Giving up the Ghost of Enkidu, Comprehending Enkidu’S Ghosts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nabu 2015-2-Mep-Dc

ISSN 0989-5671 2015 N°2 (juin) NOTES BRÈVES 25) À propos d’ARET XII 344, des déesses dgú-ša-ra-tum et de la naissance du prince éblaïte* — Le texte administratif ARET XII 344 est malheureusement assez lacuneux, mais à notre avis quand même très intéressant. Les lignes du texte préservées sont les suivantes: r. I’:1’-5’: ‹x›[...] / šeš-[...] / in ⸢u₄⸣ / ḫúl / ⸢íl⸣-['à*-ag*-da*-mu*] v. II’:1’-11’: ...] K[ALAM.]KAL[AM(?)] / NI-šè-na-⸢a⸣ / ma-lik-tum / è / é / daš-dar / ap / íl-'à- ag-da-mu / i[n] / [...] / [...] r. III’:1’-9’: ⸢'à⸣-[...] / 1 gír mar-t[u] zú-aka / 1 buru₄-mušen 1 kù-sal / daš-dar / NAM-ra-luki / 1 zara₆-túg ú-ḫáb / 1 giš-šilig₅* 2 kù-sig₁₇ maš-maš-SÙ / 1 šíta zabar / dga-mi-iš r. IV’:1’-10’: ⸢x⸣[...] / 10 lá-3 an-dù[l] igi-DUB-SÙ šu-SÙ DU-SÙ kù:babbar / 10 lá-3 gú-a-tum zabar / dgú-ša-ra-tum / 5 kù-sig₁₇ / é / en / ni-zi-mu / 2 ma-na 55 kù-sig₁₇ / sikil r. V’:1’-6’: [x-]NE-[t]um / [x K]A-dù-gíd / [m]a-lik-tum / i[n-na-s]um / dga-mi-iš / 1 dib 2 giš- DU 2 ti-gi-na 2 geštu-lá 2 ba-ga-NE-su!(ZU) r. VI’:1’-6’: [...]⸢x⸣ / [m]a-[li]k-tum / [šu-ba₄-]ti / [x ki]n siki / [x-]li / [x-b]a-LUM. Tout d’abord, on remarquera qu’au début du texte on peut lire in ⸢u₄⸣ / ḫúl / ⸢íl⸣-['à*-ag*-da*- mu*], c’est-à-dire « dans le jour de la fête (en l’honneur) d’íl-'à-ag-da-mu ». -

NABU 2021 2 Compilé 07 Corr NZ

ISSN 0989-5671 2021 N° 2 (juin) NOTES BRÈVES 26) Kings’ ladies at Ebla’s court — The label ‘dam en list’ is used to refer to sections of several administrative tablets mentioning the female members of the Ebla royal family. These women appear in the documents along with other members of the court as the recipients of garments and/or precious objects. Three new, complete lists of dam en have been published since the last comprehensive study on the topic by Tonietti (1989), and several fragmentary lists appeared in Lahlou and Catagnoti (2006). In this note I shall offer an updated index of the dam en lists, providing a few general remarks which might facilitate access to this material to a non-specialist public. The group of women mentioned in the dam en lists includes different female members of the royal family. While Sumerian differentiates between human and non-human, Eblaite and other Semitic languages have two grammatical genders. We thus translate the Sumerian term dam (“spouse”) as “wife” or “(adult) woman” depending on the context. However, the scribes of the Archives used the label dam en rather inconsistently, at times including in this group women who had a different kin relationship with the king (Biga 1987). Three facts corroborate this statement. First, in some lists, such as R₁ (see Table 1) the scribes made a clear distinction between the king’s wives, addressed as dam en (Raʿutum, Kiršūt, Ḥinna-Šamaš, Rapeštum, Mašgašatu, Maqaratu, Tašma-Damu, Rapeštum-II), his daughters who are called dumu-mi₂ en (Maʾut, Ṣanīʿī-Mari), as well as several other high ranking women. -

The Lost Book of Enki.Pdf

L0ST BOOK °f6NK1 ZECHARIA SITCHIN author of The 12th Planet • . FICTION/MYTHOLOGY $24.00 TH6 LOST BOOK OF 6NK! Will the past become our future? Is humankind destined to repeat the events that occurred on another planet, far away from Earth? Zecharia Sitchin’s bestselling series, The Earth Chronicles, provided humanity’s side of the story—as recorded on ancient clay tablets and other Sumerian artifacts—concerning our origins at the hands of the Anunnaki, “those who from heaven to earth came.” In The Lost Book of Enki, we can view this saga from a dif- ferent perspective through this richly con- ceived autobiographical account of Lord Enki, an Anunnaki god, who tells the story of these extraterrestrials’ arrival on Earth from the 12th planet, Nibiru. The object of their colonization: gold to replenish the dying atmosphere of their home planet. Finding this precious metal results in the Anunnaki creation of homo sapiens—the human race—to mine this important resource. In his previous works, Sitchin com- piled the complete story of the Anunnaki ’s impact on human civilization in peacetime and in war from the frag- ments scattered throughout Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Hittite, Egyptian, Canaanite, and Hebrew sources- —the “myths” of all ancient peoples in the old world as well as the new. Missing from these accounts, however, was the perspective of the Anunnaki themselves What was life like on their own planet? What motives propelled them to settle on Earth—and what drove them from their new home? Convinced of the existence of a now lost book that formed the basis of THE lost book of ENKI MFMOHCS XND PKjOPHeCieS OF XN eXTfCXUfCWJTWXL COD 2.6CHXPJA SITCHIN Bear & Company Rochester, Vermont — Bear & Company One Park Street Rochester, Vermont 05767 www.InnerTraditions.com Copyright © 2002 by Zecharia Sitchin All rights reserved. -

NABU 2021 1 Compilé 09 Corr DC

ISSN 0989-5671 2021 N° 1 (mars) NOTES BRÈVES 1) Ebla: how many years? — Essays on Ebla by the philologists who collaborate with the Archaeological Expedition to Ebla of the University of Rome – La Sapienza are published rather frequently, one after the other. They concern a society which is different in some way from those studied by other specialists of third millennium B.C. Ebla is something like a New World: personal names and many geographic names sound alien to these colleagues; some documentary forms are unusual; the lexicon coincides in large part, but not completely, with that of the Mesopotamian documents; Sumerian names are applied to local deities. No one can follow everything and must therefore rely (sometimes perhaps with a grain of salt) on what Eblaitologists say. Too many things are not as clear as one would wish, but this is what stimulates research. The situation becomes uncomfortable, however, if Eblaitologists disagree with each other on some basic features. This predicament is evident comparing the two essays, which in some way also concern Ebla, that appear in The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East I (K. Radner ed.), New York 2020, an opus intended to replace the glorious Cambridge Ancient History, as far as the Ancient Near East is concerned. V. Bartash, author of chapter 8, “The Early Dynastic Near East”, gives a concise picture of the Ebla state basing himself on the interpretations offered by the philologists of the Ebla Expedition (Bartash 2020: 579–583). P. Michalowski, author of chapter 10, “The kingdom -

Andrew George, What's New in the Gilgamesh Epic?

What’s new in the Gilgamesh Epic? ANDREW GEORGE School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Summary. The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic exists in several different versions. There were at least two versions current during the Old Babylonian period, and no doubt a similar situation obtained later in the second millennium BC, when versions of the epic were copied out in Anatolia, Syria and Palestine, as well as in Mesopotamia proper. But the best-known version is the one called “He who saw the Deep”, which was current in the first-millennium libraries of Assyria and Babylonia. Because this text was so much copied out in antiquity we keep finding more of it, both in museums and in archaeological excavation. This means that editions and translations of the epic must regularly be brought up to date. Some of the more important new passages that are previously unpublished are presented here in translation. WHAT THERE IS It was a great pleasure to be able to share with the Society at the symposium of 20 September 1997 some of the results of my work on the epic of Gilgamesh. My paper of this title was given without a script and was essentially a commentary on the slides that accompanied it. The written paper offered here on the same subject tells the story from the standpoint of one year later. Being the written counterpart of an oral presentation, I hope it may be recognized at least as a distant cousin of the talk given in Toronto. I should say at the outset that my work has been concerned primarily with the textual material in the Akkadian language, that is to say, with the Babylonian poems. -

NABU 1990-121 Paul-Alain Beaulieu

NABU 1990-121 Paul-Alain Beaulieu Lion-Man: uridimmu or urdimmu ? – In AfO 18 (1957-58) 109-112 W.G. Lambert published and edited «A Part of the Ritual for the Substitute King∞, which prescribes the fashioning of figurines of mythical creatures and their burial at various locations in the palace. One section (column B 10-11) gives instructions to make «two Raging Dogs of tamarisk wood, holding crescents of cedar in their hands∞. The word «Raging Dog∞ is not written ur.idim.mu, however, but phonetically ur-dím-me (or ur-dímme), and Lambert raised the question if ur.idim.mu should not always be read without the /i/. His suggestion is not retained by von Soden (AHw s.v. uridimmu) who considers the spelling ur-dím-me might be a mistake. Borger (Zeichenliste p. 196) prudently transcribes the word ur(i)dimmu. The most recent treatment of the question is by F.A.M. Wiggerman, Babylonian Prophylactic Figures: The Ritual Texts, Amsterdam, Free University Press, 1986, pp. 299-302. Wiggerman has identified the ur(i)dimmu as a human- headed lion-man crowned with a tiara and holding a staff with a lunar crescent on top1, thus rejecting the earlier interpretation «Raging Dog, Wild Dog∞, which was based on the lexical equivalence ur.dim = kal-bu ße-gu-ú in MSL 8/II (·AR-ra = ⁄ubullu XIV, 95). Although he uses the form uridimmu throughout his book, Wiggerman recognizes that the correct Akkadian form of the word might be urdimmu in consideration of the following two additional instances of syllabic spellings without the /i/: Cavigneaux, Texts from Babylon I, 105, 4 mulur.idim = [u]r-dim-mu YOS 17 345, 6 ∂ur-dim-mu YOS 17 345 is a text from Uruk dated to the 12th year of Nebuchadnezzar II. -

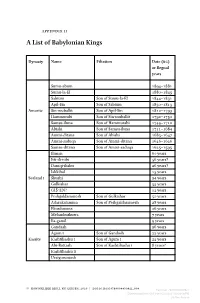

A List of Babylonian Kings

Appendix II A List of Babylonian Kings Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Sumu-abum 1894–1881 Sumu-la-El 1880–1845 Sabium Son of Sumu-la-El 1844–1831 Apil-Sin Son of Sabium 1830–1813 Amorite Sin-muballit Son of Apil-Sin 1812–1793 Hammurabi Son of Sin-muballit 1792–1750 Samsu-iluna Son of Hammurabi 1749–1712 Abishi Son of Samsu-iluna 1711–1684 Ammi-ditana Son of Abishi 1683–1647 Ammi-saduqa Son of Ammi-ditana 1646–1626 Samsu-ditana Son of Ammi-saduqa 1625–1595 Iliman 60 years Itti-ili-nibi 56 years? Damqi-ilishu 26 years? Ishkibal 15 years Sealand I Shushi 24 years Gulkishar 55 years GÍŠ-EN? 12 years Peshgaldaramesh Son of Gulkishar 50 years Adarakalamma Son of Peshgaldaramesh 28 years Ekurduanna 26 years Melamkurkurra 7 years Ea-gamil 9 years Gandash 26 years Agum I Son of Gandash 22 years Kassite Kashtiliashu I Son of Agum I 22 years Abi-Rattash Son of Kashtiliashu I 8 years? Kashtiliashu II Urzigurumash © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_009 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 09:29:36PM via free access A List of Babylonian Kings 203 Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Harba-Shipak Tiptakzi Agum II Son of Urzigurumash Burnaburiash I […]a Kashtiliashu III Son of Burnaburiash I? Ulamburiash Son of Burnaburiash I? Agum III Son of Kashitiliash IIIb Karaindash Kadashman-Harbe I Kurigalzu I Son of Kadashman-Harbe I Kadashman-Enlil I 1374?–1360 Burnaburiash II Son of Kadashman-Enlil I? 1359–1333 Karahardash Son of Burnaburiash II? 1333 Nazibugash Son of Nobody -

The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State D

Cambridge University Press 0521563585 - The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State D. T. Potts Index More information INDEX A’abba, 179 Aleppo, 169, 170 Apollophanos, 364, 369 Aahitek, 207, 208 Alexander, the Great, 348–50, apples, 137 Abadan, 14 355; I Balas, 373, 383, 387, 388 Arahir, 136 Aba-Enlilgim, 140 al-Hiba, 92, 95 Aramaic, 384, 399, 424 Abalgamash, 105, 106 Ali Kosh, see Tepe Ali Kosh Arashu, 285 Abbashaga, 135, 140 Allabria, 263 Arawa, 89; see also Urua Ab-i-Diz, see Diz Allahad, 168 Arbimazbi, 140 Ab-i-Marik, 22 almond, 155 Archalos, 349 Abiradu, 328 Altyn-depe, 118 archons, at Susa, 363 Abu Fanduweh, 55 Alumiddatum, 136, 138, 141 Ardashir, 410–16, Fig. 11.2 Abu Salabikh, 58, 88, 242 Amar-Sin, 135, 137, Areia, 323 Abulites, 348–50 ambassadors, 138–9 Argishti-henele, 301 Aburanum, 137 amber, 33 Ariaramnes, 287 accountancy, 59–60 Amedirra, 283 Arjan, 124, 303–6, 412 Achaemenes, 287 Amel-Marduk, 293 armour, 203, 277 Açina, 317–18 Ammiditana, 171 aromatics, see incense Acropole, see Susa, Acropole Ammisaduqa, 165, 189 Arrapha/Arraphe, 242 Acts, Book of (2.9), 3 Amorites, 167 arrowheads, copper/bronze, 95 Adab, 121 Ampe, 391 Arsaces, 376–7, 388, 391, 392 Adad, 347 Ampirish, 306 Arsames, 287 Adad-erish, 204 Amurru, 193 arsenic, 218 Adad-nirari III, 263 Amygdalus, 23 Artabanus I, 391; II, 391; III, 369; Adad-rabi, 177 An(?)turza, 347 IV, 401, 412 Adad-sharru-rabu, 191 Anahita, 383 Artaxerxes I, 335, 337, 318; II, 7, Adad-shuma-iddina, 231 Anarak, 33, 34 335, 337, 359; III, 339 Adad-shuma-usur, -

Abhiyoga Jain Gods

A babylonian goddess of the moon A-a mesopotamian sun goddess A’as hittite god of wisdom Aabit egyptian goddess of song Aakuluujjusi inuit creator goddess Aasith egyptian goddess of the hunt Aataentsic iriquois goddess Aatxe basque bull god Ab Kin Xoc mayan god of war Aba Khatun Baikal siberian goddess of the sea Abaangui guarani god Abaasy yakut underworld gods Abandinus romano-celtic god Abarta irish god Abeguwo melansian rain goddess Abellio gallic tree god Abeona roman goddess of passage Abere melanisian goddess of evil Abgal arabian god Abhijit hindu goddess of fortune Abhijnaraja tibetan physician god Abhimukhi buddhist goddess Abhiyoga jain gods Abonba romano-celtic forest goddess Abonsam west african malicious god Abora polynesian supreme god Abowie west african god Abu sumerian vegetation god Abuk dinkan goddess of women and gardens Abundantia roman fertility goddess Anzu mesopotamian god of deep water Ac Yanto mayan god of white men Acacila peruvian weather god Acala buddhist goddess Acan mayan god of wine Acat mayan god of tattoo artists Acaviser etruscan goddess Acca Larentia roman mother goddess Acchupta jain goddess of learning Accasbel irish god of wine Acco greek goddess of evil Achiyalatopa zuni monster god Acolmitztli aztec god of the underworld Acolnahuacatl aztec god of the underworld Adad mesopotamian weather god Adamas gnostic christian creator god Adekagagwaa iroquois god Adeona roman goddess of passage Adhimukticarya buddhist goddess Adhimuktivasita buddhist goddess Adibuddha buddhist god Adidharma buddhist goddess -

Babylonian Legal and Business Documents from the Time

THE BABYLONIAN EXPEDITION THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA SERIES A: CUNEIFORM TEXTS EDITED BY H. V. HILPRECHT VOLUME VI, PART1 BY HERMANN RANKE - ECKLEY BRINTON COXE. JUNIOR, FUND " PHILADELPHIA Pu6lished by the Department of Archaeology, University of Pennsylvania 1906 HE EDITOR determines the material to constitute a volume and T reports to the Committee of Publication on the general merits of the manuscript and autograph plates submitted for publication: but the Editor is not responsible for the views expressed by the writer. BABYLONIAN LEGAL AND BUSINESS DOCUMENTS FROM THE TIME OF TIIE FIRST DYNASTY 01.'BABYLON CHIEFLY FROM SIPPAR HERMANN RANKE. PH.D. I I Hll,FSARBEITBR A. D. AEOYPTISCHEN ABTEILUNG U. I<aNIGL. hlllS~BN, BER~IN, GERMANY FORMEBLYIIIBRISON RESEABCHFRLLOW IN ASSYRIOLOOV. .UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA 71 Plates of Autographed Texts and 13 Plates of Halftone Illustrations PHILADELPHIA Published by the Deparfmenf or Archaeology, 'University of Pennsylvania 1906 MACCAI.LA & Go. Inc.. Printers C. H. J&XES, Lithographer WEEKS PHOTO-ENOBAYINGCo., Ualftones I=o Hlbert Zobias Clap haaiatunt $lrnfemnr nf Bemitir $lhilnlngy an3 Arr$uenlngy at the Pniuereiql nf $lmnsyluunia Chis Volume is Dedicated in :%inr~rpfri~nbship unh gdiiube, PREFACE. The copies of the 119 texts here publishcd have been made in Philadelphia during the ycars 1902-1905. The photograph reproductions of some of the tablets, for which I am greatly obliged to the skill of Mr. W. H. Witte, of the Free Museum of Science and Art, will enable the reader to test the accuracy of the copies. The printing had to be done after I had returnecl t,o Germany and thus consumed a considerable amount of tirne. -

•1 Rently >->-| *~1^F ^ » *-*-Y H & *~^"F ^""Hf" ^E-^T' '• Or *->~Y Hhf -^"Flf"

•1 402 ON THE ORTHOGRAPHY OF THE * examples, Nabunit naming himself on his bricks and cylinders indiffe- ; rently >->-| *~1^f ^» or *-*-Y H& *~^"f ^""Hf" ^E-^T' '• or *->~y HHf -^"flf" J^J-» an(* *^e *^ree several and equivalent • forms occurring not unfrequently in the course-of the same inscription I do not pretend at present to explain how it happens thai -^•77 JAI has the phonetic power of nit, but the fact is undoubted, and Dr. Hincks therefore must abandon all his readings of Nabu-bin~ yuchur, Shamsi bin, Ben-Hadad, Assur-yuchura-bal, together with his three sons of Esar-Haddon, and a number of other historical illustra- * tions, which he has recently delivered "ex cathedra," with the same ,; confidence that characterizes his announcement of genuine readings, * and which are thus calculated to mislead enquiry, and to retard the progress of discovery. The only single addition which I have to make to my sketch of Assyrian history, as published in the Athen&um of March, 1854, is, that in the S. E. palace at Nimrud many relics have been recently found of the son of Asshur-bani-pal, whom I name provisionally A sshur-emit-ili,1 and that under this king, who reigned probably from B.C. 045 to 625, must therefore be placed both the Scythian inroad and the destruction of Nineveh by the Medes. H. C. RAWLINSON. Letter from Dr. Hincks, in reply to Colonel Hawlinson's Note on the Successor of Sennacherib. Killyleigh, Co. Down, 29th Fov. 1854. Dear Sir. I observe that a communication from Colonel Rawlinson was read at the last meeting of the Royal Asiatic Society, containing what he conceived to be rectifications of statements made by me in a report and letter of mine published in the Literary Gazette. -

Ancient-Knowledge-Networks.Pdf

Ancient Knowledge Networks Ancient Knowledge Networks A Social Geography of Cuneiform Scholarship in First-Millennium Assyria and Babylonia Eleanor Robson First published in 2019 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.uclpress.co.uk Text © Eleanor Robson, 2019 Images © Eleanor Robson and copyright holders named in captions, 2019 The author has asserted her rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non- derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Robson, E. 2019. Ancient Knowledge Networks: A Social Geography of Cuneiform Scholarship in First-Millennium Assyria and Babylonia. London: UCL Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787355941 Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons license unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. If you would like to re-use any third-party material not covered by the book’s Creative Commons license, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. ISBN: 978-1-78735-596-5 (Hbk.) ISBN: 978-1-78735-595-8 (Pbk.) ISBN: 978-1-78735-594-1 (PDF) ISBN: 978-1-78735-597-2 (epub) ISBN: 978-1-78735-598-9 (mobi) DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787355941 In memory of Bo Treadwell (1991–2014) Contents List of illustrations ix List of tables xv Acknowledgements xvi Bibliographical abbreviations xix Museum and excavation sigla xxi Dating conventions xxii Editorial conventions xxiii 1.