The Grocers' Warehouse, Castlefield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14-1676 Number One First Street

Getting to Number One First Street St Peter’s Square Metrolink Stop T Northbound trams towards Manchester city centre, T S E E K R IL T Ashton-under-Lyne, Bury, Oldham and Rochdale S M Y O R K E Southbound trams towardsL Altrincham, East Didsbury, by public transport T D L E I A E S ST R T J M R T Eccles, Wythenshawe and Manchester Airport O E S R H E L A N T L G D A A Connections may be required P L T E O N N A Y L E S L T for further information visit www.tfgm.com S N R T E BO S O W S T E P E L T R M Additional bus services to destinations Deansgate-Castle field Metrolink Stop T A E T M N I W UL E E R N S BER E E E RY C G N THE AVENUE ST N C R T REE St Mary's N T N T TO T E O S throughout Greater Manchester are A Q A R E E S T P Post RC A K C G W Piccadilly Plaza M S 188 The W C U L E A I S Eastbound trams towards Manchester city centre, G B R N E R RA C N PARKER ST P A Manchester S ZE Office Church N D O C T T NN N I E available from Piccadilly Gardens U E O A Y H P R Y E SE E N O S College R N D T S I T WH N R S C E Ashton-under-Lyne, Bury, Oldham and Rochdale Y P T EP S A STR P U K T T S PEAK EET R Portico Library S C ET E E O E S T ONLY I F Alighting A R T HARDMAN QU LINCOLN SQ N & Gallery A ST R E D EE S Mercure D R ID N C SB T D Y stop only A E E WestboundS trams SQUAREtowards Altrincham, East Didsbury, STR R M EN Premier T EET E Oxford S Road Station E Hotel N T A R I L T E R HARD T E H O T L A MAN S E S T T NationalS ExpressT and otherA coach servicesO AT S Inn A T TRE WD ALBERT R B L G ET R S S H E T E L T Worsley – Eccles – -

The Base, Manchester

Apartment 108 The Base, Worsley Street, Manchester, M15 4JP Two Bed Apartment Contact: The Base, Manchester t: 0161 710 2010 e: [email protected] or • Well-presented two bedroom apartment [email protected] • Located in the sought after Castlefield area Viewings: of Manchester City Centre Strictly by Appointment • Positioned on the first floor of the Base Landwood Group, South Central Development 11 Peter Street Manchester • Benefitting from two bathrooms, secured M2 5QR parking & balcony Date Particulars — March 2020 • Available with Vacant Possession Tenure Information The premises are held under a long leasehold title for a period of 125 years from 2003, under title number MAN60976. The annual service charge is £2045.76 per annum with the ground rent being £276.52 per annum. Tenancies Available with vacant possession. VAT All figures quoted are exclusive of VAT which may be applicable. Location Legal Each Party will be responsible for their own legal costs. The Base is located in the sought after Castlefield area of Manchester City centre. The area is extremely popular with young professionals and students due to its short Price distance from Manchester City Centre, next door to a £200,000. selection of bars and restaurants and it close proximity to the university buildings. EPC It has excellent road links into and around the city centre EPC rating D. and the Deansgate/Castlefield metrolink station is located approximately 5 minutes’ walk away. Important Notice Landwood Commercial (Manchester) Ltd for -

Wayfarer Rail Diagram 2020 (TPL Spring 2020)

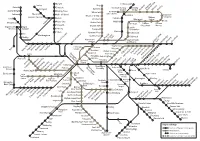

Darwen Littleborough Chorley Bury Parbold Entwistle Rochdale Railway Smithy Adlington Radcliffe Kingsway Station Bridge Newbold Milnrow Newhey Appley Bridge Bromley Cross Business Park Whitefield Rochdale Blackrod Town Centre Gathurst Hall i' th' Wood Rochdale Shaw and Besses o' th' Barn Crompton Horwich Parkway Bolton Castleton Oldham Orrell Prestwich Westwood Central Moses Gate Mills Hill Derker Pemberton Heaton Park Lostock Freehold Oldham Oldham Farnworth Bowker Vale King Street Mumps Wigan North Wigan South Western Wallgate Kearsley Crumpsall Chadderton Moston Clifton Abraham Moss Hollinwood Ince Westhoughton Queens Road Hindley Failsworth MonsallCentral Manchester Park Newton Heath Salford Crescent Salford Central Victoria and Moston Ashton-underStalybridgeMossley Greenfield -Lyne Clayton Hall Exchange Victoria Square Velopark Bryn Swinton Daisy HillHag FoldAthertonWalkdenMoorside Shudehill Etihad Campus Deansgate- Market St Holt Town Edge Lane Droylsden Eccles Castlefield AudenshawAshtonAshton Moss West Piccadilly New Islington Cemetery Road Patricroft Gardens Ashton-under-Lyne Piccadilly St Peter’s Guide Weaste Square ArdwickAshburys GortonFairfield Bridge FloweryNewton FieldGodley for HydeHattersleyBroadbottomDinting Hadfield Eccles Langworthy Cornbrook Deansgate Manchester Manchester Newton-le- Ladywell Broadway Pomona Oxford Road Belle Vue Willows HarbourAnchorage City Salford QuaysExchange Quay Piccadilly Hyde North MediaCityUK Ryder Denton Glossop Brow Earlestown Trafford Hyde Central intu Wharfside Bar Reddish Trafford North -

BRAZIL MILL, KNOTT MILL, MANCHESTER, Greater Manchester

BRAZIL MILL, KNOTT MILL, MANCHESTER, Greater Manchester Archaeological Watching Brief Oxford Archaeology North February 2007 Castlefield Estates Issue No: 2006-07/643 OA North Job No: L9798 NGR: centred SJ 383381 397472 Document Title: BRAZIL MILL, KNOTT MILL, MANCHESTER Document Type: Archaeological Watching Brief Client Name: Castlefield Estates Issue Number: 2006-07/643 OA Job Number: L9798 National Grid Reference: SJ 383381 397472 Prepared by: Ian Miller Signed……………………. Position: Project Manager Date: March 2005 Approved by: Alan Lupton Signed……………………. Position: Operations Manager Date: February 2007 Document File Location Wilm/Projects/L9798/Report Oxford Archaeology North © Oxford Archaeological Unit Ltd 2007 Storey Institute Janus House Meeting House Lane Osney Mead Lancaster Oxford LA1 1TF OX2 0EA t: (0044) 01524 848666 t: (0044) 01865 263800 f: (0044) 01524 848606 f: (0044) 01865 793496 w: www.oxfordarch.co.uk e: [email protected] Oxford Archaeological Unit Limited is a Registered Charity No: 285627 Disclaimer: This document has been prepared for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be relied upon or used for any other project without an independent check being carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Oxford Archaeology being obtained. Oxford Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than the purposes for which it was commissioned. Any person/party using or relying on the document for such other purposes agrees, and will by such use or reliance be taken to confirm their agreement to indemnify Oxford Archaeology for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. -

Social and Religious Jewish Non- Conformity: Representations of the Anglo-Jewish Experience in the Oral Testimony Archive of the Manchester Jewish Museum

SOCIAL AND RELIGIOUS JEWISH NON- CONFORMITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE ANGLO-JEWISH EXPERIENCE IN THE ORAL TESTIMONY ARCHIVE OF THE MANCHESTER JEWISH MUSEUM A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Tereza Ward School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Abbreviations.............................................................................................................. 5 Abstract ....................................................................................................................... 6 Declaration .................................................................................................................. 7 Copyright Statement .................................................................................................. 8 Acknowledgments ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 10 1.1. The aims of this study .................................................................................. 10 1.2. A Brief history of Manchester Jewry: ‘the community’.............................. 11 1.3. Defining key terms ...................................................................................... 17 1.3.1. Problems with definitions of community and their implications for conformity ......................................................................................................... -

Mapping the Geographies of Manchester's Housing Problems

Mapping the geographies of Manchester’s housing problems and the twentieth century 3 solutions Martin Dodge “Manchester is a huge overgrown village, built according to no definite plan. The factories have sprung up along the rivers Irk, Irwell and Medlock, and the Rochdale Canal. The homes of the work-people have been built in the factory districts. The interests and convenience of the manufacturers have determined the growth of the town and the manner of that growth, while the comfort, health and happiness have not been consid- ered. … Every advantage has been sacrificed to the getting of money.” Dr. Roberton, a Manchester surgeon, in evidence to the Parliamentary Committee on the Health of Towns, 1840 (quoted in Bradshaw, 1987). The industrial city and its housing mid-nineteenth century, private estates of substan- conditions tial suburban villas were constructed, away from Where people live and the material housing the poverty and pollution of the inner industrial conditions they enjoy has been a central concern neighbourhoods. An example of these early to geographers, planners and scholars in housing suburban housing developments for the elites studies and urban sociology throughout the was Victoria Park, planned in 1837; large detached twentieth century. The multifaceted challenge mansions on tree lined avenues were built in the of adequately housing an expanding population 1840s and 1850s. The goal was to provide a sense has been at the heart of the history of Manchester of seclusion and tranquillity of countryside, but and its changing geography. From the city’s rapid with proximity to the city centre and commercial industrialisation in the 1780s onwards, through activity; gated entrances to estates were installed physical growth into a metropolis with global to enforce social exclusivity. -

Manchester Urban Historic Landscape

8. Photographic images of Manchester Plate 1 Hasty Lane, Hale. Wet pasture Plate 2 Wilmslow Old Road, Hale. Vernacular cottages with airport buildings to rear 166 Plate 3 Far Lane, Gorton. Late 18 th century terraced houses Plate 4 Wythenshawe Hall, south elevation. Post medieval double cross wing hall 167 Plate 5 Hough End Hall, Chorlton-cum-Hardy. Tudor hall in incongruous modern surroundings Plate 6 Didsbury historic core and site of village green 168 Plate 7 Kelvin Street, Northern Quarter. Late 18 th century workshop dwellings Plate 8 George Leigh and Sherrat Street. 19 th century terraced houses 169 Plate 9 Fletcher Moss, Didsbury. Converted 19 th century villa Plate 10 Oblique aerial view over Hulme 170 Plate 11 Victoria Square, Oldham Road. Late 19 th century municipal housing Plate 12 Nicholas Road, Chorlton-cum-Hardy. Late 19 th to early 20 th century higher status terraced houses 171 Plate 13 Nearcroft Road Area, Wythenshawe. Early 20 th century ‘garden city’ housing Plate 14 Ryebank Road, Chorlton-cum-Hardy. Late 20 th century private housing development 172 Plate 15 New Islington, Ancoats. Post-1999 private housing development Plate 16 Edge Lane, Chorlton-cum-Hardy. Late 20 th century infill development 173 Plate 17 Heaton Park. Historic parkland Plate 18 Gorton Road (northern side), West Gorton. Industrial waste ground with surviving World War II air raid shelters 174 Plate 19 Old Mill Street, Ancoats. Views across to Ancoats mills Plate 20 Ancoats mills and Rochdale Canal 175 Plate 21 Gas holders, Bradford Road Plate 22 Chetham’s College and Library 176 Plate 23 Church of St Francis, Gorton Lane, Gorton. -

Manchester Geographies

Manchester Geographies This collection of essays has been produced to mark Paul Hindle’s 30 years of service to the Manchester Geographical Society. Paul became a member of the Society’s Council in 1983. He was appointed Acting Honorary Secretary in 1986 and Honorary Secretary in 1987. For many years, Paul has taken an interest in the Society’s history, and he has written about the two most recent phases (1973-1997 and 1998-2010) in the Society’s journals. He was editor of the printed journal The North West Geographer from 1981 to 1986, and has edited the on-line journal North West Geography since 2001. Paul’s work as Honorary Secretary did much to ensure the smooth Geographical Society’s open lecture series, transition of the Society to a Charitable Trust Paul continues to provide great service, not in 2010. He is one of the Society’s ten Trustees least in operating the Society’s Registered and a member of the Academic Committee Office. Beyond the Society, Paul is connected that, as part of its work, oversees Research to two other charities, as Chairman of the Grant and Postgraduate Awards. A regular Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal Society and (and admired) contributor to the Manchester a committee member of Bolton Choral Union. References Hindle B P (1998) Turmoil and Transition: the Manchester Geographical Society, 1973-1997. The North West Geographer 2/1 11–21. Hindle B P (2010) Continuing Change: Manchester Geographical Society, 1998-2010. North West Geography 10/2 19–22. Manchester Geographies i ii Manchester Geographies Manchester Geographies Edited by Wilfred Theakstone GRA EO P G H IC R A E L T Manchester S S E O H C C I E N Geographical T A Y M Society 2017 Manchester Geographies iii Acknowledgements Her Majesty The Queen is the Patron of the Manchester Geographical Society. -

Chapter 4 URBAN REGENERATION CITY of MANCHESTER

Chapter 4 URBAN REGENERATION CITY OF MANCHESTER Table of Contents 4.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 4 4.2 Brief History of Manchester: City Profile ........................................................ 4 4.2.1 Post-Industrial Shift ............................................................................................... 4 4.2.2 Greater Manchester Regional Structure................................................................. 5 4.2.3 Creating a Centre: Ongoing Management of Growth in the Manchester Core ..... 5 4.3 Castlefield ................................................................................................................. 7 4.3.1 Background............................................................................................................ 7 4.3.2 Decline of the 1950's and 1960's............................................................................ 8 4.3.3 Regeneration - Urban Heritage Park...................................................................... 8 4.3.4 Key Projects of the Regeneration Programme - Results........................................ 8 4.3.4.1 Redevelopment of the Middle Warehouse (Castle Quay) ......................................................... 8 4.3.4.2 Slate Wharf ................................................................................................................................9 4.3.4.3 Merchants' Warehouse............................................................................................................. -

Infra Mancrichard Brook + Martin Dodge PICC-VIC TUNNEL

Futurebound Services HELIPORT MANCUNIAN WAY Infra_MANCRichard Brook + Martin Dodge PICC-VIC TUNNEL GUARDIAN EXCHANGE Catalogue to accompany the exhibition CUBE Gallery | RIBA Hub Spring 2012 Infra_MANC Infra_MANC Post-war infrastructures of Manchester The catalogue of Infra_MANC. An exhibition at the RIBA Hub / CUBE Gallery, Portland Street Manchester from 27th February – 17th March 2012. Curated by Richard Brook and Martin Dodge Richard Brook Manchester School of Architecture, John Dalton West, Chester Street, Manchester. M1 5GD, UK. Martin Dodge Department of Geography, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PL, UK. Infra_MANC Prelims Second edition 2012 © Richard Brook and Martin Dodge 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Richard Brook and Martin Dodge have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the authors and editors of this work. Published by bauprint 34 Milton Road Prestwich Manchester M25 1PT ISBN 978-0-9562913-2-5 Prelims Infra_MANC Table of contents Acknowledgements Curator biographies Introduction and overview map Timeline Ch.001 Helicopter Dreaming Ch.002 Mancunian Way [A57(M)] Our Highway in the Sky Ch.003 The Picc-Vic Tunnel Ch.004 Guardian Underground Telephone Exchange Bibliography List of exhibits Exhibition photos Infra_MANC Prelims ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Copyright The exhibition and catalogue are an academic project and were undertaken on a non-commercial basis. We have assembled visual materials from a large number of sources and have endeavoured to secure suitable permissions. -

The Freight Solution to the Castlefield Problem

The Freight Solution to the Castlefield Problem Including The Business Case for a new route and western access to Trafford Park April 2020 (Revised August 2020) Contents Part 1. The Castlefield Problem – Freight’s Great Opportunity .................................................................................... 2 The Problem ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 A more fundamental question ................................................................................................................................... 5 Carrington Park .......................................................................................................................................................... 6 The search for a route to the south ........................................................................................................................... 7 Connecting to the West Coast Main Line .................................................................................................................. 9 Benefits of the proposed interventions ................................................................................................................... 14 Part 2. The Business Case for a Western Route to Trafford Park ................................................................................ 15 Assumptions ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Originally a Roman Settlement, Castlefield Was Arguably the Birth-Place of Manchester

cube CUBE CENTRE FOR THE UNDERSTANDING OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT CITY TOURS: CASTLEFIELD Originally a Roman settlement, Castlefield was arguably the birth-place of Manchester. Around the mid-nineteenth century it witnessed the largest growth in its history, largely due to the industrial revolution. The rivers Medlock and Irwell were integral to its development, allowing goods to be brought in from the port of Liverpool and stored in warehouses in the basin. In 1877 the Cheshire Lines Company erected the massive Southern Iron Viaduct, still a prominent feature of the area. The combination of railway viaducts and canals has forged a distinct identity for the basin, now taken forward by new developments and refurbishments. Knott Mill abuts the area and is home to many of Manchester's leading architectural and design practices. THE BUILDINGS HAMPS ST 1 01 Granada Television 2 3 A56 02 Liverpool Road Station 03 Museum of Science and Industry LIVERPOOL RD LOWER BYROM ST 4 04 Castlefield Arena GREAT BRIDGEWAT. ST 05 Castlefield Viaduct 5 06 Dukes 92 WATER ST POTATO WHARF 07 Eastgate Office DUKE ST CASTLE ST 08 Castlefield Footbridge 6 8 10 09 Planet 4 Studios 7 13 10 Castlefield Gallery 9 11 Choice Restaurant and Bar 11 12 DEANSGATE 12 Merchants Warehouse STATION 13 Merchants Bridge MED ST 14 14 Box Works 15 GREAT 16 CHESTER RD 15 Timber Wharf JACKSON ST 16 Britannia Mills MANCUNIAN WAY 17 17 St Georges Church 01 www.cube.org.uk cube CUBE CENTRE FOR THE UNDERSTANDING OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT CITY TOURS: CASTLEFIELD: 01 GRANADA TELEVISION Quay Street, 1962 In contrast to the structural expressiveness of the architects earlier Dome of Discovery at the Festival of Britain, this is a restrained work.