Maritime Briefing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Position Paper on ROC South China Sea Policy

Position Paper on ROC South China Sea Policy Republic of China (Taiwan) March 21, 2016 1. Preface The Nansha (Spratly) Islands, Shisha (Paracel) Islands, Chungsha (Macclesfield Bank) Islands, and Tungsha (Pratas) Islands (together known as the South China Sea Islands) were first discovered, named, and used by the ancient Chinese, and incorporated into national territory and administered by imperial Chinese governments. Whether from the perspective of history, geography, or international law, the South China Sea Islands and their surrounding waters are an inherent part of ROC territory and waters. The ROC enjoys all rights over them in accordance with international law. This is indisputable. Any claim to sovereignty over, or occupation of, these areas by other countries is illegal, irrespective of the reasons put forward or methods used, and the ROC government recognizes no such claim or occupation. With respect to international disputes regarding the South China Sea, the ROC has consistently maintained the principles of safeguarding sovereignty, shelving disputes, pursuing peace and reciprocity, and promoting joint development, and in accordance with the United Nations Charter and international law, called for consultations with other countries, participation in related dialogue and cooperative mechanisms, and peaceful 1 resolution of disputes, to jointly ensure regional peace. 2. Grounds for the ROC position History The early Chinese have been active in the South China Sea since ancient times. Historical texts and local gazetteers contain numerous references to the geographical position, geology, natural resources of the South China Sea waters and landforms, as well as the activities of the ancient Chinese in the region. The South China Sea Islands were discovered, named, used over the long term, and incorporated into national territory by the early Chinese, so even though most of the islands and reefs are uninhabited, they are not terra nullius. -

China's Historical Claim in the South China Sea

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-09-13 "Since Time Immemorial": China's Historical Claim in the South China Sea Chung, Chris Pak Cheong Chung, C. P. (2013). "Since Time Immemorial": China's Historical Claim in the South China Sea (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27791 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/955 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY “Since Time Immemorial”: China’s Historical Claim in the South China Sea by Chris P.C. Chung A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2013 © Chris Chung 2013 Abstract Four archipelagos in the South China Sea are territorially disputed: the Paracel, Spratly, and Pratas Islands, and Macclesfield Bank. The People’s Republic of China and Republic of China’s claims are embodied by a nine-dashed U-shaped boundary line originally drawn in an official Chinese map in 1948, which encompasses most of the South China Sea. Neither side has clarified what the line represents. Using ancient Chinese maps and texts, archival documents, relevant treaties, declarations, and laws, this thesis will conclude that it is best characterized as an islands attribution line, which centres the claim simply on the islands and features themselves. -

China's Claim of Sovereignty Over Spratly and Paracel Islands: a Historical and Legal Perspective Teh-Kuang Chang

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 23 | Issue 3 1991 China's Claim of Sovereignty over Spratly and Paracel Islands: A Historical and Legal Perspective Teh-Kuang Chang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Teh-Kuang Chang, China's Claim of Sovereignty over Spratly and Paracel Islands: A Historical and Legal Perspective, 23 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 399 (1991) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol23/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. China's Claim of Sovereignty Over Spratly and Paracel Islands: A Historical and Legal Perspective Teh-Kuang Chang* I. INTRODUCTION (Dn August 13, 1990, in Singapore, Premier Li Peng of the People's Re- public of China (the PRC) reaffirmed China's sovereignty over Xisha and Nansha Islands.1 On December. 29, 1990, in Taipei, Foreign Minis- ter Frederick Chien stated that the Nansha Islands are territory of the Republic of China.2 Both statements indicated that China's claim to sov- ereignty over the Paracel and Spratly Islands was contrary to the claims of other nations. Since China's claim of Spratly and Paracel Islands is challenged by its neighboring countries, the ownership of the islands in the South China Sea is an unsettled international dispute.3 An understanding of both * Professor of Political Science, Ball State University. -

China Versus Vietnam: an Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo

A CNA Occasional Paper China versus Vietnam: An Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo With a Foreword by CNA Senior Fellow Michael McDevitt August 2014 Unlimited distribution Distribution unlimited. for public release This document contains the best opinion of the authors at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Cover Photo: South China Sea Claims and Agreements. Source: U.S. Department of Defense’s Annual Report on China to Congress, 2012. Distribution Distribution unlimited. Specific authority contracting number: E13PC00009. Copyright © 2014 CNA This work was created in the performance of Contract Number 2013-9114. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in FAR 52-227.14. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. This project was made possible by a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation Approved by: August 2014 Ken E. Gause, Director International Affairs Group Center for Strategic Studies Copyright © 2014 CNA FOREWORD This legal analysis was commissioned as part of a project entitled, “U.S. policy options in the South China Sea.” The objective in asking experienced U.S international lawyers, such as Captain Raul “Pete” Pedrozo, USN, Judge Advocate Corps (ret.),1 the author of this analysis, is to provide U.S. -

The South China Sea Arbitration Case Filed by the Philippines Against China: Arguments Concerning Low Tide Elevations, Rocks, and Islands

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Xiamen University Institutional Repository 322 China Oceans Law Review (Vol. 2015 No. 1) The South China Sea Arbitration Case Filed by the Philippines against China: Arguments concerning Low Tide Elevations, Rocks, and Islands Yann-huei SONG* Abstract: On March 30, 2014, the Philippines submitted its Memorial to the Arbitral Tribunal, which presents the country’s case on the jurisdiction of the Tribunal and the merits of its claims. In the Memorial, the Philippines argues that Mischief Reef, Second Thomas Shoal, Subi Reef, Gaven Reef, McKennan Reef, Hughes Reef are low-tide elevations, and that Scarborough Shoal, Johnson Reef, Cuarteron Reef, and Fiery Cross Reef are “rocks”, therefore these land features cannot generate entitlement to a 200-nautical-mile EEZ or continental shelf. This paper discusses if the claims made by the Philippines are well founded in fact and law. It concludes that it would be difficult for the Tribunal to rule in favor of the Philippines’ claims. Key Words: Arbitration; South China Sea; China; The Philippines; Low tide elevation; Island; Rock; UNCLOS I. Introduction On January 22, 2013, the Republic of the Philippines (hereinafter “the Philippines”) initiated arbitral proceedings against the People’s Republic of China (hereinafter “China” or “PRC”) when it presented a Note Verbale1 to the Chinese * Yann-huie Song, Professor, Institute of Marine Affairs, College of Marine Sciences, Sun- yet Sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan and Research Fellow, Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan. E-mail: [email protected]. -

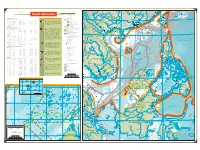

The Spratly Islands Administered by the Individual States of the Region and the Boundaries of Claims Versus the Exclusive Econom

The Spratly Islands administered by the individual states of the region and the boundaries of claims versus the exclusive economic zones and the boundaries of the continental shelf 0 25 50 75 100 km 0 25 50 75 100 NM 2009 VIETNAM 1974 Northeast Cay Southwest Cay Block Claim Vietnam Petroleum South Reef West York Island Thitu Island Subi Reef Irving Reef Flat Island Loaita Cay Nanshan Island Lankiam Cay Loaita Island a e Centre Cay Petley Reef S Itu Aba Island Sand Cay Gaven Reef a Namyit Island n i Discovery Great Reef 1979 Hughes Reef Mischief Reef h Sin Cowe Island C (Union Banks) Grierson Reef Collins Reef Higgens Reef Second Lansdowne Reef Thomas Shoal h Johnson South Reef t u Fiery Cross Reef First o Bombay Castle S Thomas Shoal 2009 2009 (London Reefs) PHILIPPINES Central Reef Pearson Reef Pigeon Reef 1979 West Reef Cuarteron Reef East Reef Alison Reef Ladd Reef Cornwallis South Reef Spratly Island Commodore Reef Prince of Wales Bank Barque Canada Reef Erica Reef Investigator Shoal Alexandra Bank Mariveles Reef Prince Consort Bank Amboyna Cay Grainger Bank Rifleman Bank Ardasier Reef Vanguard Bank Swallow Reef 1979 1979 The boundaries of the claims in the South China Sea have not been precisely delimited. This is their approximate location, presented for illustrative purposes only. for illustrative location, presented delimited. This is their approximate precisely not been Sea have the claims in the South China The boundaries of : MALAYSIA © / Reservation LEGEND Areas of land (islands, cays, reefs, rocks): Submerged areas and areas only partly above water: Boundaries of claims submitted by: Boundaries of the exclusive economic zones delimited pursuant to the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague issued in 2016 (case number 2013–19) and in line with the UNCLOS, i.e. -

Maritime Issues in the East and South China Seas

Maritime Issues in the East and South China Seas Summary of a Conference Held January 12–13, 2016 Volume Editors: Rafiq Dossani, Scott Warren Harold Contributing Authors: Michael S. Chase, Chun-i Chen, Tetsuo Kotani, Cheng-yi Lin, Chunhao Lou, Mira Rapp-Hooper, Yann-huei Song, Joanna Yu Taylor C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/CF358 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover image: Detailed look at Eastern China and Taiwan (Anton Balazh/Fotolia). Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Disputes over land features and maritime zones in the East China Sea and South China Sea have been growing in prominence over the past decade and could lead to serious conflict among the claimant countries. -

Defining EEZ Claims from Islands: a Potential South China Sea Change

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2014 Defining EEZ claims from islands: A potential South China Sea change Robert Beckman National University of Singapore, [email protected] Clive Schofield University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Beckman, Robert and Schofield, Clive, "Defining EEZ claims from islands: A potential South China Sea change" (2014). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 1409. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/1409 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Defining EEZ claims from islands: A potential South China Sea change Abstract In the face of seemingly intractable territorial and maritime disputes in the South China Sea, the article examines how the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOSC), sets out what maritime claims States can make in the South China Sea and how it establishes a framework that will enable States to either negotiate maritime boundary agreements or negotiate joint development arrangements (JDAs) in areas of overlapping maritime claims. It provides an avenue whereby the maritime claims of the claimants can be brought into line with international law, potentially allowing for meaningful discussions on cooperation and maritime joint development based on areas of overlapping maritime claims defined on the basis of the LOSC. -

Spratly Islands

R i 120 110 u T4-Y5 o Ganzhou Fuqing n h Chenzhou g Haitan S T2- J o Dao Daojiang g T3 S i a n Putian a i a n X g i Chi-lung- Chuxiong g n J 21 T6 D Kunming a i Xingyi Chang’an o Licheng Xiuyu Sha Lung shih O J a T n Guilin T O N pa Longyan T7 Keelung n Qinglanshan H Na N Lecheng T8 T1 - S A an A p Quanzhou 22 T'ao-yüan Taipei M an T22 I L Ji S H Zhongshu a * h South China Sea ng Hechi Lo-tung Yonaguni- I MIYAKO-RETTO S K Hsin-chu- m c Yuxi Shaoguan i jima S A T21 a I n shih Suao l ) Zhangzhou Xiamen c e T20 n r g e Liuzhou Babu s a n U T Taichung e a Quemoy p i Meizhou n i Y o J YAEYAMA-RETTO a h J t n J i Taiwan C L Yingcheng K China a a Sui'an ( o i 23 n g u H U h g n g Fuxing T'ai- a s e i n Strait Claimed Straight Baselines Kaiyuan H ia Hua-lien Y - Claims in the Paracel and Spratly Islands Bose J Mai-Liao chung-shih i Q J R i Maritime Lines u i g T9 Y h e n e o s ia o Dongshan CHINA u g B D s Tropic of Cancer J Hon n Qingyuan Tropic of Cancer Established maritime boundary ian J Chaozhou Makung n Declaration of the People’s Republic of China on the Baseline of the Territorial Sea, May 15, 1996 g i Pingnan Heyuan PESCADORES Taiwan a Xicheng an Wuzhou 21 25° 25.8' 00" N 119° 56.3' 00" E 31 21° 27.7' 00" N 112° 21.5' 00" E 41 18° 14.6' 00" N 109° 07.6' 00" E While Bandar Seri Begawan has not articulated claims to reefs in the South g Jieyang Chaozhou 24 T19 N BRUNEI Claim line Kaihua T10- Hsi-yü-p’ing Chia-i 22 24° 58.6' 00" N 119° 28.7' 00" E 32 19° 58.5' 00" N 111° 16.4' 00" E 42 18° 19.3' 00" N 108° 57.1' 00" E China Sea (SCS), since 1985 the Sultanate has claimed a continental shelf Xinjing Guiping Xu Shantou T11 Yü Luxu n Jiang T12 23 24° 09.7' 00" N 118° 14.2' 00" E 33 19° 53.0' 00" N 111° 12.8' 00" E 43 18° 30.2' 00" N 108° 41.3' 00" E X Puning T13 that extends beyond these features to a hypothetical median with Vietnam. -

The Continued Struggle in Western

American University International Law Review Volume 13 | Issue 3 Article 5 1998 In the Wake of Reno v. ACLU: The onC tinued Struggle in Western Constitutional Democracies with Internet Censorship and Freedom of Speech Online Kim L. Rappaport Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Rappaport, Kim L. "In the Wake of Reno v. ACLU: The onC tinued Struggle in Western Constitutional Democracies with Internet Censorship and Freedom of Speech Online." American University International Law Review 13, no. 3 (1998): 765-814. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TPJHUE 'IM OR GAP 'TREATY AS A MODEL FOR JOINT IDEVELOPMENT IN THE SPRATLY ISLANDS LIAN A. MITO Introduction .................................................... 728 I. The International Law Standard ............................. 730 A. Judicial Decisions ....................................... 730 B. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea .. 733 II. The Spratly Islands ......................................... 734 A. Background and History of the Dispute ................. 734 B. Claimant Countries -

Re-Framing the South China Sea: Geographical Reality and Historical Fact and Fiction

Re-framing the South China Sea: Geographical Reality and Historical Fact and Fiction Vivian Louis Forbes Universiti Brunei Darussalam Working Paper No.33 Institute of Asian Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam Gadong 2017 Editorial Board, Working Paper Series Professor Lian Kwen Fee, Institute of Asian Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam. Dr. Koh Sin Yee, Institute of Asian Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam. Author Dr Forbes is an Adjunct Research Professor at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, Haikou; a Distinguished Research Fellow and Guest Professor at the China Institute of Boundary and Ocean Studies, Wuhan University; a Senior Visiting Research Fellow with the Maritime Institute of Malaysia since 1993; and an Adjunct Professor at the University of Western Australia. Contact: [email protected] The Views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute of Asian Studies or the Universiti Brunei Darussalam. © Copyright is held by the author(s) of each working paper; no part of this publication may be republished, reprinted or reproduced in any form without permission of the paper’s author(s). 2 Re-framing the South China Sea: Geographical Reality and Historical Fact and Fiction Vivian Louis Forbes Abstract: The ‘labyrinth of detachable shoals’ in the South China Sea presented mariners during the late- 18th and early-19th centuries with a maritime area of considerable hazard that was best avoided. These same marine features now not only pose a problem for safe navigation within the South China Sea basin but have also challenged the minds of lawyers and politicians since the early- 1980s. -

Bill No. ___ an ACT IDENTIFYING the PHILIPPINE MARITIME

Bill No. ___ AN ACT IDENTIFYING THE PHILIPPINE MARITIME FEATURES OF THE WEST PHILIPPINE SEA, DEFINING THEIR RESPECTIVE APPLICABLE BASELINES, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES* EXPLANATORY NOTE In a few weeks, the country will mark the 5th year of the Philippines’ victory against China in the South China Sea (SCS) Arbitration. The Arbitral Award declared that China's Nine-Dash Line claim violates the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).1 It declared that the Philippines has an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and Continental Shelf (CS) in the areas of Panganiban (Mischief) Reef, Ayungin (Second Thomas) Shoal and Recto (Reed) Bank, and that Filipino fishermen have traditional fishing rights, in common with Chinese and Vietnamese fishermen, in the Territorial Sea (TS) of Bajo de Masinloc. Yet, the Philippines has remained unable to translate its victory into actual exercise of exclusive sovereign rights over fishing and resource exploitation in its recognized EEZ and CS and traditional fishing rights in the TS of Bajo de Masinloc. This proposed new baselines law seeks to break that impasse Firstly, it identifies by name and coordinates at least 100 features being claimed and occupied by the Philippines. This is an exercise of acts of sovereignty pertaining to each and every feature, consistent with the requirements of international law on the establishment and maintenance of territorial title. Secondly, it adopts normal baselines around each feature that qualifies as a high- tide elevation. This is to delineate the TS of each of said feature. Thirdly, it reiterates continuing Philippine sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdiction, as appropriate, over these features.