Final Copy 2019 10 01 Hutch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton FACULTY OF jAJFlTlS AM) SOCIAL SCIENCES School of History Mary Carpenter: Her Father s Daughter? by Susy Brigden 0 Mary Carpenter Frontispiece to 7%e oW Mo/y Cwpemfer by J. Estlin Carpenter, 1879. Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2011 ABSTRACT This thesis consists of four thematic chapters showing Mary Carpenter (1808-1877) as an example of a Unitarian educational reformer who carved for herself a respectable public life at a time when the emphasis was on separate spheres for women. Mary's significance has recently become more widely broadcast, although her place as a leading pedagogue in educational history still needs to be asserted. -

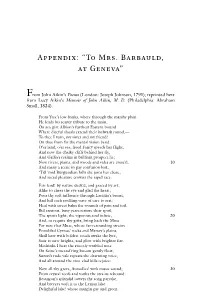

Appendix: “To Mrs. Barbauld, at Geneva”

Appendix: “To Mrs. Barbauld, at Geneva” From John Aikin’s Poems (London: Joseph Johnson, 1791); reprinted here from Lucy Aikin’s Memoir of John Aikin, M. D. (Philadelphia: Abraham Small, 1824). From Yare’s low banks, where through the marshy plain He leads his scanty tribute to the main, On sea-girt Albion’s furthest Eastern bound Where direful shoals extend their bulwark round,— To thee I turn, my sister and my friend! On thee from far the mental vision bend. O’er land, o’er sea, freed Fancy speeds her flight, And now the chalky cliffs behind her fly, And Gallia’s realms in brilliant prospect lie; Now rivers, plains, and woods and vales are cross’d, 10 And many a scene in gay confusion lost, ’Till ’mid Burgundian hills she joins her chase, And social pleasure crowns the rapid race. Fair land! by nature deck’d, and graced by art, Alike to cheer the eye and glad the heart, Pour thy soft influence through Laetitia’s breast, And lull each swelling wave of care to rest; Heal with sweet balm the wounds of pain and toil, Bid anxious, busy years restore their spoil; The spirits light, the vigorous soul infuse, 20 And, to requite thy gifts, bring back the Muse. For sure that Muse, whose far-resounding strains Ennobled Cyrnus’ rocks and Mersey’s plains, Shall here with boldest touch awake the lyre, Soar to new heights, and glow with brighter fire. Methinks I hear the sweetly-warbled note On Seine’s meand’ring bosom gently float; Suzon’s rude vale repeats the charming voice, And all around the vine-clad hills rejoice: Now all thy grots, Auxcelles! with music sound; 30 From crystal roofs and vaults the strains rebound: Besançon’s splendid towers the song partake, And breezes waft it to the Leman lake. -

The Language of the Southey-Coleridge Circle

Pratt, Lynda & David Denison. 2000. The language of the Southey-Coleridge circle. Language Sciences 22.3, 401-22. http://www.journals.elsevier.com/language-sciences/ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0388000100000139 THE LANGUAGE OF THE SOUTHEY-COLERIDGE CIRCLE 1 LYNDA PRATT and DAVID DENISON In this joint paper the Southey-Coleridge circle is looked at from two points of view. The first part of the paper, written by Pratt, employs a literary-historical approach in order to establish the boundaries of the network and to explore its complex social and textual dynamics. Concentrating on both the public and private identities of the Southey-Coleridge circle, it reveals the complex nature of literary and political culture in the closing years of the eighteenth century. The second part, written by Denison, examines a linguistic innovation, the progressive passive, and relates it to usage by members of the circle acting as a social network. A brief conclusion draws both parts together. The Southey-Coleridge Circle in the 1790s In his 1802 appraisal of the Oriental romance Thalaba the Destroyer (1801), Francis Jeffrey, one of the leading lights of the recently founded Edinburgh Review , identified a ‘sect of poets’ who were all ‘dissenters from the established systems in poetry and criticism’ and whose writings were fuelled by a ‘splenetic and idle discontent with the existing institutions of society’ ( Edinburgh Review 1 (October 1802), quoted in Madden, 1972: 68, 76). This group included Robert Southey, the author of Thalaba , Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth. 2 It was a sect which early nineteenth-century contemporaries and critics were 1 We are grateful to Grevel Lindop for helpful encouragement, and to Sylvia Adamson for numerous cogent promptings towards clarity. -

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

/ I o?V SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE A NARRATIVE OF THE EVENTS OF HIS LIFE BY JAMES DYKES CAMPBELL ILonDon MACMILLAN AND CO. AND NEW YORK 1894 bin ; C3:>' PREFACE This Memoir is mainly a reproduction of the bio- graphical sketch prefixed to the one-volume edition of Coleridge's Poetical Works^ published last spring. Such an Introduction generally and properly consists of a brief summary of some authoritative biography. As, however, no authoritative biography of Coleridge existed, I was obliged to construct a narrative for my own purpose. With this view, I carefully sifted all the old printed biographical materials, and as far as possible collated them with the original documents I searched all books of Memoirs, etc., likely to Coleridge contain incidental information regarding ; and, further, I was privileged by being permitted to make use of much important matter, either absolutely new, or previously unavailable. My aim had been, not to add to the ever- lengthening array of estimates of Coleridge as a poet and philosopher, but to provide something 1 The Poetical Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Edited, with a Bio- graphical Introduction, by James Dykes Campbell. London : Macmillan and Co. 1893. SAMUEL TA YLOR COLERIDGE which appeared to be wanting—a plain, and as far as possible, an accurate narrative of the events of his life ; something which might serve until the appearance of the full biography which is expected from the hands of the poet's grandson, Mr. Ernest Hartley Coleridge. In preparing the present reprint of the ' Bio- graphical Introduction ' I have spared no effort towards making it worthy of separate publication, and of its new title. -

Joseph Priestley and the Intellectual Culture of Rational Dissent, 1752

Joseph Priestley and the Intellectual Culture of Rational Dissent, 1752-1796 Simon Mills Department of English, Queen Mary, University of London A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 2009 I confirm that this is my own work and that the use of material from other sources has been fully acknowledged. 2 Abstract Joseph Priestley and the Intellectual Culture of Rational Dissent, 1752-1796 Recent scholarship on the eighteenth-century polymath Joseph Priestley (1733-1804) has focused on his work as a pioneering scientist, a controversial Unitarian polemicist, and a radical political theorist. This thesis provides an extensive analysis of his comparatively neglected philosophical writings. It situates Priestley’s philosophy in the theological context of eighteenth-century rational dissent, and argues that his ideas on ethics, materialism, and determinism came to provide a philosophical foundation for the Socinian theology which came to prominence among Presbyterian congregations in the last decades of the century. Throughout the thesis I stress the importance of rational debate to the development of Priestley’s ideas. The chapters are thus structured around a series of Priestley’s engagements with contemporary figures: chapter 1 traces his intellectual development in the context of the debates over moral philosophy and the freedom of the will at the Daventry and Warrington dissenting academies; chapter 2 examines his response to the Scottish ‘common sense’ philosophers, Thomas Reid, James Beattie, and James Oswald; chapter 3 examines his writings on materialism and philosophical necessity and his debates with Richard Price, John Palmer, Benjamin Dawson, and Joseph Berington; chapter 4 focuses on his attempt to develop a rational defence of Christianity in opposition to the ideas of David Hume; chapter 5 traces the diffusion of his ideas through the syllabuses at the liberal dissenting academies at Warrington, Daventry, and New College, Hackney. -

Ministers in Cheshire Until 1896

Ministers in Cheshire until 1896 MANCHESTER : ZT. RAWSON AND CO., PRINTERS, 16, NEW BROWN STREE- I 896. I,'(1. ,.G List of Contractions ... ... .. Lists of Non-Parochial Registers and Records c ... Assembly of Lancashire and Cheshire .. way] fills ' the labour, c,. c,. -R' Q. z.. L.. 1- .. ,. .,c>++ ,: ,: ' , - 2;;. A g;,;;;'-.,. .*. .. S. g,?.<,' ;., . ' .,- g; ,. ' ;-.L . , &!;;:>!? ; 'I-?-,,; - +:+.S, . - !:. !:. 4' ,,. , *-% C v: c : &*:.S.; . h z iv. CORRIGENDA, 7 Dict. Nat. Biog. .. " The Dictionary of National Biography." Foster's Alumni Oxon.. " Alumni Oxonienses, 1500-1886"; . Joseph Foster, M.X. 8 vols. London, 1887-1892. Heywood's Register .. See " Northowram Register." M . , .. .. Congregationalism in Yorkshire"; James G[oodeve] Miall. Lon- don, 1868. ... " The Manchester Socinian Con- troversy." London, 1825. " A History of the Presbyterian and General Baptist Churches in the West of England " ; Jerom Murch. London, 1835. .. " Lancashire Nonconformity " ; B[enjamin] Nightingale. 6 vols. Manchester [18gr-18931. CORRIGENDA, Northowram Register.. " The Nonconformist Register of Baptisms, Marriages, and Deaths, . con~piledby the Revs. Oliver Heywood and T. Dickenson, ,. Atherton. Harry Toulmin. For d. 1833, read 1823. 1644-1 702, 1702-1752, gener- ally known as the Northowram p. 26. Burnley, line 3. For C. F., April, 1874, read April, 1871, p. 57. or Coley Register . ." ; edited by J. Hxsfall Turner. Brig- p. 45. Croft, line 3. For 1838, read 1839. house, 1881. Roll of Students Roll of Students," entered at p. 50. Dukinfield, line 5. For p. 729, read pp. 22, 681. Manchester Academy, 1786- 1803; Manchester College,York, p. 124. Platt, line 2. For Fulwood, nr. Bristol, read Fulwood, Yorks. 1803-1840 ; Manchester New College, Manchester, 1840- p. -

Issue 121 (Jan 2003)

The Charles Lamb Bulletin The Journal of the Charles Lamb Society January 2003 New Series No. 121 Contents Articles TIMOTHY WHELAN: “I have confessed myself a devil”: Crabb Robinson’s Confrontation with Robert Hall, 1798-1800 2 MARY R. WEDD: Romantic Presentations of the Lake District: The Lake District of The Prelude Book IV 26 Reviews TIMOTHY ZIEGENHAGEN on The Lab’ring Muses: Work, Writing, and the Social Order in English Plebeian Poetry, 1730-1830 by William J. Christmas 43 Society Notes and News from Members 46 2 “I have confessed myself a devil”: Crabb Robinson’s Confrontation with Robert Hall, 1798-1800 By TIMOTHY WHELAN I ON 26 MAY 1811, HENRY CRABB ROBINSON traveled across the Thames to the Borough to hear the celebrated Baptist minister Robert Hall. Hall’s sermon, Robinson says in his Diary, “was certainly a very beautiful one. He began by a florid but eloquent and impressive description of John the Baptist, and deduced from his history, not with the severity of argument which a logician requires, but with a facility of illustration which oratory delights in, and which was perfectly allowable, the practical importance of discharging the duty which belongs to our actual condition.”1 The fact that Robinson considered Hall’s sermon a “beautiful” discourse is not surprising. For years, Hall had been held in the highest rank of speakers, the “facile princips of English descent” who “outstripped all his contemporaries,” the Scottish critic George Gilfillan contended in 1846.2 F.A. Cox wrote in the North British Review that had Hall been a Parliamentarian, he would have “displayed in felicitous combination much of the splendor of Burke, the wit of Sheridan, the flow of Chatham and of Pitt, and the eloquence of Fox.”3 Comparing Hall with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Fox asserted that “Coleridge was more to be heard; Hall to be remembered. -

Coleridge and the Unitarian Ladies Felicity James

From The Coleridge Bulletin The Journal of the Friends of Coleridge New Series 28 (NS) Winter 2006 © 2006 Contributor all rights reserved http://www.friendsofcoleridge.com/Coleridge-Bulletin.htm Coleridge and the Unitarian Ladies Felicity James ____________________________________________________________________________________________ WANT TO START with a well-known exclamation of frustration from I Coleridge’s notebook: ‘Socinianism Moonlight—Methodism &c A Stove! O for some Sun that shall unite Light & Warmth’.1 That exclamation, first written in 1799 and retranscribed in notebook 21 in 1802, has often been taken as representative of his difficulties with the chilly rationalism of Unitarian thought, and with what Peter Kitson has termed ‘the weaknesses and dangers of… propertied dissenting belief’.2 But the neatness of that ‘Socinianism Moonlight’ formulation encourages us to ignore the ‘Light and Warmth’, the valuable encouragement, that the Unitarian community did offer Coleridge in the 1790s. My focus today is not on Coleridge’s changing attitudes toward Socinian theology: instead, I’d like to go some way toward more fully contextualising Coleridge’s Unitarian relationships, and to show how sociability, friendship, and domestic affection were a crucial part of his attraction toward Unitarianism. In particular, I focus on Coleridge’s relationship with two Unitarian ladies: Elizabeth Evans, part of the Strutt family of Derbyshire, and Anna Letitia Barbauld. Both women encouraged the young Coleridge in different ways—one practical, -

The Natural Philosophy of Samuel Taylor Coleridge

THE NATURAL PHILOSOPHY OF SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE by Janusz Aleksander Sysak Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. March 2000. Department of History and Philosophy of Science, The University of Melbourne. p.2 ABSTRACT This thesis aims to show that Coleridge's thinking about science was inseparable from and influenced by his social and political concerns. During his lifetime, science was undergoing a major transition from mechanistic to dynamical modes of explanation. Coleridge's views on natural philosophy reflect this change. As a young man, in the mid-1790s, he embraced the mechanistic philosophy of Necessitarianism, especially in his psychology. In the early 1800s, however, he began to condemn the ideas to which he had previously been attracted. While there were technical, philosophical and religious reasons for this turnabout, there were also major political ones. For he repeatedly complained that the prevailing 'mechanical philosophy' of the period bolstered emerging liberal and Utilitarian philosophies based ultimately on self-interest. To combat the 'commercial' ideology of early nineteenth century Britain, he accordingly advocated an alternative, 'dynamic' view of nature, derived from German Idealism. I argue that Coleridge championed this 'dynamic philosophy' because it sustained his own conservative politics, grounded ultimately on the view that states possess an intrinsic unity, so are not the product of individualistic self-interest. p.3 This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work; (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used; (iii) the thesis is less than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies, appendices and footnotes. -

Interpreting the Monsters of English Children's Literature

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses (De)monstration: Interpreting the monsters of English children's literature. Padley, Jonathan How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Padley, Jonathan (2006) (De)monstration: Interpreting the monsters of English children's literature.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42979 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ (DEMONSTRATION: INTERPRETING THE MONSTERS OF ENGLISH CHILDREN’S LITERATURE Jonathan Padley Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Wales Swansea January 2006 ProQuest Number: 10821369 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted.