International Alert's Tajikistan Case Study, Climate Change, Complexity and Resilient Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON THE INSTALLMENT OF SMALL HYDROPOWER STATIONS FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF KHATLON OBLAST IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FINAL REPORT September 2012 Japan International Cooperation Agency NEWJEC Inc. E C C CR (1) 12-005 Final Report Contents, List of Figures, Abbreviations Data Collection Survey on the Installment of Small Hydropower Stations for the Communities of Khatlon Oblast in the Republic of Tajikistan FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Summary Chapter 1 Preface 1.1 Objectives and Scope of the Study .................................................................................. 1 - 1 1.2 Arrangement of Small Hydropower Potential Sites ......................................................... 1 - 2 1.3 Flowchart of the Study Implementation ........................................................................... 1 - 7 Chapter 2 Overview of Energy Situation in Tajikistan 2.1 Economic Activities and Electricity ................................................................................ 2 - 1 2.1.1 Social and Economic situation in Tajikistan ....................................................... 2 - 1 2.1.2 Energy and Electricity ......................................................................................... 2 - 2 2.1.3 Current Situation and Planning for Power Development .................................... 2 - 9 2.2 Natural Condition ............................................................................................................ -

TAJIKISTAN TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock

APPENDIX 15 TAJIKISTAN 870 км TAJIKISTAN 414 км Sangimurod Murvatulloev 1161 км Dushanbe,Tajikistan / [email protected] Tel: (992 93) 570 07 11 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) 1206 км Shiraz, Islamic Republic of Iran 3 651 . 9 - 13 November 2008 Общая протяженность границы км Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock - 2007 Territory - 143.000 square km Cities Dushanbe – 600.000 Small Population – 7 mln. Khujand – 370.000 Capital – Dushanbe Province Cattle Dairy Cattle ruminants Yak Kurgantube – 260.000 Official language - tajiki Kulob – 150.000 Total in Ethnic groups Tajik – 75% Tajikistan 1422614 756615 3172611 15131 Uzbek – 20% Russian – 3% Others – 2% GBAO 93619 33069 267112 14261 Sughd 388486 210970 980853 586 Khatlon 573472 314592 1247475 0 DRD 367037 197984 677171 0 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) Country – Livestock - 2007 Current FMD Situation and Trends Density of sheep and goats Prevalence of FM D population in Tajikistan Quantity of beans Mastchoh Asht 12827 - 21928 12 - 30 Ghafurov 21929 - 35698 31 - 46 Spitamen Zafarobod Konibodom 35699 - 54647 Spitamen Isfara M astchoh A sht 47 -

Republic of Tajikistan

E4132 REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Land Management and Rural Livelihoods Project (ELMARL) Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Public Disclosure Authorized December 2012 Public Disclosure Authorized 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary. ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Background ..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. Country Context ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 2. Project Description .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 2.1. Project Objectives ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Key Results .............................................................................................................................................................. 7 -

Social and Ecological Aspects of the Water Resources Management of the Transboundary Rivers of Central Asia

Evolving Water Resources Systems: Understanding, Predicting and Managing Water–Society Interactions 441 Proceedings of ICWRS2014, Bologna, Italy, June 2014 (IAHS Publ. 364, 2014). Social and ecological aspects of the water resources management of the transboundary rivers of Central Asia PARVIZ NORMATOV Tajik National University, 17 Rudaki Ave, Dushanbe, 734025, Tajikistan [email protected] Abstract The Zeravshan River is a transboundary river whose water is mainly used for irrigation of agricultural lands of the Republic of Uzbekistan. Sufficiently rich hydropower resources in upstream of the Zeravshan River characterize the Republic of Tajikistan. Continuous monitoring of water resources condition is necessary for planning the development of this area taking into account hydropower production and irrigation needs. Water quality of Zeravshan River is currently one of the main problems in the relationship between the Republics of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and it frequently triggers conflict situations between the two countries. In most cases, the problem of water quality of the Zeravshan River is related to river pollution by wastewater of the Anzob Mountain-concentrating Industrial Complex (AMCC) in Tajikistan. In this paper results of research of chemical and bacteriological composition of the Zeravshan River waters are presented. The minimum impact of AMCC on quality of water of the river was experimentally established. Key words transboundary; Central Asia; water reservoir; pollution; heavy metals; water quality INTRODUCTION Water resources in the Aral Sea Basin, whose territory belongs to five states, are mostly used for irrigation and hydropower engineering. These water users require river runoff to be regulated with different regimes. The aim of the hydropower engineering is the largest power production and, accordingly, the utilization of the major portion of annual runoff of rivers in the winter, the coldest season of the year. -

Pdf | 336.56 Kb

RAPID EMERGENCY ASSESSMENT AND COORDINATION TEAM (REACT) Floods in Khatlon: 7 – 13 May 2021 Situation Report # 1 (as of 14 May 2021) Highlights - Over 12 mudflows and landslides have been reported during the period of 7 – 13 May 2021. - Mudflows caused the death of 9 people. - Over 70 households are left homeless. - Large number of cattle has been lost and agricultural crops destroyed. - Mudflows caused disruptions to the livelihoods of around 22,000 people Situation Overview The torrential rains of 7 – 12 May 2021 triggered floods, landslides and mudflows in many of the country’s districts. The largest number of losses and destructions are faced by districts and cities of Khatlon province. Disasters affected following cities and districts: Kulob city and districts of Shamsiddini Shohin, Qushoniyon, Dangara, Yovon, Khuroson, Dusti, Vaksh, Muminobod and Jomi (please refer to Map below). CoES reports that disasters caused the death 9 people. Very preliminary estimates indicate that 74 households were left homeless and houses of another 270 households were damaged to different extent. Very modest estimations indicate damages caused by disasters to private and social infrastructure caused disruptions to the livelihoods of around 22,000 people. Government of Tajikistan activated an Inter-Agency Commission on Emergency Situations (Commission) in each disaster affected district, which fully facilitates the response operations. Furthermore, Emergency Operations Centers (Shtab) have been set up in each disaster affected district, which collects and analyzes relevant information and coordinates the response activities. Up to date, general response actions in every district include: search and rescue, evacuation of population from risk zones, constant disinfection of the affected territories, debris removal, assessment of damages and needs, registration of affected population, restoration of communal services, collection and distribution of immediate relief assistance, as well as recovery planning. -

The Economic Effects of Land Reform in Tajikistan

FAO Regional Office for Europe and Central Asia Policy Studies on Rural Transition No. 2008-1 The Economic Effects of Land Reform in Tajikistan Zvi Lerman and David Sedik October 2008 The Regional Office for Europe and Central Asia of the Food and Agriculture Organization distributes this policy study to disseminate findings of work in progress and to encourage the exchange of ideas within FAO and all others interested in development issues. This paper carries the name of the authors and should be used and cited accordingly. The findings, interpretations and conclusions are the authors’ own and should not be attributed to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, its management, or any member countries. Zvi Lerman is Sir Henry d’Avigdor Goldsmid Professor of Agricultural Economics, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel David Sedik is the Senior Agricultural Policy Officer in the FAO Regional Office for Europe and Central Asia. Contents Executive summary . 1 1. Introduction: purpose of the study. 5 2. Agriculture in Tajikistan. 7 2.1. Geography of agriculture in Tajikistan. 8 Agro-climatic zones of Tajikistan. 10 Regional structure of agriculture. 13 2.2. Agricultural transition in Tajikistan: changes in output and inputs. 15 Agricultural land. 16 Agricultural labor. 17 Livestock. 17 Farm machinery. 19 Fertilizer use. 19 3. Land reform legislation and changes in land tenure in Tajikistan. 21 3.1. Legal framework for land reform and farm reorganization. 21 3.2. Changes in farm structure and land tenure since independence. 24 4. The economic effects of land reform . 27 4.1. Recovery of agricultural production in Tajikistan. -

Annual Report

FUNDED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION IMPLEMENTED BY THE UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME With financial support from the Russian Federation ANNUAL REPORT ON IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS OF THE PROJECT “LIVELIHOOD IMPROVEMENT OF RURAL POPULATION IN 9 DISTRICTS OF THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN” FROM JANUARY 1 TO DECEMBER 31, 2017 Dushanbe 2017 1 Russian Federation-UNDP Trust Fund for Development (TFD) Project Annual Narrative and Financial Progress Report for January 1 – December 31, 2017 Project title: "Livelihood Improvement of Rural Population in 9 districts of the Republic of Tajikistan" Project ID: 00092014 Implementing partner: United Nations Development Programme, Tajikistan Project budget: Total: 6,700,000 USD TFD: Government of the Russian Federation: 6,700,000 USD Project start and end date: November 2014 – December 2017 Period covered in this report: 1st January to 31st December 2017 Date of the last Project Board 17th January 2017 meeting: SDGs supported by the project: 1, 2, 5, 8, 9, 10, 12 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Please provide a short summary of the results, highlighting one or two main achievements during the period covered by the report. Outline main challenges, risks and mitigation measures. The project "Livelihood Improvement of Rural Population in 9 districts of the Republic of Tajikistan", is funded by the Government of the Russian Federation, and implemented by UNDP Communities’ Program in the Republic of Tajikistan through its regional offices. Project target areas are Isfara, Istaravshan, Ayni, Penjikent in Sughd region; Vose and Temurmalik in Khatlon region; Rasht, Tojikobod and Lakhsh (Jirgatal) in the Districts of Republican Subordination (DRS). The main objective of the project is to ensure sustainable local economic development of the target districts of Tajikistan. -

CBD First National Report

REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FIRST NATIONAL REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION Dushanbe – 2003 1 REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FIRST NATIONAL REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION Dushanbe – 2003 3 ББК 28+28.0+45.2+41.2+40.0 Н-35 УДК 502:338:502.171(575.3) NBBC GEF First National Report on Biodiversity Conservation was elaborated by National Biodiversity and Biosafety Center (NBBC) under the guidance of CBD National Focal Point Dr. N.Safarov within the project “Tajikistan Biodiversity Strategic Action Plan”, with financial support of Global Environmental Facility (GEF) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Copyright 2003 All rights reserved 4 Author: Dr. Neimatullo Safarov, CBD National Focal Point, Head of National Biodiversity and Biosafety Center With participation of: Dr. of Agricultural Science, Scientific Productive Enterprise «Bogparvar» of Tajik Akhmedov T. Academy of Agricultural Science Ashurov A. Dr. of Biology, Institute of Botany Academy of Science Asrorov I. Dr. of Economy, professor, Institute of Economy Academy of Science Bardashev I. Dr. of Geology, Institute of Geology Academy of Science Boboradjabov B. Dr. of Biology, Tajik State Pedagogical University Dustov S. Dr. of Biology, State Ecological Inspectorate of the Ministry for Nature Protection Dr. of Biology, professor, Institute of Plants Physiology and Genetics Academy Ergashev А. of Science Dr. of Biology, corresponding member of Academy of Science, professor, Institute Gafurov A. of Zoology and Parasitology Academy of Science Gulmakhmadov D. State Land Use Committee of the Republic of Tajikistan Dr. of Biology, Tajik Research Institute of Cattle-Breeding of the Tajik Academy Irgashev T. of Agricultural Science Ismailov M. Dr. of Biology, corresponding member of Academy of Science, professor Khairullaev R. -

IMAS - 2017 MEDAL DISTRIBUTION No City School Surname Name Grade Points Place 1 Ч

IMAS - 2017 MEDAL DISTRIBUTION No City School Surname Name Grade Points Place 1 Ч. Расулов МТМУ №5 TEMUROV MUHAMMADALI 6 100 Gold 2 Dushanbe Hotam PV HASANOV MUHAMMADJON 6 98 Gold 3 Dushanbe LIP KHAFIZOV PARVIZ 6 96 Gold 4 Dushanbe Hotam PV ASOEV BEZHAN 6 96 Gold 5 Хучанд МТМУ №12 ISKHAKI SAIDNEMATKHON 6 94 Silver 6 Dushanbe Hotam PV KHUJAMOV ASADBEK 6 91 Silver 7 Dushanbe Hotam PV TADZHIBAEVA MUKADDAS 6 88 Silver 8 Хучанд Гулчини маърифат JURABOEV AKRAMKHON 5 88 Silver 9 Dushanbe Hotam PV AMONOV AHLIDDIN 6 86 Silver 10 Dushanbe IPS ZARIPOV VAFO 5 86 Silver 11 Хучанд Литсейи №1 MALLOKHUJAEV ISFANDIYOR 5 86 Silver 12 Конибодом М/Х Чураев UMAROV BEHRUZ 5 86 Silver 13 Dushanbe Hotam PV KHOTAMOV SULAYMON 6 84 Bronze 14 Кулоб м. Президента POSHOQULOV AZIMJON 6 84 Bronze 15 Бустон Гимназияи №1 MUKHAMEDOV FIRDAVS 6 84 Bronze 16 Dushanbe School №20 GULOMJANOVA TAISIA 5 81 Bronze 17 Конибодом М/Х Чураев OBIDOV MUHAMMADAMIN 5 81 Bronze 18 Dushanbe Hotam PV HAKIMJONOV MUHAMMAD 6 79 Bronze 19 Dushanbe Hotam PV ABDULLOEV SARVAR 6 76 Bronze 20 Dushanbe Lyceum №2 KHUSRAVBEKOVA RUHAFZO 6 76 Bronze 21 Dushanbe Hotam PV SHARIPOV JAHONGIR 6 76 Bronze 22 Dushanbe Hotam PV MUKHTAROV AZAMAT 5 76 Bronze 23 Истаравшан Литсейи №1 SAYFIDDINOV SHOHRON 5 76 Bronze 24 Исфара Литсейи №5 GOIBNAZOV HAMIDULLOH 5 76 Bronze 25 Dushanbe Hotam PV SAIDOVA SALTANAT 4 76 Bronze 26 Исфара Мактаби №65 SHUKUROV SHAHZOD 4 76 Bronze 27 Dushanbe Hotam PV DEHOTI FARIZ 6 69 28 Dushanbe Innovation AHMEDJONOV FARRUKH 6 69 29 Хучанд Литсейи №1 ABDURAZOKOV MUHAMMADJON 6 69 30 Хучанд Литсейи -

Usaid Family Farming Program Tajikistan

USAID FAMILY FARMING PROGRAM TAJIKISTAN ANNEX 6 TO QUARTERLY REPORT: TRAINING REPORT JANUARY-MARCH 2014 APRIL 30, 2014 This annex to annual report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the sole responsibility of DAI and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. USAID FAMILY FARMING PROGRAM ANNEX 6 TO QUARTERLY REPORT: TRAINING REPORT JANUARY- MARCH 2014 Program Title: USAID Family Farming Program for Tajikistan Sponsoring USAID Office: Economic Growth Office Chief of Party: James Campbell Contracting Officer Kerry West Contracting Officer Representative Aviva Kutnick Contract Number: EDH-I-00-05-00004, Task Order: AID-176-TO-10-00003 Award Period: September 30, 2010 through September 29, 2014 Contractor: DAI Subcontractors: Winrock International Date of Publication: April 30, 2014 Author: Ilhom Azizov, Training Coordinator The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... 2 SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... 3 TRAINING OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................3 METHODS OF -

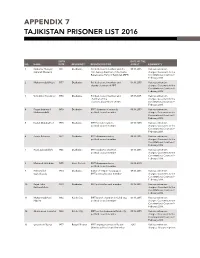

Appendix 7 Tajikistan Prisoner List 2016

APPENDIX 7 TAJIKISTAN PRISONER LIST 2016 BIRTH DATE OF THE NO. NAME DATE RESIDENCY RESPONSIBILITIES ARREST COMMENTS 1 Saidumar Huseyini 1961 Dushanbe Political council member and the 09.16.2015 Various extremism (Umarali Khusaini) first deputy chairman of the Islamic charges. Case went to the Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 2 Muhammadalii Hayit 1957 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.16.2015 Various extremism deputy chairman of IRPT charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 3 Vohidkhon Kosidinov 1956 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.17.2015 Various extremism chairman of the charges. Case went to the elections department of IRPT Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 4 Fayzmuhammad 1959 Dushanbe IRPT chairman of research, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Muhammadalii political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 5 Davlat Abdukahhori 1975 Dushanbe IRPT foreign relations, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 6 Zarafo Rahmoni 1972 Dushanbe IRPT chairman advisor, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 7 Rozik Zubaydullohi 1946 Dushanbe IRPT academic chairman, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 8 Mahmud Jaloliddini 1955 Hisor District IRPT chairman advisor, 02.10.2015 political council member 9 Hikmatulloh 1950 Dushanbe Editor of “Najot” newspaper, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Sayfullozoda IRPT political council member charges. -

Joint Forest Management (JFM)

Joint Forest Management Manual for facilitators, NGOs and projects based on Experience with implementing participatory forest management as practiced in Tajikistan between 2006 and 2015 Content Abbreviation ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Explanation of terms used ...................................................................................................................... 7 1. Background .................................................................................................................................... 9 2. Introducing Joint Forest Management to the community ............................................................... 13 2.1. Field Visit ........................................................................................................................... 14 2.2. Information Seminar ........................................................................................................... 16 2.3. Community agreement ....................................................................................................... 19 2.4. Definition and demarcation of JFM plots ............................................................................ 20 2.5. Selection of forest users ....................................................................................................... 22 2.6. JFM contract ......................................................................................................................