The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia Second Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shwe U Daung and the Burmese Sherlock Holmes: to Be a Modern Burmese Citizen Living in a Nation‐State, 1889 – 1962

Shwe U Daung and the Burmese Sherlock Holmes: To be a modern Burmese citizen living in a nation‐state, 1889 – 1962 Yuri Takahashi Southeast Asian Studies School of Languages and Cultures Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney April 2017 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Statement of originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Yuri Takahashi 2 April 2017 CONTENTS page Acknowledgements i Notes vi Abstract vii Figures ix Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Biography Writing as History and Shwe U Daung 20 Chapter 2 A Family after the Fall of Mandalay: Shwe U Daung’s Childhood and School Life 44 Chapter 3 Education, Occupation and Marriage 67 Chapter ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1917 and 1930 88 Chapter 5 ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1930 and 1945 114 Chapter 6 ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1945 and 1962 140 Conclusion 166 Appendix 1 A biography of Shwe U Daung 172 Appendix 2 Translation of Pyone Cho’s Buddhist songs 175 Bibliography 193 i ACKNOWLEGEMENTS I came across Shwe U Daung’s name quite a long time ago in a class on the history of Burmese literature at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. -

Vesak Eng.Pdf

Vasak Day and Global Civilization Author : Phra Brahmagunabhorn (P.A.Payutto) Translator : Ven.Asst.Prof. Dr. Phramaha Hansa Dhammahaso Edited : Mr. Robin Philip Moor Graphic Design : Sarun Upansak, Usa Bunjonjad First Printing : 3000 Copies, May 2011 Published by : Mahachulalongkorn rajavidyalaya University 79 M.1, Lam Sai, Wang Noi, Ayutthaya, 13170, Thailand. Tel. +66 (035)24-8000 www.mcu.ac.th Printed by : Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya Press Wat Mahathatu. Tha Prachan, Phra Nakhon, Bangkok 10200 Tel 0-2221-8892 Fax 0-2923-5623 www.mcu.ac.th Preface Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University (MCU) has been privileged to witness and play a crucial role in developing and hosting successful UNDV celebrations from the beginning in 2004/ 2547 to 2011/2554 (except in 2008/2551 – the celebrations were held in Hanoi, Vietnam). As always, we are all very grateful to the Royal Thai Government for its constant support, and thank the Thai Supreme Sangha Council for its blessings, guidance and support. We are indebted, also, to the United Nations for recognizing the thrice-sacred Buddhist holy day. It has been 2554 years since the death of our Great Teacher, and we have gathered here from across the globe, from many nations, to again pay tribute to his birth, enlightenment, and death – occurring on the same day in different years. For the celebrations this year, the Inter- national Association of Buddhist Universities (IABU), created during the UNDV in 2007/2550 by the participating Buddhist higher institutions, plays an important role. The IABU Secretariat now plays a major role in our celebrations, particularly in the academic program of the conference. -

Interfaith Calendar

2018 - 2019 18-month interfaith calendar 18-Month Interfaith Calendar To foster and support inclusive communities, Diversity Awareness Partnership is pleased to present the 2018-2019 18-Month Interfaith Calendar. This publication is a handy guide to observances celebrated across 25 religious traditions in the St. Louis region. When planning your organization’s schedule, refer to our Interfaith Calendar to honor the holidays your friends, neighbors, and colleagues celebrate. Considerations In order to be more accommodating for people who practice different religions, consider the following: FOOD Food and drink are central to many traditions’ rituals and practices. Consider vegetarian, vegan, non-alcoholic, and decaf options, which can accommodate a wide variety of religious and ethical choices. HOURS Some holidays may require individuals to worship or pray during different hours than they may the rest of the year. Consider flexibility that takes into account the work and objectives of your student or employee, rather than the typical time frame when this is normally accomplished. TIME OFF Many organizations have standard holidays for all employees or students that are built around the worldview of a particular religion - Christianity, for example. Consider allowing practitioners of other religions to float these holidays or make shifts in their schedules. Again, the priority should be the quality of the work, not where or when it takes place. DEADLINES/WORK FLOW During holidays that require prayer at late/early hours or that require fasting, some individuals may experience decreased stamina. Examine project schedules or work deadlines to see if they can be adjusted, if need be. PRAYER Some religions require daily or periodic prayer that requires solitude and quiet. -

The Paṭṭhāna (Conditional Relations) and Buddhist Meditation: Application of the Teachings in the Paṭṭhāna in Insight (Vipassanā) Meditation Practice

The Paṭṭhāna (Conditional Relations) and Buddhist Meditation: Application of the Teachings in the Paṭṭhāna in Insight (Vipassanā) Meditation Practice Kyaw, Pyi. Phyo SOAS, London This paper will explore relevance and roles of Abhidhamma, Theravāda philosophy, in meditation practices with reference to some modern Burmese meditation traditions. In particular, I shall focus on the highly mathematical Paṭṭhāna, Pahtan in Burmese, the seventh text of the Abhidhamma Piṭaka, which deals with the functioning of causality and is regarded by Burmese as the most important of the Abhidhamma traditions. I shall explore how and to what extent the teachings in the Paṭṭhāna are applied in insight (vipassanā) meditation practices, assessing the roles of theoretical knowledge of ultimate realities (paramattha-dhammā)1 in meditation. In so doing, I shall attempt to bridge the gap between theoretical and practical aspects of Buddhist meditation. While scholars writing on Theravāda meditation - Cousins,2 King3 and Griffiths4 for example - have focused on distinction between insight meditation (vipassanā) and calm meditation (samatha), this paper will be the first to classify approaches within vipassanā meditation. Vipassanā meditation practices in contemporary Myanmar can be classified into two broad categories, namely, the theoretical based practice and the non- theoretical based practice. Some Burmese meditation masters, Mohnyin Sayadaw Ven. U Sumana (1873-1964)5 and Saddhammaransī Sayadaw Ven. Ashin Kuṇḍalābhivaṃsa (1921- ) and Pa-Auk Sayadaw Ven. Āciṇṇa (1934- ) for example, teach meditators to have theoretical knowledge of ultimate realities. While these meditation masters emphasize theoretical knowledge of the ultimate realities, other meditation masters such as the Sunlun Sayadaw Ven. U Kavi (1878-1952) and the Theinngu Sayadaw Ven. -

The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia

PART 1 THE POPULAR TRADITION ll too often a textbook picture of Theravada Buddhism bears little Aresemblance to the actual practice of Buddhism in Southeast Asia. The lived traditions of Myanmar,1 Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka seem to distort and sometimes subvert the cardinal teachings of nibbana, the Four Noble Truths, or the Noble Eightfold Path familiar to the Western student of Buddhism.2 The observer enters a Theravada Buddhist culture to discover that ordination into the monastic order (sangha) may be motivated more by cultural convention or a young man’s sense of social obligation to his parents rather than the pursuit of transforming wisdom; that the peace and quiet sought by a meditating monk may be overwhelmed by the amplified rock music of a temple festival; that somewhat unkempt village temples outnum- ber tidy, well-organized monasteries; and that the Buddha, austerely imaged in the posture of meditation (hVbVY]^) or dispelling Mara’s powerful army (bVgVk^_VnV) is venerated more in the hope of gaining privilege and prestige, material gain, and protection on journeys than in the hope of nibbana. The apparent contradiction between the highest ideals and goals of Theravada Buddhism and the actual lived tradition in Southeast Asia has long perplexed Western scholars. In his study of Indian religions, Max Weber made a sharp distinction between what he characterized as the “otherworldly mystical” aim of early Indian Buddhism and the world-affirming, practical goals of popular, institutional Buddhism that flourished in -

Handbook of Religious Beliefs and Practices

STATE OF WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES 1987 FIRST REVISION 1995 SECOND REVISION 2004 THIRD REVISION 2011 FOURTH REVISION 2012 FIFTH REVISION 2013 HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES INTRODUCTION The Department of Corrections acknowledges the inherent and constitutionally protected rights of incarcerated offenders to believe, express and exercise the religion of their choice. It is our intention that religious programs will promote positive values and moral practices to foster healthy relationships, especially within the families of those under our jurisdiction and within the communities to which they are returning. As a Department, we commit to providing religious as well as cultural opportunities for offenders within available resources, while maintaining facility security, safety, health and orderly operations. The Department will not endorse any religious faith or cultural group, but we will ensure that religious programming is consistent with the provisions of federal and state statutes, and will work hard with the Religious, Cultural and Faith Communities to ensure that the needs of the incarcerated community are fairly met. This desk manual has been prepared for use by chaplains, administrators and other staff of the Washington State Department of Corrections. It is not meant to be an exhaustive study of all religions. It does provide a brief background of most religions having participants housed in Washington prisons. This manual is intended to provide general guidelines, and define practice and procedure for Washington State Department of Corrections institutions. It is intended to be used in conjunction with Department policy. While it does not confer theological expertise, it will, provide correctional workers with the information necessary to respond too many of the religious concerns commonly encountered. -

Buddhist Modernism and the Rhetoric of Meditative Experience*

BUDDHIST MODERNISM AND THE RHETORIC OF MEDITATIVE EXPERIENCE* ROBERT H. SHARF What we can 't say we can't say and we can't whistle either. Frank Ramsey Summary The category "experience" has played a cardinal role in modern studies of Bud- dhism. Few scholars seem to question the notion that Buddhist monastic practice, particularly meditation, is intended first and foremost to inculcate specific religious or "mystical" experiences in the minds of practitioners. Accordingly, a wide variety of Buddhist technical terms pertaining to the "stages on the path" are subject to a phenomenological hermeneutic-they are interpreted as if they designated discrete "states of consciousness" experienced by historical individuals in the course of their meditative practice. This paper argues that the role of experience in the history of Buddhism has been greatly exaggerated in contemporary scholarship. Both historical and ethnographic evidence suggests that the privileging of experience may well be traced to certain twentieth-century Asian reform movements, notably those that urge a "return" to zazen or vipassana meditation, and these reforms were pro- foundly influenced by religious developments in the West. Even in the case of those contemporary Buddhist schools that do unambiguously exalt meditative experience, ethnographic data belies the notion that the rhetoric of meditative states functions ostensively. While some adepts may indeed experience "altered states" in the course of their training, critical analysis shows that such states do not constitute the reference points for the elaborate Buddhist discourse pertaining to the "path." Rather, such discourse turns out to function ideologically and performatively-wielded more often than not in the interests of legitimation and institutional authority. -

King's Research Portal

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/14639947.2018.1536852 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Kyaw, P. P. (2019). The Sound of the Breath: Sunlun and Theinngu Meditation Traditions of Myanmar. Contemporary Buddhism: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 20(1-2), 247-291. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639947.2018.1536852 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

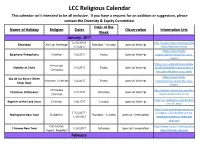

Religious Calendar This Calendar Isn't Intended to Be All Inclusive

LCC Religious Calendar This calendar isn't intended to be all inclusive. If you have a request for an addition or suggestion, please contact the Diversity & Equity Committee. Days of the Name of Holiday Religion Dates Observation Information Link Week January, 2017 12/26/2016 - http://www.history.com/topics/ho Kwanzaa African Heritage Monday - Sunday Special Worship 1/1/2017 lidays/kwanzaa-history https://www.inside- Epiphany/Theophany Christian 1/6/2017 Friday Special Worship mexico.com/ya-vienen-los-reyes- magos/ https://oca.org/saints/lives/2016/ Armenian Nativity of Christ 1/6/2017 Friday Special Worship 12/25/103638-the-nativity-of-our- Orthodox lord-god-and-savior-jesus-christ https://www.inside- Dia de los Reyes (Three Hispanic Christian 1/6/2017 Friday Special Worship mexico.com/ya-vienen-los-reyes- Kings Day) magos/ Orthodox http://www.timeanddate.com/holi Christmas (Orthodox) 1/7/2017 Saturday Special Worship Christian days/russia/christmas-day https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bapt Baptism of the Lord Jesus Christian 1/8/2017 Sunday Special Worship ism_of_Jesus http://www.worldreligionnews.co 1/12/2017 - m/religion-news/buddhism/how- Mahayana New Year Buddhism Thursday - Sunday Special Celebration 1/15/2017 mahayana-buddhists-celebrate- new-year Confucian, http://www.history.com/topics/ho Chinese New Year 1/28/2017 Saturday Special Celebration Daoist, Buddhist lidays/chinese-new-year February http://www.worldreligionnews.co m/religion-news/four-chaplains- Four Chaplains Sunday Interfaith 2/5/2017 Sunday Special Worship sunday-commemorates-priests- -

Sunlun Gu Kyaung Sayadaw

The Life Story of the Sunlun Gu Kyaung Sayadaw This detailed Biography of the Venerable Sunlun Sayadaw U Kawi (*Kavi) was written by the Venerable U Soban™a (pronounced U Thaw-bana in Myanmar), the Vice-presiding Sayadaw (Taik-Oke) of Sunlun Gu Kyaung Monastery, as told by the Venerable Sayadaw U Kawi himself. The man who would be Sunlun Sayadaw U Kawi had, in his many past lives, fervently aspired to be liberated from Samsa‚ra (the innumerable rounds of rebirth), which is like a huge oceanic whirlpool where mind and matter are in continual succession of arising and perishing. He had, in numerous previous lives, done lots of good deeds to achieve that goal. At the time of Kassapa Buddha, the third Buddha of this earth (Badda kappa, the present world, is blessed by five Buddhas), he happened to be a parrot. One day, the parrot (while flying in search of food) saw the Buddha. Though he was an animal, by virtue of his Pa‚ramiƒ with inherent intelligence and wisdom, he knew that this resplendent human before him was a unique noble personage. Wanting to pay homage to the Kassapa Buddha, he flew down to the ground. With his two wings touching on top of his head in reverence, the parrot walked humbly towards the Exalted Buddha, bow down and offered fruits. With great compassion Kassapa Buddha accepted the offering, blessing the parrot with these words, “For this generous charitable deed, whatever your aspiration be, it shall be fulfilled as you so desired.” After saying so, the Buddha walked away. -

SATIPAṬṬHĀNA Il Cammino Diretto

SATIPAṬṬHĀNA Bhikkhu Anālayo SATIPAṬṬHĀNA il cammino diretto Pubblicato per distribuzione gratuita da Santacittarama Edizioni Monastero Buddhista Santacittarama Località Brulla 02030 Poggio Nativo (Rieti) Edizione italiana a cura di Bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā Traduzione di Letizia Baglioni © Bhikkhu Anālayo 2018 Edizione originale in lingua inglese: Satipaṭṭhāna, the direct path to realization, Birmingham, Windhorse Publications, 2003 (ristampa con variazioni minori 2007) Immagine di copertina: Theodor Franz Steffens Copertina: didodolmen Impaginazione: Bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā Stampa: Mediagraf, Noventa Padovana (Padova) ISBN: 9788885706071 Come atto di dhammadāna e in osservanza della regola monastica buddhista, Bhikkhu Anālayo declina l’accettazione di qualsiasi compenso derivante dai diritti d’autore della presente opera INDICE Elenco delle illustrazioni ix Introduzione 1 Traduzione del Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta 3 Capitolo I Aspetti generali del cammino diretto 15 I.1Lo schema del Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta 15 I.2 Panoramica dei quattro satipaṭṭhāna 20 I.3 L’importanza dei singoli satipaṭṭhāna per la realizzazione 23 I.4 Caratteristiche individuali dei satipaṭṭhāna 25 I.5 L’espressione “cammino diretto” 29 I.6 Il termine “satipaṭṭhāna” 31 Capitolo II Il paragrafo di “definizione” del Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta 35 II.1 Contemplare 36 II.2 Cosa significa “essere diligente” (ātāpī) 38 II.3 “Chiaramente cosciente” (sampajāna) 44 II.4 Presenza mentale e chiara coscienza 47 Capitolo III Sati 51 III.1 L’approccio alla conoscenza nel buddhismo antico 51 III.2 Sati 53 III.3 -

Holy Days & Holidays Calendar July 1, 2020

HOLY DAYS & HOLIDAYS CALENDAR JULY 1, 2020 – DECEMBER 31, 2021 JULY 2020 AUGUST 2020 SEPTEMBER 2020 OCTOBER 2020 NOVEMBER 2020 DECEMBER 2020 JANUARY 2021 FEBRUARY 2021 MARCH 2021 APRIL 2021 MAY 2021 JUNE 2021 JULY 2021 AUGUST 2021 SEPTEMBER 2021 OCTOBER 2021 NOVEMBER 2021 DECEMBER 2021 S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 2 3 4 1 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 1 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 18 19 20 21 22 23