All Dogs Go to Heaven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artistic Subversions: Setting the Conditions of Display (Amsterdam, 2-4 Feb 17)

Artistic Subversions: Setting the Conditions of Display (Amsterdam, 2-4 Feb 17) Amsterdam, Feb 2–04, 2017 Deadline: Aug 30, 2016 Katja Kwastek Preceding the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam’s ‘Lose Yourself! – A Symposium on Labyrinthine Exhibitions as Curatorial Model’(03.-04.02.2017) this young researchers’ colloquium (02.02.2017) at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam will consider the strategies and methods by which artists take control over the space of installation. Without the artist’s permission Triple Candie, an exhibition space in New York, featured a retro- spective of Maurizio Cattelan. Entitled Maurizio Cattelan is Dead: Life & Work, 1960-2009 (2009), the show did not include a single work by the artist. Instead, it brought together a selection of pho- tocopied images from previous exhibitions with (vaguely recognizable) replicas of works by the artist. Cattelan, still very much alive, urged the Deste Foundation – established by Dakis Joannou, a prodigious collector of Cattelan’s work – to acquire the entirety of the show. In the foundation in Athens it was later installed in a room expressly selected by the artist. By repositioning the show in a new space of his own devise, Cattelan altered the conditions of its setting thereby incorporat- ing the complete exhibition into his oeuvre. This anecdote demonstrates a blurring of authorship between the artist and the curator, but it is also indicative of the significance of the setting of art, or its context, to its interpretation. This shift in emphasis to the conditions of display can be traced at least as far back as the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme (1938). -

TERENCE KOH Born 1980, China

TERENCE KOH Born 1980, China. Lives and works in NY. SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2003 Attack – The Kult 48 Klubhouse, K48 and Deitch Projects, NYC, NY. Today’s Man, Hiromi Yoshii, Tokyo, Japan. Game Over, Grimm/Rosenfeld, Munich, Germany. Mixer 03, Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago, Illinois. Now Playing, D’Amelio Terras, NYC, NY. Today’s Man, John Connely Presents, NYC, NY. DL: The Down Low in Contemporary Art, Longwood Art Gallery, Bronx, New York. Retreat, Peres Projects, Los Angeles, California. Hovering, Peres Projects, Los Angeles, California. 2004 Such things I do just to make myself more attractive to you, Peres Projects, Los Angeles, California. Biennial Exhibition, Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC, NY. Get Off! Exploring the Pleasure Principle, Museum of Sex, NYC, NY. Do a Book: Asian Artists Summer Project 2004, Plum Blossoms, NYC, NY. The Black Album, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, England. The Temple of Golden Piss, Extra City - Center for Contemporary Art, Antwerp, Belgium. Harlem Postcards Fall 2004, The Studio Museum in Harlem, NYC, NY. Phiiliip: Divided By Lightening, Deitch Projects, NYC, NY. 2006 Log Cabin, Artists Space, NYC, NY. No Ordinary Sanctity, Kunstraum Deutsche Bank, Salzburg, Austria. (curated by Shamim Momin) The Zine UnBound: Kults, Werewolves and Sarcastic Hippies, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, California. Blankness Is Not a Void, Standard, Oslo, Norway. (curated by Gardar Eide Einarsson) SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2011 Mary Boon Gallery, NYC, NY. 2009 Flowers for Baudor Baudelaire, Vito Schnabel Gallery, NYC, NY. ansonias, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris, France. Auta no Tama Raku, Domanus Gallery, Port-au-Prince, Haiti 2008 Captain Buddha, Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, Germany Love for Eternity, MUSAC, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León, Leon, Spain. -

Richard Prince Born in 1949, in the Panama Canal Zone, USA Biography Lives and Works in Upstate New York, USA

Richard Prince Born in 1949, in the Panama Canal Zone, USA Biography Lives and works in upstate New York, USA Solo Exhibitions 2019 'Richard Prince: Portrait', Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, Detroit, USA 2018 'Richard Prince - Works from the Astrup Fearnley Collection', Astrup Museet, Olso, Norway 'Untitled (Cowboy)', LACMA, Los Angeles, USA 2017 'Super Group Richard Prince', Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany 'Max Hetzler', Berlin, Germany 2016 The Douglas Blair Turnbaugh Collection (1977-1988)’, Edward Cella Art & Architecture, Los Angeles, USA Sadie Coles, London, UK 2015 'Original', Gagosian Gallery, New York, USA 'New Portraits', Blum & Poe, Tokyo, Japan 2014 'New Figures', Almine Rech Gallery, Paris, France 'It's a Free Concert', Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria 'Canal Zone', Gagosian Gallery, New York, USA 2013 Sadie Coles, London, UK 'Monochromatic Jokes', Nahmad Contemporary, New York, USA 'Protest Paintings', Skarstedt Gallery, London, UK 'Untitled (band', Le Case d'Arte, Milan, Italy 'New Work', Jürgen Becker, Hamburg, Germany 'Cowboys', Gagosian, Beverly Hills, USA 2012 ‘Prince / Picasso’, Museo Picasso Malaga, Spain 'White Paintings', Skarstedt Gallery, New York, USA 'Four Saturdays', gagosian Gallery, New York, USA '14 Paintings', 303 Gallery, New York, USA 64 rue de Turenne, 75003 Paris 18 avenue de Matignon, 75008 Paris [email protected] 2011 - ‘The Fug’, Almine Rech Gallery, Brussels, Belgium Abdijstraat 20 rue de l’Abbaye Brussel 1050 Bruxelles ‘Covering Pollock’, The Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, USA [email protected] -

Press Release (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y 14 June 2016 I called some paintings perspectives but I'm not interested in perspective; I called some butterflies but I don't think they are butterflies; I call my sculptures masks but they are not masks. —Mark Grotjahn Gagosian Gallery is pleased to present “Pink Cosco,” an exhibition of new, large-scale painted bronze sculptures by Mark Grotjahn. Grotjahn's work is inseparable from its present moment, yet willing to make explicit art-historical reference. He borrows from Op art, Abstract Expressionism, Pop art, and Renaissance perspective, but achieves effects that reach forward and backward simultaneously. To occupy this precarious past-future visual position requires intense concentration, calculation, and control. As he painted his Butterfly paintings, Grotjahn sought an escape from precision: he began making masks out of the cardboard boxes lying around his studio—the discarded shells of art materials, gifts, and other packaging. He painted the boxes and attached toilet paper roll tubes that stuck out between cut-out eyes. The Masks, although originally started as a casual practice, quickly asserted themselves as a new armature for painting—an armature that would straddle time just as much as the two-dimensional geometric works. (Continue to page 2) 2 0 G R O S V E N O R H I L L L O N D O N W 1 K 3 Q D T . 0 2 0 . 7 4 9 5 . 1 5 0 0 F . 0 2 0 . 7 4 9 5 . -

Gillian Wearing Biography

GILLIAN WEARING BIOGRAPHY Born in Birmingham, United Kingdom, 1963 Lives and works in London, United Kingdom. Education: Goldsmiths' College, University of London, B.A. (Hons.) Fine Art, 1990 Chelsea School of Art, B.TECH Art & Design, 1987 Solo Exhibitions: 2014 Gillian Wearing, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA, December 11, 2014 – January 24, 2015 Gillian Wearing, Maureen Paley, London, UK, October 13 – November 16, 2014 Rose Video 05 | Gillian Wearing, The Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA, November 11, 2014 – March 8, 2015 We Are Here, The New Art Gallery Walsall, Walsall, UK, 18 July – 12 October 2014 2013 Gillian Wearing, Museum Brandhorst, Munich, Germany, March 21 – July 7, 2013. PEOPLE: Selected Parkett Artists’ Editions from 1984-2013, Parkett Space, Zurich, Switzerland, February 9 – March 11, 2013. 2012 Gillian Wearing, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, United Kingdom, March 28 – June 17, 2012; travels to K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf, Germany, September 8 – January 6, 2013; Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, Germany, March – July 2013. 2011 Gillian Wearing: People, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, NY, May 5 – June 24, 2011 2009 Gillian Wearing: Confessions/ Portraits, Videos, Musée Rodin, Paris, France, April 10 – August 23, 2009 2008 Gillian Wearing: Pin-Ups and Family History, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA, July 12 – August 23, 2008 2007 Gillian Wearing: Family Monument, special project curated by Fabio Cavallucci and Cristina Natalicchio, Galleria Civica de Arte Contemporanea di Trento, -

Sean Landers Cv 2021 0223

SEAN LANDERS Born 1962, Palmer, MA Lives and works in New York, NY EDUCATION 1986 MFA, Yale University School of Art, New Haven, CT 1984 BFA, Philadelphia College of Art, Philadelphia, PA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, 2020 Vision, April 26–ongoing (online presentation) Greengrassi, London, UK, Northeaster, June 16–July 31 Consortium Museum, Dijon, France, March 13– October 18, curated by Eric Troncy 2019 Ben Brown Fine Arts, Hong Kong, China, November 12–January 9, 2020 Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium, November 9–December 20 (catalogue) Petzel Bookstore, New York, NY, Curated by . Featuring Sean Landers, November 7– December 14 Freehouse, London, UK, Sean Landers: Studio Films 90/95, curated by Daren Flook, January 13–February 24 2018 Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, March 1–April 21 (catalogue) 2016 Capitain Petzel, Berlin, Germany, Sean Landers: Small Brass Raffle Drum, September 16– October 29 2015 Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan, December 5–January 16, 2016 Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium, October 29–December 19 (catalogue) China Art Objects, Los Angeles, CA, February 21–April 11 2014 Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, Sean Landers: North American Mammals, November 13– December 20 (catalogue) 2012 Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium, November 8–December 21(catalogue) Sorry We’re Closed, Brussels, Belgium, Longmore, November 8–December 21 greengrassi, London, UK, April 26–June 16 1 2011 Friedrich Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, Sean Landers: Around the World Alone, May 6–June 25 Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, NY, Sean Landers: A Midnight Modern Conversation, April 21–June 18 (catalogue) 2010 Contemporary Art Museum St. -

The Next Gen Art Collectors 2021

COLLECTORS 1 THE NEXT COLLECTORS REPORT 2021 3 LARRY’S LIST is pleased to present The Next Gen that have not yet been acknowledged or made visible For us, size wasn’t a main consideration. Indeed, not a blue-chip artist will most likely generate more “likes” FOREWORDArt Collectors Report. Here, we continue our mission on a global scale. We want to share their stories and everyone listed has a large collection; charmingly, the than an unknown artist in an equally brilliant interior of monitoring global happenings, developments and thoughts. Next Gen often have collections in the making. The setting. But we still try to balance it and set aside any trends in the art world—particularly in the contemporary We also consider LARRY’S LIST as a guide and tool process is a development that happens over years care about the algorithm. art collector field—by looking extensively at the next for practitioners. We share and name collectors, those and so a mid-20-year-old collector may not yet be at generation of young art collectors on the scene. Over people who are buying art and contributing to the the same stage in their collection as someone in their Final words the past few months, we have investigated and profiled art scene. The Next Gen Art Collectors Report is a late 30s. I would like to express my gratitude to all the collectors these collectors, answering the questions central to this resource for artists, galleries, dealers, a general art- The end result of our efforts is this report listing over we exchanged with in the preparation of this report topic: Who are these collectors founding the next art interested audience and, of course, peer collectors. -

A Fiery Splash in the Rockaways and Twists on Film at the Whitney

ART & DESIGN A Fiery Splash in the Rockaways and Twists on Film at the Whitney By ROBIN POGREBIN MAY 26, 2016 Japan Society Show When the Turner Prize-winning artist Simon Starling was preparing the piece he would exhibit at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art five years ago, he learned about masked Japanese Noh theater, which inspired W. B. Yeats’s 1916 play, “At the Hawk’s Well.” Now Mr. Starling is building on that project with “At Twilight,” his first institutional show in New York and a rare solo exhibition at Japan Society that features a non-Japanese artist. It is also the first exhibition by Yukie Kamiya, Japan Society’s new gallery director, who used to be chief curator at the Hiroshima museum. The show is organized with the Common Guild of Glasgow, which will present Mr. Starling’s version of the Yeats play in July. Mr. Starling said that he was intrigued by the idea of masked theater, “where nobody is who they appear to be.” Pogrebin, Robin, “A Fiery Splash in the Rockaways and Twists on Film at the Whitney”, The New York Times (online), May 26, 2016 The Grand Tour: Simon Starling 19 Mar 2016 - 26 Jun 2016 Nottingham Contemporary presents Turner Prize-winner Simon Starling’s largest exhibition in the UK to date. The exhibition will include a new artwork developed in collaboration with Not- tingham Trent University, of which Starling is an alumnus and a number of Starling’s major proj- ects, most of which have not been presented in Britain before. -

DONALD JUDD Born 1928 in Excelsior Springs, Missouri

This document was updated January 6, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. DONALD JUDD Born 1928 in Excelsior Springs, Missouri. Died 1994 in New York City. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1957 Don Judd, Panoras Gallery, New York, NY, June 24 – July 6, 1957. 1963–1964 Don Judd, Green Gallery, New York, NY, December 17, 1963 – January 11, 1964. 1966 Don Judd, Leo Castelli Gallery, 4 East 77th Street, New York, NY, February 5 – March 2, 1966. Donald Judd Visiting Artist, Hopkins Center Art Galleries, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, July 16 – August 9, 1966. 1968 Don Judd, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, February 26 – March 24, 1968 [catalogue]. Don Judd, Irving Blum Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, May 7 – June 1, 1968. 1969 Don Judd, Leo Castelli Gallery, 4 East 77th Street, New York, NY, January 4 – 25, 1969. Don Judd: Structures, Galerie Ileana Sonnabend, Paris, France, May 6 – 29, 1969. New Works, Galerie Bischofberger, Zürich, Switzerland, May – June 1969. Don Judd, Galerie Rudolf Zwirner, Cologne, Germany, June 4 – 30, 1969. Donald Judd, Irving Blum Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, September 16 – November 1, 1969. 1970 Don Judd, Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, January 16 – March 1, 1970; traveled to Folkwang Museum, Essen, Germany, April 11 – May 10, 1970; Kunstverein Hannover, Germany, June 20 – August 2, 1970; and Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, United Kingdom, September 29 – November 1, 1970 [catalogue]. Don Judd, The Helman Gallery, St. Louis, MO, April 3 – 29, 1970. Don Judd, Leo Castelli Gallery, 4 East 77th Street, and 108th Street Warehouse, New York, NY, April 11 – May 9, 1970. -

CHRISTOPHER WOOL Born 1955, Chicago, IL Lives and Works in New York, NY and Marfa, TX

CHRISTOPHER WOOL Born 1955, Chicago, IL Lives and works in New York, NY and Marfa, TX SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, London, England 2019 Christopher Wool, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL.* Maybe Maybe Not : Christopher Wool and the Hill Collection, Hill Art Foundation, New York, NY. 2018 Christopher Wool : A New Sculpture, Luhring Augustine Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY. Christopher Wool : Highlights from the Hill Art Collection, H Queens, Hong Kong. 2017 Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany.* Text Without Message, Philbrook Downtown, Tulsa, OK. 2016 Christopher Wool, Daros Collection at Fondation Beyeler, Hurden, Switzerland. 2015 Christopher Wool, Luhring Augustine, New York, NY; Luhring Augustine Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY. Christopher Wool: Selected Paintings, McCabe Fine Art, Stockholm, Sweden. Inbox: Christopher Wool, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. 2013-2014 Christopher Wool, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY; The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL.* 2013 Christopher Wool: Works on Paper, 1989-1990, Art & Public, Geneva, Switzerland. 2012 Christopher Wool, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France.* 2011 Christopher Wool, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany. * A catalogue was published with this exhibition. 2010 Christopher Wool, Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy.* Christopher Wool: Sound on Sound, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL.* 2009 Christopher Wool: Editions, Artelier Contemporary, Graz, Austria. Christopher Wool, Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium. 2008-2009 Christopher Wool: Porto-Köln, Fundação de Serralves: Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Porto, Portugal; Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany.* 2008 Christopher Wool, Luhring Augustine, New York, NY. 2007 Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany.* Christopher Wool, Eleni Koroneou Gallery, Athens, Greece. -

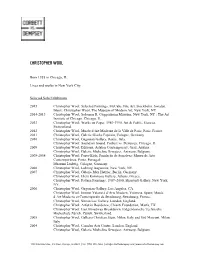

Wool CV1.Pdf

CHRISTOPHER WOOL Born 1955 in Chicago, IL. Lives and works in New York City. Selected Solo Exhibitions 2015 Christopher Wool: Selected Paintings, McCabe Fine Art, Stockholm, Sweden. Inbox: Christopher Wool, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. 2014-2013 Christopher Wool, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY ; The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL. 2013 Christopher Wool: Works on Paper, 1989-1990, Art & Public, Geneva, Switzerland. 2012 Christopher Wool, Musée d‘Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France. 2011 Christopher Wool, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany. 2010 Christopher Wool, Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy. Christopher Wool: Sound on Sound, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL. 2009 Christopher Wool: Editions, Artelier Contemporary, Graz, Austria. Christopher Wool, Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium. 2009-2008 Christopher Wool: Porto-Köln, Fundação de Serralves: Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Porto, Portugal; Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany. 2008 Christopher Wool, Luhring Augustine, New York, NY. 2007 Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany. Christopher Wool, Eleni Koroneou Gallery, Athens, Greece. Christopher Wool: Pattern Paintings, 1987–2000, Skarstedt Gallery, New York, NY. 2006 Christopher Wool, Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. Christopher Wool, Institut Valencià d‘Arte Modern, Valencia, Spain; Musée d‘Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France. Christopher Wool, Simon Lee Gallery, London, England. Christopher Wool: Artist in Residence, Chianti Foundation, Marfa, TX. Christopher Wool: East Broadway Breakdown, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland. 2005 Christopher Wool, Galleria Christian Stein, Milan, Italy and Gió Marconi, Milan, Italy. 2004 Christopher Wool, Camden Arts Centre, London, England. Christopher Wool, Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium. 1120 N Ashland Ave., 3rd Floor, Chicago, IL 60622 | Tel. -

Éric Hussenot

Éric Hussenot 5 bis rue des Haudriettes 75003 Paris 01 48 87 60 81 [email protected] www.galeriehussenot.com assume vivid astro focus assume vivid astro focus is comprised of Eli Sudbrack and Christophe Hamaide- Pierson. Eli Sudbrack was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and lives and works between São Paulo and New York. Christophe Hamaide-Pierson was born in Paris and lives and works in Paris. solo exhibitions 2015 Peres Projects, Berlin, Germany (forthcoming) Contagious, site-specific permanent installation for CAC, Cincinnati, USA 2014 ángeles veloces arcanos fugaces, Faena Arts Center, Buenos Aires, Argentina adderall valium ativan focalin (cantilevering me), The Suzanne Geiss Company, New York, NY, USA Mural installation, MASP (Museu de Arte de São Paulo) 2013 alisabel viril apagão fenomenal , Casa Triangulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil The Armory Show, The Suzanne Geiss Company, Focus Section, curated by Eric Shiner 2012 Featured artist of 2012 Gala, The Museum de Arte Moderna, São Paulo 2011 Cyclops Trannies, The Suzanne Geiss Company, New York, New York Silent Disco, One night performance and installation for the opening of Turner Contemporary, Margate, UK all very amazing fingers, Mural Installation, City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, Philadelphia Illegitimo, Mural Installation, LIGHTBOX, Miami Cyclops Trannies, Galeria Triângulo, SP Arte, São Paulo, Brazil 2010 archeologist verifies acid flashbacks, The Wynwood Walls, Miami, Florida Wallpaper and Neon Installation, Core Club, New York, New York Ilegítimo, MOCA Cleveland, Cleveland,