Programnotes Mozart Turkishc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

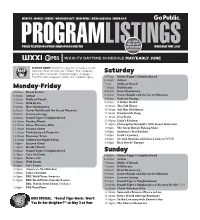

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

Alternately Known As 1313; Originally Releases 1977 by UZ, 1977 by Atem, Numerous Intervening Reissues, 1990 by Cuneiform

UNIVERS ZERO UNIVERS ZERO CUNEIFORM 2008 REISSUE W BONUS TRACKS & REMASTER (alternately known as 1313; originally releases 1977 by UZ, 1977 by Atem, numerous intervening reissues, 1990 by Cuneiform) Cuneiform 2008 album features: Michel Berckmans [bassoon], Daniel Denis [percussion], Marcel Dufrane [violin], Christian Genet [bass], Patrick Hanappier [violin, viola, pocket cello], Emmanuel Nicaise [harmonium, spinet], Roger Trigaux [guitar], and Guy Segers [bass, vocal, noise effects] “ALBUM OF THE WEEK...Released in 1977, it was astonishing then: today, it sounds like the hidden source for every one of today's avant-garde rock bands. Chillingly beautiful, driven by the bassoon and cello more than the guitar and synth, each instrumental is both pastoral and burgeoning with terrible life. … This is edgy beyond belief. …Each piece magnificently refuses to deviate from its mood, its tense, thrilling, growling, restrained focus... The whole is like the rare, delicious bits of great film soundtrack that create menace and energy out of nowhere. … Univers Zero are a revelation …” – Sean O., Organ, #274, September 18th, 2008 “UZ's debut remains both benchmark and landmark. Reissued numerous times over the years…this definitive version finally presents this unprecedented music the way it was meant to be heard, clarifying how—emerging out of nowhere with little history to precede it— UZ has been so vital in changing the way chamber music is perceived. UZ's music was an antecedent for the kind of instrumental and stylistic interspersion considered normal today by groups including Bang on a Can and Alarm Will Sound. Henry Cow's complex, abstruse writing meets Bartok, Stravinsky, Messiaen and Ligeti, but with hints of early music, especially in UZ's use of spinet and harmonium. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Programme 5 Overview 6 Schedule First Word 12 Greeting Andreas

Index Programme Expo 5 Overview 44 Umbrella Stands A – Z 6 Schedule 47 Exhibitor Presentation/Expo Map 84 Exhibitors A – Z First Word 12 Greeting Andreas Mailath-Pokorny, Conference Executive City Councillor for Cultural Affairs 90 Conference Sessions and Science, City of Vienna 100 Mentoring 13 Greeting Rainer Kahleyss and Werner 102 Network Meetings and Presentations Dabringhaus, CLASS Association of Classical 104 Biographies A – Z Independents in Germany 14 Greeting Mario Rossori, Heinrich Schläfer, Film Screenings Frank Stahmer, Classical Partners Vienna 1 11 Film Screenings 15 Greeting Jennifer Dautermann, Director Classical:NEXT Showcases 115 Opening and Closing Network 116 Live Showcases A – Z 18 Advisory Board 130 Video Showcases A – Z 20 The Jury 136 off C:N Showcases A – Z 22 Partners 26 Photographer Delegates 27 Advertisers A – Z 142 Companies A – Z 177 Individuals A – Z Classical:NEXT A – Z 30 From ”Badges" to ”Who is Coming“ Credits 190 Imprint Destination Vienna 191 Team 37 Getting Around 37 Places to Eat 39 Shopping: Food, Music and Instruments Front Flap Inside Plant Layout MAK 41 Things to See Back Flap Inside Directions to Venues 42 Service NEW YEAR. NEW STORIES. PROGRAMME NEW CLASSICAL MUSIC. First Word Network C:N A – Z Destination Vienna Expo FROM Conference £4.95 A Film Screenings MONTH Showcases Delegates Credits The all-new Classical Music: Register online » Comprehensive website with news, features, reviews and opinion for FREE access » Daily e-mail bulletin with news from national and international press to classical -

Program Notes: Inspiration & Impact

CABRILLO FESTIVAL Program Notes: Inspiration & Impact Lola Montez Does the and she glides from the stage of sensory and expressive overload. Spider Dance (2016) overwhelmed with applause, At its premiere in March of 2012, the first third and smashed spiders, John Adams of the piece was largely a trope on the Opus (b. 1947) and radiant with parti-colored skirts, [World Premiere] 131 C# minor quartet’s scherzo and suffered smiles, graces, cobwebs and glory. from just this problem. After a moody opening of tremolo strings and fragments of the Ninth Commissioned by the musicians of the Cabrillo Lola Montez Does the Spider Dance was Symphony signal octave-dropping motive, Festival Orchestra in honor of Marin Alsop commissioned by members of the Cabrillo Festival Orchestra in celebration of Marin the solo quartet emerged as if out of a haze, The Irish-born actress and dancer Eliza Gilbert Alsop’s twenty five seasons as music director, playing the driving foursquare figures of that (1821—1861) achieved international fame and it is dedicated to her. scherzo material that almost immediately went under the name “Lola Montez, the Spanish through a series of strange permutations. Dancer.” After a controversial career on the —John Adams continent, including a sojourn in Bavaria This original opening never satisfied me. The where she become both the lover as well as clarity of the solo quartet’s role was often political advisor to King Ludwig, she returned Absolute Jest (2011) buried beneath the orchestral activity resulting in what sounded to me too much like “chatter.” to London, where she eloped with and married John Adams (b. -

Joana Carneiro Music Director

JOANA CARNEIRO MUSIC DIRECTOR Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 16 Berkeley Sound Composer Fellows & Full@BAMPFA 18 Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Calendar 21 Tonight’s Program 23 Program Notes 37 About Music Director Joana Carneiro 39 Guest Artists & Composers 43 About Berkeley Symphony 44 Music in the Schools 47 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 49 Annual Membership Support 58 Broadcast Dates 61 Contact 62 Advertiser Index Media Sponsor Gertrude Allen • Annette Campbell-White & Ruedi Naumann-Etienne Official Wine Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Getty • Jill Grossman Sponsor Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Tricia Swift S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No photographs or recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. October 5 & 6, 2017 3 4 October 5 & 6, 2017 Message from the Music Director Dear Friends, Happy New Season 17/18! I am delighted to be back in Berkeley after more than a year. There are three beautiful reasons for photo by Rodrigo de Souza my hiatus. I am so grateful for all the support I received from the Berkeley Symphony musicians, members of the Board and Advisory Council, the staff, and from all of you throughout this special period of my family’s life. -

Taking Flight Beginning with a Tribute to Lindbergh, the St

TAKING FLIGHT BEGINNING WITH A TRIBUTE TO LINDBERGH, THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY EXPRESSES THE SPIRIT OF ST. LOUIS. BY EDDIE SILVA DILIP VISHWANAT David Robertson Begin with a new beginning. The St. Louis Symphony’s 2016-17 season, its 137th, starts with the turn of a propeller, a steep rise into uncluttered skies, and a lonely, perilous journey that changed how people lived, thought, and dreamed. Charles Lindbergh’s silvery craft was christened The Spirit of St. Louis, and pilot and aircraft made their historic flight together across the Atlantic 90 years ago. The name “Spirit of St. Louis” also reflects upon the daring and innovation of a few St. Louisans early in the 20th century. It also speaks to St. Louis now, near the beginning of a new century amidst a whirlwind of innovation that turns more swiftly than a propeller. The St. Louis Symphony, Music Director David Robertson has remarked often, embodies that spirit: innovative, daring, risk-taking, enduring, agile, resourceful—give it an engine and a pair of wings and you’ll see Paris by morning. Kurt Weill’s The Flight of Lindbergh opens the 2016-17 season (September 16-17). Described as a “radio cantata,” it is one of the early collaborations between Weill and Bertolt Brecht, who created the classic The Threepenny Opera as well as other distinctive Brecht/Weill productions. KMOX’s Charlie Brennan provides the radio expertise as narrator of The Flight of Lindbergh. This 1929 work, written in the flush of inspiration that followed Lindbergh’s 6 Taking Flight achievement, will feel fresh, new, and innovative in 2016. -

Prospero's Rooms

2020 FEB HADELICH PLAYS PAGANINI 2019-20 HAL & JEANETTE SEGERSTROM FAMILY FOUNDATION CLASSICAL SERIES Michael Francis, conductor Rouse PROSPERO’S ROOMS Augustin Hadelich, violin Paganini VIOLIN CONCERTO NO. 1 IN D MAJOR Allegro maestoso Adagio Rondo: Allegro spiritoso Augustin Hadelich Intermission Rachmaninoff SYMPHONY NO. 3 IN A MINOR Lento—Allegro moderato—Allegro Adagio ma non troppo—Allegro Allegro—Allegro vivace Thursday, February 27, 2020 @ 8 p.m. Friday, February 28, 2020 @ 8 p.m. The appearances of Augustin Hadelich and Saturday, February 29, 2020 @ 8 p.m. Michael Francis have been generously underwritten by Segerstrom Center for the Arts a gift from Sam and Lyndie Ersan. Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall OFFICIAL MEDIA SPONSOR This concert is being recorded for broadcast on Sunday, March 15, 2020, on Classical KUSC. PacificSymphony.org FEB 2020 5 PROGRAM NOTES in the world of atonality; yet he was also a influenced his compositional as well as rock’n’roll fan (Led Zeppelin was a favorite) his playing style. and taught a class on the history of rock None of this even begins to suggest Christopher Rouse: while on the faculty at the Eastman School the nature or extent of Paganini’s of Music. celebrity, which spread through Italy Prospero’s Rooms Regarding Prospero’s Rooms, Rouse and then took Europe by storm. After an Lovers of classical noted on his website: “In the days when I 1813 concert at Milan’s La Scala opera music lost one would have still contemplated composing house, he was spoken of in the same of their own in an opera, my preferred source was Edgar reverential tones as other great violinists, 2019 when the Allan Poe’s ‘Masque of the Red Death.’… including Charles Philippe Lafont and Pulitzer Prize- However… I decided to redirect my ideas Louis Spohr. -

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Announce Electrifying 2019/20 Season Strauss’ Masterpiece the Pinnacle of a High-Octane Year: Karabits, Montero and More

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Announce Electrifying 2019/20 Season Strauss’ masterpiece the pinnacle of a high-octane year: Karabits, Montero and more 2 October 2019 – 13 May 2020 Kirill Karabits, Chief Conductor of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra [credit: Konrad Cwik] EMBARGO: 08:00 Wednesday 15 May 2019 • Kirill Karabits launches the season – his eleventh as Chief Conductor of the BSO – with a Weimar- themed programme featuring the UK premiere of Liszt’s melodrama Vor hundert Jahren • Gabriela Montero, Venezuelan pianist/composer, is the 2019/20 Artist-in-Residence • Concert staging of Richard Strauss’s opera Elektra at Symphony Hall, Birmingham and Lighthouse, Poole under the baton of Karabits, with a star-studded cast including Catherine Foster, Allison Oakes and Susan Bullock • The Orchestra celebrates the second year of Marta Gardolińska’s tenure as BSO Leverhulme Young Conductor in Association • Pianist Sunwook Kim makes his professional conducting debut in an all-Beethoven programme • The Orchestra continues its Voices from the East series with a rare performance of Chary Nurymov’s Symphony No. 2 and the release of its celebrated Terterian performance on Chandos • Welcome returns for Leonard Elschenbroich, Ning Feng, Alexander Gavrylyuk, Steven Isserlis, Simone Lamsma, John Lill, Carlos Miguel Prieto, Robert Trevino and more • Main season debuts for Jake Arditti, Stephen Barlow, Andreas Bauer Kanabas, Jeremy Denk, Tobias Feldmann, Andrei Korobeinikov and Valentina Peleggi • The Orchestra marks Beethoven’s 250th anniversary, with performances by conductors Kirill Karabits, Sunwook Kim and Reinhard Goebel • Performances at the Barbican Centre, Sage Gateshead, Cadogan Hall and Birmingham Symphony Hall in addition to the Orchestra’s regular venues across a 10,000 square mile region in the South West Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra announces its 2019/20 season with over 140 performances across the South West and beyond. -

JS BACH (1685-1750): Violin and Oboe Concertos

BACH 703 - J. S. BACH (1685-1750) : Violin and Oboe Concertos Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21 st , l685, the son of Johann Ambrosius, Court Trumpeter for the Duke of Eisenach and Director of the Musicians of the town of Eisenach in Thuringia. For many years, members of the Bach family throughout Thuringia had held positions such as organists, town instrumentalists, or Cantors, and the family name enjoyed a wide reputation for musical talent. By the year 1703, 18-year-old Johann Sebastian had taken up his first professional position: that of Organist at the small town of Arnstadt. Then, in 1706 he heard that the Organist to the town of Mülhausen had died. He applied for the post and was accepted on very favorable terms. However, a religious controversy arose in Mülhausen between the Orthodox Lutherans, who were lovers of music, and the Pietists, who were strict puritans and distrusted art. So it was that Bach again looked around for more promising possibilities. The Duke of Weimar offered him a post among his Court chamber musicians, and on June 25, 1708, Bach sent in his letter of resignation to the authorities at Mülhausen. The Weimar years were a happy and creative time for Bach…. until in 1717 a feud broke out between the Duke of Weimar at the 'Wilhelmsburg' household and his nephew Ernst August at the 'Rote Schloss’. Added to this, the incumbent Capellmeister died, and Bach was passed over for the post in favor of the late Capellmeister's mediocre son. Bach was bitterly disappointed, for he had lately been doing most of the Capellmeister's work, and had confidently expected to be given the post. -

Lulu and the Performance of Unfinishedness Downloaded from by Guest on 04 January 2020

An Incomplete Life: Lulu and the Performance of Unfinishedness Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oq/article-abstract/35/1-2/20/5559520 by guest on 04 January 2020 January 04 on guest by https://academic.oup.com/oq/article-abstract/35/1-2/20/5559520 from Downloaded axel englund stockholm university What does unfinishedness mean to opera criticism in the wake of the performative turn? One familiar answer suggests that it means everything. Toward the end of the millennium, as live performance became a central focus of opera studies, the idea of a definitive version of an operatic text came to seem less and less appealing, as did the very notion of an operatic “work.”1 Instead, scholars valorized the elusive, mutable, or open-ended, and opera itself was imagined as an unfinished business, its ontology anchored in the moment of performance. But if the performative turn celebrated “unfinishedness,” it also rendered the concept oddly void of meaning. Strictly speaking, the finishedness of an opera can only be measured against one version or another of the work concept. Once the composer’s intention has lost its authority and the essence of an opera is situated less in its script than in its live in- stantiation, what does it mean to speak of an unfinished opera? If the locus of opera is the performance rather than the score, can Turandot be said to be any less com- plete than Tosca just because Alfano or Berio wrote the notes for the final scene? If the work is recast as a unique event that concludes every time the curtain falls, what space is left for the inconclusive? Although these questions have a bearing on opera criticism in general, they de- rive from my engagement with one particular opera, and in this article I will reroute them back into it: Alban Berg’s Lulu, which the composer struggled with from the late 1920s until his death in 1935.2 In November of that year, Berg suffered an unfor- tunate insect bite that would lead to his death by blood poisoning on Christmas Eve. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners.