Real Estate and Late Urbanization in Kigali and Addis Ababa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East and Central Africa 19

Most countries have based their long-term planning (‘vision’) documents on harnessing science, technology and innovation to development. Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twingiyimana A schoolboy studies at home using a book illuminated by a single electric LED lightbulb in July 2015. Customers pay for the solar panel that powers their LED lighting through regular instalments to M-Kopa, a Nairobi-based provider of solar-lighting systems. Payment is made using a mobile-phone money-transfer service. Photo: © Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images 498 East and Central Africa 19 . East and Central Africa Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo (Republic of), Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twiringiyimana Chapter 19 INTRODUCTION which invest in these technologies to take a growing share of the global oil market. This highlights the need for oil-producing Mixed economic fortunes African countries to invest in science and technology (S&T) to Most of the 16 East and Central African countries covered maintain their own competitiveness in the global market. in the present chapter are classified by the World Bank as being low-income economies. The exceptions are Half the region is ‘fragile and conflict-affected’ Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, Djibouti and the newest Other development challenges for the region include civil strife, member, South Sudan, which joined its three neighbours religious militancy and the persistence of killer diseases such in the lower middle-income category after being promoted as malaria and HIV, which sorely tax national health systems from low-income status in 2014. -

The Rwandan Genocide

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Town Cape of University Mass Murder and Motivation: The Rwandan Genocide ASMUND AAMAAS (amsasmOOl) A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Jewish Studies Faculty of the Humanities Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies University of Cape Town 2007 Supervisors: Professor Milton Shain and Professor Mohamed Adhikari University of Cape Town Declaration: This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Acknowledgment The motivation for writing this thesis has its roots in a highly interesting course on Holocaust and mass murder convened and led by Professor Milton Shain at the University of Cape Town in 2003. The seminar was the main reason why I choose to write this thesis. I am truly grateful to my supervisor Professor Shain for letting me do this project and for valuable comments along the process of writing it. Thank you also to my co supervisor Professor Mohamed Adhikari for helpful comments on the thesis. -

O C E a N O C E a N C T I C P a C I F I C O C E a N a T L a N T I C O C E a N P a C I F I C N O R T H a T L a N T I C a T L

Nagurskoye Thule (Qanaq) Longyearbyen AR CTIC OCE AN Thule Air Base LAPTEV GR EENLA ND SEA EAST Resolute KARA BAFFIN BAY Dikson SIBERIAN BARENTS SEA SEA SEA Barrow SEA BEAUFORT Tiksi Prudhoe Bay Vardo Vadso Tromso Kirbey Mys Shmidta Tuktoyaktuk Narvik Murmansk Norilsk Ivalo Verkhoyansk Bodo Vorkuta Srednekolymsk Kiruna NORWEGIAN Urengoy Salekhard SEA Alaska Oulu ICELA Anadyr Fairbanks ND Arkhangelsk Pechora Cape Dorset Godthab Tura Kitchan Umea Severodvinsk Reykjavik Trondheim SW EDEN Vaasa Kuopio Yellowknife Alesund Lieksa FINLAND Plesetsk Torshavn R U S S Yakutsk BERING Anchorage Surgut I A NORWAY Podkamennaya Tungusk Whitehorse HUDSON Nurssarssuaq Bergen Turku Khanty-Mansiysk Apuka Helsinki Olekminsk Oslo Leningrad Magadan Yurya Churchill Tallin Stockholm Okhotsk SEA Juneau Kirkwall ESTONIA Perm Labrador Sea Goteborg Yedrovo Kostroma Kirov Verkhnaya Salda Aldan BAY UNITED KINGDOM Aluksne Yaroslavl Nizhniy Tagil Aberdeen Alborg Riga Ivanovo SEA Kalinin Izhevsk Sverdlovsk Itatka Yoshkar Ola Tyumen NORTH LATVIA Teykovo Gladkaya Edinburgh DENMARK Shadrinsk Tomsk Copenhagen Moscow Gorky Kazan OF BALTIC SEA Cheboksary Krasnoyarsk Bratsk Glasgow LITHUANIA Uzhur SEA Esbjerg Malmo Kaunas Smolensk Kaliningrad Kurgan Novosibirsk Kemerovo Belfast Vilnius Chelyabinsk OKHOTSK Kolobrzeg RUSSIA Ulyanovsk Omsk Douglas Tula Ufa C AN Leeds Minsk Kozelsk Ryazan AD A Gdansk Novokuznetsk Manchester Hamburg Tolyatti Magnitogorsk Magdagachi Dublin Groningen Penza Barnaul Shefeld Bremen POLAND Edmonton Liverpool BELARU S Goose Bay NORTH Norwich Assen Berlin -

Gorilla Trekking Safari

BEST OF KENYA “12 – Day Wildlife Safari” UNE J 4 – 15, 2021 $4950 per person plus international airfare Single Supplement - $2250 Kenya is renowned for its unparalleled wildlife, habitat diversity and fascinating cultural heritage. A wide range of ecological zones, semi-arid plains and vast savannahs, tropical montane forests, rugged wilderness, acacia woodlands, and rugged wilderness, provide for a tremendous array of fauna and flora. Under a limitless sapphire sky thrives an animal population, staggering in both diversity and number. Here, elephant, zebra, leopard, lion, rhinoceros, giraffe, cheetah and baboon have lived and adapted for eons in this ancient landscape, alongside more than a thousand colorful bird species and a multitude of butterflies and other insects. Our safari combines superlative wildlife viewing with luxurious comfort and attentive service, while staying in some of Kenya’s finest safari lodges and tented camps, as we explore in depth, this magical land known as the “Gem of Africa.” SAFARI ITINERARY DAY 1 – JUNE 4 - DEPART USA DAY 2 – JUNE 5 - ARRIVE NAIROBI (NBO) Upon arrival at the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, you will be met by Safari Legacy and transferred to your hotel for check in. Overnight Crown Plaza Hotel. (meals in-flight) https://www.ihg.com/crowneplaza/hotels/us/en/nairobi/nbocp/hoteldetail DAY 3 – JUNE 6 - NAIROBI / TRAIN TO VOI / TSAVO WEST NATIONAL PARK & TAITA HILLS CONSERVANCY After breakfast, board your train and enjoy a scenic 4-hour train excursion to Voi Station where you will be met by your Safari Legacy Safari guides. Continue to the Taita Hills Conservancy arriving at Salt Lick Safari Lodge in time for lunch. -

Nowhere to Go : Informal Settlement Eradication in Kigali, Rwanda

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2017 Nowhere to go : informal settlement eradication in Kigali, Rwanda. Emily E Benken University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Benken, Emily E, "Nowhere to go : informal settlement eradication in Kigali, Rwanda." (2017). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 127. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/127 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOWHERE TO GO: INFORMAL SETTLEMENT ERADICATION IN KIGALI, RWANDA By Emily Elizabeth Benken Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude and for Graduation with Honors from the Department of Anthropology University of Louisville May 2017 i ii NOWHERE TO GO: INFORMAL SETTLEMENT ERADICATION IN KIGALI, RWANDA By Emily Elizabeth Benken A Thesis Approved on March 27th, 2017 by the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Advisor Thesis Committee Member Thesis Committee Member iii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my grandmother Mrs. Joyce Graeter Whose unending support made this thesis possible. -

Statement of Outcomes of the 6Th Africa Initiative Meeting 1St March 2019, Kigali, Rwanda

Statement of outcomes of the 6th Africa Initiative meeting 1st March 2019, Kigali, Rwanda 1. On 28 February – 1st March 2019, 68 delegates from 22 African countries and 11 Africa Initiative partners came together in Kigali, Rwanda, for the 6th meeting of the Africa Initiative (see annex 1). 2. The Africa Initiative was launched for a period of three years by the OECD hosted Global Forum in 2014 along with its African members and development partners (see annex 2). The Initiative aims to ensure that African countries can realise the full potential of progress made by the global community in implementing tax transparency and in international tax cooperation. With encouraging first results, its mandate was renewed for a further period of three years (2018-2020) in Yaoundé in November 2017. Countries participating in the Africa Initiative have committed to meeting specific and measurable targets in implementing and using the international tax transparency standards. 3. The delegates welcomed the attendance and support of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Central Africa Monetary and Economic Community (CEMAC), the East Africa Community (EAC), the Organisation for the harmonisation of business law in Africa (Organisation pour l’Harmonisation en Afrique du Droit des Affaires – OHADA) and the European Union for the first time at an Africa Initiative meeting. 4. Emphasising the increasing political focus on tackling illicit financial flows (IFFs) from Africa, delegates discussed how to convert political attention into tangible deliverables. They acknowledged that enhanced tax transparency is an important part of the solution to fighting tax evasion which in turn is a major component of IFFs. -

Occupational Health Impacts of Climate Change Across Different Climate Zones and Elevations in Sub-Saharan East Africa

Vol. 15(6), pp. 243-251, June 2021 DOI: 10.5897/AJEST2021.2976 Article Number: 71E736F67065 ISSN: 1996-0786 Copyright ©2021 African Journal of Environmental Science and Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJEST Technology Full Length Research Paper Occupational health impacts of climate change across different climate zones and elevations in sub-Saharan East Africa Samuel Kruse1*, Odilichi Ezenwanne2, Matthias Otto3, Tord Kjellstrom4, Patrick Remington5, Bruno Lemke3, Belay Simane6 and Jonathan A Patz7 1Department of Computer Sciences, School of Computer, Data & Information Sciences, University of Wisconsin - Madison, United States. 2Aaron E. Henry Community Health Services Center Inc. United States. 3Nelson Marlborough Institute of Technology, New Zealand. 4Health and Environment International Trust, New Zealand. 5School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin - Madison, United States. 6Center for Environment and Sustainable Development College of Development Studies Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. 7Global Health Institute of University of Wisconsin-Madison, United States. Received 3 January, 2021; Accepted 25 May, 2021 Climate change will cause Sub-Saharan tropical countries to experience a disproportionate increase in the number of extremely hot days when compared to Western countries with more temperate climates. We use the High Occupational Temperature Health and Productivity Suppression (HOTHAPS) model to estimate the potential impact of rising temperatures on worker productivity in different climate regions within Ethiopia, Uganda, Rwanda, and Kenya under varying future climate change scenarios. Using population data obtained from the International Labor Organization, we also estimate productivity losses at a country-wide level. We project large inter-country and intra-country disparities in productivity losses due to varying climatic conditions and local geography. -

The Obama Administration and the Struggles to Prevent Atrocities in the Central African Republic

POLICY PAPER November 2016 THE OBAMA ADMINISTRATION AUTHOR: AND THE STRUGGLE TO Charles J. Brown Leonard and Sophie Davis PREVENT ATROCITIES IN THE Genocide Prevention Fellow, January – June 2015. Brown is CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC currently Managing Director of Strategy for Humanity, LLC. DECEMBER 2012 – SEPTEMBER 2014 1 METHODOLOGY AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is the product of research conducted while I was the Leonard and Sophie Davis Genocide Prevention Fellow at the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). It is based on a review of more than 3,500 publicly available documents, including material produced by the US and French governments, the United Nations, the African Union, and the Economic Community of Central African States; press stories; NGO reports; and the Twitter and Facebook accounts of key individuals. I also interviewed a number of current and former US government officials and NGO representatives involved in the US response to the crisis. Almost all interviewees spoke on background in order to encourage a frank discussion of the relevant issues. Their views do not necessarily represent those of the agencies or NGOs for whom they work or worked – or of the United States Government. Although I attempted to meet with as many of the key players as possible, several officials turned down or did not respond to interview requests. I would like to thank USHMM staff, including Cameron Hudson, Naomi Kikoler, Elizabeth White, Lawrence Woocher, and Daniel Solomon, for their encouragement, advice, and comments. Special thanks to Becky Spencer and Mary Mennel, who were kind enough to make a lakeside cabin available for a writing retreat. -

Information Bulletin Africa: Multiple Disasters and Hazards

Information bulletin Africa: Multiple disasters and hazards This bulletin is being issued for information only and reflects the current situation and details available at this time. Respective National Societies, with the support of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), are working to respond to each of these disasters through different means. Some have DREFs or Emergency Appeals launched, and others may require additional support in the future. P a g e | 2 The situation and Red Cross and Red Crescent action Summary: Africa is facing several disasters and crises which are multi-faceted and overlapping. The most widely publicized of these is the COVID-19 pandemic. As of 17 May 2020, there were 51,842 confirmed cases in Africa, with 2,011 deaths reported.1 The actual numbers of people infected and who have died from the virus are likely to be much higher, due to lack of testing capacity in many countries and general under-reporting. The countries with the highest burden of confirmed cases are South Africa, Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon, Guinea, and Senegal, followed by Cote d’Ivoire, Sudan, Somalia and Djibouti. Health systems and infrastructure vary by countries and are not up to international standards in most of the countries , and also burdened by other diseases including HIV, malaria, cholera and Ebola. This means that the existing health system in most countries cannot handle the full effect of COVID- 19 pandemic. Long-running conflicts or protracted crises have exacerbated the impact of COVID-19, both in terms of health and economics, in some countries. -

Assessment and Evaluation of the Response of Vegetation Dynamics to Climate Variability in Africa

sustainability Article Assessment and Evaluation of the Response of Vegetation Dynamics to Climate Variability in Africa Vincent Nzabarinda 1,2,3 , Anming Bao 1,2, Wenqiang Xu 1,2,*, Solange Uwamahoro 1,2,3, Liangliang Jiang 4, Yongchao Duan 5, Lamek Nahayo 6 , Tao Yu 1,2,3, Ting Wang 1,2,3 and Gang Long 1,2,3 1 State Key Laboratory of Desert and Oasis Ecology, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China; [email protected] (V.N.); [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (S.U.); [email protected] (T.Y.); [email protected] (T.W.); [email protected] (G.L.) 2 Key Laboratory of GIS & RS Application Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Urumqi 830011, China 3 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 4 School of Geography and Tourism, Chongqing Normal University, Chongqing 401331, China; [email protected] 5 Binjiang College, Nanjing University of Information Engineering, Nanjing 210044, China; [email protected] 6 Faculty of Environmental Studies, University of Lay Adventists of Kigali, 6392 Kigali, Rwanda; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Understanding the impacts of climate variability and change on terrestrial ecosystems in Africa remains a critical issue for ecology as well as for regional and global climate policy mak- ing. However, acquiring this knowledge can be useful for future predictions towards improved governance for sustainable development. In this study, we analyzed the spatial–temporal charac- teristics of vegetation greenness, and identified the possible relationships with climatic factors and vulnerable plant species across Africa. -

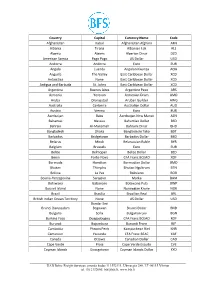

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Addendum to the Report of the Panel of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth of DR Congo

Addendum to the report of the Panel of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth of DR Congo S/2001/1072 Letter dated 10 November 2001 from the Secretary-General to the President of the Security Council I wish to refer to the presidential statement dated 3 May 2001 (S/PRST/2001/13), in which the Security Council extended the mandate of the Panel of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth of the Democratic Republic of the Congo for a final period of three months. I also wish to refer to the President's letter, by which the Panel's mandate was extended until 30 November 2001 (S/2001/951), and the Panel was requested to submit, through me, an addendum to its final report. I have the honour to transmit to you the addendum to the report of the Panel, submitted to me by the Chairperson of the Panel. I should be grateful if you would bring the report to the attention of the members of the Security Council. (Signed) Kofi A. Annan Addendum to the report of the Panel of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth of the Democratic Republic of the Congo 1 I. Introduction 1. By the statement of its President of 2 June 2000 (S/PRST/2000/20), the Security Council requested the Secretary-General to establish a Panel of Experts on the illegal exploitation of the natural resources and other forms of wealth of the Democratic Republic of the Congo with the following mandate: (a) To follow up on reports and collect information on all activities of illegal exploitation of natural resources and other forms of wealth of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, including in violation of the sovereignty of that country; (b) To research and analyse the links between the exploitation of the natural resources and other forms of wealth in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the continuation of the conflict.