Experiencing Hubble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

Eagle Nebula Star Formation Region

Eagle Nebula Star Formation Region AST 303: Chapter 17 1 The Formation of Stars (2) • A cloud of gas and dust must collapse if stars are to be formed. • The self-gravity of the cloud will tend to cause it to collapse. • Radiation pressure from nearby hot stars may do the same. • The passage of a shock wave from a nearby supernova blast or some other source (such as galactic shock waves) may do the same. – Note: The “sonic boom” of a jet plane is an example of a shock wave. • When two clouds collide, they may cause each other to collapse. AST 303: Chapter 17 2 Trifid Nebula AST 303: Chapter 17 3 Trifid Nebula Stellar Nursery Revealed AST 303: Chapter 17 4 Young Starburst Cluster Emerges from Cloud AST 303: Chapter 17 5 The Formation of Stars (3) • The gas in the collapsing cloud probably becomes turbulent. • This would tend to fragment the collapsing gas, producing condensations that would be the nuclei of new stars. • There is abundant evidence that shows that the stars in a cluster are all about the same age. For a young cluster, many stars have not yet reached the main sequence: ! Isochron Luminosity "Temperature AST 303: Chapter 17 6 The Formation of Stars (4) • The evolutionary paths of young stars on the H-R diagram look like this. Note the T Tauri stars, long thought to be young stars. • Theory says that these stars use convection as the main method of transporting energy to their surfaces. ! T Tauri Stars Luminosity "Temperature AST 303: Chapter 17 7 The Search for Stellar Precursors • Astronomers have long been fascinated by very dark, dense regions seen outlined against bright gas, called globules. -

The Messier Catalog

The Messier Catalog Messier 1 Messier 2 Messier 3 Messier 4 Messier 5 Crab Nebula globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 6 Messier 7 Messier 8 Messier 9 Messier 10 open cluster open cluster Lagoon Nebula globular cluster globular cluster Butterfly Cluster Ptolemy's Cluster Messier 11 Messier 12 Messier 13 Messier 14 Messier 15 Wild Duck Cluster globular cluster Hercules glob luster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 16 Messier 17 Messier 18 Messier 19 Messier 20 Eagle Nebula The Omega, Swan, open cluster globular cluster Trifid Nebula or Horseshoe Nebula Messier 21 Messier 22 Messier 23 Messier 24 Messier 25 open cluster globular cluster open cluster Milky Way Patch open cluster Messier 26 Messier 27 Messier 28 Messier 29 Messier 30 open cluster Dumbbell Nebula globular cluster open cluster globular cluster Messier 31 Messier 32 Messier 33 Messier 34 Messier 35 Andromeda dwarf Andromeda Galaxy Triangulum Galaxy open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy Messier 36 Messier 37 Messier 38 Messier 39 Messier 40 open cluster open cluster open cluster open cluster double star Winecke 4 Messier 41 Messier 42/43 Messier 44 Messier 45 Messier 46 open cluster Orion Nebula Praesepe Pleiades open cluster Beehive Cluster Suburu Messier 47 Messier 48 Messier 49 Messier 50 Messier 51 open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy open cluster Whirlpool Galaxy Messier 52 Messier 53 Messier 54 Messier 55 Messier 56 open cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 57 Messier -

00E the Construction of the Universe Symphony

The basic construction of the Universe Symphony. There are 30 asterisms (Suites) in the Universe Symphony. I divided the asterisms into 15 groups. The asterisms in the same group, lay close to each other. Asterisms!! in Constellation!Stars!Objects nearby 01 The W!!!Cassiopeia!!Segin !!!!!!!Ruchbah !!!!!!!Marj !!!!!!!Schedar !!!!!!!Caph !!!!!!!!!Sailboat Cluster !!!!!!!!!Gamma Cassiopeia Nebula !!!!!!!!!NGC 129 !!!!!!!!!M 103 !!!!!!!!!NGC 637 !!!!!!!!!NGC 654 !!!!!!!!!NGC 659 !!!!!!!!!PacMan Nebula !!!!!!!!!Owl Cluster !!!!!!!!!NGC 663 Asterisms!! in Constellation!Stars!!Objects nearby 02 Northern Fly!!Aries!!!41 Arietis !!!!!!!39 Arietis!!! !!!!!!!35 Arietis !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1056 02 Whale’s Head!!Cetus!! ! Menkar !!!!!!!Lambda Ceti! !!!!!!!Mu Ceti !!!!!!!Xi2 Ceti !!!!!!!Kaffalijidhma !!!!!!!!!!IC 302 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 990 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1024 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1026 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1070 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1085 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1107 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1137 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1143 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1144 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1153 Asterisms!! in Constellation Stars!!Objects nearby 03 Hyades!!!Taurus! Aldebaran !!!!!! Theta 2 Tauri !!!!!! Gamma Tauri !!!!!! Delta 1 Tauri !!!!!! Epsilon Tauri !!!!!!!!!Struve’s Lost Nebula !!!!!!!!!Hind’s Variable Nebula !!!!!!!!!IC 374 03 Kids!!!Auriga! Almaaz !!!!!! Hoedus II !!!!!! Hoedus I !!!!!!!!!The Kite Cluster !!!!!!!!!IC 397 03 Pleiades!! ! Taurus! Pleione (Seven Sisters)!! ! ! Atlas !!!!!! Alcyone !!!!!! Merope !!!!!! Electra !!!!!! Celaeno !!!!!! Taygeta !!!!!! Asterope !!!!!! Maia !!!!!!!!!Maia Nebula !!!!!!!!!Merope Nebula !!!!!!!!!Merope -

Just What Are Those Sky Chart "M" and "NGC" Numbers? by Barry D

Just what are those Sky Chart "M" and "NGC" Numbers? By Barry D. Malpas – Special to the Williams-Grand Canyon News – 2014 November One of the pastimes for some early sky observers was to locate new comets. Charles Messier (1730-1817) was a French comet hunter during the late 1700s, and discovered 13 new comets between 1760 and 1785. His interest in astronomy, and comets in particular, was influenced by seeing the great comet of 1744, and the comet of 1759 (of which Edmond Halley had believed the comets of 1531, 1607, and 1682 were the same and had predicted the comet’s 1759 apparition which is now known as Halley's Comet.) At this time telescopes were relatively small. The understanding of supernovae, or galaxies, was not yet in the current knowledge, as such objects only appeared as blurry smudges that did not move across the sky. In order not to waste time and become frustrated with viewing fuzzy objects that resembled, but were not, comets, Messier compiled a list of 110 of these celestial blurs which we now refer to as Messier, or "M Objects." The Messier Catalog has become a very popular list of "Deep Sky Objects" among amateur astronomers around the world because it consists of most of the galaxies, nebulae and star clusters easily observable with binoculars or small telescopes in the northern skies. Now, however, the objects in the list are the source of interest, as opposed to the reason the compilation was originally intended by Messier. At large astronomical get-togethers, known as "star parties", there is often a "Messier Marathon" competition to view the most Messier Objects during one observing night. -

Activity 3: Nebulas - 1 Where Stars Are Born

Day 2: Stars and constellations Activity 3: Nebulas - 1 Where Stars Are Born Introduction A nebula is an interstellar cloud of dust and gas. Some nebulas are called “star nurseries” because that’s where stars are formed, or "born." Our own Sun was born 4.6 billion years ago! Supplies (for each child) • Clear glass jar with a lid • Plastic spoon • Water • Tempera paint (at least 2 colors, blues, purples, and pinks work well) • Glitter • Cotton balls (about 18 per child, depending on the size of the jar) Get kids thinking In this activity, kids will create a model of a nebula. A nebula looks like a big cloud of dust and gas located in interstellar space. They are very far away — the closest one to Earth is called the Helix Nebula and it is 700 light years away. That means even if you could travel at the speed of light, it would take you 700 years to get there! Ask kids: If nebulas are so far away, how do we know what they look like? Astronomers use very powerful space telescopes, such as the Hubble telescope, to take pictures of nebulas. Share photographs of the Helix Nebula and the Orion Nebula (see pages 17-18). If you have access to the Internet, watch this video from NASA, Flight Through the Orion Nebula. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/take-trip-through-orion-nebula-nasas-awe- some-video-1-180967825/ 16 Day 2: Stars and constellations Activity 3: Nebulas - 1 Where Stars Are Born Helix Nebula 17 Day 2: Stars and constellations Activity 3: Nebulas - 1 Where Stars Are Born Orion Nebula On a clear night, if you look at the constellation Orion, you might get a glimpse of a star nursery. -

The Angular Size of Objects in the Sky

APPENDIX 1 The Angular Size of Objects in the Sky We measure the size of objects in the sky in terms of degrees. The angular diameter of the Sun or the Moon is close to half a degree. There are 60 minutes (of arc) to one degree (of arc), and 60 seconds (of arc) to one minute (of arc). Instead of including – of arc – we normally just use degrees, minutes and seconds. 1 degree = 60 minutes. 1 minute = 60 seconds. 1 degree = 3,600 seconds. This tells us that the Rosette nebula, which measures 80 minutes by 60 minutes, is a big object, since the diameter of the full Moon is only 30 minutes (or half a degree). It is clearly very useful to know, by looking it up beforehand, what the angular size of the objects you want to image are. If your field of view is too different from the object size, either much bigger, or much smaller, then the final image is not going to look very impressive. For example, if you are using a Sky 90 with SXVF-M25C camera with a 3.33 by 2.22 degree field of view, it would not be a good idea to expect impressive results if you image the Sombrero galaxy. The Sombrero galaxy measures 8.7 by 3.5 minutes and would appear as a bright, but very small patch of light in the centre of your frame. Similarly, if you were imaging at f#6.3 with the Nexstar 11 GPS scope and the SXVF-H9C colour camera, your field of view would be around 17.3 by 13 minutes, NGC7000 would not be the best target. -

The Messier Marathon Search Sequence

2/28/2020 Messier Marathon Search Sequence List This file presents the Messier objects in the order of the Marathon Search Sequence given by Don Machholz in his Messier Marathon Observer's Guide. The Messier Marathon Search Sequence compiled online by Hartmut Frommert, using work of Don Machholz. Depending on geographic location, it may be impossible to find them all, and may be better to slightly modify this list. In case of doubt consult Don Machholz's book. This list should be good for northern latitudes 20 to 40. 1. M77 spiral galaxy in Cetus 2. M74 spiral galaxy in Pisces 3. M33 The Triangulum Galaxy (also Pinwheel) spiral galaxy in Triangulum 4. M31 The Andromeda Galaxy spiral galaxy in Andromeda 5. M32 Satellite galaxy of M31 elliptical galaxy in Andromeda 6. M110 Satellite galaxy of M31 elliptical galaxy in Andromeda 7. M52 open cluster in Cassiopeia 8. M103 open cluster in Cassiopeia 9. M76 The Little Dumbell, Cork, or Butterfly planetary nebula in Perseus 10. M34 open cluster in Perseus 11. M45 Subaru, the Pleiades--the Seven Sisters open cluster in Taurus 12. M79 globular cluster in Lepus 13. M42 The Great Orion Nebula diffuse nebula in Orion 14. M43 part of the Orion Nebula (de Mairan's Nebula) diffuse nebula in Orion 15. M78 diffuse reflection nebula in Orion 16. M1 The Crab Nebula supernova remnant in Taurus 17. M35 open cluster in Gemini 18. M37 open cluster in Auriga 19. M36 open cluster in Auriga 20. M38 open cluster in Auriga 21. M41 open cluster in Canis Major 22. -

Astrophotography?

Digitizing the Universe From Your Backyard Robert J. Vanderbei 2008 February 27 http://www.princeton.edu/∼rvdb Why Astrophotography? Long Exposures, Permanent Record, Digital Enhancement, Light Pollution! Visual Experience Long Exposure Light Pollution Subtracted Some Pictures 1. Crab Nebula 2. Lagoon Nebula 3. Hercules Globular Cluster 4. Swan Nebula 5. Dumbbell Nebula 6. Orion Nebula 7. Orion Nebula|Close Up 8. M82 and M81 9. Running Man Nebula 10. Rosette Nebula 11. Rosette Nebula—Widefield 12. Rosette Nebula|Driveway vs. Mt. Palomar Driveway Mt. Palomar (48-inch) 13. Pleiades Equipment In order of IMPORTANCE... 1. Mount 2. Camera Computer Software 3. Telescope (OTA) NOTE: This talk is about deep sky astrophotography. For imaging the moon and the planets, the order would be reversed. Astronomical CCD camera • Pixel size: 6:45 × 6:45 microns • Pixels: 1392 x 1040 • Quant. Eff.: ∼ 65% • Readout Noise: ∼ 7 electrons • Cooling: ∼ 30◦C below ambient • Download: 3:5 seconds • Format: 16 bit • Weight: 350g Example \Telescope": 200mm f/3.5 Vivitar lens ($30) Mount: Questar Camera: Starlight Express SXV-H9 Filter: Dichroic Hα Fundamental Principles • Focal length determines field of view • F-ratio determines exposure time Total exposure time = 156 mins. Field of view = 2:5◦. Combatting Light Pollution Narrow-Band Filters Visual Astronomy vs. Astrophotography • Aperture determines photon flux • Focal length determines field of view • F-ratio determines exposure time Image Acquisition 1. Move equipment outside (3 minutes). Let cool (in parallel). 2. Polar align (2 minutes). 3. Manually point at a known star (1 minute). 4. Fire up MaximDL, my image acquisition software (0 minutes). -

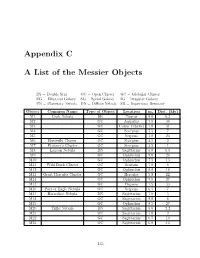

Appendix C a List of the Messier Objects

Appendix C A List of the Messier Objects DS=DoubleStar OC=OpenCluster GC=GlobularCluster EG = Elliptical Galaxy SG = Spiral Galaxy IG = Irregular Galaxy PN = Planetary Nebula DN = Diffuse Nebula SR = Supernova Remnant Object Common Name Type of Object Location mv Dist. (kly) M1 Crab Nebula SR Taurus 9.0 6.3 M2 GC Aquarius 7.5 36 M3 GC Canes Venatici 7.0 31 M4 GC Scorpius 7.5 7 M5 GC Serpens 7.0 23 M6 Butterfly Cluster OC Scorpius 4.5 2 M7 Ptolemy’s Cluster OC Scorpius 3.5 1 M8 Lagoon Nebula DN Sagittarius 5.0 6.5 M9 GC Ophiuchus 9.0 26 M10 GC Ophiuchus 7.5 13 M11 Wild Duck Cluster OC Scutum 7.0 6 M12 GC Ophiuchus 8.0 18 M13 Great Hercules Cluster GC Hercules 5.8 22 M14 GC Ophiuchus 9.5 27 M15 GC Pegasus 7.5 33 M16 Part of Eagle Nebula OC Serpens 6.5 7 M17 Horseshoe Nebula DN Sagittarius 7.0 5 M18 OC Sagittarius 8.0 6 M19 GC Ophiuchus 8.5 27 M20 Trifid Nebula DN Sagittarius 5.0 2.2 M21 OC Sagittarius 7.0 3 M22 GC Sagittarius 6.5 10 M23 OC Sagittarius 6.0 4.5 135 Object Common Name Type of Object Location mv Dist. (kly) M24 Milky Way Patch Star cloud Sagittarius 11.5 10 M25 OC Sagittarius 4.9 2 M26 OC Scutum 9.5 5 M27 Dumbbell Nebula PN Vulpecula 7.5 1.25 M28 GC Sagittarius 8.5 18 M29 OC Cygnus 9.0 7.2 M30 GC Capricornus 8.5 25 M31 Andromeda Galaxy SG Andromeda 3.5 2500 M32 Satellite galaxy of M31 EG Andromeda 10.0 2900 M33 Triangulum Galaxy SG Triangulum 7.0 2590 M34 OC Perseus 6.0 1.4 M35 OC Gemini 5.5 2.8 M36 OC Auriga 6.5 4.1 M37 OC Auriga 6.0 4.6 M38 OC Auriga 7.0 4.2 M39 OC Cygnus 5.5 0.3 M40 Winnecke 4 DS Ursa Major 9.0 M41 OC Canis -

The Hot and Dusty Instellar Medium Through X-Ray Spectroscopy D

The Hot and Dusty Instellar Medium through X-Ray Spectroscopy D. Rogantini Summary The interstellar medium is an enormous painting consisting of strong strokes of gas and dust which fill interstellar space and shades smoothly into the surrounding intergalactic canvas. Despite the extremely low particle density, on average lower than the vacuum in laboratories, from the interstellar medium, spectacular structures can arises which can be greatly different in temperature, density, composition and size. These define the patchy structure of the Milky Way, our home-galaxy. The interstellar gas is primarily composed of hydrogen and helium. All the other elements (like carbon, oxygen, iron, magnesium), indicated as metals in astronomy, represent less than 2% of the total mass. Despite this small fraction, the metals have an important role in the chemical and physical processes of the Galaxy. The interstellar medium is usually divided in three phases (cold, warm and hot phases) distinguished by the temperature and density of the gas. Cool and dense regions of the interstellar medium, contain most of the interstellar matter and they occupy less than 5% of the Galactic volume. The material is principally concentrated into giant clouds, known as molecular clouds, where molecular hydrogen coexists with neutral gas and interstellar dust. This cold medium is embedded in a hot buoyant medium (known as hot coronal gas) which occupies most of the volume of interstellar space and extends to the Galactic halo. In this floating and rarefied medium, matter is primarily ionised and heated by powerful shocks from stellar winds or supernova explosions. The space between the cold and hot phases is occupied by an extended intercloud medium, consisting of neutral and low ionised gas. -

Cold Dark Clouds: the Initial Conditions for Star Formation

ANRV320-AA45-09 ARI 12 May 2007 15:39 V I E E W R S First published online as a Review in Advance on May 21, 2007 I E N C N A D V A Cold Dark Clouds: The Initial Conditions for Star Formation Edwin A. Bergin1 and Mario Tafalla2 1Department of Astronomy, University of Michigan, Michigan, 48109; email: [email protected] 2Observatorio Astronomico´ Nacional, E-28014 Madrid, Spain; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2007. 45:339–96 Key Words The Annual Review of Astrophysics is online at interstellar medium, interstellar molecules, molecular clouds, astro.annualreviews.org prestellar cores, star formation This article’s doi: 10.1146/annurev.astro.45.071206.100404 Abstract Copyright c 2007 by Annual Reviews. Cold dark clouds are nearby members of the densest and coldest All rights reserved phase in the Galactic interstellar medium, and represent the most 0066-4146/07/0922-0339$20.00 accessible sites where stars like our Sun are currently being born. In by University of California - Berkeley on 07/26/07. For personal use only. this review we discuss recent progress in their study, including the newly discovered IR dark clouds that are likely precursors to stellar Annu. Rev. Astro. Astrophys. 2007.45. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org clusters. At large scales, dark clouds present filamentary mass distri- butions with motions dominated by supersonic turbulence. At small, subparsec scales, a population of subsonic starless cores provides a unique glimpse of the conditions prior to stellar birth. Recent studies of starless cores reveal a combination of simple physical properties together with a complex chemical structure dominated by the freeze- out of molecules onto cold dust grains.