An Analysis of the Styles of C. Saint-Saëns and W. A. Mozart with Emphasis on Their Clarinet Compositions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Master of Music Recital in Clarinet

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2019 A master of music recital in clarinet Lucas Randall University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2019 Lucas Randall Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Randall, Lucas, "A master of music recital in clarinet" (2019). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 1005. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/1005 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MASTER OF MUSIC RECITAL IN CLARINET An Abstract of a Recital Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Lucas Randall University of Northern Iowa December, 2019 This Recital Abstract by: Lucas Randall Entitled: A Master of Music Recital in Clarinet has been approved as meeting the recital abstract requirement for the Degree of Master of Music. ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Amanda McCandless, Chair, Recital Committee ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Stephen Galyen, Recital Committee Member ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Ann Bradfield, Recital Committee Member ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Jennifer Waldron, Dean, Graduate College This Recital Performance by: Lucas Randall Entitled: A Master of Music Recital in Clarinet Date of Recital: November 22, 2019 has been approved as meeting the recital requirement for the Degree of Master of Music. -

A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’S Clarinet Sonata

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata Kenneth T. Aoki Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Composition Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation Aoki, Kenneth T., "A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata" (1968). All Master's Theses. 1077. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1077 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SONATA WITH AN ANALYSIS AND COMPARISON OF A BRAHMS' AND HINDEMITH'S CLARINET SONATA A Covering Paper Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Music Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Education by Kenneth T. Aoki August, 1968 :N01!83 i iuJ :JV133dS q g re. 'H/ £"Ille; arr THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC CENTRAL WASHINGTON STATE COLLEGE presents in KENNETH T. AOKI, Clarinet MRS. PATRICIA SMITH, Accompanist PROGRAM Sonata for Clarinet and Piano in B flat Major, Op. 120 No. 2. J. Brahms Allegro amabile Allegro appassionato Andante con moto II Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano .............................................. 8. Heiden Con moto Andante Vivace, ma non troppo Caprice for B flat Clarinet ................................................... -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

Swan Lake Takes out the Classic 100: Dance Countdown

10 JUNE 2018 – EMBARGOED UNTIL 19:01 AEST-- Swan Lake takes out the Classic 100: Dance Countdown Swan Lake has been named Australia’s favourite classical dance music in ABC Classic FM’s Classic 100 Countdown. Australia’s favourite classical music event has celebrated the brilliant diversity, vivid colour and irresistible impulse of dance, by counting down the music that makes its audiences move. Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, one of the world’s most beloved ballets, tells the story of Odette, a princess transformed into a swan by the curse of an evil sorcerer. Australia’s passionate community of music lovers voted in their thousands in the annual campaign by ABC Classic FM, our only national classical music station. Nearly 2000 works were reduced by public voting to the final 100 broadcast this weekend. More than 50% of the performers featured in this flagship event are Australian, exemplifying the ABC’s crucial role in nurturing local talent. ABC Classic FM is dedicated to investing in high-quality and distinctive Australian music and performance, free for all Australians. ABC Classic FM has collaborated with The Australian Ballet to produce three films specifically for the Countdown. Emerging choreographers Alice Topp, Richard House and Ella Havelka created striking new responses to the top three featured works: Swan Lake, The Nutcracker Suite, and Romeo and Juliet. Why Dance, a 3 x 20 minute feature series from the ABC’s Dr Ann Jones, has launched on air on ABC Classic FM, online and on the ABC listen app to mark this year’s theme. In association with The Australian Ballet, Sydney Dance Company and Bangarra Dance Theatre, Ann explores female choreographers in the male- dominated world of ballet, the importance of dance in Indigenous culture, and the healing role of dance in the lives of some everyday Australians. -

Scratch Pad 77 March 2011 TARAL WAYNE :: NIALL Mcgrath & TIM TRAIN :: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) :: BRUCE GILLESPIE :: ABC CLASSICS Top 100 Scratch Pad 77 March 2011

Scratch Pad 77 March 2011 TARAL WAYNE :: NIALL McGRATH & TIM TRAIN :: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) :: BRUCE GILLESPIE :: ABC CLASSICS Top 100 Scratch Pad 77 March 2011 Based on the non-mailing comments section of *brg* 67 and 68, a fanzine for ANZAPA (Australia and New Zealand Amateur Publishing Association) written and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard St, Greensborough VIC 3088. Phone: (03) 9435 7786. Email: [email protected]. Member fwa. Website: GillespieCochrane.com.au Contents 3 Unsolved mysteries of the hereafter — by Taral Wayne 6 The brand new Scratch Pad poetry spot — by Niall McGrath and Tim Train 9 Ditmar’s best and favourite films of 2010 — by Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) 15 Shining shores: Bruce Gillespie’s favourites 2010 — by Bruce Gillespie 36 ABC Classic 100 ten years on: 2010 — introduced by Bruce Gillespie Cover graphic — ‘Evening Phenomenon’ by Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Cartoon p. 3: ‘Unsolved mysteries’ — by Taral Wayne 2 Unsolved mysteries of the hereafter by Taral Wayne I think some scholar, or someone who wanted to be mistaken for one, claimed that the translation from the Koran was wrong, and it wasn’t ‘seventy virgins’, but something like ‘seventy figs’, that a good Muslim could expect in Paradise, and that it only meant the blessed would be in the midst of plenty. I’m not sure I buy that. It was only 1500 years ago, and I don’t think Arabic then was so different from modern Arabic that millions of Arab Muslims make such an elementary mistake. But who knows ... maybe Allah really only did mean that the nearly arrived would be greeted with a plate of figs .. -

May 2018 List

May 2018 Catalogue Issue 25 Prices valid until Wednesday 27 June 2018 unless stated otherwise 0115 982 7500 [email protected] Your Account Number: {MM:Account Number} {MM:Postcode} {MM:Address5} {MM:Address4} {MM:Address3} {MM:Address2} {MM:Address1} {MM:Name} 1 Welcome! Dear Customer, Glorious sunshine and summer temperatures prevail as this foreword is being written, but we suspect it will all be over by the time you are reading it! On the plus side, at least that means we might be able to tempt you into investing in a little more listening material before the outside weather arrives for real… We were pleasantly surprised by the number of new releases appearing late April and into May, as you may be able to tell by the slightly-longer-than-usual new release portion of this catalogue. Warner & Erato certainly have plenty to offer us, taking up a page and half of the ‘priorities’ with new recordings from Nigel Kennedy, Philippe Jaroussky, Emmanuel Pahud, David Aaron Carpenter and others, alongside some superbly compiled boxsets including a Massenet Opera Collection, performances from Joseph Keilberth (in the ICON series), and two interesting looking Debussy collections: ‘Centenary Discoveries’ and ‘His First Performers’. Rachel Podger revisits Vivaldi’s Four Seasons for Channel Classics (already garnering strong reviews), Hyperion offer us five new titles including Schubert from Marc-Andre Hamelin and Berlioz from Lawrence Power and Andrew Manze (see ‘Disc of the Month’ below), plus we have strong releases from Sandrine Piau (Alpha), the Belcea Quartet joined by Piotr Anderszewski (also Alpha), Magdalena Kozena (Supraphon), Osmo Vanska (BIS), Boris Giltberg (Naxos) and Paul McCreesh (Signum). -

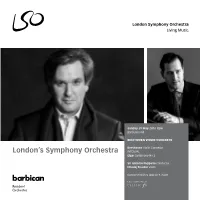

Nikolaj Znaider in 2016/17

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 29 May 2016 7pm Barbican Hall BEETHOVEN VIOLIN CONCERTO Beethoven Violin Concerto London’s Symphony Orchestra INTERVAL Elgar Symphony No 2 Sir Antonio Pappano conductor Nikolaj Znaider violin Concert finishes approx 9.20pm 2 Welcome 29 May 2016 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A very warm welcome to this evening’s LSO ELGAR UP CLOSE ON BBC iPLAYER concert at the Barbican. Tonight’s performance is the last in a number of programmes this season, During April and May, a series of four BBC Radio 3 both at the Barbican and LSO St Luke’s, which have Lunchtime Concerts at LSO St Luke’s was dedicated explored the music of Elgar, not only one of to Elgar’s moving chamber music for strings, with Britain’s greatest composers, but also a former performances by violinist Jennifer Pike, the LSO Principal Conductor of the Orchestra. String Ensemble directed by Roman Simovic, and the Elias String Quartet. All four concerts are now We are delighted to be joined once more by available to listen back to on BBC iPlayer Radio. Sir Antonio Pappano and Nikolaj Znaider, who toured with the LSO earlier this week to Eastern Europe. bbc.co.uk/radio3 Following his appearance as conductor back in lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts November, it is a great pleasure to be joined by Nikolaj Znaider as soloist, playing the Beethoven Violin Concerto. We also greatly look forward to 2016/17 SEASON ON SALE NOW Sir Antonio Pappano’s reading of Elgar’s Second Symphony, following his memorable performance Next season Gianandrea Noseda gives his first concerts of Symphony No 1 with the LSO in 2012. -

02 October 2020

02 October 2020 12:01 AM Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) Early one morning for voice and piano Elizabeth Watts (soprano), Paul Turner (piano) GBBBC 12:05 AM Juan Crisostomo Arriaga (1806-1826) Los Esclavos Felices - overture Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, Juanjo Mena (conductor) NONRK 12:12 AM Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Variations on "Deandl is arb auf mi'" for string trio Leopold String Trio GBBBC 12:19 AM Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Double Concerto in C minor, BWV 1060 Hans-Peter Westermann (oboe), Mary Utiger (violin), Camerata Koln DEWDR 12:33 AM Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Fugue (BWV.542) 'Great' (orig. for organ) Guitar Trek AUABC 12:40 AM Isaac Albeniz (1860-1909) Suite espanola , Op 47 Ilze Graubina (piano) LVLR 01:02 AM Eugen Suchon (1908-1993) The Night of the Witches, symphonic poem Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, Mario Kosik (conductor) SKSR 01:22 AM Camille Saint-Saens (1835-1921) Clarinet Sonata in E flat, Op 167 Annelien Van Wauwe (clarinet), Simon Lepper (piano) GBBBC 01:39 AM Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Nisi Dominus (Psalm 127) for voice and orchestra (RV.608) Matthew White (counter tenor), Arte dei Suonatori, Eduardo Lopez Banzo (conductor) PLPR 02:01 AM Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936),Anatoly Lyadov (1855-1914),Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840- 1893) Fugue in D minor; Sarabande in D minor; Polka in D; Excerpts from 'The Seasons' Maria Wloszczowska (violin), Joseph Puglia (violin), Timothy Ridout (viola), Xenia Jankovic (cello), Alasdair Beatson (piano) CHSRF 02:26 AM Igor Stravinsky (1882 - 1971) Divertimento -

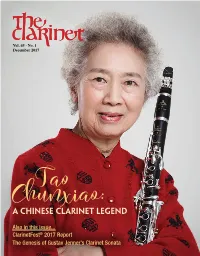

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

School of Music 2016–2017

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Music 2016–2017 School of Music 2016–2017 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Goff-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 3rd Floor, 203.432.0849. -

Mrs. James R. Preston Memorial Chamber Music Series: Evening of Diamonds I Mr

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Mrs. James R. Preston Memorial Chamber Music Series: Evening of Diamonds I Mr. Kenneth Graves, Clarinet assisted by Ms. Shellie Brown, Violin & Dr. Stephen Sachs, Piano Saturday, October 13, 2012 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the evening program. Please come and greet the performers. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert. Please turn off all pagers and cell phones. PROGRAM Sonata for Clarinet and Piano Francis Poulenc • 1899 - 1963 I. Allegro tristamente II. Romanza III. Allegro con fuoco Nocturne Para Clarinette et Piano, Op. 26 Jacques Hétu • 1938 - 2010 Mr. Kenneth Graves, Clarinet; Dr. Stephen Sachs, Piano Trio for Clarinet, Violin, and Piano Aram Khachaturian • 1903 - 1978 I. Andante II. Allegro III. Moderato Ms. Shellie Brown, Violin; Mr. Kenneth Graves, Clarinet; Dr. Stephen Sachs, Piano INTERMISSION Ingenuidad Para Clarinet y Piano, Op. 8/59 Miguel Yuste • 1870 - 1947 Vier Stücke für Klarinette und Klavier, Op. 5 Alban Berg • 1885 - 1935 I. Mässig II. Sehr langsam III. Sehr rasch IV. Langsam Preludes for Piano George Gershwin • 1898 - 1937 I. Allegro ben rimato e deciso II. Andante con moto e poco rubato III. Allegro ben rimato e deciso Mr. Kenneth Graves, Clarinet; Dr. Stephen Sachs, Piano PROGRAM NOTES Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (1962) German sonata form, Poulenc’s piece takes The Sonata for Clarinet and Piano was among inspiration from the less rigid 18th-century French Poulenc’s final works and, like his Oboe Sonata, it sonatas of Couperin and Rameau.