen ,' sign, signboard and Morrison period of 5 years) 660 Holburn Street (Category B Listed brass plaque Dental Practice S990837PF Aberdeen (1601/9) Building within Conservation Area 3) 44 Union Street Installation of shop The Outdoor 99/1501 Angus Council Aberdeen front and internal Group Limited (Category B Listed alterations to existing TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (SCOTLAND) ACT Building within staircase at first floor level 1997 AND RELATED LEGISLATION Conservation Area 2) The following applications have been submitted to Angus Council. -

Kinnettles Kist

Kinnettles Kist Published by Kinnettles Heritage Group Printed by Angus Council Print & Design Unit. Tel: 01307 473551 © Kinnettles Heritage Group. First published March 2000. Reprint 2006. Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 - A Brief Geography Lesson 2 Chapter 2 - The Kerbet and its Valley 4 Chapter 3 - The Kirk and its Ministers 17 Chapter 4 - Mansion Houses and Estates 23 Chapter 5 - Interesting Characters in Kinnettles History 30 Chapter 6 - Rural Reminiscences 36 Chapter 7 - Kinnettles Schools 49 Chapter 8 - Kinnettles Crack 62 Chapter 9 - Farming, Frolics and Fun 74 Chapter 10 - The 1999 survey 86 Acknowledgements 99 Bibliography 101 Colour Plates : People and Places around Kinnettles i - xii Introduction Kinnettles features in all three Statistical Accounts since 1793. These accounts were written by the ministers of the time and, together with snippets from other books such as Alex Warden’s “Angus or Forfarshire – The Land and People”, form the core of our knowledge of the Parish’s past. In the last 50 years the Parish and its people have undergone many rapid and significant changes. These have come about through local government reorganisations, easier forms of personal transport and the advent of electricity, but above all, by the massive changes in farming. Dwellings, which were once farmhouses or cottages for farm-workers, have been sold and extensively altered. New houses have been built and manses, and even mansion houses, have been converted to new uses. What used to be a predominantly agricultural community has now changed forever. The last full Statistical Account was published in 1951, with revisions in 1967. -

Brechin Castle Brechin Castle Stands Proud on a Massive Bluff of Rocks Above the Banks of the River South Esk

BRECHIN CASTLE ANGUS On the instruction of The Earl and Countess of Dalhousie BRECHIN CASTLE ANGUS Dundee 26 miles ~ Aberdeen 42 miles ~ Edinburgh 86 miles (Distances are approximate) One of Scotland’s most significant and historic castles Brechin Castle (8 reception rooms, 16 bedrooms and 10 bathrooms) Renowned Walled Garden Estate courtyard with exciting conversion possibilities 5 estate cottages About 40 acres of magniicent policies Fishing on River South Esk about 70 acres in total For sale as a whole Savills Edinburgh Savills London Savills Brechin Wemyss House 33 Margaret Street 12 Clerk Street 8 Wemyss Place London Brechin Edinburgh EH3 6DH W1G 0JD Angus DD6 9AE [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 131 247 3720 +44 (0) 20 7016 3780 +44 (0) 1356 628 628 These particulars are only a guide and must not be relied on as a statement of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of text. 1 Situation Located on the east coast of Scotland, Angus Cross (scheduled journey time 6 hours and is a county renowned for its heather clad 17 minutes) in addition to a hugely convenient hills, productive farmland, historic castles sleeper service. Three airports can be reached: and attractive coastline. The county of Angus Dundee Airport (31 miles) is the closest and is perhaps lesser known than its neighbour offers daily lights to London Stansted as well Perthshire, but is equally beautiful, for its as accommodating private jet aircraft. Aberdeen varied coastline from Dundee, home to The (42 miles) and Edinburgh (84 miles) airports Discovery and recently opened V&A museum both offer domestic lights to London and many to the Montrose Basin, an incredibly important of the UK’s major cities as well as European sanctuary for thousands of waders, wildfowl lights and connections to many international and migratory pink footed geese each year.