The Fate of Stocked Barrens Topminnows Fundulus Julisia (Fundulidae) and Status of Wild Populations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Funding (Total $2,552,481) $15,000 2019

CURRICULUM VITAE TENNESSEE AQUARIUM CONSERVATION INSTITUTE 175 BAYLOR SCHOOL RD CHATTANOOGA, TN 37405 RESEARCH FUNDING (TOTAL $2,552,481) $15,000 2019. Global Wildlife Conservation. Rediscovering the critically endangered Syr-Darya Shovelnose Sturgeon. $10,000 2019. Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. Propagation of the Common Logperch as a host for endangered mussel larvae. $8,420 2019. Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. Monitoring for the Laurel Dace. $4,417 2019. Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. Examining interactions between Laurel Dace (Chrosomus saylori) and sunfish $12,670 2019. Trout Unlimited. Southern Appalachian Brook Trout propagation for reintroduction to Shell Creek. $106,851 2019. Private Donation. Microplastic accumulation in fishes of the southeast. $1,471. 2019. AZFA-Clark Waldram Conservation Grant. Mayfly propagation for captive propagation programs. $20,000. 2019. Tennessee Valley Authority. Assessment of genetic diversity within Blotchside Logperch. $25,000. 2019. Riverview Foundation. Launching Hidden Rivers in the Southeast. $11,170. 2018. Trout Unlimited. Propagation of Southern Appalachian Brook Trout for Supplemental Reintroduction. $1,471. 2018. AZFA Clark Waldram Conservation Grant. Climate Change Impacts on Headwater Stream Vertebrates in Southeastern United States $1,000. 2018. Hamilton County Health Department. Step 1 Teaching Garden Grants for Sequoyah School Garden. $41,000. 2018. Riverview Foundation. River Teachers: Workshops for Educators. $1,000. 2018. Tennessee Valley Authority. Youth Freshwater Summit $20,000. 2017. Tennessee Valley Authority. Lake Sturgeon Propagation. $7,500 2017. Trout Unlimited. Brook Trout Propagation. $24,783. 2017. Tennessee Wildlife Resource Agency. Assessment of Percina macrocephala and Etheostoma cinereum populations within the Duck River Basin. $35,000. 2017. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Status surveys for conservation status of Ashy (Etheostoma cinereum) and Redlips (Etheostoma maydeni) Darters. -

Endangered Species Listing Deadline Complaint

Case 1:16-cv-00503 Document 1 Filed 03/16/16 Page 1 of 25 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, ) 378 North Main Avenue ) Tucson, AZ 85701, ) Civil No: 16-00503 ) Plaintiff, ) COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY ) AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF v. ) ) SALLY M.R. JEWELL, Secretary of the ) Interior, U.S. Department of the Interior ) 1849 C Street NW ) Washington, DC 20240, ) ) and ) ) U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE, ) 1849 C Street NW ) Washington, DC 20240, ) ) Defendants. ) ______________________________________ ) INTRODUCTION 1. Plaintiff Center for Biological Diversity (“Center”) brings this action under the Endangered Species Act, 16 U.S.C. §§ 1531-1544 (“ESA”), to challenge the Secretary of the Interior’s (“Secretary”) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (“FWS”) (collectively, “Defendants” or “FWS”) failure to make mandatory findings on whether nine highly-imperiled species should be listed as threatened or endangered under the ESA. 16 U.S.C. § 1533(b)(3)(B). These species are: alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii), Barrens topminnow (Fundulus julisia), beaverpond marstonia (Marstonia castor), California spotted owl (Strix occidentalis occidentalis), Canoe Creek pigtoe (Pleurobema athearni), foothill yellow-legged frog (Rana boylii), Northern Rockies fisher (Martes pennanti), Virgin River spinedace Case 1:16-cv-00503 Document 1 Filed 03/16/16 Page 2 of 25 (Lepidomeda mollispinis mollispinis), and wood turtle (Macrochelys temminckii). Each of these species is experiencing steep population declines and ongoing threats to its existence. 2. To obtain federal safeguards and habitat protections, the Center and/or other conservation groups submitted to FWS petitions to list each of these nine species as “endangered” or “threatened” pursuant to the ESA. -

Genetic Diversity and Population Structure in the Barrens Topminnow

Conserv Genet DOI 10.1007/s10592-017-0984-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Genetic diversity and population structure in the Barrens Topminnow (Fundulus julisia): implications for conservation and management of a critically endangered species Carla Hurt1 · Bernard Kuhajda2 · Alexis Harman1 · Natalie Ellis1 · Mary Nalan1 Received: 5 January 2017 / Accepted: 22 May 2017 © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2017 Abstract The Barrens Topminnow (Fundulus julisia) with drainage boundaries. Results from AMOVA analysis has undergone a rapid and dramatic decline. In the 1980s, also suggest low levels of genetic connectivity between at least twenty localities with Barrens Topminnows were isolated populations within the same drainage. Here we known to exist in the Barrens Plateau region of middle Ten- propose two distinct evolutionary significant units (ESUs) nessee; currently only three areas with natural (not stocked) and two management units that reflect this population sub- populations remain. The long-term survival of the Barrens structure and warrant consideration in future management Topminnow will depend entirely on effective management efforts. and conservation efforts. Captive propagation and stocking of captive-reared juveniles to suitable habitats have suc- Keywords Conservation genetics · Microsatellites · cessfully established a handful of self-sustaining popula- Mitochondrial DNA · Endangered species · Fundulus tions. However, very little is known about the genetic com- julisia position of source and introduced populations including levels of genetic diversity and structuring of genetic vari- ation. Here we use both mitochondrial sequence data and Introduction genotypes from 14 microsatellite loci to examine patterns of genetic variation among ten sites, including all sites The Barrens Topminnow (Fundulus julisia) is one of with natural populations and a subset of sites with intro- the most critically endangered fish species in the east- duced (stocked) populations of this species. -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Food Habits of Imperiled Plains Topminnow and Diet Overlap With

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies Winter 3-1-2018 Food habits of imperiled Plains Topminnow and diet overlap with invasive Western Mosquitofish in the Central Great Plains Joseph Thiessen University of Nebraska at Kearney, [email protected] Keith D. Koupal Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, [email protected] Casey W. Schoenebeck University of Nebraska at Kearney, [email protected] Julie J. Shaffer University of Nebraska, Kearney Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas Part of the Population Biology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Thiessen, Joseph; Koupal, Keith D.; Schoenebeck, Casey W.; and Shaffer, Julie J., "Food habits of imperiled Plains Topminnow and diet overlap with invasive Western Mosquitofish in the Central Great Plains" (2018). Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies. 513. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas/513 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Academy of Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Food habits of imperiled Plains Topminnow and diet overlap with invasive Western Mosquitofish in the Central Great Plains Joseph D. Thiessen,1,4 Keith D. Koupal,2 Casey W. Schoenebeck,1,3 and Julie J. Shaffer 1 1 Department of Biology, University of Nebraska at Kearney, Kearney, NE 68849 2 Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Kearney Field Office, Kearney, NE 68847 3 Present address: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 23070 North Lakeshore Drive, Glenwood, MN 56334 4 Present address: Idaho Department of Fish and Game, 1414 E. -

Fisheries Full Issue PDF Volume 40, Issue 3

This article was downloaded by: [Department Of Fisheries] On: 19 July 2015, At: 23:50 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Fisheries Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ufsh20 Full Issue PDF Volume 40, Issue 3 Published online: 25 Mar 2015. Click for updates To cite this article: (2015) Full Issue PDF Volume 40, Issue 3, Fisheries, 40:3, 93-140, DOI: 10.1080/03632415.2015.1029803 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03632415.2015.1029803 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. -

Fishtraits: a Database on Ecological and Life-History Traits of Freshwater

FishTraits database Traits References Allen, D. M., W. S. Johnson, and V. Ogburn-Matthews. 1995. Trophic relationships and seasonal utilization of saltmarsh creeks by zooplanktivorous fishes. Environmental Biology of Fishes 42(1)37-50. [multiple species] Anderson, K. A., P. M. Rosenblum, and B. G. Whiteside. 1998. Controlled spawning of Longnose darters. The Progressive Fish-Culturist 60:137-145. [678] Barber, W. E., D. C. Williams, and W. L. Minckley. 1970. Biology of the Gila Spikedace, Meda fulgida, in Arizona. Copeia 1970(1):9-18. [485] Becker, G. C. 1983. Fishes of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI. Belk, M. C., J. B. Johnson, K. W. Wilson, M. E. Smith, and D. D. Houston. 2005. Variation in intrinsic individual growth rate among populations of leatherside chub (Snyderichthys copei Jordan & Gilbert): adaptation to temperature or length of growing season? Ecology of Freshwater Fish 14:177-184. [349] Bonner, T. H., J. M. Watson, and C. S. Williams. 2006. Threatened fishes of the world: Cyprinella proserpina Girard, 1857 (Cyprinidae). Environmental Biology of Fishes. In Press. [133] Bonnevier, K., K. Lindstrom, and C. St. Mary. 2003. Parental care and mate attraction in the Florida flagfish, Jordanella floridae. Behavorial Ecology and Sociobiology 53:358-363. [410] Bortone, S. A. 1989. Notropis melanostomus, a new speices of Cyprinid fish from the Blackwater-Yellow River drainage of northwest Florida. Copeia 1989(3):737-741. [575] Boschung, H.T., and R. L. Mayden. 2004. Fishes of Alabama. Smithsonian Books, Washington. [multiple species] 1 FishTraits database Breder, C. M., and D. E. Rosen. 1966. Modes of reproduction in fishes. -

Threatened and Endangered Species List

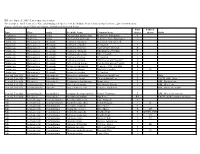

Effective April 15, 2009 - List is subject to revision For a complete list of Tennessee's Rare and Endangered Species, visit the Natural Areas website at http://tennessee.gov/environment/na/ Aquatic and Semi-aquatic Plants and Aquatic Animals with Protected Status State Federal Type Class Order Scientific Name Common Name Status Status Habit Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus gulolineatus Berry Cave Salamander T Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus bouchardi Big South Fork Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus cymatilis A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus deweesae Valley Flame Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus extraneus Chickamauga Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus obeyensis Obey Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus pristinus A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus williami "Brawley's Fork Crayfish" E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Fallicambarus hortoni Hatchie Burrowing Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes incomptus Tennessee Cave Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes shoupi Nashville Crayfish E LE Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes wrighti A Crayfish E Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris carthusiana Spinulose Shield Fern T Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris cristata Crested Shield-Fern T FACW, OBL, Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Trichomanes boschianum -

Social Learning and Its Effect on Conservation Efforts in the Barrens

SOCIAL LEARNING AND ITS EFFECT ON CONSERVATION EFFORTS IN THE BARRENS TOPMINNOW: AN EVALUATION OF CONDITIONING AND SOCIAL LEARNING AS A VIABLE LONGTERM SOLUTION TO EVOLUTIONARY TRAPS By Elijah Reyes Hope Klug David Aborn UC Foundation Associate Professor Associate Professor (Chair) (Committee Member) Bernard Kuhajda Sarah Farnsley TNACI Science Program Manager Lecturer (Committee Member) (Committee Member) SOCIAL LEARNING AND ITS EFFECT ON CONSERVATION EFFORTS IN THE BARRENS TOPMINNOW: AN EVALUATION OF CONDITIONING AND SOCIAL LEARNING AS A VIABLE LONGTERM SOLUTION TO EVOLUTIONARY TRAPS By Elijah Reyes A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of the Master of Science: Environmental Science The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee August 2017 ii ABSTRACT The invasive Western Mosquitofish (WMF), Gambusia affinis, has facilitated the extinction and endangerment of multiple freshwater fish species, including the Barrens Topminnow (BTM), Fundulus julisia. In my study, I investigated if BTMs are capable of socially learning conditioned predator recognition, and I hypothesized that BTMs are capable of social learning and that such learning might improve survival of BTMs. To explore the role of conditioning and subsequent learning in the conservation of BTMs, I conducted a series of experiments in which I 1) attempted to condition BTMs to exhibit antipredator behavior when faced with WMF, and 2) created a situation in which naive BTMs could potentially learn from conditioned individuals. I found no evidence of conditioning or of social learning, and there were no significant differences in behavior, body condition, or survival among my treatment groups. -

Guam Marine Biosecurity Action Plan

GuamMarine Biosecurity Action Plan September 2014 This Marine Biosecurity Action Plan was prepared by the University of Guam Center for Island Sustainability under award NA11NOS4820007 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Coral Reef Conservation Program, as administered by the Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management and the Bureau of Statistics and Plans, Guam Coastal Management Program. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Guam Marine Biosecurity Action Plan Author: Roxanna Miller First Released in Fall 2014 About this Document The Guam Marine Biosecurity Plan was created by the University of Guam’s Center for Island Sustainability under award NA11NOS4820007 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Coral Reef Conservation Program, as administered by the Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management and the Bureau of Statistics and Plans, Guam Coastal Management Program. Information and recommendations within this document came through the collaboration of a variety of both local and federal agencies, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program (CRCP), the University of Guam (UOG), the Guam Department of Agriculture’s Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources (DAWR), the United States Coast Guard (USCG), the Port Authority of Guam, the National Park Service -

Conditioning the Endangered Barrens Topminnow to Avoid

OVERCOMING EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY: CONDITIONING THE ENDANGERED BARRENS TOPMINNOW TO AVOID PREDATION BY THE INVASIVE WESTERN MOSQUITOFISH By Sarah Farnsley Hope Klug David Aborn Assistant Professor Associate Professor Biological and Environmental Sciences Biological and Environmental Sciences (Chair) (Committee Member) Bernard Kuhajda Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute (Committee Member) OVERCOMING EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY: CONDITIONING THE ENDANGERED BARRENS TOPMINNOW TO AVOID PREDATION BY THE INVASIVE WESTERN MOSQUITOFISH By Sarah Farnsley A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of the Master of Science: Environmental Science The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee May 2014 ii ABSTRACT Organisms use cues to assess their environment; however, environmental changes can create a mismatch between cues and the conditions with which they were historically associated. An evolutionary trap is when past selection pressures shaped cue-response systems that were once adaptive for an organism but no longer are. Invasive species are one cause of evolutionary traps, and the Barrens Topminnow (BTM), Fundulus julisia serves as an example of an imperiled species trapped by the introduction of an invasive predator: the Western Mosquitofish (WMF), Gambusia affinis. This study used conditioning to help the BTM escape its evolutionary trap, and data showed that conditioned fish responded significantly different to the presentation of -

Complex Interactions Between Native and Invasive Species: Investigating the Differential Displacement of Two Topminnows Native to Nebraska

Aquatic Invasions (2015) Volume 10, Issue 3: 339–346 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3391/ai.2015.10.3.09 Open Access © 2015 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2015 REABIC Research Article Complex interactions between native and invasive species: investigating the differential displacement of two topminnows native to Nebraska David A. Schumann1a*, W. Wyatt Hoback1b and Keith D. Koupal2 1University of Nebraska at Kearney, Department of Biology, 2401 11th Avenue, Kearney, Nebraska 68849, USA 2Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Kearney Field Office, 1617 1st Avenue, Kearney, Nebraska 68847, USA aCurrent address: Natural Resource Management, South Dakota State University, Box 2140B, SNP 138, Brookings, South Dakota 57007-1696, USA bCurrent address: Entomology and Plant Pathology, Oklahoma State University, 127 Noble Research Center, Stillwater, Oklahoma 74078-3033, USA *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] Received: 7 July 2014 / Accepted: 23 March 2015 / Published online: 7 April 2015 Handling editor: Kit Magellan Abstract The establishment of nonnative species and subsequent replacement of native species is among the greatest threats to freshwater biodiversity worldwide. However, little is known of the effects that invasive species have on individual species and specific mechanisms by which species displacement occurs. The expansion of western mosquitofish Gambusia affinis beyond its native range has commonly been thought to cause shifts in species assemblages throughout the United States. Although plains topminnow Fundulus sciadicus populations have declined as the range of western mosquitofish in Nebraska has expanded, long-term co-existence of mosquitofish with the closely related northern plains killifish Fundulus kansae has been observed within the same systems.