Commission for Global Road Safety CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Download Just Choose the Ones I Can Afford and Take to Have Some Grasp of Whereabouts in the and Own – Any Big Finish Production

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES REUNITING THE REBELS IN WARSHIP WHAT’S IN STORE IN GALLIFREY V ISSUE 48 • FEBRUARY 2013 ANIMATING THE REIGN OF TERROR PLUS CHASE MASTERSON DISCUSSES VIENNA VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 1 VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 2 SNEAK PREVIEWS EDITORIAL AND WHISPERS ello! You were expecting Nick Briggs weren’t you? I’m H afraid he’s in a booth at the minute, hissing and growling. This is not a condition brought on by overwork… Oh no, he’s back in the armour of an Ice Warrior, acting away for the recording of Doctor Who – The Lost Stories: Lords of the Red Planet. The six-part story, which was originally devised by Brian Hayles for TV back in 1968, will be out on audio in November – and form another part of Big Finish’s massive fiftieth anniversary celebrations. And what celebrations they will be! As I write, we’re well into recording our multi-Doctor special The Light at the End, and it’s been a blast. Admittedly it’s been strange to DOCTOR WHO: THE LIGHT AT THE END see the Doctors in the studio at the same time. We’re so used to them being in separately, and suddenly they’re ‘We want something special from Big Finish for here together! But there’s been a real sense of this being the fiftieth anniversary,’ they said. a massive party – the green room chatter has been really We like a challenge, so we went to town jolly and vibrant. It’s so nice to see that all these actors love with this one – eight Doctors (yes, incarnations Doctor Who just as much as we do. -

“My” Hero Or Epic Fail? Torchwood As Transnational Telefantasy

“My” Hero or Epic Fail? Torchwood as Transnational Telefantasy Melissa Beattie1 Recibido: 2016-09-19 Aprobado por pares: 2017-02-17 Enviado a pares: 2016-09-19 Aceptado: 2017-03-23 DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo Beattie, M. (2017). “My” hero or epic fail? Torchwood as transnational telefantasy. Palabra Clave, 20(3), 722-762. DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Abstract Telefantasy series Torchwood (2006–2011, multiple production partners) was industrially and paratextually positioned as being Welsh, despite its frequent status as an international co-production. When, for series 4 (sub- titled Miracle Day, much as the miniseries produced as series 3 was subti- tled Children of Earth), the production (and diegesis) moved primarily to the United States as a co-production between BBC Worldwide and Amer- ican premium cable broadcaster Starz, fan response was negative from the announcement, with the series being termed Americanised in popular and academic discourse. This study, drawn from my doctoral research, which interrogates all of these assumptions via textual, industrial/contextual and audience analysis focusing upon ideological, aesthetic and interpretations of national identity representation, focuses upon the interactions between fan cultural capital and national cultural capital and how those interactions impact others of the myriad of reasons why the (re)glocalisation failed. It finds that, in part due to the competing public service and commercial ide- ologies of the BBC, Torchwood was a glocalised text from the beginning, de- spite its positioning as Welsh, which then became glocalised again in series 4. -

Stonyhurst Association Newsletter 306 July 2013

am dg Ston y hurSt GES RU 1762 . B .L 3 I 9 E 5 G 1 E S 1 R 7 7 E 3 M . O 4 T S 9 . 7 S 1 T O ST association news N YHUR STONYHURST newsletter 306 ASSOjulyC 2013IATION 1 GES RU 1762 . B .L 3 I 9 E G StonyhurSt association 5 1 E S 1 R 7 7 E 3 M . O 4 francis xavier scholarships T S 9 newsletter . 7 S 1 T O ST N YHUR The St Francis Xavier Award is a scholarship being awarded for entry to newSlet ter 306 a mdg july 2013 Stonyhurst. These awards are available at 11+ and 13+ for up to 10 students who, in the opinion of the selection panel, are most likely to benefitS from,T andO NYHURST contribute to, life as full boarders in a Catholic boarding school. Assessments for contentS the awards comprise written examinations and one or more interviews. diary of events 4 Applicants for the award are expected to be bright pupils who will fully participate in all aspects of boarding school life here at Stonyhurst. St Francis In memoriam 4 Xavier Award holders will automatically benefit from a fee remissionA of 20%S andS OCIATION thereafter may also apply for a means-tested bursary, worth up to a further 50% Congratulations 5 off the full boarding fees. 50 years ago 6 The award is intended to foster the virtues of belief, ambition and hard work which Francis Xavier exemplified in pushing out the boundaries of the Christian reunions 7 faith. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Torchwood Doctor Who: Wicked Sisters Big Finish

ISSUE: 140 • OCTOBER 2020 WWW.BIGFINISH.COM THE TENTH DOCTOR AND RIVER SONG TOGETHER AGAIN, BUT IN WHAT ORDER? PLUS: BLAKE’S 7 | TORCHWOOD DOCTOR WHO: WICKED SISTERS BIG FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULLCAST AUDIO WE LOVE STORIES! DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND OR ABOUT BIG FINISH DOWNLOAD Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, WWW.BIGFINISH.COM Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, The @BIGFINISH Avengers, The Prisoner, The THEBIGFINISH Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain Scarlet, Space: BIGFINISHPROD 1999 and Survivors, as well BIG-FINISH as classics such as HG Wells, BIGFINISHPROD Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the SUBSCRIPTIONS Opera and Dorian Gray. If you subscribe to our Doctor We also produce original BIG FINISH APP Who The Monthly Adventures creations such as Graceless, The majority of Big Finish range, you get free audiobooks, Charlotte Pollard and The releases can be accessed on- PDFs of scripts, extra behind- Adventures of Bernice the-go via the Big Finish App, the-scenes material, a bonus Summereld, plus the Big available for both Apple and release, downloadable audio Finish Originals range featuring Android devices. readings of new short stories seven great new series: ATA and discounts. Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence Secure online ordering and Investigate, Blind Terror, details of all our products can Transference and The Human be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF Frontier. BIG FINISH WELL, THIS is rather exciting, isn’t it, more fantastic THE DIARY OF adventures with the Tenth Doctor and River Song! For many years script editor Matt Fitton and I have both dreamed of RIVER SONG hearing stories like this. -

See a Full List of the National Youth

Past Productions National Youth Theatre '50s 1956: Henry V - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Toynbee Hall 1957: Henry IV Pt II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Toynbee Hall 1957: Henry IV Pt II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Worthington Hall, Manchester 1958: Troilus & Cressida - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Moray House Theatre, Edinburgh 1958: Troilus & Cressida - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith '60s 1960: Hamlet - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Tour of Holland. Theatre des Nations. Paris 1961: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Apollo Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue 1961: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Ellen Terry Theatre. Tenterden. Devon 1961: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @Apollo Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue 1961: Henry IV Pt II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Apollo Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue 1961: Julius Caesar - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ British entry at Berlin festival 1962: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Italian Tour: Rome, Florence, Genoa, Turin, Perugia 1962: Richard II - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Tour of Holland and Belgium 1962: Henry V - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Sadlers Wells 1962: Julius Caesar - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Sadlers Wells1962: 1962: Hamlet - William Shakespeare, Dir: Michael Croft @ Tour for Centre 42. Nottingham, Leicester, Birmingham, Bristol, Hayes -

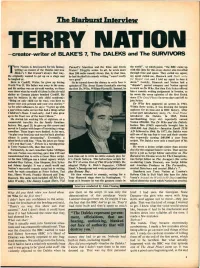

T H E S L a R B U R S T I N T E R V I E W T E R R Y N a T I

The Slarburst Interview TERRY NATION -creator-writer of BLAKE'S 7, The DALEKS and The SURVIVORS erry Nation is best-known for his fantasy Parnell's Startime and the Elsie and Doris the world". At which point, "the BBC came up writing: as creator of the Daleks and now Waters' Floggits series. In all, he wrote more with this idea for this crazy doctor who travelled TBlake's 7. But it wasn't always that way. than 200 radio comedy shows. But, by that time, through time and space. They called my agent, He originally wanted to get up on a stage and he had decided his comedy writing "wasn't really my agent called me, Hancock said Don't write be laughed at. very good". for flippiri' kids and I told my agent to turn it Born in Cardiff, Wales, he grew up during So he turned down the chance to write four tv down." Luckily, Hancock and Nation had a World War II. His father was away in the army episodes of The Army Game (ironically starring "dispute", parted company and Nation agreed and his mother was an air-raid warden, so there the first Dr. Who, William Hartnell). Instead, he to work on Dr Who. But then Eric Sykes offered were times when he would sit alone in the air-raid him a comedy writing assignment in Sweden, so shelter as German planes bombed Cardiff. He he wrote the seven episodes of the first Dalek says he believes in the only child syndrome: story (The Dead Planet) in seven days and left to "Being an only child (as he was), you have to join Sykes. -

Created and Written by Academy Award-Winner Julian Fellowes Directed by Michael Engler

Created and Written by Academy Award-Winner Julian Fellowes Directed by Michael Engler Press Pack CONTENTS Cast ..................................................................................................................................................6 Guest Cast .......................................................................................................................................7 Filmmakers & Creatives ....................................................................................................................7 Downton Abbey Synopsis ................................................................................................................8 The Genesis of Downton Abbey .......................................................................................................9 The Making of the Downton Abbey Film by Julian Fellowes..........................................................14 Filmmakers & Creative Interviews: Gareth Neame ................................................................................................................................16 Liz Trubridge ...................................................................................................................................21 Michael Engler ................................................................................................................................25 Donal Woods ..................................................................................................................................28 Anna Robbins -

Consultation on the Devolution of Broadcasting Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee January 2020

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru / National Assembly for Wales Pwyllgor Diwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chyfathrebu / Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee Datganoli Darlledu / Devolution of Broadcasting CWLC DoB23 Ymateb gan BBC / Response from BBC Consultation on the Devolution of Broadcasting Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee January 2020 Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru / National Assembly for Wales Pwyllgor Diwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chyfathrebu / Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee Datganoli Darlledu / Devolution of Broadcasting CWLC DoB23 Ymateb gan BBC / Response from BBC 1. Introduction The BBC has been a cornerstone of Welsh life since the first broadcast in Wales nearly a century ago and BBC Wales is the country’s principal public service broadcaster. The Royal Charter is the constitutional basis for the BBC. It sets out the BBC’s Aims, Mission and Public Purposes. The Charter also outlines the Corporation’s governance and regulatory arrangements, including the role and composition of the BBC Board. The current Charter began on 1 January 2017 and ends on 31 December 2027. The BBC will not offer any view on the advisability - or otherwise - of devolving broadcasting since to do so would risk undermining the BBC’s commitment to impartiality on what is, clearly, a matter of public significance and ongoing political debate. However, to allow an informed debate to be conducted by the Committee, we believe it is valuable to set out some facts and figures about the BBC in Wales and to provide consistent data and a shared resource of information for interested parties. The information within this document relates to 2018/19, the period of the most recent BBC Annual Report & Accounts. -

B7update.Pdf

UPDATE First published in the UK in 2012 by Telos Publishing Ltd 17 Pendre Avenue, Prestatyn, Denbighshire LL19 9SH www.telos.co.uk Telos Publishing Ltd values feedback. Please e-mail us with any comments you may have about this book to: [email protected] Blake’s 7: The Merchandise Guide Update © 2012 Mark B Oliver The moral right of the author has been asserted. Original internal design, typesetting and layout by Arnold T Blumberg. Layout of this update by David VanRiper. All photographs, artwork and illustrations kindly donated for use in this publication are copyright their respective owners and are printed here with permission. The photograph of the Space Command badge (CBA-006) appears courtesy of, and is copyright, Rob Emery. The illustration in Appendix A which advertised Blake’s 7 – A Marvel Monthly, appears courtesy of Ian Kennedy. The artwork in Appendix C appears courtesy of, and is copyright, Gauda Prime Designs. Excerpts of copyrighted sources are included for review purposes only, without any intention of infringement. INDEX Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………….……..1 Abbreviations…….….…………………………………………………………………….1 Rarity Guide……………………………………………………………………………….1 Consistency…….….……………………………………….…….……………………….2 Criteria……………………………………………………….………………………….…2 Introduction….……….……………………………………………………………………2 Audio…………………………………………………………………………………….…4 Audio, Books….………………………………………………………….………….……4 Audio, Themes………………….………………………………………….…………..…5 Books…………………………………………………………………….……..………… 6 Books, Activity……………………………………………………………………….……6 Books, -

PRIME TIME:Soldiers Discuss Making Bbc Documentary

PRIME TIME: Soldiers discuss MakIng BBc documenTaRy DefenceFocus Royal Navy | Army | Royal Air Force | Ministry of Defence | issue #252 JUNE/11 FIVE yEaRS In HElMand combatbarbie NANAVIGATORVIGATOR stars and stripes: soldier presents Fa CUp - p23 Regulars Lifestyle p5 In memorIam p24 boys’ toys Tributes to the fallen GSM WO1 Bill Mott voices action figure p18 verbatIm p28 health matters MOD spokesman General Lorimer Living with diabetes p14 podIum p31 Grand designs Legacy of bin Laden’s death p22 Win a stay at London’s Grand Hotel Exclusives p8 FIve years In helmand The story of UK operations p12 apaches Apaches remain strong in Helmand p16 war on wIdescreen Combat through a soldier’s eyes p24 p26 changinG places p31 Civilian Jenna Clare’s Afghan deployment JUNE 2011 | ISSUE 252 | 3 EDITOR’SNOTE DefenceFocus DANNY CHAPMAN For everyone in defence Is it me or do things seem a bit quieter We are in fact all the busier tracking Published by the Ministry of Defence than normal? Of course announcements down more everyday, but nonetheless Level 1 Zone C seem to be like buses, no big ones for a important and interesting stories about MOD, Main Building while, then three or four come along at what’s going on. Whitehall London SW1A 2HB once, then it all goes quiet again. These have included online stories General enquiries: 020 721 8 1320 In this week that we are going to about heroic acts on operations being print we’ve announced the Armed Forces recognised, units returning from EDITOR: Danny Chapman Tel: 020 7218 3949 Covenant is to be enshrined in law, the Helmand, ships departing for far off seas email: [email protected] end of operations in Iraq and the approval and the daily actions being taken by the ASSISTANT EDITOR: Ian Carr of the early design phase for a successor RAF and Navy against Gaddafi’s regime in Tel: 020 7218 2825 submarine to Trident.