Impact of the EU on North-South Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

227Th COMMISSION MEETING Held Via Microsoft Teams

28 September 2020 227th COMMISSION MEETING Held via Microsoft Teams Present: Les Allamby, Chief Commissioner Helen Henderson Jonathan Kearney David A Lavery CB Maura Muldoon Eddie Rooney Stephen White In attendance: David Russell, Chief Executive Rhyannon Blythe, Director (Legal, Research and Investigations, and Advice to Government) Claire Martin, Director (Communications, Information and Education, Public and Political Affairs) Hannah Russell, Director (Legal, Research and Investigations, and Advice to Government) Jacqueline McClintock, Finance, Personnel and Corporate Affairs Officer (Agenda items 1-3) Rebecca Magee, Personal Assistant (Agenda items 3-10) Lorraine Hamill, Director (Finance, Personnel and Corporate Affairs) (Agenda items 5-6) Nikita Brijpaul, Boardroom Apprentice The Chief Commissioner welcomed everyone to the first meeting of the new Commission Board and also welcomed Nikita Brijpaul who is the Commission’s Boardroom Apprentice for 2020-21. 1 1. Apologies and Declarations of Interest 1.1 There were no apologies. 1.2 There were no declarations of interest. 2. Minutes of the 226th Commission meeting and matters arising 2.1 The minutes of the 226th Commission meeting held on 24 August 2020 were agreed as an accurate record. Action: 226th Commission meeting minutes to be uploaded to the website. 2.2. The minutes of the closed meeting held on 24 August 2020 were agreed as an accurate record. 2.3 It was noted that the Chief Commissioner had written to the Northern Ireland Office regarding the Commission’s powers. A copy of the Opinion the Commission had received was also included with the letter. A response has not yet been received (item 2.3 of the 226th minutes refers). -

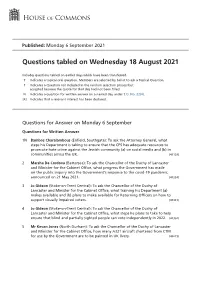

Questions Tabled on Wednesday 18 August 2021

Published: Monday 6 September 2021 Questions tabled on Wednesday 18 August 2021 Includes questions tabled on earlier days which have been transferred. T Indicates a topical oral question. Members are selected by ballot to ask a Topical Question. † Indicates a Question not included in the random selection process but accepted because the quota for that day had not been filled. N Indicates a question for written answer on a named day under S.O. No. 22(4). [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Monday 6 September Questions for Written Answer 1 N Bambos Charalambous (Enfield, Southgate): To ask the Attorney General, what steps his Department is taking to ensure that the CPS has adequate resources to prosecute hate crime against the Jewish community (a) on social media and (b) in communities across the UK. (41129) 2 Marsha De Cordova (Battersea): To ask the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, what progress the Government has made on the public inquiry into the Government's response to the covid-19 pandemic, announced on 21 May 2021. (41224) 3 Jo Gideon (Stoke-on-Trent Central): To ask the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, what training his Department (a) makes available and (b) plans to make available for Returning Officers on how to support visually impaired voters. (41351) 4 Jo Gideon (Stoke-on-Trent Central): To ask the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, what steps he plans to take to help ensure that blind and partially sighted people can vote independently in 2022. -

Lisburn Road, Belfast (Updated May 2021)

Branch Closure Impact Assessment Closing branch: Lisburn Road 364 Lisburn Road Belfast BT9 6GL Closure date: 23/06/2021 The branch your account(s) will be administered from: Belfast City Branch Information correct as at: February 2021 1 What’s in this brochure The world of banking is changing and so are we Page 3 How we made the decision to close this branch What will this mean for our customers? Customers who need more support Access to Banking Standard (updated May 2021) Bank safely – Security information How to contact us Branch information Page 6 Lisburn Road branch facilities Lisburn Road customer profile (updated May 2021) How Lisburn Road customers are banking with us Page 7 Ways for customers to do their everyday banking Page 8 Other Bank of Ireland branches (updated May 2021) Bank of Ireland branches that will remain open Nearest Post Office Other local banks Nearest free-to-use cash machines Broadband available close to this branch Other ways for customers to do their everyday banking Definition of key terms Page 11 Customer and Stakeholder feedback Page 12 Communicating this change to customers Engaging with the local community What we have done to make the change easier 2 The world of banking is changing and so are we Bank of Ireland customers in Northern Ireland have been steadily moving to digital banking over the past 10 years. The pace of this change is increasing. Since 2017, for example, digital banking has increased by 50% while visits to our branches have sharply declined. Increasingly, our customers are using Post Office services with 52% of over-the-counter transactions now made in Post Office branches. -

Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Oral Evidence: Cross Border Co-Operation on Policing, Security and Criminal Justice After Brexit, HC 766

Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Oral evidence: Cross border co-operation on policing, security and criminal justice after Brexit, HC 766 Wednesday 27 January 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 27 January 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Simon Hoare (Chair); Scott Benton; Mr Gregory Campbell; Stephen Farry; Mr Robert Goodwill; Claire Hanna; Fay Jones; Ian Paisley; Stephanie Peacock; Bob Stewart. Questions 254 - 349 Witnesses I: Mark McEwan, Assistant Chief Constable, Police Service of Northern Ireland. II. Paul Morgan CBE, Senior Director, Border Readiness Directorate, Border Force; and Steve Rodhouse, Director-General of Operations, National Crime Agency. Examination of Witness Witness: Mark McEwan. Q254 Chair: Good morning, colleagues. Good morning, Assistant Chief Constable. Thank you for joining us this morning for this session of our inquiry on cross-border co-operation on policing, security and criminal justice post-Brexit. You are very welcome and thank you for joining us. I wonder if you might set the scene for us, if you will, by describing what, if any, differences you have noticed since 1 January. Mark McEwan: Good morning. By and large, it is a little too early to say on a lot of these areas. I will come first to justice and home affairs matters. In terms of our legislative vehicles that were discussed previously at this Committee, we maintain the ECRIS system, which translates into UK-CRIS now, so that runs as was, effectively. In terms of Europol, we still have access to SIENA and to Eurojust. The UK has embeddedness in those organisations and we are still able to access the JITs for joint investigation. -

The Brexit Effect? Ethno-National Divisions on the Island of Ireland Among Political Elites and the Youth

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The Brexit Effect? Ethno-National Divisions on the Island of Ireland among Political Elites and the Youth O'Connell, Barry; Medeiros, M. DOI 10.1080/13537113.2020.1827724 Publication date 2020 Document Version Final published version Published in Nationalism & Ethnic Politics License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): O'Connell, B., & Medeiros, M. (2020). The Brexit Effect? Ethno-National Divisions on the Island of Ireland among Political Elites and the Youth. Nationalism & Ethnic Politics, 26(4), 389-404. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2020.1827724 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 -

Gender and Brexit the Performance of Toxic Masculinity in House of Commons Debates During the Brexit Process

Gender and Brexit the performance of toxic masculinity in House of Commons debates during the Brexit process Evelien Müller | 4688325 Radboud University Bachelor Thesis Prof. dr. Anna van der Vleuten 3 July 2020 Müller, 4688325/1 [door docent op te nemen op elk voorblad van tentamens] Integriteitscode voor studenten bij toetsen op afstand De Radboud Universiteit wil bijdragen aan een gezonde en vrije wereld met gelijke kansen voor iedereen. Zij leidt daartoe studenten op tot gewetensvolle, betrokken, kritische en zelfbewuste academici. Daarbij hoort een houding van betrouwbaarheid en integriteit. Aan de Radboud Universiteit gaan wij er daarom van uit dat je aan je studie bent begonnen, omdat je daadwerkelijk kennis wilt opdoen en je inzicht en vaardigheden eigen wilt maken. Het is essentieel voor de opbouw van je opleiding (en daarmee voor je verdere loopbaan) dat jij de kennis, inzicht en vaardigheden bezit die getoetst worden. Wij verwachten dus dat je dit tentamen op eigen kracht maakt, zonder gebruik te maken van hulpbronnen, tenzij dit is toegestaan door de examinator. Wij vertrouwen erop dat je tijdens deelname aan dit tentamen, je houdt aan de geldende wet- en regelgeving, en geen identiteitsfraude pleegt, je niet schuldig maakt aan plagiaat of andere vormen van fraude en andere studenten niet frauduleus bijstaat. Verklaring fraude en plagiaat tentamens Faculteit der Letteren Door dit tentamen te maken en in te leveren verklaar ik dit tentamen zelf en zonder hulp van anderen gemaakt te hebben. Ik verklaar bovendien dat ik voor dit tentamen geen gebruik heb gemaakt van papieren en/of digitale bronnen, notities, opnames of welke informatiedragers ook (tenzij nadrukkelijk vooraf door de examinator toegestaan) en geen overleg heb gepleegd met andere personen. -

Northern Ireland (Ministers, Elections and Petitions of Concern) Bill (Committee Stage Decisions)

Committee Stage: Tuesday 6 July 2021 Northern Ireland (Ministers, Elections and Petitions of Concern) Bill (Committee Stage Decisions) This document sets out the fate of each clause, schedule, amendment and new clause considered at committee stage. A glossary with key terms can be found at the end of this document. First to Third Sittings FIRST AND SECOND SITTINGS Mr Robin Walker Agreed to That— 1. the Committee shall (in addition to its first meeting at 9.25 am on Tuesday 29 June) meet— (a) at 2.00 pm on Tuesday 29 June; (b) at 9.25 am and 2.00 pm on Tuesday 6 July; (c) at 11.30 am and 2.00 pm on Thursday 8 July; 2. the Committee shall hear oral evidence in accordance with the following Table: Date Time Witness Tuesday 29 June Until no later than The Committee on the Administration of 10.30 am Justice; Professor Jonathan Tonge, University of Liverpool Tuesday 29 June Until no later than Lilah Howson-Smith 11.25 am Tuesday 29 June Until no later than Sir Jonathan Stephens 2.30 pm Tuesday 29 June Until no later than Emma Little-Pengelly 3.15 pm Tuesday 29 June Until no later than Mark Durkan 4.00 pm 2 Tuesday 6 July 2021 COMMITTEE STAGE Date Time Witness Tuesday 29 June Until no later than Alan Maskey, Speaker of the Northern 4.45 pm Ireland Assembly; Lesley Hogg, Clerk of the Northern Ireland Assembly; Dr Gareth McGrath, Director of Parliamentary Services, Northern Ireland Assembly 3. the proceedings shall (so far as not previously concluded) be brought to a conclusion at 5.00 pm on Thursday 8 July. -

Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Oral Evidence: Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol, HC 767

Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Oral evidence: Brexit and the Northern Ireland protocol, HC 767 Wednesday 16 September 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 16 September 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Simon Hoare (Chair); Caroline Ansell; Scott Benton; Mr Gregory Campbell; Stephen Farry; Mary Kelly Foy; Mr Robert Goodwill; Claire Hanna; Ian Paisley; Stephanie Peacock. Questions 1 - 114 Witnesses I: Rt Hon Brandon Lewis MP, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland; Colin Perry, Economy Director, Northern Ireland Office. Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Rt Hon Brandon Lewis MP and Colin Perry. Q1 Chair: Good morning, colleagues, Secretary of State and Mr Perry. Thank you for joining us this morning for what can only be described as a topical session on the protocol and, allied with that, the Internal Market Bill. Secretary of State, good morning. I just wondered: what question does Lord Keen think you were answering at the UQ last week? Brandon Lewis: I have spoken to Lord Keen. I have to say that, in talking to Lord Keen and looking at the specific question that my hon. Friend asked me last week, he agrees that the answer I gave was the correct answer, and it outlined and confirmed the legal advice that was published to you and others by the Attorney General last week. Q2 Chair: So you were answering the question. In a limited way, the proposals do breach international legal agreements. Brandon Lewis: The Government’s legal advice from the Attorney General, which was published to you last week, is very clear on this. -

Early Day Motions Tabled on Thursday 17 June 2021

Published: Friday 18 June 2021 Early Day Motions tabled on Thursday 17 June 2021 Early Day Motions (EDMs) are motions for which no days have been fixed. The number of signatories includes all members who have added their names in support of the Early Day Motion (EDM), including the Member in charge of the Motion. EDMs and added names are also published on the EDM database at www.parliament.uk/edm [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. New EDMs 214 Retirement of East Lothian teacher Sheila Laing after 45 years' service Tabled: 17/06/21 Signatories: 1 Kenny MacAskill That this House applauds the dedicated work of East Lothian's first virtual headteacher Sheila Laing, who is retiring after 45 years as a teacher; pays tribute to her outstanding supportive and innovative work with care experienced young people; acknowledges the recent challenging time for teachers and their incredible hard work in continuing to provide excellent education and experiences for all of East Lothian pupils throughout the covid-19 outbreak; notes in particular Sheila's commitment to listen and discover what is important to care experienced children and help them find ways to achieve their ambitions; and wishes Sheila a long and happy retirement. 215 Windrush Day 2021 Tabled: 17/06/21 Signatories: 14 Helen Hayes Florence Eshalomi Caroline Lucas Sir Peter Bottomley Paula Barker Dame Margaret Hodge Valerie Vaz Colum Eastwood Jeremy Corbyn Mr Virendra Sharma Carol Monaghan Paul Blomfield Allan Dorans Joanna Cherry That this House notes that 22 June -

Find Your Local MP

Find your local MP East Antrim East Londonderry Acorn Integrated Primary Carhill Integrated Primary Carnlough Integrated Primary Mill Strand Integrated Primary Corran Integrated Primary Roe Valley Integrated Primary Ulidia Integrated College North Coast Integrated College MP MP Sammy Wilson (DUP) Gregory Campbell DUP 116 Main Street, Larne, BT40 1RG 25 Bushmills Road, Coleraine, BT52 2BP 028 2826 7722 028 7032 7327 [email protected] [email protected] Fermanagh and East Belfast South Tyrone Lough View Integrated Primary Enniskillen Integrated Primary Windmill Integrated Primary MP Erne Integrated College Gavin Robinson DUP Integrated College Dungannon House of Commons, London, SW1A 0AA 020 7219 8746 MP [email protected] Michelle Gildernew Sinn Fein House of Commons, London, SW1A 0AA 020 7219 1759 [email protected] Foyle Mid Ulster Groaty Integrated Primary Phoenix Integrated Primary Oakgrove Integrated Primary Spires Integrated Primary Oakgrove Integrated College Sperrin Integrated College MP Colum Eastwood SDLP MP House of Commons, London, SW1A 0AA Francie Molloy Sinn Fein 26 Burn Road, Cookstown, Co Tyrone, BT80 8DN 028 8676 5850 [email protected] Lagan Valley Newry and Fort Hill Integrated Primary Oakwood Integrated Primary Armagh Rowandale Integrated Primary Fort Hill Integrated College Saints & Scholars Integrated Primary MP Sir Jeffrey Donaldson DUP MP The Old Town Hall, 29 Castle Street, Mickey Brady Sinn Fein Lisburn, BT27 4DH House of Commons, London, SW1A 0AA 028 9266 8001 020 -

Committees of the Northern Ireland Assembly, 2016

Northern Ireland Assembly MEMBERSHIP OF STATUTORY COMMITTEES NIA 1/16-21 MEMBERSHIP OF STATUTORY COMMITTEES CONTENTS Section Heading Page No. Committee for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs 3 Committee for Communities 4 Committee for the Economy 5 Committee for Education 6 Committee for the Executive Office 7 Committee for Finance 8 Committee for Health 9 Committee for Infrastructure 10 Committee for Justice 11 NIA 1/16-21 2 COMMITTEE FOR AGRICULTURE, ENVIRONMENT AND RURAL AFFAIRS Linda Dillon (SF) (Chairperson) Caoimhe Archibald (SF) (Deputy Chairperson) Committee Members: David Ford (All) Sydney Anderson (DUP) Maurice Bradley (DUP) Edwin Poots (DUP) George Robinson (DUP) Oliver McMullan (SF) Patsy McGlone (SDLP) Harold McKee (UUP) Robin Swann (UUP) NIA 1/16-21 3 COMMITTEE FOR COMMUNITIES Colum Eastwood (SDLP) (Chairperson) Michelle Gildernew (SF) (Deputy Chairperson) Committee Members: Naomi Long (All) Jonathan Bell (DUP) Adrian McQuillan (DUP) Christopher Stalford (DUP) Steven Agnew (GP) Fra McCann (SF) Carál Ní Chuilín (SF) Nichola Mallon (SDLP) Andy Allen (UUP) NIA 1/16-21 4 COMMITTEE FOR THE ECONOMY Conor Murphy (SF) (Chairperson) Steve Aiken (UUP) (Deputy Chairperson) Committee Members: Stephen Farry (All) Tom Buchanan (DUP) Gordon Dunne (DUP) Gordon Lyons (DUP) Mervyn Storey (DUP) Caoimhe Archibald (SF) Alex Maskey (SF) Sinead Bradley (SDLP) Alan Chambers (UUP) NIA 1/16-21 5 COMMITTEE FOR EDUCATION Barry McElduff (SF) (Chairperson) Chris Lyttle (All) (Deputy Chairperson) Committee Members: David Hilditch (DUP) Carla Lockhart -

Fortnight Magazine

april 2021 issue 481 april 50 2021 FORTNIGHT@ politics, arts & culture in northern ireland FORT NIGHT @ 5 0 Problems with the Independents build communities Protocol How the side effects can be mitigated by Rory Montgomery The standoffs and failures in Brussels by Bernard Conlon New trade opportunities by Edgar Morgenroth Student discounts Personalised service Author events more than just Supporting local artists Also in this issue: Aaron Edwards on the response from books Sole distributors of Fortnight at 50 Loyalists, Jamie Pow on the need for Unionist bridge-building and issue Claire Mitchell on attitudes to the NHS 83 Botanic Avenue, Belfast, BT7 1JL 481 In the Arts pages: Rosemary Jenkinson looks for a Protestant @noalibisbooks Tel: +44 2890 319 601 Heaney, Malachi O’Doherty on Northern humour, with prose and Email: [email protected] www.noalibis.com @noalibisbookstore poetry from new writers Contents ortnight @50 Editorial 1 Politics Rory Montgomery: Protocol problems for both Sovreignty, Good Friday parts of Ireland: North and South 2 and the Protocol Bernard Conlon: Britain, Ireland and Europe: f Vacillating and vitriol over vaccines 6 The purpose of the Ireland/Northern Ireland Edgar Morgenroth: NI Protocol, a view from Dublin 9 Protocol was and is to protect the terms of the Andy Pollak: Why I don’t believe in Border Polls 11 Good Friday Agreement and with it the rights and Aaron Edwards: Leaders and followers in interests of all the people in both parts of Ireland. Ulster Unionism 14 The current and continuing standoffs between the Jamie Pow: The bridges unionists need to build 16 United Kingdom and European Union and their Connal Parr: The SDLP at 50 18 interpretation of its terms is not achieving that.