THE SILENT WORLD of DOCTOR and PATIENT" Alexander M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VORTEX Playing Mrs Constance Clarke

THE BIG FINISH MAGAZINE MARCH 2021 MARCH ISSUE 145 DOCTOR WHO: DALEK UNIVERSE THE TENTH DOCTOR IS BACK IN A BRAND NEW SERIES OF ADVENTURES… ALSO INSIDE TARA-RA BOOM-DE-AY! WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH THEBIGFINISH @BIGFINISHPROD BIGFINISHPROD BIG-FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULL-CAST AUDIO DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND/OR DOWNLOAD WE LOVE STORIES Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers, The Prisoner, The Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain Scarlet, Space: 1999 and Survivors, as well as classics such as HG Wells, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray. We also produce original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield, plus the THE BIG FINISH APP Big Finish Originals range featuring seven great new series: The majority of Big Finish releases ATA Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence can be accessed on-the-go via Investigate, Blind Terror, Transference and The Human Frontier. the Big Finish App, available for both Apple and Android devices. Secure online ordering and details of all our products can be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF EDITORIAL SINCE DOCTOR Who returned to our screens we’ve met many new companions, joining the rollercoaster ride that is life in the TARDIS. We all have our favourites but THE SIXTH DOCTOR ADVENTURES I’ve always been a huge fan of Rory Williams. He’s the most down-to-earth person we’ve met – a nurse in his day job – who gets dragged into the Doctor’s world THE ELEVEN through his relationship with Amelia Pond. -

The Right to Remain Silent: Abortion and Compelled Physician Speech

Boston College Law Review Volume 62 Issue 6 Article 8 6-29-2021 The Right to Remain Silent: Abortion and Compelled Physician Speech J. Aidan Lang Boston College Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Health Law and Policy Commons, Litigation Commons, and the Medical Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation J. A. Lang, The Right to Remain Silent: Abortion and Compelled Physician Speech, 62 B.C. L. Rev. 2091 (2021), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol62/iss6/8 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RIGHT TO REMAIN SILENT: ABORTION AND COMPELLED PHYSICIAN SPEECH Abstract: Across the country, courts have confronted the question of whether laws requiring physicians to display ultrasound images of fetuses and describe the human features violate the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. On April 5, 2019, in EMW Women’s Surgical Center, P.S.C. v. Beshear, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit joined the Fifth Circuit and upheld Ken- tucky’s law, thus rejecting a physician’s free speech challenge. The Supreme Court declined to review this decision without providing an explanation. The Sixth Circuit became the third federal appellate court to rule on such regulations, often referred to as “ultrasound narration laws” or “display and describe laws,” and joined the Fifth Circuit in upholding such a law against a First Amendment challenge. -

Doctor Who: Auton Invasion

In this, the first adventure of his third 'incarnation', DOCTOR WHO, Liz Shaw and the Brigadier grapple with the nightmarish invasion of the AUTONS - living, giant-sized, plastic-modelled 'humans' with no hair and sightless eyes; waxwork replicas and tailors' dummies whose murderous behaviour is directed by the NESTENE CONSCIOUSNESS - a malignant, squid-like monster of cosmic proportions and indescribably hideous appearance. ISBN 0 426 11295 4 DOCTOR WHO AND THE AUTON INVASION Based on the BBC television serial Doctor Who and the Spearhead from Space by Robert Holmes by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation TERRANCE DICKS published by The Paperback Division of W. H. Allen & Co. Ltd CONTENTS 1 Prologue: Exiled to Earth 2 The Mystery of the Meteorites 3 The Man from Space 4 The Faceless Kidnappers 5 The Hunting Auton 6 The Doctor Disappears 7 The Horror in the Factory 8 The Auton Attacks 9 The Creatures in the Waxworks 10 The Final Battle A Target Book Published in 1974 by the Paperback Division of W. H. Allen & Co. Ltd. A Howard & Wyndham Company 44 Hill Street, London W1X 8LB Novelisation copyright © Terrance Dicks Original script copyright © Robert Holmes 1970 W. H. Allen & Co. Ltd illustrations copyright © 1974 'Doctor Who' series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1970, 1974 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Anchor Brendon Ltd, Tiptree, Essex ISBN 0426 10313 0 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Jumpchain CYOA Version 1.0 by Blackshadow111

Jumpchain CYOA Version 1.0 By blackshadow111 Introduction Welcome, Jumper, to a world without peer. Time travel, space travel, reality travel...basically every travel not only exists here, but is rather common and achievable! A world with Time Lords, hate-filled salt shakers, sapient stars and much, much more! This is a world full of tremendous wonders, of bright and glorious things, beautiful sights and unimaginable delights! Step in, go around, see the sights and have fun! It is also full of hideous horror, unfortunate implications, wars and conflicts that can rip apart entire galaxies and time-spans, memetic horrors and nightmares. Step carefully, lest someone else end up treating you as their fun. Either way, you will need these 1 000 CP. Go on, shoot your own series! Time and Place Being honest, neither time nor place mean all that much here. So we’ll be doing this a tad differently. Start out wherever and whenever you like that isn’t a fixed point in time or otherwise a part of the Time War. Now spend a total of ten years of your own personal duration in this universe, regardless of whatever era those years may be lived in. Age and Gender You may choose your age and gender freely, within the limitations of whatever your species is. This show has had adventure opportunities for everyone from children to octagenarians, and that’s just the humans. Origins Madman: Without a box! Or maybe with a box. Who knows? You arrive as you are, a stranger in a strange land. -

Download Book / Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion

4RW0AHNJAEJL « eBook ~ Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion Filesize: 5.99 MB Reviews Complete guideline! Its this kind of good read. It can be writter in easy terms rather than difficult to understand. I am delighted to tell you that here is the very best book i have got go through during my very own lifestyle and might be he greatest ebook for at any time. (Bill Klein) DISCLAIMER | DMCA BGGLVTLG2OW2 » Doc « Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion DOCTOR WHO AND THE AUTON INVASION To read Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion PDF, remember to refer to the button under and download the file or have access to other information which might be have conjunction with DOCTOR WHO AND THE AUTON INVASION book. Ebury Publishing. Paperback. Book Condition: new. BRAND NEW, Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion, Terrance Dicks, Put on trial by the Time Lords, and found guilty of interfering in the aairs of other worlds, the Doctor is exiled to Earth in the 20th century, his appearance once again changed. His arrival coincides with a meteorite shower. But these are no ordinary meteorites. The Nestene Consciousness has begun its first attempt to invade Earth using killer Autons and deadly shop window dummies. Only the Doctor and UNIT can stop the attack. But the Doctor is recovering in hospital, and his old friend the Brigadier doesn't even recognise him. Can the Doctor recover and win UNIT's trust before the invasion begins? This novel is based on "Spearhead from Space", a Doctor Who story which was originally broadcast from 3-24 January 1970, featuring the Third Doctor as played by Jon Pertwee, his companion Liz Shaw and the UNIT organisation commanded by Brigadier Lethbridge- Stewart. -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen. -

Diary of the Doctor Who Role-Playing Games, Issue

VILLAINS ISSUE The fanzine devoted to Doctor Who Gaming ISSUE # 14 CONTINUITY„THIS IN GAMINGMACHINE - KILLSCH FASCISTS‰ ADVENTURE MODULE NEW FASA„MORE VILLAIN THAN STATS MONEY‰ - CREATING ADVENTURE GOOD VILLAINS MODULE and MORE...ICAGO TARDIS 2011 CON REPORT 1 EDITOR’S NOTES CONTENTS Hi there, Some of our issues feature a special theme, so we EDITOR’S NOTES 2 welcome you to our “Villains Issue”. This is a fanzine that REVIEW: The Brilliant Book 2012 3 concentrates on helping GMs create memorable and ef‐ Angus Abranson Leaving Cubicle 7 4 fective villains in their game. Villain motivations, villain Face to Face With Evil 5 tools and more can be found in these pages. Neil Riebe Not One, But Two, Episodes Recovered 11 even gives us retro FASA stats for Androgums, who can Why Are Your Doing This?! 12 be used as villains or standard characters. Hopefully Gamer Etiquette 105 14 there will be something fun for you to use in your next The Villain’s Toolkit 15 adventure. Continuity in Gaming 16 A review of the Chicago TARDIS 2012 convention New FASA Villain Stats: Androgums 18 is included in this issue, where our staff did a session on REVIEW: Everything I Need to Know I Learned From Doctor Who RPGs and also ran an adventure using the Dungeons & Dragons 23 Cubicle 7 DWAiTS rules as well. Staff member Eric Fettig MODULE: “This Machine Kills Fascists” 24 made it his first official Doctor Who convention (having EVENT REPORT: Chicago TARDIS 2011 Con 28 attended many gaming conventions before that) and Viewpoint of a First Time Who Con Attendee 43 gives us a look from his first timer’s perspective. -

Download from Our Site for All Readers Can I Take This Opportunity to Thank David Richardson for Filling of Doctor Who Magazine

ISSUE #6 AUGUST 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE STARGATE Neil Roberts reports from Atlantis DARK SHADOWS Author Stephen Mark Rainey on his latest audiobook SIXTH SENSE DALEKS, DRACONIANS, ICE WARRIORS, VIYRANS, SIL AND THE CELESTIAL TOYMAKER! it’s a busy year for sixth doctor colin baker! PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL Yes, I’m back, and this time it’s paternal! For those of you who at the Theatre Royal Nottingham from 10th to 15th of August, haven’t heard my son Benedict on the Big Finish July podcast, with matinees on 12th and 15th (that’s the Wednesday and the this is what he sounds like: ‘Waaaaaah!’. He does make other Saturday). Okay, plug over. noises, some of them a bit like the things Dick Mills used to get up to at the Radiophonic Workshop with swarfega, but I’ll leave Just time for some Big Finish plugs: The Mists of Time, a Jo Grant those to your imagination. Companion Chronicle by Jonathan Morris is still available as a free (yes, FREEEEE!) download from our site for all readers Can I take this opportunity to thank David Richardson for filling of Doctor Who Magazine. Just see the latest issue of DWM for in this slightly orange box for me last issue? I think I can, yes. the web address and special code. And you’ll also find on our And I’d like to link that thanks to a general thanks to David website that we’re offering ‘Big Finish for a Fiver!’ on selected Richardson for all the fine work he does for Big Finish… not releases, including Dalek Empire and Doctor Who Unbound. -

Arrowdown Doctor Who: Adventures in Time and Space Arrowdown

Sample file ARROWDOWN DOCTOR WHO: ADVENTURES IN TIME AND SPACE ARROWDOWN B CREDITS WRITING: Alasdair Stuart EDITING: Andrew Kenrick COVER: Paul Bourne GRAPHIC DESIGN AND LAYOUT: Paul Bourne CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Dominic McDowall ART DIRECTOR: Jon Hodgson S PECIAL THANKS: Georgie Britton and the BBC Team for all their help. Find out more about us and our games at www.cubicle7.co.uk © Cubicle 7 Entertainment Ltd. 2014 BBC, DOCTOR WHO (word marks, logos and devices), TARDIS, DALEKS, CYBERMAN and K-9 (wordmarks and devices) are trademarks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and are used under licence. BBC logo © BBC 1996. Doctor Who logo © BBC 2009. TARDIS image © BBC 1963. Dalek image © BBC/Terry Nation 1963. Cyberman image © BBC/Kit Pedler/Gerry Davis 1966. K-9 image © BBC/Bob Baker/Dave Martin 1977. B CONTENTS Introduction Sample3 file What’s Going On 3 Prologue 4 Scene One: Welcome to Arrowdown 4 Scene Two: Operation Timekeeper 9 Scene Three: Coming Like a Ghost Town 12 Scene Four: Merry Go Round 13 Scene Five: The Plastic Court 14 Scene Six: Monroe’s, Open For Business 15 2 DOCTOR WHO: ADVENTURES IN TIME AND SPACE ARROWDOWN ARROWDOWN B INTRODUCTION B WHAT’S GOING ON ‘Arrowdown’ is intended to be a fast moving scenario The effects of the Time War were missed by many lifeforms to guide you through the way the game works, give each in the universe, this can be said of the small coastal type of character a chance to shine and at the same time Yorkshire village of Arrowdown. When a Dalek fled with vital emphasise exactly how strange and dangerous the Doctor’s information using its Emergency Temporal Shift, it crashed world is. -

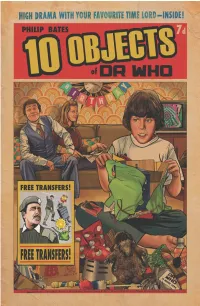

10 Objects of Dr

The right of Philip Bates to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. An unofficial Doctor Who Publication Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2021 Editor: Shaun Russell Editorial: Will Rees Cover and illustrations by Martin Baines Published by Candy Jar Books Mackintosh House 136 Newport Road, Cardiff, CF24 1DJ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Come one, come all, to the Museum of ! Located on the SS. Shawcraft and touring the Seven Systems, right now! Are you a fully-grown human adult? I would like to speak to someone in charge, so please direct me to any children in the vicinity. No, no, that's not fair – I was programmed not to judge, for I am a simple advertisement bot, bringing you the best in junk mail. Are you always that short? No, don’t look at me like that: my creators were from Ravan-Skala, where the people are six hundred ft tall; you have to talk to them in hot air balloons, and the tourist information centre is made of one of their hats. -

{PDF EPUB} Doctor Who Twelve Angels Weeping Twelve Stories of the Villains from Doctor Who by Dave Rudden Doctor Who: Twelve Angels Weeping

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who Twelve Angels Weeping Twelve stories of the villains from Doctor Who by Dave Rudden Doctor Who: Twelve Angels Weeping. On every planet that has existed or will exist, there is a winter . Many of the peoples of Old Earth celebrated a winter festival. A time to huddle together against the cold; a time to celebrate being half-way out of the dark. But shadows are everywhere, and there are some corners of the universe which have bred the most terrible things, lurking in the cold between the stars. Here are twelve stories - one for each of the Twelve Days of Christmas - to remind you that to come out of the darkness we need to go into it in the first place. We are not alone. We are not safe. And, whatever you do: don't blink. Written by popular children's author, and lifelong Doctor Who fan, Dave Rudden. Doctor Who: Twelve Angels Weeping: Twelve stories of the villains from Doctor Who. 2. Doctor Who: Twelve Angels Weeping: Twelve stories of the villains from Doctor Who. Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. BRAND NEW ** SUPER FAST SHIPPING FROM UK WAREHOUSE ** 30 DAY MONEY BACK GUARANTEE. Seller Inventory # mon0005712893. 3. Doctor Who: Twelve Angels Weeping. Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 41617204-n. 4. Doctor Who Twelve Angels Weeping. Book Description Condition: New. Bookseller Inventory # ST1405946083. Seller Inventory # ST1405946083. 5. Doctor Who: Twelve Angels Weeping: Twelve stories of the villains from Doctor Who (Paperback) Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English. Brand new Book. Twelve extraordinary Doctor Who stories, each featuring a monstrous villain from the Doctor Who world.On every planet that has existed or will exist, there is a winter . -

In the Shadow of the Silent Majorities ••• Or the End of the Social

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SILENT MAJORITIES ••• OR THE END OF THE SOCIAL AND OTHER ESSAYS FOREIGN AGENTS SERIES Jim Fleming and Sylvere Lotringer, Series Editors IN THE SHADOW OF THE SILENT MAJORmES Jean Baudrillard ONTHEUNE Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari DRIFTWORKS Jean-Francois Lyotard POPULAR DEFENSE AND ECOLOGICAL STRUGGLES Paul Virilio SIMULATIONS Jean Baudri liard THE SOCIAL FACTORY Toni Negri and Mario Tronti PURE WAR Paul Virilio JEAN BAUDRILLARD IN THE SHADOW OF THE SILENT MAJORITIES ••• OR THE END OF THE SOCIAL AND OTHER ESSAYS Translated by Paul Foss, Paul Patton and John Johnston Semiotext(e), Inc. 522 Philosophy Hall Columbia University New York City, New York 10027 ©1983, Jean Baudrillard and Semiotext(e) We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the New York State Council on the Arts. All right reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Contents In the Shadow of the Silent Majorities 1 ... Or, The End of the Social 65 The Implosion of Meaning in the Media 95 Ou r Theater of Cruelty 113 The whole chaotic constellation of the social revolves around that spongy referent, that opa que but equally translucent reality, that nothing ness: the masses. A statistical crystal ball, the masses are "swirling with currents and flows," in the image of matter and the natural elements. So at least they are represented to us. They can be "mesmerized," the social envelops them, like static electricity; but most of the time, precisely, they form an earth *, that is, they absorb all the *Translator's Note: Throughout the text "la masse," "fa ire masse" imply a condensation of terms which allows Baudrillard to make a number of central puns and allusions.