Integration Policies, Practices and Experiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Schadstoff-Sammlung 2021 (Fahrplan)

Mobile Schadstoff-Sammlung 2021 (Fahrplan) Frühjahr Herbst Ort Straße / Platz Uhrzeit 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Neuenkirchen Schützenplatz 10:15-11:45 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Brochdorf Parkplatz Schützenhaus 12:00-12:15 Gefahrstoffsymbole 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Schwalingen vor ehem. Gasthaus von Fintel 12:30-13:00 Es handelt sich um Zeichen, 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Sprengel Nähe Landgasthaus zur Sprengeler Mühle 14:00-14:15 die auf gefährliche Inhalts- 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Schülern Sportplatz, Alter Schulweg 14:30-14:45 stoffe hinweisen. Diese 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Hemsen/Langeloh Kleinsporthalle Hemsen, Hemsener Weg 15:00-15:15 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Wolterdingen Friedhof 15:45-16:30 zum Beispiel auf den 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Soltau, Friedrichseck Freizeitverein Friedrichseck 16:45-17:15 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Harber Feuerwehrgerätehaus 17:30-18:00 Behältern von Farben, Frühjahr Herbst Ort Straße / Platz Uhrzeit Lacken und Lösungsmitteln. 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Wietzendorf Kampstraße, LBAG 10:15-11:30 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Reiningen Gasthaus Brammer 11:45-12:00 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Trauen Pommernweg Ecke Soldiner Str. 12:45-13:15 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Oerrel Feuerwehrgerätehaus 13:30-14:00 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Breloh Feuerwehrgerätehaus 14:30-15:15 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Munster Parkpl. Grundschule Hanloh, Alvermanns Grund 15:30-17:30 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Ilster/Alvern/Töpingen Parkplatz Heidkrug, an der B 71 17:45-18:00 umweltgefährlich Frühjahr Herbst Ort Straße / Platz Uhrzeit 28.04.2021 03.11.2021 Wintermoor Kreuzung Am Sportplatz / Vor den -

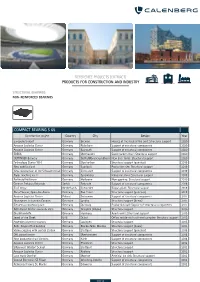

Reference List Construction and Industry

REFERENCE PROJECTS (EXTRACT) PRODUCTS FOR CONSTRUCTION AND INDUSTRY STRUCTURAL BEARINGS NON-REINFORCED BEARINGS COMPACT BEARING S 65 Construction project Country City Design Year Europahafenkopf Germany Bremen Houses at the head of the port: Structural support 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Paderborn Support of structural components 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Bayreuth Support of structural components 2020 EDEKA Germany Oberhausen Supermarket chain: Structural support 2020 OETTINGER Brewery Germany Gotha/Mönchengladbach New beer tanks: Structural support 2020 Technology Center YG-1 Germany Oberkochen Structural support (punctual) 2019 New nobilia plant Germany Saarlouis Production site: Structural support 2019 New construction of the Schwaketenbad Germany Constance Support of structural components 2019 Paper machine no. 2 Germany Spremberg Industrial plant: Structural support 2019 Parkhotel Heilbronn Germany Heilbronn New opening: Structural support 2019 German Embassy Belgrade Serbia Belgrade Support of structural components 2018 Bio Energy Netherlands Coevorden Biogas plant: Structural support 2018 NaturTheater, Open-Air-Arena Germany Bad Elster Structural support (punctual) 2018 Amazon Logistics Center Poland Sosnowiec Support of structural components 2017 Novozymes Innovation Campus Denmark Lyngby Structural support (linear) 2017 Siemens compressor plant Germany Duisburg Production hall: Support of structural components 2017 DAV Alpine Centre swoboda alpin Germany Kempten (Allgäu) Structural support 2016 Glasbläserhöfe -

Hannover Hbf – Soltau (Han) – Hamburg-Harburg RB38

Hamburg Buxtehude Cuxhaven HarHarr RB38 Winsen (Luhe) Lüneburg Bchhol Nordheide Uelzen Bremen Suerhop Holm-Seppensen Büsenbachtal Handeloh RB38 Wintermoor HVV - Hamburger Verkehrsverbund Hannover Hbf – Soltau (Han) – Hamburg-Harburg Schneverdingen RB38 Wolterdingen (Han) Hamburg Buxtehude Soltau Nord Hamburg-Harburg Cuxhaven RB38 HarHarr Bus von Soltau Sola Han nach Bispingen RB38 Dorfmark Buchholz (Nordheide) Winsen (Luhe) Suerhop Lüneburg Bchhol Nordheide Uelzen Tarifausweitung des HVV ab 15.12.2019: Holm-Seppensen Walsrode Bad Fallingbostel Bremen Der HVV wird größer und gilt künftig bis Uelzen, Büsenbachtal Suerhop Soltau und Cuxhaven. Handeloh Holm-Seppensen Hodenhagen Dadurch verändern sich die Zonen und Ringe RB38 Büsenbachtal NEU HVV-Einzel-, Wintermoor Handeloh RB38 auf der Strecke der RB38 an den Bahnhöfen Tages- und Zeit- Wolterdingen, Soltau Nord und Soltau (Han). karten Ring E Schneverdingen RB38 Wintermoor NEU HVV-Einzel-, Wolterdingen (Han) Schwarmstedt • Verschiebung von Ring E nach F Tages- und Zeit- Schneverdingen karten Ring F Soltau Nord • Veränderung der Zonen-Nummern: Wolter- Lindwedel dingen, Soltau Nord und Soltau (Han) 838 -> Wolterdingen (Han) RB38 Soltau (Han) NEU HVV-Einzel-, Mellendorf 1028 Dorfmark Tages- und Zeit- Soltau Nord karten Ring F Bitte lassen Sie Ihre Zeitkarte ggf. in einer der Bus von Soltau Walsrode Bad Fallingbostel Hannover Sola Han nach Bispingen RB38 Servicestellen oder Ihr ProfiTicket bei Ihrem Dorfmark Flughafen Arbeitgeber ändern. Weitere Informationen un- Tarifinfos:Hodenhagen anenhaen -

VERMILION VOR ORT 000 000 00 Fachinformation 00 60 60 00 0 000 50 50 59 59

0 3300000 3350000 3400000 3450000 3500000 3550000 3600000 3650000 3700000 3750000 3800000 3850000 3900000 3950000 00 000 00 00 61 61 000 50 60 6050000 VERMILION VOR ORT 000 000 00 Fachinformation 00 60 60 0 00 000 50 50 59 59 Information zum Vorhaben Erdgaserkundung im Raum Bad Fallingbostel 0 000 Region Heidekreis 00 590000 59 Energieregion Niedersachsen: Heimisches Erdgas für eine zuverlässige Versorgung 0 0 00 50 Niedersachsen spielt bei der Deckung des Gasbedarfs in Deutschland eine zen- 585000 58 trale Rolle: Über 95 % des bundesweit produzierten Erdgases stammen aus Nieder- 0 sachsen. Damit trägt das Land ganz wesentlich zur sicheren Energieversorgung in 0 00 00 Deutschland und der Region bei. Abb. 1 zeigt die bekannten Erdgas- und Erdöllager580000 - 58 stätten in Niedersachsen. 0 0 00 50 Erdgasförderung in der Region Heidekreis 575000 57 Abb. 1 Erdgas- und Erdölfelder in Niedersachsen 0 In der Region Heidekreis wird bereits seit mehr als 50 Jahren Erdgas gefördert und Staatsgrenze Erdgaslagerstätten 0 00 00 sie verfügt noch heute über reiche Erdgasvorkommen. Seit Beginn der ersten Bohr-570000 Niedersachsen Erdöllagerstätten 57 aktivitäten im Jahr 1906 wurden im Landkreis 456 Bohrungen abgeteuft, davon 99 3300000 3350000 3400000 3450000 3500000 3550000 3600000 3650000 3700000 3750000 3800000 3850000 3900000 3950000 Allgemein Kohlenwasserstoff Felder 0840 0 Ablenkungen Untertage, die man Obertage nicht sieht. Etwa 300 dieser Bohrungen Kilometer Staatsgrenze Gas KohlenwasserstoffBommelsen Z1 Felder Niedersachen NÖl sind Erdölbohrungen, die übrigen Erdgasbohrungen. Größere Funde reichen von Bundesländer Visselhövedein Norddeutschland dem Erdölfeld Hansa im Jahr 1942 bis zum Erdgasfeld Idsingen im Jahr 1996. Weite- Soltau Date: 2017/03/16 Edited by: P.-F. -

Metropolregion Hannover – Braunschweig – Göttingen – Wolfsburg

Metropolregion Hannover – Braunschweig – Göttingen – Wolfsburg Ausgewählte erste Ergebnisse des Zensus vom 9. Mai 2011 Metropolregion Hannover – Braunschweig – Göttingen – Wolfsburg Ausgewählte erste Ergebnisse des Zensus vom 9. Mai 2011 Impressum Metropolregion Hannover – Braunschweig – Göttingen – Wolfsburg Ausgewählte erste Ergebnisse des Zensus vom 9. Mai 2011 ISSN 2197-6295 Herausgeber: Statistisches Landesamt Bremen Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein Statistisches Amt Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Landesamt für Statistik Niedersachsen Herstellung und Redaktion: Landesamt für Statistik Niedersachsen (LSN) Postfach 91 07 64 30427 Hannover Telefon: 0511 9898-0 Fax: 0511 9898-4132 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.statistik.niedersachsen.de Auskünfte: Landesamt für Statistik Niedersachsen Telefon: 0511 9898 - 1132 0511 9898 - 1134 Fax: 0511 9898 - 4132 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.statistik.niedersachsen.de Download als PDF unter: http://www.statistik.niedersachsen.de/portal/live.php?navigation_id=25706&article_id=118375&_psmand=40 Zu den norddeutschen Metropolregionen erscheinen folgende vergleichbare Broschüren: Metropolregion Hamburg. Ausgewählte erste Ergebnisse des Zensus vom 9. Mai 2011 Metropolregion Bremen-Oldenburg. Ausgewählte erste Ergebnisse des Zensus vom 9. Mai 2011 Titelbilder: Oben rechts: Fotograf: Zeppelin, Some rights reserved. Quelle: www.piqs.de Oben links: Fotograf: Ilagam, Some rights reserved. Quelle: www.piqs.de Unten rechts: Fotograf: Daniel Schwen, -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of December, 2009 Club Fam

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of December, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 111NH 21484 ALFELD 0 0 0 35 35 District 111NH 21485 BAD PYRMONT 0 0 0 42 42 District 111NH 21486 BRAUNSCHWEIG 0 0 0 52 52 District 111NH 21487 BRAUNSCHWEIG ALTE WIEK 0 0 0 52 52 District 111NH 21493 BURGDORF-ISERNHAGEN 0 0 0 33 33 District 111NH 21494 CELLE 0 0 0 43 43 District 111NH 21497 EINBECK 0 0 0 35 35 District 111NH 21501 GIFHORN 0 0 0 33 33 District 111NH 21502 GOETTINGEN 0 0 0 45 45 District 111NH 21505 HAMELN 0 0 0 41 41 District 111NH 21506 HANNOVER CALENBERG 0 0 0 30 30 District 111NH 21507 HANNOVER 0 0 0 59 59 District 111NH 21508 HANNOVER HERRENHAUSEN 0 0 0 51 51 District 111NH 21509 HANNOVER TIERGARTEN 0 0 0 38 38 District 111NH 21510 HELMSTEDT 0 0 0 41 41 District 111NH 21511 HILDESHEIM 0 0 2 43 45 District 111NH 21512 HILDESHEIM MARIENBURG 0 0 0 39 39 District 111NH 21513 HILDESHEIM ROSE 0 0 0 50 50 District 111NH 21514 HOLZMINDEN 0 0 0 39 39 District 111NH 21518 MUNSTER OERTZE 0 0 0 36 36 District 111NH 21521 GOSLAR-BAD HARZBURG 0 0 0 44 44 District 111NH 21522 NORTHEIM 0 0 0 35 35 District 111NH 21523 OBERHARZ 0 0 0 32 32 District 111NH 21528 SUEDHARZ 0 0 0 34 34 District 111NH 21531 PEINE 0 0 0 44 44 District 111NH 21532 PORTA WESTFALICA 0 0 0 35 35 District 111NH 21534 STEINHUDER MEER 0 0 0 28 28 District 111NH 21535 UELZEN 0 0 0 40 40 District 111NH 21536 USLAR 0 0 0 31 31 District 111NH 21539 WITTINGEN 0 0 0 33 33 District 111NH -

Gesamtehrungsliste Stand 07.2019

Verleihung der Goldenen, Silbernen und Bronzenen Ehrennadel des LSB Niedersachsen im Juli 2019: GOLD: Dirks, Johann Schützenverein Wiesede von 1875 KSB Wittmund Köln, Reinhard Fachverband Schießsport Isernhagen RSB Hannover Nussbaum, Wilhelm Fußballverband NFV Kreis Nienburg KSB Nienburg SILBER: Aue, Dirk MTV v. 1896 Harsum KSB Hildesheim Bettscheider, Ingo MTV v. 1896 Harsum KSB Hildesheim Brinkmann, Lutz FC Hevesen-Schaumburg KSB Schaumburg Brinkmann, Ute FC Hevesen-Schaumburg KSB Schaumburg Donat, Wolfram TTC Behringen Sportbund Heidekreis Harting, Jörg FC Hevesen-Schaumburg KSB Schaumburg Harting, Ralf FC Hevesen-Schaumburg KSB Schaumburg Lange, Annegret TTC Behringen Sportbund Heidekreis Luge, Stefan MTV v. 1896 Harsum KSB Hildesheim Meyer, Manfred TTC Behringen Sportbund Heidekreis Neugebauer, Dirk MTV v. 1896 Harsum KSB Hildesheim BRONZE: Kaufhold, Dr., Stephan MTV v. 1896 Harsum KSB Hildesheim Möller, Karl MTV v. 1896 Harsum KSB Hildesheim Rollwage, Dirk MTV v. 1896 Harsum KSB Hildesheim Verleihung der Goldenen, Silbernen und Bronzenen Ehrennadel des LSB Niedersachsen im Juni 2019: GOLD: Bollow, Werner NFV Kreis Diepholz KSB Diepholz Buck, Herbert TSV Hönau-Lindorf KSB Rotenburg Einhaus, Franz KSB Peine (Landrat des LK Peine) KSB Peine Geers, Hans SV DJK Eintracht Börger KSB Emsland Hartmann, Frank TUSPO Billingshausen KSB Göttingen- Osterode Heitmann, Mark TV Neuenkirchen KSB Diepholz Heynold, Hans-Bernhard Bürgerschützengesellschaft v. 1252 KSB Northeim-Einbeck Northeim Kompa, Peter SV Harderberg KSB Osnabrück-Land Mey, Gerhard -

The Spatial and Temporal Diffusion of Agricultural Land Prices

The Spatial and Temporal Diffusion of Agricultural Land Prices M. Ritter; X. Yang; M. Odening Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Department of Agricultural Economics, Germany Corresponding author email: [email protected] Abstract: In the last decade, many parts of the world experienced severe increases in agricultural land prices. This price surge, however, did not take place evenly in space and time. To better understand the spatial and temporal behavior of land prices, we employ a price diffusion model that combines features of market integration models and spatial econometric models. An application of this model to farmland prices in Germany shows that prices on a county-level are cointegrated. Apart from convergence towards a long- run equilibrium, we find that price transmission also proceeds through short-term adjustments caused by neighboring regions. Acknowledegment: Financial support from the China Scholarship Council (CSC NO.201406990006) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through Research Unit 2569 “Agricultural Land Markets – Efficiency and Regulation” is gratefully acknowledged. The authors also thank Oberer Gutachterausschuss für Grundstückswerte in Niedersachsen (P. Ache) for providing the data used in the analysis. JEL Codes: Q11, C23 #117 The Spatial and Temporal Diffusion of Agricultural Land Prices Abstract In the last decade, many parts of the world experienced severe increases in agricultural land prices. This price surge, however, did not take place evenly in space and time. To better understand the spatial and temporal behavior of land prices, we employ a price diffusion model that combines features of market integration models and spatial econometric models. An application of this model to farmland prices in Germany shows that prices on a county-level are cointegrated. -

Jugendherberge Bad Fallingbostel Bad Fallingbostel Per Bahn: Mit Der Bahn Erreichen Sie Den Bahnhof in Liethweg 1 Auf Zu Löns Und Löwen! Bad Fallingbostel

051.15.1404_HP_Fallingbostel_051.15._HP_BadFallingbostel 29.10.15 17:22 Seite 2 Willkommen in NIEDERSACHSEN Lüneburg Workshop, Tagung, Entspannung! Mitglied werden, Werte fördern! Hitzacker Für Tagungen halten wir Overheadprojektor, Leinwand, Jugendherbergen stehen allen offen – Menschen jeden Alters, Bispingen Beamer, Flipchart, Pinnwand, Fernsehgerät, DVD-Player und jeder ethnischen Herkunft und Weltanschauung, sind herzlich Uelzen einen Moderationskoffer bereit. Im großen Mehrzweckraum willkommen. Voraussetzung ist lediglich eine gültige DJH- Bad Fallingbostel Müden steht ein Klavier bereit, zur Abend- Mitgliedskarte bzw. DJH-Gruppenkarte. Mitglied werden Sie in oder Abschlussdisco kommt allen DJH-Geschäftsstellen und Jugendherbergen. So stehen Hankensbüttel unsere Musikanlage zum Ihnen nicht nur die deutschen Jugendherbergen und Youth Einsatz. Hostels weltweit offen, Sie unterstützen auch die völkerver- Celle bindende Idee des DJH. Mardorf Das große Außengelände lädt ein zu Spaß und Hannover Wolfsburg Weitere Informationen bekommen Sie unter: Spiel mit Tischtennis, www.djh-niedersachsen.de · Telefon 0511 16402-37 Braunschweig Beachvolleyballfeld und Hildesheim schönem Spielplatz. Fahr- Hameln Schöningen zeuge, Spielgeräte und Bodenwerder Sandspielzeug können gern Goslar entliehen werden. Hahnenklee Torfhaus Silberborn Braunlage Gute Reise, guten Appetit! Bad Sachsa Nach erholsamer Nacht mundet das reichhaltige Frühstücks- Göttingen büffet vorzüglich. Bei Halb- und Vollpension sind die Büffets Hann. Münden ebenfalls abwechslungsreich -

Members and Sponsors

LOWER SAXONY NETWORK OF RENEWABLE RESOURCES MEMBERS AND SPONSORS The 3N registered association is a centre of expertise which has the objective of strengthening the various interest groups and stakeholders in Lower Saxony involved in the material and energetic uses of renewable resources and the bioeconomy, and supporting the transfer of knowledge and the move towards a sustainable economy. A number of innovative companies, communities and institutions are members and supporters of the 3N association and are involved in activities such as the production of raw materials, trading, processing, plant technology and the manufacturing of end products, as well as in the provision of advice, training and qualification courses. The members represent the diversity of the sustainable value creation chains in the non-food sector in Lower Saxony. 3 FOUNDING MEMBER The Lower Saxony Ministry for Food, Agriculture and Con- Contact details: sumer Protection exists since the founding of the state of Niedersächsches Ministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Verbraucherschutz Lower Saxony in 1946. Calenberger Str. 2 | 30169 Hannover The competences of the ministry are organized in four de- Contact: partments with the following emphases: Ref. 105.1 Nachwachsende Rohstoffe und Bioenergie Dept 1: Agriculture, EU farm policy (CAP), agricultural Dr. Gerd Höher | Theo Lührs environmental policy Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Dept 2: Consumer protection, animal health, animal Further information: www.ml.niedersachsen.de protection Dept 3: Spatial planning, regional development, support Dept 4: Administration, law, forests Activities falling under the general responsibility of the ministry are implemented by specific authorities as ‘direct’ state administration. -

Freizeit-Tipps Zum Dahin- Schmelzen

2020 07 JG 11 / DAS FREIZEIT- UND EVENTMAGAZIN FÜR DIE HEID EREGION AUSFLUGSZIELE IN DER HEIDEREGION FREIZEIT-TIPPS ZUM DAHIN- SCHMELZEN SCHLUSS MIT LANGEWEILE BEI DIESEN 20 TIPPS WERDEN ALLE FÜNDIG HEIDEREGION FREIZEITPARKS AN JEDER ECKE ATTRAKTIONEN ETWAS LOS! Sonntag, 27. September 2020 Stadthalle Walsrode 20:00 Uhr Veranstalter: TriBuehne e.V. WILLKOMMEN Frau Kaminski Am Risch 26 BEI DEN 29683 Bad Fallingbostel Telefon 01522 9462061 HARTMANNS Mail: [email protected] Komödie von Simon Verhoeven Vorverkaufsstellen: Bildrechte: © Bernd Boehner ➤ Ticketcenter Walsroder Zeitung ➤ Tourist-Information Vogelpark-Region in Walsrode Sonntag, 29. November 2020 und Bad Fallingbostel Stadthalle Walsrode 20:00 Uhr SCHTONK! Bühnenstück nach dem Film von Helmut Dietl Plakat: © Gio Loewe Bildrechte: © Dennis Satin Bildrechte: © Matthias Stutte Samstag, 12. Dezember 2020 Stadthalle Walsrode 20:00 Uhr HEILIG ABEND Thriller von Daniel Kehlmann Bildrechte: © Joachim Hiltmann Sonntag, 17. Januar 2021 Stadthalle Walsrode 20:00 Uhr HEXENJAGD Schauspiel von Arthur Miller Bildrechte: © Dietrich Dettmann Spielplan Sonntag, 7. März 2021 Stadthalle Walsrode 2020 20:00 Uhr & EXTRAWURST Bildrechte: © Joachim Hiltmann 2021 Dramödie von Dietmar Jacobs und Moritz Netenjakob mit Gerd Silberbauer Extrawurst Plakatmotiv © Konzertdirektion Landgraf EDITORIAL Sonntag, 27. September 2020 Stadthalle Walsrode 20:00 Uhr Veranstalter: TriBuehne e.V. WILLKOMMEN Frau Kaminski Am Risch 26 BEI DEN 29683 Bad Fallingbostel Telefon 01522 9462061 HARTMANNS Mail: [email protected] -

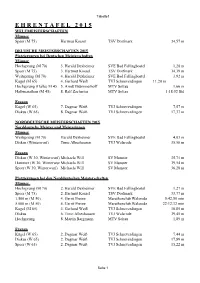

E H R E N T a F E L 2 0

Tabelle1 E H R E N T A F E L 2 0 1 5 WELTMEISTERSCHAFTEN Männer Speer (M 75) Hartmut Kossel TSV Dorfmark 34,57 m DEUTSCHE MEISTERSCHAFTEN 2015 Platzierungen bei Deutschen Meisterschaften Männer Hochsprung (M 70) 3. Harald Dexheimer SVE Bad Fallingbostel 1,28 m Speer (M 75) 3. Hartmut Kossel TSV Dorfmark 34,39 m Weitsprung (M 70) 4. Harald Dexheimer SVE Bad Fallingbostel 3,92 m Kugel (M 65) 4. Gerhard Weiß TVJ Schneverdingen 11,20 m Hochsprung (Halle) M 45 5. Arndt Brümmerhoff MTV Soltau 1,66 m Halbmarathon (M 45) 8. Ralf Zacharias MTV Soltau 1:18:52 Std Frauen Kugel (W 65) 7. Dagmar Weiß TVJ Schneverdingen 7,57 m Diskus (W 65) 8. Dagmar Weiß TVJ Schneverdingen 17,37 m NORDDEUTSCHE MEISTERSCHAFTEN 2015 Norddeutsche Meister und Meisterinnen Männer Weitsprung (M 70) Harald Dexheimer SVE Bad Fallingbostel 4,03 m Diskus (Winterwurf) Timo Albeshausen TVJ Walsrode 35,56 m Frauen Diskus (W 30, Winterwurf) Michaela Will SV Munster 35,71 m Hammer (W 30, Winterwurf)Michaela Will SV Munster 39,54 m Speer (W 30, Winterwurf) Michaela Will SV Munster 36,28 m Platzierungen bei den Norddeutschen Meisterschaften Männer Hochsprung (M 70) 2. Harald Dexheimer SVE Bad Fallingbostel 1,27 m Speer (M 75) 2. Hartmut Kossel TSV Dorfmark 33,77 m 1.500 m (M 50) 4. Gerrit Preine Marathonclub Walsrode 5:42,50 min 5.000 m (M 50) 4. Gerrit Preine Marathonclub Walsrode 22:12,32 min Kugel (M 65) 4. Gerhard Weiß TVJ Schneverdingen 10,85 m Diskus 6.