Transnational Organized Crime and the Impact on the Private Sector: the Hidden Battalions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High-Profile Cyberattack Investigations: London's Met Police

High-Profile Cyberattack Investigations: London’s Met Police Share Takeaways Raymond Black | Metropolitan Police About the Speaker • 1990 to 1996 - Uniformed officer working in various locations across South London • 1996 to 2000 - Detective working in various locations across South London • 2000 to 2006 - Territorial Support Group (Riot police) – (2002 to 2003 - Worked in private sector management in Durban South Africa for transport and construction company) • 2006 to 2014 - Operation Trident (proactive firearms and gangs unit) – (2012 to 2013 - Employed by European Union investigating government corruption in Guatemala) • 2014 to Present – Cyber crime investigator Specialist Cyber Crime Unit • Other deployments working in various roles in Jamaica, The Netherlands, Poland and the United States 2 #ISMGSummits ROCU Map 1. North East (NERSOU) 2. Yorkshire & Humber (ODYSSEY) 3. North West (TITAN) 4. Southern Wales (TARIAN) 5. West Midlands 6. East Midlands (EMSOU) 7. Eastern (ERSOU) 8. South West (ZEPHYR) 9. London 10. South East (SEROCU) NATIONAL COORDINATION 3 #ISMGSummits Remit of MPCCU To deal with the most serious offences of: • Cyber-crime facilitated by the use and control of malicious software (malware). • Cyber-crime facilitated by the use of online phishing techniques. • Computer and network intrusions (dependant upon motives and objectives). • Denial of service attacks and website defacement (dependant upon motives and objectives). • The online trade in financial, personal and other data obtained through cyber-crime. • The intentional and dishonest online provision of services, tools etc. to facilitate cyber-crime. 4 #ISMGSummits Threshold of MPCCU • Where life is put at risk • Targeting or impacting on public safety, emergency services or other public systems and services. -

An Evolving Threat the Deep Web

8 An Evolving Threat The Deep Web Learning Objectives distribute 1. Explain the differences between the deep web and darknets.or 2. Understand how the darknets are accessed. 3. Discuss the hidden wiki and how it is useful to criminals. 4. Understand the anonymity offered by the deep web. 5. Discuss the legal issues associated withpost, use of the deep web and the darknets. The action aimed to stop the sale, distribution and promotion of illegal and harmful items, including weapons and drugs, which were being sold on online ‘dark’ marketplaces. Operation Onymous, coordinated by Europol’s Europeancopy, Cybercrime Centre (EC3), the FBI, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) and Eurojust, resulted in 17 arrests of vendors andnot administrators running these online marketplaces and more than 410 hidden services being taken down. In addition, bitcoins worth approximately USD 1 million, EUR 180,000 Do in cash, drugs, gold and silver were seized. —Europol, 20141 143 Copyright ©2018 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. 144 Cyberspace, Cybersecurity, and Cybercrime THINK ABOUT IT 8.1 Surface Web and Deep Web Google, Facebook, and any website you can What Would You Do? find via traditional search engines (Internet Explorer, Chrome, Firefox, etc.) are all located 1. The deep web offers users an anonym- on the surface web. It is likely that when you ity that the surface web cannot provide. use the Internet for research and/or social What would you do if you knew that purposes you are using the surface web. -

HOW to RUN a ROGUE GOVERNMENT TWITTER ACCOUNT with an ANONYMOUS EMAIL ADDRESS and a BURNER PHONE Micah Lee February 20 2017, 9:53 A.M

HOW TO RUN A ROGUE GOVERNMENT TWITTER ACCOUNT WITH AN ANONYMOUS EMAIL ADDRESS AND A BURNER PHONE Micah Lee February 20 2017, 9:53 a.m. Illustration: Doug Chayka for The Intercept LEIA EM PORTUGUÊS ⟶ One of the first things Donald Trump did when he took office was tem- porarily gag several federal agencies, forbidding them from tweeting. In response, self-described government workers created a wave of rogue Twitter accounts that share real facts (not to be confused with “alterna- tive facts,” otherwise known as “lies”) about climate change and sci- ence. As a rule, the people running these accounts chose to remain anonymous, fearing retaliation — but, depending on how they created and use their accounts, they are not necessarily anonymous to Twitter itself, or to anyone Twitter shares data with. Anonymous speech is firmly protected by the First Amendment and the Supreme Court, and its history in the U.S. dates to the Federalist Papers, written in 1787 and 1788 under the pseudonym Publius by three of the founding fathers. But the technical ability for people to remain anonymous on today’s in- ternet, where every scrap of data is meticulously tracked, is an entirely different issue. The FBI, a domestic intelligence agency that claims the power to spy on anyone based on suspicions that don’t come close to probable cause, has a long, dark history of violating the rights of Ameri- cans. And now it reports directly to President Trump, who is a petty, re- venge-obsessed authoritarian with utter disrespect for the courts and the rule of law. -

MEMO. Nº. 52/2017 – SCOM

00100.096648/2017-00 MEMO. nº. 52/2017 – SCOM Brasília, 21 de junho de 2017 A Sua Excelência a Senhora SENADORA REGINA SOUSA Assunto: Ideia Legislativa nº. 76.334 Senhora Presidente, Nos termos do parágrafo único do art. 6º da Resolução do Senado Federal nº. 19 de 2015, encaminho a Vossa Excelência a Ideia Legislativa nº. 76.334, sob o título de “Criminalização Da Apologia Ao Comunismo”, que alcançou, no período de 09/06/2017 a 20/06/2017, apoiamento superior a 20.000 manifestações individuais, conforme a ficha informativa em anexo. Respeitosamente, Dirceu Vieira Machado Filho Diretor da Secretaria de Comissões Senado Federal – Praça dos Três Poderes – CEP 70.165-900 – Brasília DF ARQUIVO ASSINADO DIGITALMENTE. CÓDIGO DE VERIFICAÇÃO: CE7C06D2001B6231. CONSULTE EM http://www.senado.gov.br/sigadweb/v.aspx. 00100.096648/2017-00 ANEXO AO MEMORANDO Nº. 52/2017 – SCOM - FICHA INFORMATIVA E RELAÇÃO DE APOIADORES - Senado Federal – Praça dos Três Poderes – CEP 70.165-900 – Brasília DF ARQUIVO ASSINADO DIGITALMENTE. CÓDIGO DE VERIFICAÇÃO: CE7C06D2001B6231. CONSULTE EM http://www.senado.gov.br/sigadweb/v.aspx. 00100.096648/2017-00 Ideia Legislativa nº. 76.334 TÍTULO Criminalização Da Apologia Ao Comunismo DESCRIÇÃO Assim como a Lei já prevê o "Crime de Divulgação do Nazismo", a apologia ao COMUNISMO e seus símbolos tem que ser proibidos no Brasil, como já acontece cada vez mais em diversos países, pois essa ideologia genocida causou males muito piores à Humanidade, massacrando mais de 100 milhões de inocentes! (sic) MAIS DETALHES O art. 20 da Lei 7.716/89 estabeleceu o "Crime de Divulgação do Nazismo": "§1º - Fabricar, comercializar, distribuir ou veicular, símbolos, emblemas, ornamentos, distintivos ou propaganda que utilizem a cruz suástica ou gamada, para fins de divulgação do nazismo. -

“Guía Metodológica De Uso Seguro De Internet Para Personas Y Empresas Utilizando La Red Tor”

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DEL ECUADOR FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA ESCUELA DE SISTEMAS DISERTACIÓN DE GRADO PREVIA A LA OBTENCIÓN DEL TÍTULO DE INGENIERO EN SISTEMAS Y COMPUTACIÓN “GUÍA METODOLÓGICA DE USO SEGURO DE INTERNET PARA PERSONAS Y EMPRESAS UTILIZANDO LA RED TOR” NOMBRES: Javier Andrés Vicente Alarcón Verónica Cristina Guillén Guillén DIRECTOR: Msc. Luis Alberto Pazmiño Proaño QUITO, 2015 “GUÍA METODOLÓGICA DE USO SEGURO DE INTERNET PARA PERSONAS Y EMPRESAS UTILIZANDO LA RED TOR” TABLA DE CONTENIDO RESUMEN .......................................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCCIÓN ................................................................................................................ 6 0. ANTECEDENTES ......................................................................................................... 8 0.1. Internet .............................................................................................................. 8 0.1.1. Definición .................................................................................................... 8 0.1.2. Historia........................................................................................................ 9 0.1.3. Evolución .................................................................................................. 12 0.2. Ciberataque ...................................................................................................... 13 0.2.1. Definición ................................................................................................. -

Date 1.1.2015 1.1.2015 1.1.2015 1.1.2015 1.1.2015 1.1

Date 1.1.2015 1.1.2015 1.1.2015 1.1.2015 1.1.2015 1.1.2015 1.1.2015 2.1.2015 2.1.2015 2.1.2015 2.1.2015 3.1.2015 3.1.2015 4.1.2015 4.1.2015 4.1.2015 5.1.2015 5.1.2015 5.1.2015 6.1.2015 6.1.2015 6.1.2015 7.1.2015 7.1.2015 7.1.2015 7.1.2015 7.1.2015 8.1.2015 9.1.2015 10.1.2015 11.1.2015 11.1.2015 11.1.2015 11.1.2015 11.1.2015 11.1.2015 11.1.2015 12.1.2015 12.1.2015 12.1.2015 12.1.2015 12.1.2015 12.1.2015 14.1.2015 14.1.2015 14.1.2015 14.1.2015 14.1.2015 15.1.2015 15.1.2015 15.1.2015 16.1.2015 16.1.2015 16.1.2015 16.1.2015 16.1.2015 16.1.2015 17.1.2015 17.1.2015 17.1.2015 19.1.2015 19.1.2015 20.1.2015 20.1.2015 20.1.2015 21.1.2015 21.1.2015 22.1.2015 23.1.2015 23.1.2015 24.1.2015 24.1.2015 24.1.2015 25.1.2015 25.1.2015 26.1.2015 27.1.2015 27.1.2015 27.1.2015 27.1.2015 27.1.2015 28.1.2015 28.1.2015 29.1.2015 29.1.2015 29.1.2015 29.1.2015 30.1.2015 30.1.2015 30.1.2015 31.1.2015 1.2.2015 1.2.2015 1.2.2015 1.2.2015 1.2.2015 2.2.2015 2.2.2015 2.2.2015 2.2.2015 2.2.2015 4.2.2015 5.2.2015 5.2.2015 5.2.2015 6.2.2015 6.2.2015 7.2.2015 8.2.2015 8.2.2015 9.2.2015 9.2.2015 10.2.2015 10.2.2015 10.2.2015 10.2.2015 10.2.2015 10.2.2015 10.2.2015 10.2.2015 12.2.2015 12.2.2015 12.2.2015 12.2.2015 12.2.2015 13.2.2015 13.2.2015 14.2.2015 14.2.2015 14.2.2015 14.2.2015 14.2.2015 14.2.2015 14.2.2015 15.2.2015 16.2.2015 16.2.2015 16.2.2015 17.2.2015 17.2.2015 17.2.2015 17.2.2015 17.2.2015 17.2.2015 18.2.2015 18.2.2015 18.2.2015 18.2.2015 19.2.2015 21.2.2015 21.2.2015 22.2.2015 23.2.2015 23.2.2015 23.2.2015 23.2.2015 23.2.2015 23.2.2015 24.2.2015 24.2.2015 24.2.2015 -

2000-Deep-Web-Dark-Web-Links-2016 On: March 26, 2016 In: Deep Web 5 Comments

Tools4hackers -This You website may uses cookies stop to improve me, your experience. but you We'll assume can't you're ok stop with this, butus you all. can opt-out if you wish. Accept Read More 2000-deep-web-dark-web-links-2016 on: March 26, 2016 In: Deep web 5 Comments 2000 deep web links The Dark Web, Deepj Web or Darknet is a term that refers specifically to a collection of websites that are publicly visible, but hide the IP addresses of the servers that run them. Thus they can be visited by any web user, but it is very difficult to work out who is behind the sites. And you cannot find these sites using search engines. So that’s why we have made this awesome list of links! NEW LIST IS OUT CLICK HERE A warning before you go any further! Once you get into the Dark Web, you *will* be able to access those sites to which the tabloids refer. This means that you could be a click away from sites selling drugs and guns, and – frankly – even worse things. this article is intended as a guide to what is the Dark Web – not an endorsement or encouragement for you to start behaving in illegal or immoral behaviour. 1. Xillia (was legit back in the day on markets) http://cjgxp5lockl6aoyg.onion 2. http://cjgxp5lockl6aoyg.onion/worldwide-cardable-sites-by-alex 3. http://cjgxp5lockl6aoyg.onion/selling-paypal-accounts-with-balance-upto-5000dollars 4. http://cjgxp5lockl6aoyg.onion/cloned-credit-cards-free-shipping 5. 6. ——————————————————————————————- 7. -

Un Paseo Por La Deep Web

UN PASEO POR LA DEEP WEB TFM en empresa: INCIBE Máster Interuniversitario de Seguridad de las Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones Jorge ÁLVAREZ RODRÍGUEZ Jorge CHINEA LÓPEZ Víctor GARCIA FONT 30 de diciembre de 2018 Esta obra está sujeta a una licencia de Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 3.0 España de Creative Commons A Patricia, a Nira. FICHA DEL TRABAJO FINAL Título del trabajo: Un paseo por la Deep Web Nombre del autor: Jorge ÁLVAREZ RODRÍGUEZ Nombre del consultor/a: Jorge CHINEA LÓPEZ Nombre del PRA: Víctor GARCIA FONT Fecha de entrega: 12/2018 Máster Interuniversitario en Seguridad de Titulación: las Tecnologías de la Información y de las Comunicaciones Área del Trabajo Final: TFM en empresa: INCIBE Idioma del trabajo: Castellano Palabras clave: Deep Web Resumen del Trabajo: “Un paseo por la Deep Web” presenta de forma clara y ordenada los principales aspectos que rodean a la conocida como Internet profunda. Partiendo de la definición de la Deep Web, se observan las diferencias entre Surface Web, Dark Web y Darknet. Sentadas las bases de lo que es cada ecosistema se hace un repaso por las Darknets más conocidas, así como otras que empiezan a aflorar. Las más populares, Tor, Freenet e I2P, son analizadas en profundidad, determinando sus principales características y su modo de trabajo y comparando las tres, esgrimiendo sus ventajas y sus inconvenientes. Una vez que ya se ha accedido a la Dark Web, el siguiente paso es descubrir que hay en estas redes, sus contenidos y los servicios que ofrecen y aprovechar para desterrar la idea de que la Dark Web solo está llena de ciberdelincuentes, sino que hay muchas más posibilidades y forma de uso totalmente licitas, eso sí, con la característica común de guardar el anonimato y privacidad del usuario. -

02 Anonimato Con Tor (PDF)

Comunicaciones Seguras Anonimato con Tor Rafael Bonifaz: [email protected] 1/18 ¿Por qué anonimato en Internet? ● Toda actividad en Internet deja huella ● Dirección IP ● Ubicación geográfica ● Búsquedas asociadas a una persona ● Hacer denuncias ● Filtrar información a Wikileaks ● Mucho más 2/18 Opciones de anonimato ● Tor es la opción más reconocida y funciona solo con TCP ● I2P cumple objetivos similares a Tor, pero técnicamente diferente ● Soporta TCP y UDP ● FreeNet es red de distribución de información descentralizada, resistente a la censura ● VPNs 3/18 ¿Cómo Funciona Tor? 4/18 Sin Tor y sin HTTPS https://www.eff.org/pages/tor-and-https 5/18 Con HTTPS y sin Tor https://www.eff.org/pages/tor-and-https 6/18 Con Tor y sin HTTPS https://www.eff.org/pages/tor-and-https 7/18 Con Tor y sin HTTPS https://www.eff.org/pages/tor-and-https 8/18 Tor y servicios ocultos ● Existen sitios del tipo http://abcxyz.onion que son accesibles solo a través de Tor ● La comunicación es siempre cifrada ● Parte importante de la Deepweb, Darknet, etc. ● El servidor nunca sabe desde donde se conectan los clientes ● La ubicación del servidor es secreta ● Wikileaks: http://wlupld3ptjvsgwqw.onion 9/18 Tor permite ocultar metadata 10/18 La NSA y Tor ● Tor es financiado principalmente por el gobierno de EEUU ● Tor es software libre ● Tor es una red con miles de nodos ● Los nodos se seleccionan de forma aleatoria en el cliente ● Según presentación filtrada por Snowden para la NSA “Tor Stincks” 11/18 La NSA y Tor https://edwardsnowden.com/2013/10/04/tor-stinks-presentation/ -

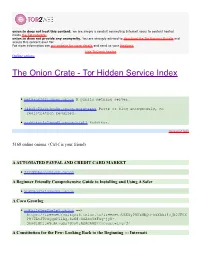

The Onion Crate - Tor Hidden Service Index

onion.to does not host this content; we are simply a conduit connecting Internet users to content hosted inside the Tor network.. onion.to does not provide any anonymity. You are strongly advised to download the Tor Browser Bundle and access this content over Tor. For more information see our website for more details and send us your feedback. hide Tor2web header Online onions The Onion Crate - Tor Hidden Service Index nethack3dzllmbmo.onion A public nethack server. j4ko5c2kacr3pu6x.onion/wordpress Paste or blog anonymously, no registration required. redditor3a2spgd6.onion/r/all Redditor. Sponsored links 5168 online onions. (Ctrl-f is your friend) A AUTOMATED PAYPAL AND CREDIT CARD MARKET 2222bbbeonn2zyyb.onion A Beginner Friendly Comprehensive Guide to Installing and Using A Safer yuxv6qujajqvmypv.onion A Coca Growlog rdkhliwzee2hetev.onion ==> https://freenet7cul5qsz6.onion.to/freenet:USK@yP9U5NBQd~h5X55i4vjB0JFOX P97TAtJTOSgquP11Ag,6cN87XSAkuYzFSq-jyN- 3bmJlMPjje5uAt~gQz7SOsU,AQACAAE/cocagrowlog/3/ A Constitution for the Few: Looking Back to the Beginning ::: Internati 5hmkgujuz24lnq2z.onion ==> https://freenet7cul5qsz6.onion.to/freenet:USK@kpFWyV- 5d9ZmWZPEIatjWHEsrftyq5m0fe5IybK3fg4,6IhxxQwot1yeowkHTNbGZiNz7HpsqVKOjY 1aZQrH8TQ,AQACAAE/acftw/0/ A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace ufbvplpvnr3tzakk.onion ==> https://freenet7cul5qsz6.onion.to/freenet:CHK@9NuTb9oavt6KdyrF7~lG1J3CS g8KVez0hggrfmPA0Cw,WJ~w18hKJlkdsgM~Q2LW5wDX8LgKo3U8iqnSnCAzGG0,AAIC-- 8/Declaration-Final%5b1%5d.html A Dumps Market - Dumps, Cloned Cards, -

The Dark Side of the Web: ISIL’S One-Stop Shop? by Beatrice Berton

30 2015 UNCREDI T ED/AP/S I PA The dark side of the web: ISIL’s one-stop shop? by Beatrice Berton In addition to its territorial expansion, the Islamic as it is inaccessible to most but navigable for the State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) has also em- initiated few – and it is completely anonymous. barked on a new campaign in the realm of cyber warfare. While Western law enforcement agen- The most popular means of accessing and navigat- cies are already tackling ISIL’s propaganda, train- ing the Dark Web is to use a Tor browser. Conceived ing programmes and recruitment drives on the by the US Navy as a means of protecting sensitive mainstream web, the US Cyber Command has ex- communications, the Tor browser allows users to pressed its concerns over the growing penetration hide their IP address and activity through a world- of terrorist organisations into the so-called Dark wide network of computers and different layers Web, the hidden underbelly of the online world’s of encryption (like the layers of an onion), which Deep Web. guarantee their anonymity. Hidden services and marketplaces are listed on index pages such as the The web we know and use every day, made up of Hidden Wiki and are accessible only through Tor. websites accessible through conventional search Silk Road, a notorious online marketplace which engines such as Google, is referred to as the Surface sells drugs and weapons, was shut down by the Web. Few web users are aware that there is a Deep FBI in 2013, but a variety of black markets such Web, a larger (about 500 times) section of the as Agora, Evolution and AlphaBay soon filled the web consisting of websites, networks and online void and welcomed many of the buyers and sellers content which are not indexed by search engines. -

The Digital Black Market and Drugs: Do You Know Where Your Children Are?

MOJ Addiction Medicine & Therapy Opinion Open Access The digital black market and drugs: do you know where your children are? Opinion Volume 5 Issue 6 - 2018 Parents, do you know where your children are? The public service Melissa Vayda announcement (PSA) of our youth takes on a whole new meaning Educational Affairs Penn State College of Medicine, University in the era of the Internet.1 Our children are often right there, in our Park, USA own homes doing the very things we want to protect them from–and we know exactly where they are – but we don’t know what they are Correspondence: Melissa Vayda, Director, Educational Affairs Penn State College of Medicine, University Park, USA, 2 doing. We don’t even know what they could be doing! When was the Email last time your teen received a package in the mail? These days with amazon, eBay,3 and internet commerce, it is commonplace to receive Received: March 12, 2018 | Published: November 15, 2018 packages in the mail and you may think nothing of it. Read further and you may start checking that packages.4 Have you heard of the Darknet? Do you know what cryptocurrency is? Have you ever heard of TOR? These are very compelling reasons for parents to learn and embrace new technology.5 If you do not Unfortunately, this is just the tip of the iceberg where drugs on understand it, you may not be able to stop it. These three things are the the Darknet are concerned. ‘Lesser’ drugs are often laced with a gateway to the digital black market for drugs, guns, and many other stringer synthetic opioid, fentanyl, which is the fastest-growing cause illegal products and services.6 The Darknet and the digital black market of overdoses nationwide.18Just a few flakes of fentanyl can be fatal.