Witczuk, J., S. Pagacz, J. Gliwicz and L.S. Mills. 2015. Niche Overlap Between Sympatric Coyotes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geologic History of Siletzia, a Large Igneous Province in the Oregon And

Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot Wells, R., Bukry, D., Friedman, R., Pyle, D., Duncan, R., Haeussler, P., & Wooden, J. (2014). Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot. Geosphere, 10 (4), 692-719. doi:10.1130/GES01018.1 10.1130/GES01018.1 Geological Society of America Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Downloaded from geosphere.gsapubs.org on September 10, 2014 Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot Ray Wells1, David Bukry1, Richard Friedman2, Doug Pyle3, Robert Duncan4, Peter Haeussler5, and Joe Wooden6 1U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefi eld Road, Menlo Park, California 94025-3561, USA 2Pacifi c Centre for Isotopic and Geochemical Research, Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, 6339 Stores Road, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada 3Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 1680 East West Road, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA 4College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, 104 CEOAS Administration Building, Corvallis, Oregon 97331-5503, USA 5U.S. Geological Survey, 4210 University Drive, Anchorage, Alaska 99508-4626, USA 6School of Earth Sciences, Stanford University, 397 Panama Mall Mitchell Building 101, Stanford, California 94305-2210, USA ABSTRACT frames, the Yellowstone hotspot (YHS) is on southern Vancouver Island (Canada) to Rose- or near an inferred northeast-striking Kula- burg, Oregon (Fig. -

New Titles for Spring 2021 Green Trails Maps Spring

GREEN TRAILS MAPS SPRING 2021 ORDER FORM recreation • lifestyle • conservation MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS [email protected] 800.553.4453 ext. 2 or fax 800.568.7604 Outside U.S. call 206.223.6303 ext. 2 or fax 206.223.6306 Date: Representative: BILL TO: SHIP TO: Name Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Phone Email Ship Via Account # Special Instructions Order # U.S. DISCOUNT SCHEDULE (TRADE ONLY) ■ Terms: Net 30 days. 1 - 4 copies ........................................................................................ 20% ■ Shipping: All others FOB Seattle, except for orders of 25 books or more. FREE 5 - 9 copies ........................................................................................ 40% SHIPPING ON BACKORDERS. ■ Prices subject to change without notice. 10 - 24 copies .................................................................................... 45% ■ New Customers: Credit applications are available for download online at 25 + copies ................................................................45% + Free Freight mountaineersbooks.org/mtn_newstore.cfm. New customers are encouraged to This schedule also applies to single or assorted titles and library orders. prepay initial orders to speed delivery while their account is being set up. NEW TITLES FOR SPRING 2021 Pub Month Title ISBN Price Order February Green Trails Mt. Jefferson, OR No. 557SX 9781680515190 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass, WA No. 207SX 9781680515343 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Wasatch Front Range, UT No. 4091SX 9781680515152 18.00 _____ TOTAL UNITS ORDERED TOTAL RETAIL VALUE OF ORDERED An asterisk (*) signifies limited sales rights outside North America. QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE WASHINGTON ____ 9781680513448 Alpine Lakes East Stuart Range, WA No. 208SX $18.00 ____ 9781680514537 Old Scab Mountain, WA No. 272 $8.00 ____ ____ 9781680513455 Alpine Lakes West Stevens Pass, WA No. -

Expedition Descriptions

BOLD & GOLD EXPEDITION DESCRIPTIONS BOYS AND GIRLS OUTDOOR LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT AT THE YMCA OF GREATER SEATTLE BOLD & GOLD EXPEDITION DESCRIPTIONS 1 WELCOME FROM THE BOLD & GOLD TEAM! To Our Old and New Friends, Welcome to our community! You have taken the first step to discovering what you are truly capable of. BOLD & GOLD is a program that will guide you to find the strength in yourself, in the community around you and in the outdoors. Whether it is exploring the old growth forest of North Cascades National Park, backpacking along the wild coastline of Olympic National Park, or summiting Mount Baker, you will have the opportunity to explore the beauty of nature, overcome challenges, try new things, and create lifelong friendships. We applaud you for taking the first step. While navigating the challenges of travel in the wilderness, we will help you embrace multicultural leadership by combining your unique self and our program’s values. You now have the chance to live beyond your wildest dreams! Thank you for seizing this opportunity and we look forward to hearing your stories when you return. In the words of Dr. Seuss: “You’re off to Great Places! Today is your day! Your mountain is waiting, So... get on your way!” - See you soon! The BOLD & GOLD Team TABLE OF CONTENTS BOLD | 1-WEEK EXPEDITIONS 3 MAKE A SCENE: ART AND BACKPACKING IN THE NORTH CASCADES . 13 BACKPACKING AND FISHING IN THE NORTH CASCADES . 3 POETS AND PEAKS: EXPLORING WILD PLACES THROUGH BEYOND CITY LIMITS: CAMPING AND HIKING AT MT. RAINIER CREATIVE WRITING . -

Olympic Peninsula Tourism Commission 2019 Media Kit

Olympic Peninsula Tourism Commission 2019 Media Kit Hoh Rain Forest, Olympic National Park Located in Washington’s northwest corner, the Olympic Peninsula is a land like no other. It is both environmentally and culturally rich. From the jigsaw coastlines, temperate rainforest, and glacial-capped peaks of Olympic National Park to the organic farms and wineries of the Dungeness and Chimacum Valleys; from the cultural centers of native tribes dotting the Highway 101 Pacific Coast Scenic Byway to the maritime history of its port towns, there’s an adventure for every age and spirit here. Holiday Lights Blyn, WA Olympic National Park A Modern-day Eden The Olympic Peninsula is home to the 1,400 square mile Olympic National Park. A designated UNESCO World Heritage Site and International Biosphere Reserve, the park has three distinctly different ecosystems; the Pacific coastline, the Olympic Mountains and the primeval rain forests. In 1976, Olympic became an International Biosphere Reserve; and in 1981, it was designated a World Heritage Site. These diverse ecosystems are still largely pristine due to its wilderness designations. The wild and rugged coastline along the Pacific Ocean stretches over 70 miles and is the longest undeveloped coast in the contiguous United States. The extensive alpine forests are home to some of the world’s largest conifers, towering 300 feet tall and measuring 25 feet around. Among the ancient forests of old-growth trees exists the largest temperate rainforest on the earth. Found on the Pacific Coast of North America, stretching from Oregon to Alaska. The rugged Olympic Mountains, home to Mount Olympus and over 60 glaciers, are thought to be beautiful enough for the gods to dwell. -

Petrogenesis of Siletzia: the World’S Youngest Oceanic Plateau

Results in Geochemistry 1 (2020) 100004 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Results in Geochemistry journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ringeo Petrogenesis of Siletzia: The world’s youngest oceanic plateau T.Jake R. Ciborowski a,∗, Bethan A. Phillips b,1, Andrew C. Kerr b, Dan N. Barfod c, Darren F. Mark c a School of Environment and Technology, University of Brighton, Brighton BN2 4GJ, UK b School of Earth and Ocean Science, Cardiff University, Main Building, Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3AT, UK c Natural Environment Research Council Argon Isotope Facility, Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre, East Kilbride G75 0QF, UK a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Keywords: Siletzia is an accreted Palaeocene-Eocene Large Igneous Province, preserved in the northwest United States and Igneous petrology southern Vancouver Island. Although previous workers have suggested that components of Siletzia were formed Geochemistry in tectonic settings including back arc basins, island arcs and ocean islands, more recent work has presented Geochemical modelling evidence for parts of Siletzia to have formed in response to partial melting of a mantle plume. In this paper, we Mantle plumes integrate geochemical and geochronological data to investigate the petrogenetic evolution of the province. Oceanic plateau Large igneous provinces The major element geochemistry of the Siletzia lava flows is used to determine the compositions of the primary magmas of the province, as well as the conditions of mantle melting. These primary magmas are compositionally similar to modern Ocean Island and Mid-Ocean Ridge lavas. Geochemical modelling of these magmas indicates they predominantly evolved through fractional crystallisation of olivine, pyroxenes, plagioclase, spinel and ap- atite in shallow magma chambers, and experienced limited interaction with crustal components. -

Olympic Marmot (Marmota Olympus)

Candidate Species ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Olympic Marmot (Marmota olympus) State Status: Candidate, 2008 Federal Status: None Recovery Plans: None The Olympic marmot is an endemic species, found only in the Olympic Mountains of Washington (Figure 1). It inhabits subalpine and alpine meadows and talus slopes at elevations from 920-1,990 m (Edelman 2003). Its range is largely contained within Olympic National Park. The Olympic marmot was added Figure 1. Olympic marmot (photo by Rod Gilbert). to the state Candidate list in 2008, and was designated the State Endemic Mammal by the Washington State Legislature in 2009. The Olympic marmot differs from the Vancouver Island marmot (M. vancouverensis), in coat color, vocalization, and chromosome number. Olympic marmots were numerous during a 3-year study in the 1960s, but in the late 1990s rangers began noticing many long-occupied meadows no longer hosted marmots. Olympic marmots differ from most rodents by having a drawn out, ‘K-selected’ life history; they are not reproductively mature until 3 years of age, and, on average, females do not have their first litter until 4.5 years of age. Marmots can live into their teens. Data from 250 ear-tagged and 100 radio-marked animals indicated that the species was declining at about 10%/year at still-occupied sites through 2006, when the total population of Olympic marmots was thought to be fewer than 1,000 animals. During 2007-2010, a period of higher snowpack, marmot survival rates improved and numbers at some well-studied colonies stabilized. Human disturbance and disease were ruled out as causes, but the decline was apparently due to low survival of females (Griffin 2007, Griffin et al. -

Cougar--Human Encounters

COUGAR--HUMAN ENCOUNTERS: A SEARCH FOR THE FACTS by Debbie D. Carnevali A Thesis Submitt ed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Environmental Studies December 1998 This Thesis for the Master ofEnvironmental Studies Degree by Debbie D. Carnevali has been approved for The Evergreen State College by d~ I!(?d;~ DR . JOHN PERKINS Member ofthe Faculty ANNA BRUCE Wildlife Biologist Date ABSTRACT Washington State is the home ofNorth America's largest feline carnivore, the cougar, Felis concotor. This species is difficult to study because ofits secre tive, solitary and nocturnal nature which gives it an air of mystery and fosters fear. The cougar was thrust into the public limelight two years ago when Initiative 655 was passed by Washington voters. The Initiative banned the use of hounds for hunting cougar and several other species. Populations have increased since the bounty days before cougars were given game status and management protection. Increases in mountain lion sightings and encounters have raised the quest ion whether the increase is due solely to the two year old ban on hound hunting . The topic ofcougar-human encounters is complex and varied. The issues include human population growth, habitat destruction and fragmentation, social and political views on carnivores, intolerance, and people' s fear due to misinformation regarding cougars and their behavior. Cougar biology, population dynamics and cougar management in twelve states and two Canadian provinces (British Columbia and Alberta) were analyzed for this report. This review found that increases in cougar sightings and encounters are greatest in areas ofrapid human population growth where intru sion into cougar habitat occurs. -

The Olympic Mountains Experiment (Olympex)

THE OLYMPIC MOUNTAINS EXPERIMENT (OLYMPEX) ROBERT A. HOUZE JR., LYNN A. MCMURDIE, WALTER A. PETERSEN, MATHEW R. SCHWAllER, WIllIAM BACCUS, JESSICA D. LUNDQUIST, CLIFFORD F. MASS, BART NIJSSEN, STEVEN A. RUTLEDGE, DAVID R. HUDAK, SIMONE TANEllI, GERALD G. MACE, MICHAEL R. POEllOT, DENNIS P. LETTENMAIER, JOSEph P. ZAGRODNIK, ANGELA K. ROWE, JENNIFER C. DEHART, LUKE E. MADAUS, AND HANNAH C. BARNES OLYMPEX is a comprehensive field campaign to study how precipitation in Pacific storms is modified by passage over coastal mountains. hen frontal systems pass over midlatitude the lee sides. Snow deposited at high elevations by mountain ranges, precipitation is modified, these storms is an important form of water storage Woften with substantial enhancement on the around the globe. However, precipitation over and windward slopes and reduced accumulations on near Earth’s mountain ranges has long been very difficult to measure. As a result, the physical and dynamical mechanisms of enhancement and reduc- AFFILIATIONS: HOUZE, MCMURDIE, LUNDQUIST, MASS, NIJSSEN, tion of precipitation accompanying storm passage ZAGRODNIK, ROWE, AND DEHART—University of Washington, over mountains remain only partially understood. Seattle, Washington; PETERSON—NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama; SCHWAllER—NASA Goddard Space The launch of the Global Precipitation Measurement Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland; HOUZE AND BARNES—Pa- (GPM) satellite in February 2014 by the U.S. National cific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington; Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and BACCUS—Olympic National Park, Port Angeles, Washington; the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (Hou et al. RUTLEDGE—Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado; 2014) fosters exploration of precipitation processes HUDAK—Environment and Climate Change Canada, King City, over most of Earth’s mountain ranges. -

High-Pressure Metamorphism and Uplift of the Olympic Subduction Complex

High-pressure metamorphism and uplift of the Olympic subduction complex Mark T. Brandon, Arthur R. Calderwood* Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, P.O. Box 6666, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 ABSTRACT The discovery of the critical �mblage lawsonite + quartz + calcite indicates that a significant part of the Cenozoic Olympic subduction complex of northwestern Washington State formed by underplating at a depth of about 11 km. The deep structural level exposed in this area is attributed to the presence of a 10-km-high arch in the underlying Juan de Fuca plate. We postulate that this arch was formed when the southern Cordilleran coastline swung westward as a result of middle Miocene to recent extension in the Basin and Range province. INTRODUCTION Olympic subduction complex accumulated by the western Olympic subduction complex and The Cascadia convergent margin, which subduction underplating. In this paper we exam that of Hawkins (1967) on prehnite-bearing flanks the western side of Oregon, Washington, ine the metamorphic and uplift history of this rocks in the Mount Olympus area (MO in Fig. and Vancouver Island, marks the subduction subduction complex and postulate a new inter l ). Zones in the remaining areas were delimited boundary between North America and the Juan pretation for formation of the Olympic uplift. using samples collected during their mapping de Fuca plate. Along much of this margin, the (Tabor and Cady, 1978b) in the central and fore-arc region is underlain by a flat to gently METAMORPHISM OF THE eastern Olympic Peninsula. dipping sheet of lower Eocene basalt (Crescent, OLYMPIC SUBDUCTION COMPLEX We have examined thin sections from 138 Siletz, and correlative formations; Wells et al., Tabor and Cady (l978b) delimited a general sandstone samples from all parts of the Olympic 1984), which represents the basement on which metamorphic zonation decreasing in grade from subduction complex; most, however, are from a subsequent fore-arc basin has accumulated east to west. -

Remote Sensing of Nearshore Vegetation in Washington State's

Remote Sensing of Nearshore Vegetation in Washington State's Puget Sound,...ngton State's Department of Natural Resources' Aquatic Resources Division In: Proceedings of 1997 Geospatial Conference, Seattle, WA, volume 3, pp. 527 Remote Sensing of Nearshore Vegetation in Washington State's Puget Sound Rebecca Ritter (remote sensing analyst) and Elizabeth L. Lanzer (GIS coordinator) Washington State Department of Natural Resources 1111 Washington St. SE PO Box 47027 Olympia, WA 98504-7027 ABSTRACT The Washington State Department of Natural Resources, in cooperation with other state and federal agencies, has developed a program to remotely sense nearshore vegetation (intertidal and shallow subtidal). The classified nearshore data are integrated into an existing geographic information system for spatial analysis to support aquatic land use planning and management decisions. In 1996, a data set for the greater Bellingham Bay area in Northern Puget Sound was completed. Program methods incorporate advances in remote sensing technologies to overcome the constraints of the target geography, which prevent the use of more traditional inventory methods. The multispectral image data were collected by a Compact Airborne Spectrographic Imager (CASI) sensor, configured to collect 11 bands of data (from the visible to the near infrared range) with square, four meter pixels. Color infrared (CIR) photography was acquired simultaneously from the same aerial platform. Marine scientists collected field data located by a differential Global Positioning System (DGPS) or annotated aerial photographs during the same season as the image data were collected. A hybrid of supervised and unsupervised image classification techniques produced mapping of eight vegetation types. Field data were used to conduct a classification accuracy assessment. -

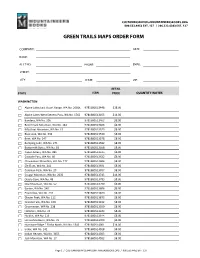

Green Trails Maps Order Form

[email protected] 800.553.4453 EXT. 137 / 206.223.6303 EXT. 137 GREEN TRAILS MAPS ORDER FORM COMPANY: DATE: NAME: ACCT NO: PHONE: EMAIL: STREET: CITY: STATE: ZIP: RETAIL STATE ISBN PRICE QUANTITY/NOTES WASHINGTON □ Alpine Lakes East Stuart Range, WA No. 208SX 9781680513448 $18.00 □ Alpine Lakes West Stevens Pass, WA No. 176S 9781680513455 $14.00 □ Bandera, WA No. 206 9781680513462 $8.00 □ Benchmark Mountain, WA No. 144 9781680513486 $8.00 □ Billy Goat Mountain, WA No. 19 9781680513523 $8.00 □ Blue Lake, WA No. 334 9781680513530 $8.00 □ Brief, WA No. 147 9781680513578 $8.00 □ Bumping Lake, WA No. 271 9781680513592 $8.00 □ Buttermilk Butte, WA No. 83 9781680513608 $8.00 □ Cape Flattery, WA No. 98S 9781680513615 $8.00 □ Cascade Pass, WA No. 80 9781680513622 $8.00 □ Chiwaukum Mountain, WA No. 177 9781680513684 $8.00 □ Cle Elum, WA No. 241 9781680513691 $8.00 □ Coleman Peak, WA No. 20 9781680513707 $8.00 □ Cougar Mountain, WA No. 203S 9781680513745 $14.00 □ Diablo Dam, WA No. 48 9781680513783 $8.00 □ Doe Mountain, WA No. 52 9781680513790 $8.00 □ Easton, WA No. 240 9781680513806 $8.00 □ Enumclaw, WA No. 237 9781680513820 $8.00 □ Glacier Peak, WA No. 112 9781680513875 $8.00 □ Granite Falls, WA No. 109 9781680513912 $8.00 □ Greenwater, WA No. 238 9781680513929 $8.00 □ Hamilton, WA No. 45 9781680513943 $8.00 □ Holden, WA No. 113 9781680513974 $8.00 □ Horseshoe Basin, WA No. 21 9781680513998 $8.00 □ Hurricane Ridge * Elwha North, WA No. 134S 9781680514001 $14.00 □ Index, WA No. 142 9781680514018 $8.00 □ Indian Heaven, WA No. 365S 9781680514025 $8.00 □ Jack Mountain, WA No. -

Draft Mountain Goat Management Plan / Environmental Impact

Chapter 3: Affected Environment CHAPTER 3: AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT INTRODUCTION The “Affected Environment” describes existing conditions for those elements of the natural and cultural environments that could be affected by implementing the alternatives considered in this Mountain Goat Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement (plan/EIS). These include (1) areas of Olympic National Park and Olympic National Forest on the Olympic Peninsula, from where mountain goats could be removed; and (2) areas in the North Cascades national forests, where mountain goats could be translocated. This Affected Environment chapter is therefore divided into two subsections addressing the affected environment of the Olympic Peninsula in Part One, followed by the North Cascades national forests in Part Two. On the Olympic Peninsula, mountain goat habitat comprises approximately 150,000 acres of high- elevation alpine and subalpine lands that are free of glacial ice and above 4,675 feet in elevation and within approximately 360 feet of steep rocky slopes (Jenkins et al. 2011a, 2016). Therefore, management activities associated with this plan/EIS would take place primarily above 4,000 feet, but some activity could take place in lower elevation areas during winter months. Management activities associated with alternatives B, C, and D would require multiple staging areas (as described in chapter 2) located strategically on both National Park Service (NPS) and National Forest System (NFS) lands. The discussion of the affected environment is limited to only those resources that may be affected by actions taken in identified mountain goat habitat and surrounding the staging areas (see figure 5 in chapter 2). The natural environment components addressed in this plan/EIS for the Olympic Peninsula include mountain goats, wilderness character, wildlife and wildlife habitat, vegetation, threatened or endangered species, acoustic environment, and soils.