UN Assistance Mission for Iraq 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Abu Ghraib District ( ( (

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Abu Ghraib District ( ( ( ( ( ( Idressi Hay Al Askari - ( - 505 Turkey hoor Al basha IQ-P08985 Hamamiyat IQ-P08409 IQ-P08406 Mosul! ! ( ( Erbil ( Syria Iran Margiaba Samadah (( ( ( Baghdad IQ-P08422 ( IQ-P00173 Ramadi! ( ( !\ Al Hay Al Qaryat Askary ( Hadeb Al-Ru'ood Jordan Najaf! IQ-P08381 IQ-P00125 IQ-P00169 ( ( ( ( ( Basrah! ( Arba'at AsSharudi Arabia Kuwait Alef Alf (14000) Albu Khanfar Al Arba' IQ-P08390 IQ-P08398 ( Alaaf ( ( IQ-P00075 ( Al Gray'at ( ( IQ-P08374 ( ( 336 IQ-P08241 Al Sit Alaaf ( (6000) Sabi' Al ( Sabi Al Bur IQ-P08387 Bur (13000) - 12000 ( ( Hasan Sab'at ( IQ-P08438 IQ-P08437 al Laji Alaaf Sabi' Al ( IQ-P00131 IQ-P08435 Bur (5000) ( ( IQ-P08439 ( Hay Al ( ( ( Thaman Alaaf ( Mirad IQ-P08411 Kadhimia District ( as Suki Albu Khalifa اﻟﻛﺎظﻣﯾﺔ Al jdawil IQ-P08424 IQ-P00074 Albu Soda ( Albo Ugla ( (qnatir) ( IQ-P00081 village ( IQ-P00033 Al-Rufa ( IQ-D040 IQ-P00062 IQ-P00105 Anbar Governorate ( ( ( اﻻﻧﺑﺎر Shimran al Muslo ( IQ-G01 Al-Rubaidha IQ-P00174 Dayrat IQ-P00104 ar Rih ( IQ-P00120 Al Rashad Al-Karagul ( Albu Awsaj IQ-P00042 IQ-P00095 IQ-P00065 ( ( ( Albo Awdah Bani Zaid Al-Zuwayiah ( Ad Dulaimiya ( Albu Jasim IQ-P00060 Hay Al Halabsa - IQ-P00117 IQ-P00114 ( IQ-P00022 Falluja District ( ( ( - Karma Uroba Al karma ( Ibraheem ( IQ-P00072 Al-Khaleel اﻟﻔﻠوﺟﺔ Al Husaiwat IQ-P00139 IQ-P00127 ) ( ( Halabsa Al-Shurtan IQ-P00154 IQ-P00031 Karma - Al ( ( ( ( ( ( village IQ-P00110 Ash Shaykh Somod ( ( IQ-D002 IQ-P00277 Hasan as Suhayl ( IQ-P00156 subihat Ibrahim ( IQ-P08189 Muhammad -

Iraq SITREP 2015-5-22

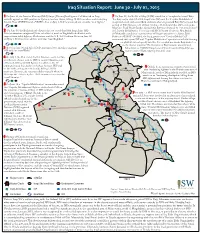

Iraq Situation Report: June 30 - July 01, 2015 1 On June 30, the Interior Ministry (MoI) Suqur [Falcons] Intelligence Cell directed an Iraqi 7 On June 29, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (AAH) stated that it “completely cleared” Baiji. airstrike against an ISIS position in Qa’im in western Anbar, killing 20 ISIS members and destroying e Baiji mayor stated that IA, Iraqi Police (IP), and the “Popular Mobilization” Suicide Vests (SVESTs) and a VBIED. Also on July 1, DoD announced one airstrike “near Qa’im.” recaptured south and central Baiji and were advancing toward Baiji Renery and had arrived at Albu Juwari, north of Baiji. On June 30, Federal Police (FP) commander Maj. Gen. Raed Shakir Jawdat claimed that Baiji was liberated by “our armed forces” 2 On June 30, the Baghdadi sub-district director stated that 16th Iraqi Army (IA) and Popular Mobilization Commission (PMC) Deputy Chairman Abu Mahdi Division members recaptured Jubba sub-district, north of Baghdadi sub-district, with al-Muhandis stated that “security forces will begin operations to cleanse Baiji support from tribal ghters, IA Aviation, and the U.S.-led Coalition. Between June 30 Renery of [ISIS].” On July 1, the Iraqi government “Combat Media Cell” and July 1, DoD announced four airstrikes “near Baghdadi.” announced that a joint ISF and “Popular Mobilization” operation retook the housing complex but did not specify whether the complex was inside Baiji district or Dahuk on the district outskirts. e liberation of Baiji remains unconrmed. 3 Between June 30 and July 1 DoD announced two airstrikes targeting Meanwhile an SVBIED targeted an IA tank near the Riyashiyah gas ISIS vehicles “near Walid.” Mosul Dam station south of Baiji, injuring the tank’s crew. -

Reframing Social Fragility in Iraq

REFRAMING SOCIAL FRAGILITY IN AREAS OF PROTRACTED DISPLACEMENT AND EMERGING RETURN IN IRAQ: A GUIDE FOR PROGRAMMING NADIA SIDDIQUI, ROGER GUIU, AASO AMEEN SHWAN International Organization for Migration Social Inquiry The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Cover Image: Kirkuk, Iraq, June 2016, Fragments in Kirkuk Citadel. Photo Credit: Social Inquiry. 2 Reframing Social Fragility In Areas Of Protracted Displacement And Emerging Return In Iraq Nadia Siddiqui Roger Guiu Aaso Ameen Shwan February 2017 3 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research and report were designed and written by Social Inquiry, a research group that focuses on post-conflict and fragile societies. The authors are Nadia Siddiqui, Roger Guiu, and Aaso Ameen Shwan. This work was carried out under the auspices of the International Organization for Migration’s Community Revitalization Program in Iraq and benefitted significantly from the input and support of Ashley Carl, Sara Beccaletto, Lorenza Rossi, and Igor Cvetkovski. -

Report on Iraq's Compliance with the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

Report on Iraq's Compliance with the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination SUBMITTED TO THE UN COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION Iraqi High Commission for Human Rights (IHCHR) Baghdad 2018 1 Table of Contents Introduction: …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 The Convention in Domestic Law (Articles 1, 3 & 4): ……………………………………………………………..3 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 Process of democratization and Inter-Ethnic Relations (Articles 2 - 7): ……………………………..…. 3 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Effective Protection of Ethnic and Religious-Ethnic Groups against Acts of Racial Discrimination (Articles 2, 5 & 6): ………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Statistical Data Relating to the Ethnic Composition of the Population (Articles 1 & 5): ………….9 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..10 Legal Framework against Racial Discrimination (Articles 2-7): ……………………………………………. 10 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 11 National Human Rights Bodies to Combat Racial Discrimination (Articles 2-7): ………………….. 11 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..12 The Ethnic Composition of the Security and Police Services (Articles 5 & 2): ……………………… 12 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..13 Minority Representation in Politics (Articles 2 & 5): …………………………………………………………… 13 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

12 NOV 07 Crossed Sabers:Crossed Sabers Jan 20.Qxd.Qxd

Iraqi Army “Junior Hero” Red Legs Vie to be Best Iraqi Emergency Visits School Field Artillery Crew in Top Responders Work Gun Competition Together Page 7 Page 16 Page 20 Volume I, Issue 25 Telling the MND-Baghdad Story Monday, Oct. 12, 2007 Photo by Maj. Michael J. Indovina Troops of Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 18th Military Police Brigade await the departure on their flight, a Air Force aircraft into Baghdad International Airport. Brigade Arrives in Iraq By Sgt. Daniel D. Blottenberger 18th Military Police Brigade Public Affairs CAMP VICTORY, Iraq— In eager silence Soldiers of the Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 18th Military Police Brigade walked through manmade paths aligned with barriers on their way from Baghdad International Airport to Camp Victory here. Soldiers from the 18th Military Police Brigade deployed from Mannheim Germany, recently completed their final stage of in pro- cessing and training into the Middle Eastern theater in Kuwait, and arrived here in Iraq to their final destination for its upcoming 15 month deployment mission. The final training and in-processing in Kuwait focused on tasks specific for this area of operation. (Photo by Cpl. Nathan Hoskins, 1st ACB, 1st Cav. Div. Public Affairs) “From the stories I’ve heard, I expected the area to be in chaos with bombs going off everywhere, but once I got here I found that doing my job as a personnel clerk was not much different from ‘Witch Doctors’ Begin Journey Home what I am used to doing elsewhere,” said Spc. Anthony Henderson, With 15 months of medical evacuation missions behind them, Soldiers from Company C, 2nd a native of Memphis, Tenn., and a human resources specialist with “Lobo” Battalion, 227th Aviation Regiment, 1st Air Cavalry Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, load the unit. -

Health Sector

Electricity Sector Project's name Location Capacity Province 1 Al-Yusfiya Gas Al-Yusfiya 1500 Mega Baghdad Station Project Watt (Combined Cycle) - Communication Sector None Health Sector No Project’s Name Type of Province Investment Opportunities 1. General hospital, capacity: (400) beds- New Baghdad/ Al-Rusafa/ 15 buildings ( 12 main healthcare construction Bismayah New City centers / (1) typical healthcare center, specialized medical center). 2. Specialized cancer treatment center New Baghdad, Al Karkh and Al- construction Rusafa 3. Arabic Child Hospital in Al-Karkh (50 New Baghdad/ Al-Karkh beds) construction 4. 3-4 Drugs and medical appliances New Baghdad, Al Karkh and Al- factory. construction Rusafa 5. 1 Sterility and fertility hospital, New Baghdad in Al Karkh and Capacity: (50 beds) construction Al-Rusafa 6. 1 Specialized ophthalmology hospital New Baghdad , Al Karkh and Al- Capacity : ( 50 beds ) construction Rusafa 7. 1 Specialized cardiac surgery hospital New Baghdad, Al Karkh and Al- capacity : (100 beds) construction Rusafa 8. Specialized Plastic surgery hospital New Baghdad, Al Karkh and Al- (50 beds) construction Rusafa 9. 2-3 hydrogen peroxide (pure New Baghdad, Al Karkh and Al- O2)Plant Construction Rusafa 10. Complete medical city New Baghdad , Al Karkh and Al- construction Rusafa 11. 4 General hospitals , capacity: 100 bed New Baghdad, Al-Karkh and Al- each construction Rusafa 12. 4 Specialized medical centers, New Baghdad , Al-Karkh and Al- capacity : (50 bed) construction Rusafa Housing and Infrastructure sector No. Project name Location allocatd Province area 1. Establishment of Housing Complex (According Al-Tarimiyah 5609 Baghdad to investor’s economic visibility). District/Abo-Serioel Dunam and Quarter. -

Mcallister Bradley J 201105 P

REVOLUTIONARY NETWORKS? AN ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN IN TERRORIST GROUPS by Bradley J. McAllister (Under the Direction of Sherry Lowrance) ABSTRACT This dissertation is simultaneously an exercise in theory testing and theory generation. Firstly, it is an empirical test of the means-oriented netwar theory, which asserts that distributed networks represent superior organizational designs for violent activists than do classic hierarchies. Secondly, this piece uses the ends-oriented theory of revolutionary terror to generate an alternative means-oriented theory of terrorist organization, which emphasizes the need of terrorist groups to centralize their operations. By focusing on the ends of terrorism, this study is able to generate a series of metrics of organizational performance against which the competing theories of organizational design can be measured. The findings show that terrorist groups that decentralize their operations continually lose ground, not only to government counter-terror and counter-insurgent campaigns, but also to rival organizations that are better able to take advantage of their respective operational environments. However, evidence also suggests that groups facing decline due to decentralization can offset their inability to perform complex tasks by emphasizing the material benefits of radical activism. INDEX WORDS: Terrorism, Organized Crime, Counter-Terrorism, Counter-Insurgency, Networks, Netwar, Revolution, al-Qaeda in Iraq, Mahdi Army, Abu Sayyaf, Iraq, Philippines REVOLUTIONARY NETWORK0S? AN ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN IN TERRORIST GROUPS by BRADLEY J MCALLISTER B.A., Southwestern University, 1999 M.A., The University of Leeds, United Kingdom, 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY ATHENS, GA 2011 2011 Bradley J. -

Iraq: Post-Saddam Governance and Security

Order Code RL31339 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: Post-Saddam Governance and Security Updated March 29, 2006 Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: Post-Saddam Governance and Security Summary Operation Iraqi Freedom succeeded in overthrowing Saddam Hussein, but Iraq remains violent and unstable because of Sunni Arab resentment and a related insurgency, as well as growing sectarian violence. According to its November 30, 2005, “Strategy for Victory,” the Bush Administration indicates that U.S. forces will remain in Iraq until the country is able to provide for its own security and does not serve as a host for radical Islamic terrorists. The Administration believes that, over the longer term, Iraq will become a model for reform throughout the Middle East and a partner in the global war on terrorism. However, mounting casualties and costs — and growing sectarian conflict — have intensified a debate within the United States over the wisdom of the invasion and whether to wind down U.S. involvement without completely accomplishing U.S. goals. The Bush Administration asserts that U.S. policy in Iraq is showing important successes, demonstrated by two elections (January and December 2005) that chose an interim and then a full-term National Assembly, a referendum that adopted a permanent constitution (October 15, 2005), progress in building Iraq’s security forces, and economic growth. While continuing to build, equip, and train Iraqi security units, the Administration has been working to include more Sunni Arabs in the power structure, particularly the security institutions; Sunnis were dominant during the regime of Saddam Hussein but now feel marginalized by the newly dominant Shiite Arabs and Kurds. -

The Euphrates River: an Analysis of a Shared River System in the Middle East

/?2S THE EUPHRATES RIVER: AN ANALYSIS OF A SHARED RIVER SYSTEM IN THE MIDDLE EAST by ARNON MEDZINI THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON September 1994 ProQuest Number: 11010336 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010336 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract In a world where the amount of resources is constant and unchanging but where their use and exploitation is growing because of the rapid population growth, a rise in standards of living and the development of industrialization, the resource of water has become a critical issue in the foreign relations between different states. As a result of this many research scholars claim that, today, we are facing the beginning of the "Geopolitical era of water". The danger of conflict of water is especially severe in the Middle East which is characterized by the low level of precipitation and high temperatures. The Middle Eastern countries have been involved in a constant state of political tension and the gap between the growing number of inhabitants and the fixed supply of water and land has been a factor in contributing to this tension. -

Hereof, Please Address Your Written Request to the New York University Annual Survey of American Law

\\server05\productn\n\nys\66-2\front662.txt unknown Seq: 1 12-OCT-10 15:54 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY ANNUAL SURVEY OF AMERICAN LAW VOLUME 66 ISSUE 2 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW ARTHUR T. VANDERBILT HALL Washington Square New York City \\server05\productn\n\nys\66-2\front662.txt unknown Seq: 2 12-OCT-10 15:54 New York University Annual Survey of American Law is in its sixty-ninth year of publication. L.C. Cat. Card No.: 46-30523 ISSN 0066-4413 All Rights Reserved New York University Annual Survey of American Law is published quarterly at 110 West 3rd Street, New York, New York 10012. Subscription price: $30.00 per year (plus $4.00 for foreign mailing). Single issues are available at $16.00 per issue (plus $1.00 for foreign mailing). For regular subscriptions or single issues, contact the Annual Survey editorial office. Back issues may be ordered directly from William S. Hein & Co., Inc., by mail (1285 Main St., Buffalo, NY 14209-1987), phone (800- 828-7571), fax (716-883-8100), or email ([email protected]). Back issues are also available in PDF format through HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org). All articles copyright 2010 by the New York University Annual Survey of American Law, except when otherwise expressly indicated. For permission to reprint an article or any portion thereof, please address your written request to the New York University Annual Survey of American Law. Copyright: Except as otherwise provided, the author of each article in this issue has granted permission for copies of that article to be made for classroom use, provided that: (1) copies are distributed to students at or below cost; (2) the author and journal are identified on each copy; and (3) proper notice of copyright is affixed to each copy. -

Iraqi Red Crescent Organization

Iraqi Red Crescent Organization The Internally Displaced People in Iraq Update 30 27 January 2008 For additional information, please contact: In Iraq: 1. Iraqi Red Crescent Organization, President- Dr. Said Hakki, email: [email protected] 2. Iraqi Red Crescent Organization, Vice President- Dr. Jamal Karboli, email: [email protected] 3. International Relation Department manager [email protected]; Mobile phone: +964 7901669159; Telephone: +964 1 5372925/24/23 4. Disaster Management Department manager [email protected]; Mobile phone: +964 7703045043; Telephone: +964 1 5372925/24/23 In Jordan: Amman Coordination Office: [email protected]; Mobile phone (manager):+962 796484058; Mobile phone (deputy manager): +962 797180940 Also, visit the Iraqi Red Crescent Organization web site: iraqiredcrescent.org The Internally Displaced People in Iraq; update 30; 27 January 2008 Table of contents BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................................... 2 REFUGEES IN IRAQ................................................................................................................................ 2 RETURNEES FROM SYRIA ...................................................................................................................... 3 THE TURKISH BOMBARDMENT IN THE NORTH OF IRAQ .......................................................................... 3 THE INTERNALLY DISPLACED PEOPLE (IDP)........................................................................................ -

Isis in the Southwest Baghdad Belts

ALI DAHLIN BACKGROUNDER NOVEMBER 24, 2014 ISIS IN THE SOUTHWEST BAGHDAD BELTS hroughout September and October 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) moved to Tconsolidate its control of terrain in al-Anbar province, closing the gap in its Euphrates control between Haditha and Ramadi. While ISIS does not yet control either city, ISIS seized the midway point between at Hit on October 2, 2014.1 This backgrounder will examine ISIS forces southwest of Baghdad, which have recently been the focus of a counter-offensive by the ISF. The expulsion of ISIS forces southwest of Baghdad may generate a strategic advantage for the ISF; but it may also initially heighten the threat to Baghdad. The southwestern Baghdad Belts have been an ISIS stronghold of this terrain to ISIS, it is necessary to estimate the remaining for some time. ISIS reestablished itself in 2013 within the strength of ISIS forces between south of Amiriyat al-Fallujah and historic “Triangle of Death” comprised of a cluster of cities 20 km northern Babil. It is unclear at this time whether ISIS attacks south of Baghdad, including Mahmudiyah, Latifiyah, and on Amiriyat al-Fallujah in April 2014 were purely defensive Yusifiyah. Shi’a militia groups have had control of these areas measures to protect Fallujah, or whether they were offensive since 2013, whereas ISIS has been present in the countryside, measures to consolidate territory in the northern “outer” ring. particularly in the Karaghuli tribal areas, including Jurf Closer examination of ISIS activities from January 2014 to al-Sakhar. ISIS presence in this area allowed the group to October 2014 reveal that there are separate ISIS sub- launch VBIED attacks in southwestern Baghdad in 2013, as well as to project influence over populated areas to the west in Anbar province.2 These towns, including Jurf al-Sakhar, Farisiyah, Fadhiliyah, Abu Ghraib, and Amiriyat al-Fallujah, link ISIS in northern Babil with ISIS in Anbar.