Note to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health and Physical Education

Resource Guide Health and Physical Education The information and resources contained in this guide provide a platform for teachers and educators to consider how to effectively embed important ideas around reconciliation, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and contributions, within the specific subject/learning area of Health and Physical Education. Please note that this guide is neither prescriptive nor exhaustive, and that users are encouraged to consult with their local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, and critically evaluate resources, in engaging with the material contained in the guide. Page 2: Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 3: Timeline of Key Dates in the more Contemporary History of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 5: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Organisations, Programs and Campaigns Page 6: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Sportspeople Page 8: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Events/Celebrations Page 12: Other Online Guides/Reference Materials Page 14: Reflective Questions for Health and Physical Education Staff and Students Please be aware this guide may contain references to names and works of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that are now deceased. External links may also include names and images of those who are now deceased. Page | 1 Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education “[Health and] healing goes beyond treating…disease. It is about working towards reclaiming a sense of balance and harmony in the physical, psychological, social, cultural and spiritual works of our people, and practicing our profession in a manner that upholds these multiple dimension of Indigenous health” –Professor Helen Milroy, Aboriginal Child Psychiatrist and Australia’s first Aboriginal medical Doctor. -

Australia and the Pacific

AUSTRALIA AND THE PACIFIC: THE AMBIVALENT PLACE OF PACIFIC PEOPLES WITHIN CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIA Scott William Mackay, BA (Hons), BSc July 2018 Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Australian Indigenous Studies Program School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne 0000-0002-5889 – Abstract – My thesis examines the places (real and symbolic) accorded to Pacific peoples within the historical production of an Australian nation and in the imaginary of Australian nationalism. It demonstrates how these places reflect and inform the ways in which Australia engages with the Pacific region, and the extent to which Australia considers itself a part of or apart from the Pacific. While acknowledging the important historical and contemporary differences between the New Zealand and Australian contexts, I deploy theoretical concepts and methods developed within the established field of New Zealand- centred Pacific Studies to identify and analyse what is occurring in the much less studied Australian-Pacific context. In contrast to official Australian discourse, the experiences of Pacific people in Australia are differentiated from those of other migrant communities because of: first, Australia’s colonial and neo-colonial histories of control over Pacific land and people; and second, Pacific peoples' important and unique kinships with Aboriginal Australians. Crucially the thesis emphasises the significant diversity (both cultural and national) of the Pacific experience in Australia. My argument is advanced first by a historicisation of Australia’s formal engagements with Pacific people, detailing intersecting narratives of their migration to Australia and Australia’s colonial and neo- colonial engagements within the Pacific region. -

Heritage Interpretation Strategy for Western Sydney Stadium

Heritage Interpretation Strategy for Western Sydney Stadium Prepared by Betteridge Consulting Pty Ltd for Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd Archaeology and Heritage Consultants and Lendlease FINAL 8 April 2019 Betteridge Consulting Pty Ltd (ABN 15 602 062 297) 42 BOTANY STREET RANDWICK NSW 2031 Email: [email protected] Web: www.musecape.com.au Mobile (Margaret Betteridge): +61 (0)419 238 996 Mobile (Chris Betteridge): +61 (0)419 011 347 SPECIALISTS IN THE IDENTIFICATION, ASSESSMENT, MANAGEMENT AND INTERPRETATION OF CULTURAL HERITAGE WESTERN SYDNEY STADIUM INTERPRETATION STRATEGY prepared by Betteridge Consulting Pty Ltd Final 6 March 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 6 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................... 8 1.2 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 9 1.3 Consultation .............................................................................................................. 9 1.3.1 Consultation with Registered Aboriginal Parties ....................................... 10 1.3.2 Consultation with the Heritage Division, Office of the Environment and Heritage .................................................................................................................... -

Foundation Licensed Under Cover Driving Range Bar • Functions

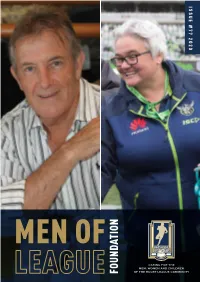

ISSUE #77 2020 MEN OF CARING FOR THE MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN OF THE RUGBY LEAGUE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION LICENSED UNDER COVER DRIVING RANGE BAR • FUNCTIONS Aces Sporting Club • Springvale Rd & Hutton Rd, Keysborough Ph. 9701 5000 • acessportingclub.com.au • /AcesSportingClub LOOK FORWARD TO REOPENING SOON ✃ PRPREESENTSENT THISTHIS FFLLYEYERR ININ THE THE DRIVING DRIVING RANGE RANGE FOR FOR 200200 BBAALLLLSS FFOORR $$1100 SPOSPORRTTIINGNG CCLULUBB Can not be used in conjunction with any other offer. Terms and Conditions Apply. IN THIS FROM THE OUR COVER Introducing our newest board member Katrina Fanning and recently announced life member Tony Durkin. PROFESSOR THE INSIDE THIS ISSUE 5 McCloy Group corporate membership HONOURABLE 6 Tony Durkin 8 Lionel Morgan STEPHEN MARTIN 11 Katrina Fanning 14 Socially connecting As you read this message, the Foundation brings enormous experience to our board 16 Try July is still unfortunately greatly impacted by as a former Jillaroo, having played 26 Tests 17 Arthur Summons COVID-19 and the necessary restrictions that for Australia and held the roles of president 18 Keith Gee have been imposed by health and government of the Australian Women’s Rugby League 21 Mortimer Wines promotion authorities. Association, chairperson of the Australian 22 Noel Kelly Rugby League Indigenous Council and a 24 Champion Broncos 20 years on The Foundation itself remains in hibernation director of the board of the Canberra Raiders. 26 Ranji Joass mode. Most staff remain stood down, and Welcome Katrina! 34 Phillippa Wade and her Storm Sons we are fortunate that JobKeeper has been 28 Q/A with Peter Mortimer available to us. -

Sir Peter Leitch Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 21st June 2017 Newsletter #175 Wasn’t He Supposed to Sign For Us? By David Kemeys Former Sunday Star-Times Editor, Former Editor-in-Chief Suburban Newspapers, Long Suffering Warriors Fan O MUCH for the speculation about Te Maire Martin coming in to replace Kieran Foran. SFor those of you living in a cave, and who haven’t heard, instead the Kiwis international has signed on the dotted line for the Cowboys. Cowboys or Warriors - not much of a choice is it? He has signed a deal with the Cowboys until the end of 2019, and considering most of would be willing to predict he will jot oust Johnathan or Matt Moylan from the halves, you’d have to wonder what the attraction of Townsville is compared to Mt Smart. Scratch that, you would not have to wonder really would you? Title prospect or perennial under-achiever? Martin was wanted at the Cowboys two years ago, but chose the Panthers, apparently because he wanted to “fast-track” his career. How’d that work out for you mate? Still just 21, Martin has plenty to learn, but I am with those who said he had plenty to offer too, and I am gutted he has turned his back on us. To be fair, who can blame the young man when he has the chance to learn from Thurston, who is the best there is. He said it himself: “I'll just soak in as much as I can from JT and try and work on my game. -

State of Origin Records

STATE OF ORIGIN RECORDS 1980 Lang Park, July 8 Qld: Colin Scott; Kerry Boustead, Mal Meninga, Chris Close, Brad Backer; Alan Smith, Greg Oliphant; Wally Lewis, Rod Reddy, Rohan Hancock, Arthur Beetson (c), John Lang, Rod Morris. Replacements: Norm Carr (not used), Bruce Astill (not used). Coach: John McDonald. NSW: Graham Eadie; Chris Anderson, Steve Rogers, Mick Cronin, Greg Brentnall; Alan Thompson, Tom Raudonikis (c); Jim Leis, Graeme Wynn, Bob Cooper, Craig Young, Steve Edge, Gary Hambly. Replacements: Robert Stone, Steve Martin (not used). Coach: Ted Glossop. Queensland 20 (Boustead, Close tries; Meninga 7 goals) d. New South Wales 10 (Raudonikis, Brentnall tries; Cronin 2 goals). Crowd: 33,210. Referee: Billy Thompson (Great Britain). Man of the Match: Chris Close. 1981 Lang Park, July 28 Qld: Colin Scott; Brad Backer, Mal Meninga, Chris Close, Mitch Brennan; Wally Lewis (c), Ross Henrick; Chris Phelan, Paul McCabe, Rohan Hancock, Rod Morris, Greg Conescu, Paul Khan. Replacements: Norm Carr, Mark Murray. Coach: Arthur Beetson. NSW: Phil Sigsworth; Terry Fahey, Mick Cronin, Steve Rogers (c), Eric Grothe; Terry Lamb, Peter Sterling; Ray Price, Les Boyd, Peter Tunks, Ron Hilditch, Barry Jensen, Steve Bowden. Replacements: Garry Dowling, Graham O’Grady (not used). Coach: Ted Glossop. Queensland 22 (Backer, Close, Lewis, Meninga (penalty) tries; Meninga 5 goals) d. New South Wales 15 (Grothe 2, Cronin tries; Cronin 3 goals). Crowd: 25,613. Referee: Kevin Steele (New Zealand). Man of the Match: Chris Close. 1982 Game 1: Lang Park, June 1 NSW: Greg Brentnall; Chris Anderson, Ziggy Niszczot, Mick Cronin, Steve Rogers; Alan Thompson, Steve Mortimer; Ray Price, John Muggleton, Tony Rampling, Craig Young, Max Krilich (c), John Coveney. -

Tales from Coathanger City – Ten Years of Tom Brock Lectures Contents

Tales from Coathanger City A dapper Tom Brock, aged 37, at Redfern Oval Ten Years of Tom Brock Lectures Edited by Richard Cashman University of Technology, Sydney Tales from Coathanger City Ten Years of Tom Brock Lectures Edited by Richard Cashman University of Technology, Sydney Published by the Australian Society for Sports History and the Tom Brock Bequest Committee Published by the Australian Society for Sports History and the Tom Brock Bequest Committee Sydney, 2010 © Tom Brock Bequest Committee and individual authors This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission of the publisher. Images provided by Ian Heads, Terry Williams and individual authors. ISBN: 978-0-7334-2899-9 Design and layout: UNSW Design Studio Printer: Graphitype Front cover illustration: Grapple tackles have long been part of rugby league. Newtown player Dick Townsend is tackling (or grappling) Wests’ centre Peter Burns in the 1918 City Cup Final, which was won by Western Suburbs (Terry Williams). -ii- Tales from Coathanger City – Ten Years of Tom Brock Lectures Contents Thomas George Brock (1929–97) 1 The Tom Brock Bequest 4 Whither the Squirrel Grip? 6 A Decade of Lectures on the ‘Greatest Game of All’ Andrew Moore Tom Brock lectures 1999 to 2008 1 Jimmy Devereux’s Yorkshire Pudding: Reflections on the 21 Origins of Rugby League in New South Wales and Queensland Andrew Moore (1999) 2 Gang-gangs at One O’Clock … and Other Flights of Fancy: 45 A Personal Journey through Rugby League Ian Heads OAM (2000) 3 Sydney: Heart of Rugby League 61 Alex Buzo (2001) 4. -

'From a Federation Game to a League of Nations'

10TH ANNUAL TOM BROCK LECTURE BOWLER’S CLUB Sydney • 6 november 2008 ‘From a Federation Game to a League of Nations’ Mr Lex Marinos OAM Published in 2009 by the Tom Brock Bequest Committee on behalf of the Australian Society for Sports History © ASSH and the Tom Brock Bequest Committee This monograph is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-7334-2706-0 Illustrations provided by Terry Williams and Lex Marinos. Thanks are due to the respective owners of copyright for permission to publish these images. Design & layout: UNSW Design Studio Printer: Graphitype TOM BROCK BEQUEST The Tom Brock Bequest, given to the Australian Society for Sports History (ASSH) in 1997, consists of the Tom Brock Collection supported by an ongoing bequest. The Collection, housed at the State Library of New South Wales, includes manuscript material, newspaper clippings, books, photographs and videos on rugby league in particular and Australian sport in general. It represents the finest collection of rugby league material in Australia. ASSH has appointed a Committee to oversee the Bequest and to organise appropriate activities to support the Collection from its ongoing funds. Objectives: 1. To maintain the Tom Brock Collection. 2. To organise an annual scholarly lecture on the history of Australian rugby league. 3. To award an annual Tom Brock Scholarship to the value of $5,000. 4. To undertake any other activities which may advance the serious study of rugby league.