Antipsychotics Systematic Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The In¯Uence of Medication on Erectile Function

International Journal of Impotence Research (1997) 9, 17±26 ß 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0955-9930/97 $12.00 The in¯uence of medication on erectile function W Meinhardt1, RF Kropman2, P Vermeij3, AAB Lycklama aÁ Nijeholt4 and J Zwartendijk4 1Department of Urology, Netherlands Cancer Institute/Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital, Plesmanlaan 121, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 2Department of Urology, Leyenburg Hospital, Leyweg 275, 2545 CH The Hague, The Netherlands; 3Pharmacy; and 4Department of Urology, Leiden University Hospital, P.O. Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands Keywords: impotence; side-effect; antipsychotic; antihypertensive; physiology; erectile function Introduction stopped their antihypertensive treatment over a ®ve year period, because of side-effects on sexual function.5 In the drug registration procedures sexual Several physiological mechanisms are involved in function is not a major issue. This means that erectile function. A negative in¯uence of prescrip- knowledge of the problem is mainly dependent on tion-drugs on these mechanisms will not always case reports and the lists from side effect registries.6±8 come to the attention of the clinician, whereas a Another way of looking at the problem is drug causing priapism will rarely escape the atten- combining available data on mechanisms of action tion. of drugs with the knowledge of the physiological When erectile function is in¯uenced in a negative mechanisms involved in erectile function. The way compensation may occur. For example, age- advantage of this approach is that remedies may related penile sensory disorders may be compen- evolve from it. sated for by extra stimulation.1 Diminished in¯ux of In this paper we will discuss the subject in the blood will lead to a slower onset of the erection, but following order: may be accepted. -

The Effects of Antipsychotic Treatment on Metabolic Function: a Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis

The effects of antipsychotic treatment on metabolic function: a systematic review and network meta-analysis Toby Pillinger, Robert McCutcheon, Luke Vano, Katherine Beck, Guy Hindley, Atheeshaan Arumuham, Yuya Mizuno, Sridhar Natesan, Orestis Efthimiou, Andrea Cipriani, Oliver Howes ****PROTOCOL**** Review questions 1. What is the magnitude of metabolic dysregulation (defined as alterations in fasting glucose, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglyceride levels) and alterations in body weight and body mass index associated with short-term (‘acute’) antipsychotic treatment in individuals with schizophrenia? 2. Does baseline physiology (e.g. body weight) and demographics (e.g. age) of patients predict magnitude of antipsychotic-associated metabolic dysregulation? 3. Are alterations in metabolic parameters over time associated with alterations in degree of psychopathology? 1 Searches We plan to search EMBASE, PsycINFO, and MEDLINE from inception using the following terms: 1 (Acepromazine or Acetophenazine or Amisulpride or Aripiprazole or Asenapine or Benperidol or Blonanserin or Bromperidol or Butaperazine or Carpipramine or Chlorproethazine or Chlorpromazine or Chlorprothixene or Clocapramine or Clopenthixol or Clopentixol or Clothiapine or Clotiapine or Clozapine or Cyamemazine or Cyamepromazine or Dixyrazine or Droperidol or Fluanisone or Flupehenazine or Flupenthixol or Flupentixol or Fluphenazine or Fluspirilen or Fluspirilene or Haloperidol or Iloperidone -

Antipsychotics and the Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death

ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION Antipsychotics and the Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death Sabine M. J. M. Straus, MD; Gyse`le S. Bleumink, MD; Jeanne P. Dieleman, PhD; Johan van der Lei, MD, PhD; Geert W. ‘t Jong, PhD; J. Herre Kingma, MD, PhD; Miriam C. J. M. Sturkenboom, PhD; Bruno H. C. Stricker, PhD Background: Antipsychotics have been associated with Results: The study population comprised 554 cases of prolongation of the corrected QT interval and sudden car- sudden cardiac death. Current use of antipsychotics was diac death. Only a few epidemiological studies have in- associated with a 3-fold increase in risk of sudden car- vestigated this association. We performed a case- diac death. The risk of sudden cardiac death was high- control study to investigate the association between use est among those using butyrophenone antipsychotics, of antipsychotics and sudden cardiac death in a well- those with a defined daily dose equivalent of more than defined community-dwelling population. 0.5 and short-term (Յ90 days) users. The association with current antipsychotic use was higher for witnessed cases Methods: We performed a population-based case-control (n=334) than for unwitnessed cases. study in the Integrated Primary Care Information (IPCI) project, a longitudinal observational database with com- Conclusions: Current use of antipsychotics in a gen- plete medical records from 150 general practitioners. All eral population is associated with an increased risk of sud- instances of death between January 1, 1995, and April 1, den cardiac death, even at a low dose and for indica- 2001, were reviewed. Sudden cardiac death was classified tions other than schizophrenia. -

Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Second Generation

Forensic Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Exactive Plus High-Resolution Accurate Mass Spectrometer and ExactFinder Software Kristine Van Natta, Marta Kozak, Xiang He Forensic Toxicology use Only Drugs analyzed Compound Compound Compound Atazanavir Efavirenz Pyrilamine Chlorpropamide Haloperidol Tolbutamide 1-(3-Chlorophenyl)piperazine Des(2-hydroxyethyl)opipramol Pentazocine Atenolol EMDP Quinidine Chlorprothixene Hydrocodone Tramadol 10-hydroxycarbazepine Desalkylflurazepam Perimetazine Atropine Ephedrine Quinine Cilazapril Hydromorphone Trazodone 5-(p-Methylphenyl)-5-phenylhydantoin Desipramine Phenacetin Benperidol Escitalopram Quinupramine Cinchonine Hydroquinine Triazolam 6-Acetylcodeine Desmethylcitalopram Phenazone Benzoylecgonine Esmolol Ranitidine Cinnarizine Hydroxychloroquine Trifluoperazine Bepridil Estazolam Reserpine 6-Monoacetylmorphine Desmethylcitalopram Phencyclidine Cisapride HydroxyItraconazole Trifluperidol Betaxolol Ethyl Loflazepate Risperidone 7(2,3dihydroxypropyl)Theophylline Desmethylclozapine Phenylbutazone Clenbuterol Hydroxyzine Triflupromazine Bezafibrate Ethylamphetamine Ritonavir 7-Aminoclonazepam Desmethyldoxepin Pholcodine Clobazam Ibogaine Trihexyphenidyl Biperiden Etifoxine Ropivacaine 7-Aminoflunitrazepam Desmethylmirtazapine Pimozide Clofibrate Imatinib Trimeprazine Bisoprolol Etodolac Rufinamide 9-hydroxy-risperidone Desmethylnefopam Pindolol Clomethiazole Imipramine Trimetazidine Bromazepam Felbamate Secobarbital Clomipramine Indalpine Trimethoprim Acepromazine Desmethyltramadol Pipamperone -

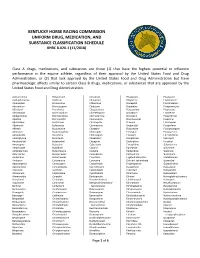

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

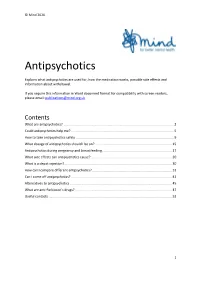

Antipsychotics-2020.Pdf

© Mind 2020 Antipsychotics Explains what antipsychotics are used for, how the medication works, possible side effects and information about withdrawal. If you require this information in Word document format for compatibility with screen readers, please email: [email protected] Contents What are antipsychotics? ...................................................................................................................... 2 Could antipsychotics help me? .............................................................................................................. 5 How to take antipsychotics safely ......................................................................................................... 9 What dosage of antipsychotics should I be on? .................................................................................. 15 Antipsychotics during pregnancy and breastfeeding ........................................................................... 17 What side effects can antipsychotics cause? ....................................................................................... 20 What is a depot injection? ................................................................................................................... 30 How can I compare different antipsychotics? ..................................................................................... 31 Can I come off antipsychotics? ............................................................................................................ 41 Alternatives to antipsychotics -

In Vivo Labeling of the Dopamine D2 Receptor with N-' €˜C-Methyl-Benperidol

In Vivo Labeling of the Dopamine D2 Receptor with N-' ‘C-Methyl-Benperidol Makiko Suehiro, Robert F. Dannals, Ursula Scheffel, Mango Stathis, Alan A. Wilson, Hayden T. Ravert, Victor L. Villemagne, Patricia M. Sanchez-Roa, and Henry N. Wagner, Jr. Division ofNuclear Medicine and Radiation Health Sciences, The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland been reported to be close to 50% ofthe amount bound A new dopamine D2 receptor radiotracer, N-11C-methyl to the dopamine receptor in striatum (11). With the benperidol(11C-NMB), was prepared and its in vivo biologic methylated derivative, N-methyl-spiperone, @—‘2O%of behavior in mice and a baboon was studied. Carbon-i 1- the binding of this compound in the striatum and 90% NMB was determined to bind to specific sites character in the frontal cortex was characterized as binding to the ized as dopamine D2 receptors. The binding was satura serotonin S2 receptor (15). As a result, in PET brain ble, reversible, and stereospecific. Kineticstudies in the images with spiperone or its derivatives, the tissues with dopamine D2 receptor-rich stnatum showed that 11C-NMB low densities of dopamine receptors but an abundance was retained five times longer than in receptor-devoid of serotonin S2 receptors, such as frontal cortex and regions, resulting in a high maximum stnatal-to-cerebellar ratio of 11:1 at 60 mm after injection.From frontal cortex cortex, are visualized as well as dopamine receptor-rich and cortex, on the other hand, the tracer washed out as tissues. rapidlyas it did fromcerebellum,resultingin tissue-to This poor selectivity is a disadvantage ofthese ligands cerebellar ratios dose to one in these regions at any time as dopamine D2 receptor radiotracers. -

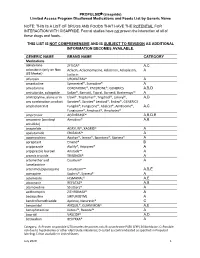

PROPULSID® (Cisapride) Limited Access Program

PROPULSID (cisapride) Limited Access Program Disallowed Medications and Foods List by Generic Name NOTE: THIS IS A LIST OF DRUGS AND FOODS THAT HAVE THE POTENTIAL FOR INTERACTION WITH CISAPRIDE. Formal studies have not proven the interaction of all of these drugs and foods. THIS LIST IS NOT COMPREHENSIVE AND IS SUBJECT TO REVISION AS ADDITIONAL INFORMATION BECOMES AVAILABLE. GENERIC NAME BRAND NAME CATEGORY Medications abiraterone ZYTIGA® A,C aclarubicin (only on Non Aclacin, Aclacinomycine, Aclacinon, Aclaplastin, A US Market) Jaclacin alfuzosin UROXATRAL® A amantadine Symmetrel®, Symadine® A amiodarone CORDARONE®, PACERONE®, GENERICS A,B,D amisulpride, sultopride Solian®, Barnotil, Topral, Barnetil, Barhemsys™ A amitriptyline, alone or in Elavil®, Tryptomer®, Tryptizol®, Laroxyl®, A,D any combination product Saroten®, Sarotex® Lentizol®, Endep®, GENERICS amphotericin B Fungilin®, Fungizone®, Abelcet®, AmBisome®, A,C Fungisome®, Amphocil®, Amphotec® amprenavir AGENERASE® A,B,D,E amsacrine (acridinyl Amsidine® A,B anisidide) anagrelide AGRYLIN®, XAGRID® A apalutamide ERLEADA™ A apomorphine Apokyn®, Ixense®, Spontane®, Uprima® A aprepitant Emend® B aripiprazole Abilify®, Aripiprex® A aripiprazole lauroxil Aristada™ A arsenic trioxide TRISENOX® A artemether and Coartem® A lumefantrine artenimol/piperaquine Eurartesim™ A,B,E asenapine Saphris®, Sycrest® A astemizole HISMANAL® A,E atazanavir REYATAZ® A,B atomoxetine Strattera® A azithromycin ZITHROMAX® A bedaquiline SIRTURO(TM) A bendroflumethiazide Aprinox, Naturetin® C benperidol ANQUIL®, -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/00398.69 A1 Wermeling Et Al

US 200600398.69A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/00398.69 A1 Wermeling et al. (43) Pub. Date: Feb. 23, 2006 (54) INTRANASAL DELIVERY OF Publication Classification ANTIPSYCHOTC DRUGS (51) Int. Cl. A6IK 9/14 (2006.01) A61 K 3/445 (2006.01) A6IL 9/04 (2006.01) (76) Inventors: Daniel Wermeling, Lexington, KY (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................. 424/46; 514/317 (US); Jodi Miller, Acworth, GA (US) (57) ABSTRACT An intranasal drug product is provided including an antip Correspondence Address: Sychotic drug, Such as haloperidol, in Sprayable Solution in MAYER, BROWN, ROWE & MAW LLP an intranasal metered dose Sprayer. Also provided is a P.O. BOX2828 method of administering an antipsychotic drug, Such as CHICAGO, IL 60690-2828 (US) haloperidol, to a patient, including the Step of delivering an effective amount of the antipsychotic drug to a patient intranasally using an intranasal metered dose Sprayer. A (21) Appl. No.: 10/920,153 method of treating a psychotic episode also is provided, the method including the Step of delivering an antipsychotic drug, Such as haloperidol, intranasally in an amount effective (22) Filed: Aug. 17, 2004 to control the psychotic episode. Patent Application Publication Feb. 23, 2006 US 2006/00398.69 A1 30 525 2 20 -- Treatment A (M) S 15 - Treatment B (IM) 10 -- Treatment C (IN) i 2 O 1 2 3 4 5 6 Time Post-dose (hours) F.G. 1 US 2006/0039869 A1 Feb. 23, 2006 INTRANASAL DELIVERY OF ANTIPSYCHOTC therefore the dosage form of choice in acute situations. In DRUGS addition, the oral Solution cannot be "cheeked' by patients. -

Electronic Search Strategies

Appendix 1: electronic search strategies The following search strategy will be applied in PubMed: ("Antipsychotic Agents"[Mesh] OR acepromazine OR acetophenazine OR amisulpride OR aripiprazole OR asenapine OR benperidol OR bromperidol OR butaperazine OR Chlorpromazine OR chlorproethazine OR chlorprothixene OR clopenthixol OR clotiapine OR clozapine OR cyamemazine OR dixyrazine OR droperidol OR fluanisone OR flupentixol OR fluphenazine OR fluspirilene OR haloperidol OR iloperidone OR levomepromazine OR levosulpiride OR loxapine OR lurasidone OR melperone OR mesoridazine OR molindone OR moperone OR mosapramine OR olanzapine OR oxypertine OR paliperidone OR penfluridol OR perazine OR periciazine OR perphenazine OR pimozide OR pipamperone OR pipotiazine OR prochlorperazine OR promazine OR prothipendyl OR quetiapine OR remoxipride OR risperidone OR sertindole OR sulpiride OR sultopride OR tiapride OR thiopropazate OR thioproperazine OR thioridazine OR tiotixene OR trifluoperazine OR trifluperidol OR triflupromazine OR veralipride OR ziprasidone OR zotepine OR zuclopenthixol ) AND ("Randomized Controlled Trial"[ptyp] OR "Controlled Clinical Trial"[ptyp] OR "Multicenter Study"[ptyp] OR "randomized"[tiab] OR "randomised"[tiab] OR "placebo"[tiab] OR "randomly"[tiab] OR "trial"[tiab] OR controlled[ti] OR randomized controlled trials[mh] OR random allocation[mh] OR double-blind method[mh] OR single-blind method[mh] OR "Clinical Trial"[Ptyp] OR "Clinical Trials as Topic"[Mesh]) AND (((Schizo*[tiab] OR Psychosis[tiab] OR psychoses[tiab] OR psychotic[tiab] OR disturbed[tiab] OR paranoid[tiab] OR paranoia[tiab]) AND ((Child*[ti] OR Paediatric[ti] OR Pediatric[ti] OR Juvenile[ti] OR Youth[ti] OR Young[ti] OR Adolesc*[ti] OR Teenage*[ti] OR early*[ti] OR kids[ti] OR infant*[ti] OR toddler*[ti] OR boys[ti] OR girls[ti] OR "Child"[Mesh]) OR "Infant"[Mesh])) OR ("Schizophrenia, Childhood"[Mesh])). -

Hypothermia Due to Antipsychotic Medication Zonnenberg, Cherryl; Bueno-De-Mesquita, Jolien M.; Ramlal, Dharmindredew; Blom, Jan Dirk

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Hypothermia due to Antipsychotic Medication Zonnenberg, Cherryl; Bueno-de-Mesquita, Jolien M.; Ramlal, Dharmindredew; Blom, Jan Dirk Published in: Frontiers in Psychiatry DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00165 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Zonnenberg, C., Bueno-de-Mesquita, J. M., Ramlal, D., & Blom, J. D. (2017). Hypothermia due to Antipsychotic Medication: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, [165]. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00165 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 12-11-2019 SYSTEMATIC REVIEW published: 07 September 2017 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00165 Hypothermia due to Antipsychotic Medication: A Systematic Review Cherryl Zonnenberg1, Jolien M. -

SARS-Cov-2 Orf1b Gene Sequence in the NTNG1 Gene on Human Chromosome 1 STEVEN LEHRER 1 and PETER H

in vivo 34 : 1629-1632 (2020) doi:10.21873/invivo.11953 SARS-CoV-2 orf1b Gene Sequence in the NTNG1 Gene on Human Chromosome 1 STEVEN LEHRER 1 and PETER H. RHEINSTEIN 2 1Department of Radiation Oncology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, U.S.A.; 2Severn Health Solutions, Severna Park, MD, U.S.A. Abstract. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV- (SARS-CoV-2) is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus. 2) is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus (1). The rapid It is contagious in humans and is the cause of the coronavirus spread of the infection suggests that the virus could have disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. In the current analysis, adapted in the past to human hosts. If so, some of its gene we searched for SARS-CoV-2 sequences within the human sequences might be found in the human genome. To investigate genome. To compare the SARS-CoV-2 genome to the human this possibility, we utilized the UCSC Genome Browser, an on- genome, we used the blast-like alignment tool (BLAT) of the line genome browser at the University of California, Santa University of California, Santa Cruz Genome Browser. BLAT Cruz (UCSC) (https://genome.ucsc.edu) (2). can align a user sequence of 25 bases or more to the genome. To compare the SARS-CoV-2 genome to the human BLAT search results revealed a 117-base pair SARS-CoV-2 genome, we used the blast-like alignment tool (BLAT) of the sequence in the human genome with 94.6% identity.