Housing – Critical Futures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOM Magazine No

2020 DOM magazine 04 December The Art of Books and Buildings The Cities of Tomorrow Streets were suddenly empty, and people began to flee to the countryside. The corona virus pandemic has forced us to re- think urban design, which is at the heart of this issue. From the hotly debated subject of density to London’s innovative social housing through to Berlin’s creative spaces: what will the cities of the future look like? See pages 14 to 27 PORTRAIT The setting was as elegant as one would expect from a dig- Jean-Philippe Hugron, nified French institution. In late September, the Académie Architecture Critic d’Architecture – founded in 1841, though its roots go back to pre- revolutionary France – presented its awards for this year. The Frenchman has loved buildings since The ceremony took place in the institution’s rooms next to the childhood – the taller, the better. Which Place des Vosges, the oldest of the five ‘royal squares’ of Paris, is why he lives in Paris’s skyscraper dis- situated in the heart of the French capital. The award winners trict and is intrigued by Monaco. Now he included DOM publishers-author Jean-Philippe Hugron, who has received an award from the Académie was honoured for his publications. The 38-year-old critic writes d’Architecture for his writing. for prestigious French magazines such as Architecture d’au jourd’hui and Exé as well as the German Baumeister. Text: Björn Rosen Hugron lives ten kilometres west of the Place des Vosges – and architecturally in a completely different world. -

Rückkehr Der Wohnmaschinen

Maren Harnack Rückkehr der Wohnmaschinen Architekturen | Band 10 Maren Harnack (Dr.-Ing.) studierte Architektur, Stadtplanung und Sozialwis- senschaften in Stuttgart, Delft und London. Sie arbeitete als wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin an der HafenCity Universtät in Hamburg und ist seit 2011 Pro- fessorin für Städtebau an der Fachhochschule Frankfurt am Main. Daneben ist sie freie Stadtplanerin, freie Architektin, wirkte an zahlreichen Forschungspro- jekten mit und publiziert regelmäßig in den Fachmedien. Maren Harnack Rückkehr der Wohnmaschinen Sozialer Wohnungsbau und Gentrifizierung in London Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde im Herbst 2010 von der HafenCity Universität Hamburg als Dissertation angenommen. Gutachter waren Prof. Dr. sc. techn. ETH Michael Koch und Prof. Dr. phil. Martina Löw. Die mündliche Prüfung fand am 21. Oktober 2010 statt. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © 2012 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Die Verwertung der Texte und Bilder ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages ur- heberrechtswidrig und strafbar. Das gilt auch für Vervielfältigungen, Überset- zungen, Mikroverfilmungen und für die Verarbeitung mit elektronischen Sys- temen. Umschlaggestaltung: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Umschlagabbildung: Martin Kohler Lektorat: Gabriele Roy, Ingar Milnes, Bernd Harnack Satz: Maren Harnack Druck: Majuskel Medienproduktion -

Exploring the Housing Potential of Large Sites 2000

Sustainable Residential Quality Exploring the Housing Potential of Large Sites Llewelyn-Davies Sustainable Residential Quality Exploring the Housing Potential of Large Sites Llewelyn-Davies in association with Urban Investment Metropolitan Transport Research Unit January 2000 Acknowledgements The study team would like to thank the Steering Group for their help, support and guidance throughout the study, and acknowledge the particular insights provided by the expert panel which was formed to advise the study. Steering Group The Steering Group was chaired by John Lett of LPAC and included: Debbie McMullen LPAC Jeni Fender LPAC Jennifer Walters LPAC Tony Thompson Government Office for London Samantha Scougall Government Office for London Peter Livermore London Transport Dave Norris Housing Corporation Duncan Bowie Housing Corporation Expert Panel Professor Kelvin McDonald Director,National Housing and Town Planning Council Martin Jewell Planning Director,Fairview Homes Jeremy Peter Land and Planning Officer,House Builders Federation John MacFarlane Development Manager,Circle Thirty Three Housing Trust Ltd Paul Finch Editor,Architects Journal Clare Chettle Head of Development, East Thames Housing Group Paul Cooke Development Director,Laing Partnership Housing Llewelyn-Davies Study Team Study Director Dr Patrick Clarke Study Managers Andrew Bayne and Christina von Borcke Urban Design Neil Parkyn Christina von Borcke Paul Drew Harini Septiana Alan Simpson Arja Lehtimaki Planning Policy Iona Cameron Transport Keith Buchan (MTRU) Chris Wood (MTRU) Housing Development Advice John Goulding (Urban Investment) Graphics and Production Bally Meeda Christina von Borcke Edmund Whitehouse Helen Brunger Perspectives Richard Carman Llewelyn-Davies II Contents List of Figures IV Part III Conclusions & Implications for Policy & Practice 109 Study Overview V 7. -

6 5 2 1 3 7 9 8Q Y T U R E W I O G J H K F D S

i s 8 7q a 3 CITY 5 e TOWER HAMLETS k p 4 1 u rf 6w y 2 9 g j t do h RADICAL HOUSING LOCATIONS Virtual Radical Housing Tour for Open House Hope you enjoyed the virtual tour. Here’s a list of the sites we visited on the tour with some hopefully useful info. Please see the map on the website https://www.londonsights.org.uk/ and https://www.morehousing.co.uk/ ENJOY… No Site Year Address Borough Built VICTORIAN PHILANTHROPISTS Prince Albert’s Model Cottage 1851 Prince Consort Lodge, Lambeth Built for the Great Exhibition 1851 and moved here. Prince Albert = President of Society for Kennington Park, Improving the Condition of the Labouring Classes. Prototype for social housing schemes. Kennington Park Place, 4 self-contained flats with inside WCs. Now HQ for Trees for Cities charity. London SE11 4AS Lambeth’s former workhouse – now the Cinema Museum 1880s The Cinema Museum Lambeth Charlie Chaplin sent here 1896 with mother and brother. Masters Lodge. 2 Dugard Way, Prince's, See website for opening times http://www.cinemamuseum.org.uk/ London SE11 4TH Parnell House 1850 Streatham Street Camden Earliest example of social housing in London. Same architect (Henry Roberts) as Model Cottage in Fitzrovia, London stop 1. Now owned by Peabody housing association (HA). Grade 2 listed. WC1A 1JB George Peabody statue Royal Exchange Avenue, City of London George Peabody - an American financier & philanthropist. Founded Peabody Trust HA with a Cornhill, charitable donation of £500k. London EC3V 3NL First flats built by Peabody HA 1863 Commercial Street Tower Now in private ownership London E1 Hamlets Peabody’s Blackfriars Road estate 1871 Blackfriars Road Southwark More typical ‘Peabody’ design. -

Orpington from the Great War

ORPINGTON FROM THE GREAT WAR. m m wm 1 st: mm mmm-m* m m ~7V, *? O S ' tfjcytxd MR & MRS BILL MORTON 205 CROFTON ROAD ORPINGTON, KENT # BR6 8JE PHONE 0689-55409 IN ■‘REMEMBRANCE OF • BRA VE ■ MEN ■ WHO ‘DIED ■ FOR ■ THEIR ^ COUNTRY M C M X I X & THEY • DIED • FOR • ENGLAND • BRAVELY • DARED * THEIR • LIVES • THAT • LIBERTY • MIGHT • LIVE • TO • PEACE • THE • PATHWAYS • THEY • PREPARED • THY • PEACE • AND • LIGHT • LORD • TO • THEM - GIVE • J.F.T. PRO • P ATRIA- PERIERE • DOMI • MODO • VIVERET- ALMA LIBERTAS • VITAM • POSTHABUERE • SUAM • MUNIVERE • VIAM • FUSO • SED • SANGUINE • PACI PAX • HIS • OMNIPOTENS • SIT • TUA • SIT • REQUIES E J.R . li, ^he Qreat War: 1914 — 18. A TRIBUTE ‘T o the fKCe of Who T)ied in ^Uhe Ontario ilitary Hospital, Orpington, Kent, England, and is buried in Orpington Churchyard. From AND FRIENDS IN ORPINGTON, KENT, ENGLAND. To .................................................................................... No land is dearer to man or woman than that which witnessed the ■ passing of their dead and which holds the remains of those they love. The body of your dear one rests in the peaceful village of Orpington, in the shadow of the old Church which for nearly a thousand years has witnessed the coming and going of men and women of the district in almost every chapter of the long history of England. He lies with his fellow soldiers, in a sheltered corner of the Church yard carfeted with grass and fringed with trees. Above, in the spring time the skylarks sing all day, and the warm Summer nights are filled with the song of the nightingale, and are rich with the scent of flowers. -

Community Food Initiatives in London by Shumaisa S. Khan

Food Sovereignty Praxis beyond the Peasant and Small Farmer Movement: Community Food Initiatives in London by Shumaisa S. Khan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Natural Resources and Environment) in the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Dorceta E. Taylor, Chair Associate Professor Larissa S. Larsen Associate Professor Gavin M. Shatkin Adjunct Professor Gloria E. Helfand © Shumaisa S. Khan 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are so many people who have made this endeavor possible. I am very grateful to my advisor, Dorceta Taylor, for providing guidance and support from even before I stepped foot on campus. You have been a wonderful advisor, mentor, and friend, and have given me invaluable advice throughout my studies. Thank you also to Gloria Helfand, Larissa Larsen, and Gavin Shatkin for helping me to find a focus amidst the multiple dimensions in this study. I am also grateful to Rackham for funding my education and for support after a family emergency in the last few months; the Center for the Education for Women for a research grant and support in the last few months; and grants from the School of Natural Resources and Environment. Danielle Gwynne and Giselle Kolenic from CSCAR-thank you for your help with GIS. Jennifer Taylor, Diana Woodworth, and Kimberly LeClair in OAP- thank you for all of your assistance over the years. Knowledge Navigation Center folks- you are indispensable in getting the correct formatting. Of course, I am immensely grateful for all of the participants who took the time to share their perspectives with me and to contributors to Open Street Map and open source work generally for making knowledge and knowledge creation more accessible. -

Social Housing in the UK and US: Evolution, Issues and Prospects

Social Housing in the UK and US: Evolution, Issues and Prospects Michael E. Stone, Ph.D. Atlantic Fellow in Public Policy Visiting Associate, Centre for Urban and Community Research, Goldsmiths College, University of London Professor of Community Planning and Public Policy University of Massachusetts Boston October 2003 Support and Disclaimer: This research was made possible through an Atlantic Fellowship in Public Policy, funded by the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and administered by the British Council. Additional support has been provided by the Centre for Urban and Community Research, Goldsmiths College, University of London; and the John W. McCormack Institute for Public Affairs, University of Massachusetts Boston. The views expressed herein are not necessarily those of the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the British Council, Goldsmiths College, or the University of Massachusetts Boston. Acknowledgements: Community Activists: Malcolm Cadman, Bill Ellson, Steve Hurren, Jean Kysow, Jessica Leech, Shirley Mucklow, Pete Pope, Jess Steele Housing Professionals: Keith Anderson, John Bader, Alan Bonney, Lorraine Campbell, Simon Cribbens, Emyr Evans, Barbara Gray, Pat Hayes, Andy Kennedy, Colm McCaughley, David Orr, Steve Palmer, Emma Peters, Roland Smithies, Louise Spires, Sarah Thurman Goldsmiths College CUCR Staff: Les Back, Ben Gidley, Paul Halliday, Roger Hewitt, Carole Keegan, Michael Keith, Azra Khan, Marjorie Mayo, Neil Spicer, Chenli Vautier, Bridget Ward © Copyright, 2003, Michael E. Stone. All rights reserved. -

16 06 Futuro RL

INNOVATION IN 1960s ARCHITECTURE The London County Council Architects’ Department housing REBUILDING POLICY URBANISM County of nationalisation London Plan pedagogy POLITICS school meals Survey of London Festival of Britain communities ECONOMICS ethos EDUCATION This Is Tomorrow kitchen provision schools collaboration systems building ART commissioning INDUSTRY environmental fabrication concerns material innovation rationing housing REBUILDING POLICY URBANISM County of nationalisation London Plan pedagogy POLITICS school meals Survey of London Festival of Britain communities ECONOMICS ethos EDUCATION This Is Tomorrow kitchen provision schools collaboration systems building ART commissioning INDUSTRY environmental fabrication concerns material innovation rationing GENEALOGY WATNEY MARKET ESTATE1968 County of London Plan Royal Festival Hall Alton Estate CITY OF LONDON Pimlico School County Hall Westminster Bridge Road, London SE1 7PB Alison and Peter Smithson Group One: Theo Crosby, Germano Facetti, William Turnbull, Edward Wright Group Two: Richard Hamilton, John McHale, John Voelcker Group Three: J. D. H. Catleugh, James Hull, Leslie Thornton Group Four: Anthony Jackson, Sarah Jackson, Emilio Scanavino Group Five: John Ernest, Anthony Hill, Denis Williams Group Six: Eduardo Paolozzi, Alison and Peter Smithson, Nigel Henderson Group Seven: Victor Pasmore, Ernö Goldfinger, Helen Phillips Group Eight: James Stirling, Michael Pine, Richard Matthews Group Nine: Kenneth Martin, Mary Martin and John Weeks Group Ten: Robert Adams, Frank Newby, Peter Carter, Colin St. John Wilson Group Eleven: Adrian Heath, John Weeks Group Twelve: Lawrence Alloway, Geoffrey Holroyd, Toni del Renzio *commissioned by LCC *previously employed within Department GROUP TEN “The aim of our collaboration has been to explore the ground that is common to architecture and sculpture We believe that the development of such collaborations may lead to a more integrated human environment” This is Tomorrow exhibition catalogue pub. -

Case Studies in Interwar Housing at Welwyn Garden City, Becontree and St

Complete Communities or Dormitory Towns? Case Studies in Interwar Housing at Welwyn Garden City, Becontree and St. Helier Matthew David Benjamin Submitted to the University of Hertfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts by Research January 2016 Revised August 2016 Supervisors: Dr. Katrina Navickas, School of Humanities Dr. Susan Parham, School of Humanities 1 Abstract Housing has always been a paramount issue; in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century attempts were made to revolutionise the problem of poor quality houses and the accompanying poor quality of life. This was set against the backdrop of the industrial expansion of the urban metropolis; with possible solutions moving towards decentralisation of the most overpopulated areas. Arguably the most significant steps to remedy the housing issue were made in the interwar period with the development of the second Garden City at Welwyn and the London County Council out of county estates. This thesis focuses on the development of community at the three developments chosen as case studies: Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire and the Becontree Estate in Essex and the St. Helier Estate in Surrey. Key points of analysis were identified and investigated using a range of sources in order to come to a just conclusion. It was found that community values developed substantially over the early stages of growth, not without some examples of friction between existing and new residents. The development of public facilities such as churches, schools, public houses, community centres aided the progression of core community values through all three case studies. The development of these community hubs supported the progression of civic cohesion and pride, thus making the residents feel comfortable in their new surroundings and part of something bigger than themselves. -

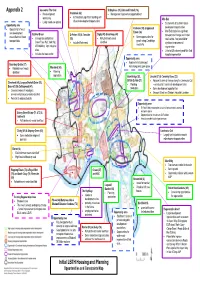

Initial LBTH Housing and Planning Appendix 2

Appendix 2 Gas works/ The Oval St Stephens (31) Libra and Parnell (18), • Re-development Cranbrook (42) • Management improvement opportunities? • Architecturally significant buildings will opportunity Mile End influence development opportunities • Likely mixed-use options • St Clements & Southern Grove Opportunity area development opportunities • Opportunity to focus Parkview (53) & Approach • Mile End station is a significant new development Estate (34) Bethnal Green St Peters (55) & Teesdale Digby (43) Greenways (44) transport interchange and limited around Bethnal Green • Some opportunities for • Incorporates old Bethnal (56) • Refurbishment needs retail centre - has potential for transport links growth along Cambridge Green Town Hall, York Hall, • Includes Rushmead identified significant improvement / Health Rd LEB building, light industrial regeneration sites • Links to QM university and Mile End • Includes the town centre Hospital regeneration Opportunity area • Improve links to transport Boundary Estate (37) interchange and open space • Refurbishment needs Mansford (50) identified • Planning application Bow Bridge (20), Lincoln (27) & Coventry Cross (22) British Estate (21) • Adjacent to area of change along the Limehouse Cut Cleveland (40), Longnor/Norfolk/Osier (52), • Planning – ex-industrial / canal side development sites Bancroft (36) Collingwood (41) application • Some development opportunities • Cleveland external redesign & • Empson Street is a Strategic Industrial Location environmental/security needs identified • Potential -

Patrimoine Européen Des Frontières – Points De Rupture, Espaces Partagés

DIVIDING LINES 7/02/11 17:08 Page 2 Patrimoine européen S’il est le reflet en Europe des périodes d’ouverture, de paix et de prospérité, le patrimoine culturel est également celui des phases de tension vécues sur notre continent. La charge des frontières – Points identitaire associée aux patrimoines de nos pays, depuis la construction des Etats tagés nationaux aux XIXe et XXe siècles, peut s’interpréter comme une masse ambivalente, un de rupture, espaces partagés potentiel à la fois d’entente et de conflit. La frontière est un lieu critique : on se situe d’un côté ou de l’autre. La frontière sépare et démarque les territoires et les identités. Mais elle attire aussi et séduit, car elle est le espaces par lieu de l’entre-deux, espace d’ouverture et de rencontres inédites. C’est sans doute sur les frontières qu’ont le plus de chance d’émerger ces identités plurielles riches de mille facettes et porteuses d’une surprenante créativité. L’identité européenne pourrait en upture, définitive être le plus perceptible en ces zones critiques où des influences diverses se fécondent mutuellement et où ce que l’on croyait impossible devient imaginable. Les textes du livre Patrimoine européen des frontières – Points de rupture, espaces partagés relient le thème du patrimoine à celui des frontières, qu’il s’agisse des frontières géographiques ou des frontières de l’imaginaire. Ils étudient les paysages frontaliers, les vestiges d’anciennes lignes de tension et de barrières fortifiées désormais sans usage. Ils évoquent également les nouvelles frontières urbaines issues du regroupement de populations en groupes ethniques ou d’affinités dans les grandes métropoles de l’Europe. -

Bethnal Green Gardens Conservation Area (Area 1) Page 1 of 18 Appendix B – Draft Conservation Area Appraisals and Management Guidelines

Appendix A LONDON BOROUGH OF TOWER HAMLETS CONSERVATION AREAS TOWER HAMLETS 0 500 1,000 Metres 17 35 31 38 36 24 41 1 13 10 7 37 22 33 42 30 32 27 4 5 12 48 14 40 23 44 43 50 46 9 34 6 49 39 45 8 47 25 3 26 28 21 15 19 18 20 2 16 Legend Conservation Areas for which Appraisals and Management Plans have been 29 prepared in 2006/07 11 1. Bethnal Green Gardens 18. The Tower 35. Roman Road Market 2. Wapping Pierhead 19. West India Dock 36. Medway 3. St George's Town Hall 20. Wapping Wall 37. Clinton Road 4. Elder Street 21. St Paul's Church 38. Fairfield Road 5. Brick Lane and Fournier Street 22. Boundary Estate 39. Lowell Street 6. Albert Gardens 23. Ford Square 40. London Hospital 7. Tomlins Grove 24. Jesus Hospital Estate 41. Globe Road 8. St Annes Church 25. All Saints Church Poplar 42. St Peter's 9. York Square 26. St Mathias Church Poplar 43. Langdon Park 10. Tredegar Square 27. Ropery Street 44. Wentworth Street 11. Island Gardens 28. Naval Row 45. St Frideswide's 12. Stepney Green 29. Chapel House 46. Myrdle Street 13. Three Mills 30. Tower Hamlets Cemetery 47. Lansbury 14. Artillary Passage 31. Driffield Road 48. Whitechapel Market 15. Narrow Street 32. Swaton Road 49. Balfron Tower 16. Coldharbour 33. Carlton Square 50. Whitechapel High 17. Victoria Park 34. Commercial Road Street This map is indicative only and is not a planning document.