Evolutionary Psychology I: the Science of Human Nature Allen D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Origins

HUMAN ORIGINS Methodology and History in Anthropology Series Editors: David Parkin, Fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford David Gellner, Fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford Volume 1 Volume 17 Marcel Mauss: A Centenary Tribute Learning Religion: Anthropological Approaches Edited by Wendy James and N.J. Allen Edited by David Berliner and Ramon Sarró Volume 2 Volume 18 Franz Baerman Steiner: Selected Writings Ways of Knowing: New Approaches in the Anthropology of Volume I: Taboo, Truth and Religion. Knowledge and Learning Franz B. Steiner Edited by Mark Harris Edited by Jeremy Adler and Richard Fardon Volume 19 Volume 3 Difficult Folk? A Political History of Social Anthropology Franz Baerman Steiner. Selected Writings By David Mills Volume II: Orientpolitik, Value, and Civilisation. Volume 20 Franz B. Steiner Human Nature as Capacity: Transcending Discourse and Edited by Jeremy Adler and Richard Fardon Classification Volume 4 Edited by Nigel Rapport The Problem of Context Volume 21 Edited by Roy Dilley The Life of Property: House, Family and Inheritance in Volume 5 Béarn, South-West France Religion in English Everyday Life By Timothy Jenkins By Timothy Jenkins Volume 22 Volume 6 Out of the Study and Into the Field: Ethnographic Theory Hunting the Gatherers: Ethnographic Collectors, Agents and Practice in French Anthropology and Agency in Melanesia, 1870s–1930s Edited by Robert Parkin and Anna de Sales Edited by Michael O’Hanlon and Robert L. Welsh Volume 23 Volume 7 The Scope of Anthropology: Maurice Godelier’s Work in Anthropologists in a Wider World: Essays on Field Context Research Edited by Laurent Dousset and Serge Tcherkézoff Edited by Paul Dresch, Wendy James, and David Parkin Volume 24 Volume 8 Anyone: The Cosmopolitan Subject of Anthropology Categories and Classifications: Maussian Reflections on By Nigel Rapport the Social Volume 25 By N.J. -

Human Social Behavioral Systems:Ethological

Human Ethology Bulletin 29 (2014)1: 39-65 Teoretical Reviews HUMAN SOCIAL BEHAVIORL SYSTEMS: ETHOLOGICAL FRMEWORK FOR A UNIFIED THEORY Liane J. Leedom University of Bridgeport, Psychology Department, CT, US [email protected] ABSTRCT Drive theories of motivation proposed by Lorenz and Tinbergen did not survive experimental scrutiny; however these were replaced by the behavioral systems famework. Unfortunately, political forces within science including the rise of sociobiology and comparative psychology, caused neglect of this important famework. Tis review revives the concept of behavioral systems and demonstrates its utility in the development of a unifed theory of human social behavior and social bonding. Although the term “atachment” has been used to indicate social bonds which motivate afliation, four diferentiable social reward systems mediate social proximity and bond formation: the afliation (atachment), caregiving, dominance and sexual behavioral systems. Ethology is dedicated to integrating inborn capacities with experiential learning as well as the proximal and ultimate causes of behavior. Hence, the behavioral systems famework developed by ethologists nearly 50 years ago, enables discussion of a unifed theory of human social behavior. Key words: atachment, caregiving, dominance, sex, behavioral systems _________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Te last 50 years has seen the waning of ethology in the United States, accompanied by the growth of sociobiology, comparative psychology and evolutionary psychology (Barlow, 1989; Burkhardt, 2005; Greenberg, 2010). Sociobiologists, in particular, proclaimed the death of ethology and promised their nascent discipline and genetic mechanisms would provide an understanding of human social behavior (Barlow, 1989; E. O. Wilson, 2000). It has been 13 years since the sequencing of the human genome (Venter et al., 2001), sociobiology has fallen into “disarray” (D. -

Human Ethology Bulletin

Human Ethology Bulletin VOLUME 19, ISSUE 4 ISSN 0739‐2036 December 2004 © 2004 The International Society for Human Ethology ISHE website: http://evolution.anthro.univie.ac.at/ishe.html The 17th Biennial ISHE Conference was held in Ghent, Belgium from July 27‐30. Report on ISHE 2004 The program was published in the June 2004 issue, and the Minutes of the General by Kris Thienpont Assembly appeared in the previous issue. This issue includes additional photographs Ghent is a city with many faces. One of the from the meeting, as well as a report on the better known sides is its annual week of meeting authored by conference host (and exuberant festivities at the end of July, with recently appointed Associate Book Review hundreds of concerts, performances, street Editor), Kris Theinpont. Also in this issue is art exhibits, thousands of people in and a revised version of the tribute to Linda around the city center, and the odd Mealey that Andy Thomson delivered in scientific society that considers that Ghent. particular week as a good occasion for organizing a conference. Additional information on the conference, including photographs and abstracts of ISHE participants arriving in Ghent on papers, can be found at: th Monday 26 were met with the state of www.psw.ugent.be/bevolk/ishe2004 pleasant chaos that accompanies the Ghent Festivities and could enjoy the last day and night of this annual bacchanaal. Fortunately, our meeting began the day after, when the dust had settled, the streets had been cleaned, and the public transport system had gone on strike. -

Syllabus a History of Animals in the Atlantic World

Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, El Primer Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno, ed. Rolena Adorno (Copenhagen: Royal Library Digital Facsimile, 2002), 1105. Special topics: A history of animals in the atlantic world History 497, section 001 Abel Alves Spring Semester 2011 Burkhardt Building 216 Monday, 6:30-9:10 PM [email protected]; 285-8729 Burkhardt Building 106 Office Hours: Monday, 5:00-6:30; also by appointment Prospectus The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss once wrote that animals are not only “good to eat,” they are “good to think.” Throughout the course of human history, people have interacted with other animals, not only using them for food, clothing, labor and entertainment, but also associating with them as pets and companions, and even appreciating their behaviors intrinsically. Nonhuman animals have been our symbols and models, and they have even channeled the sacred for us. This course will explore the interaction of humans with other animals in the context of the Atlantic World from prehistoric times to the present. Our case studies will include an exploration of our early hominid heritage as prey as well as predators; our domestication of other animals to fit our cultural needs; how nonhuman animals were used and sometimes respected in early agrarian empires like those of Rome and the Aztecs; how Native American, African and Christian religious traditions have wrestled with the concept of the “animal”; the impact of the Enlightenment and Darwinian thought; and the contemporary mechanization of life and call for animal rights. Throughout the semester, we will be giving other animals “voice,” even as Aristotle in The Politics said they possessed the ability to communicate. -

Hutnan Ethology Bulletin

Hutnan Ethology Bulletin http://evolution.anthro.univie.ac.at/ishe.html VOLUME 16, ISSUE 1 ISSN 0739-2036 MARCH 2001 © 1999 The International Society for Human Ethology extensively on the topic of human and animal aggression, including intergroup competition in primates and preindustrial, sexual violence, theories of war causation, and ethnocentrism. From 1990 to 2000 he was secretary of the EuropoenSociobiological Society and editor of its newsletter, and he is currently Vice-President and President-Elect of ISHE. In 1995 he published The Origin of War: The Evolution of a Male-Coalitional ReprOductive Strategy, a two volume work spanning a twenty year period of research. PL: lohan, let's begin with some background m your early years, yourtraining and the ideas and people that influenced you in your own development. Can yougive ussomebackground? JVDD: I was born in Eindhoven, in the south of the Netherlands. As a youth I never had the aspiration to be a scientist; I wanted to be a writer or an artist. I enjoyed (or suffered?) a classic education (a school type we call, oddly enough, a gymnasium) and then I had the opportunity to study in Groningen but I didn't knowwhat to do with my studies. On War and Peace PL: What year did youcometo Groningen? An Interview of JVDD: I carne in 1964. It was a very small town and you could just walk into lectures. I did Johan van der Dennen psychology, philosophy, sociology and medicine for a couple of years, and then ethology and by Peter LaFreniere biology; justsampling. It took someyears before I found my niche and then I had the opportunity to become a student assistant at the Polemological lohan van der Dennenwas bomin Eindhoven, The Institute (or 'Peace Research' Institute as it is Netherlands, in 1944 and studied behavioral knowninEnglish) of the University of Groningen, sciences at the University of Groningen. -

Human Ethology Bulletin, 18 (3), 2003 1

Human Ethology Bulletin, 18 (3), 2003 1 Human Ethology Bulletin http://evolution.anthro.univie.ac.at/ishe.html VOLUME 18, ISSUE 3 ISSN 0739-2036 SEPTEMBER 2003 © 2003 The International Society for Human Ethology ISHE to meet in Ghent, Belgium th th July 27 - 30 2004 The 17th Biennial Conference of the The views this town has to offer. Not far from the International Society for Human Ethology will be Graslei arises the Castle of the Counts, once the held in Ghent, Belgium next summer from the 27th medieval fortress of the Count of Flanders. Ghent to 30th of July. The Program Committee is busy can be discovered by boat, carriage, bicycle or on with advance preparations and will soon list foot. plenary speakers and issue a Call for Papers. The official language in Ghent is Dutch but most Ghent is one of Western Europe’s most attractive people also speak French, English and/or historical cities, known for its excellent gourmet German. The Belgian currency unit is the euro. dining and extensive cultural life. Its university There are exchange offices and banks in the city was founded in 1817 and is one of the largest centre, credit cards are accepted in most places. universities in the Low Countries. The city is located 55 km to the west of Brussels, covers 156 Transport sq. km of which 36 sq. km is port area. It is the second largest city of the region 'Flanders', and International air travellers usually arrive at the third centre in Belgium. Ghent is the core city Brussels International Airport. -

Course Unit Information Sheet (Syllabus) 2018/2019 1

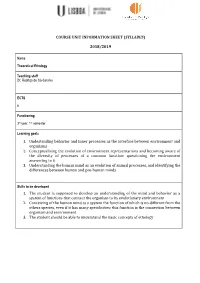

COURSE UNIT INFORMATION SHEET (SYLLABUS) 2018/2019 Name Theoretical Ethology Teaching staff Dr. Rodrigo de Sá-Saraiva ECTS 6 Functioning 3rd year, 1st semester Learning goals 1. Undestanding behavior and inner processes as the interface between environment and organisms 2. Conceptualizing the evolution of environment representarions and becoming aware of the diversity of processes of a common function: questioning the environment answering to it 3. Understanding the human mind as an evolution of animal processes, and identifying the differences between human and pre-human minds Skills to be developed 1. The student is supposed to develop an understanding of the mind and behavior as a system of functions that connect the organism to its evolutionary environment 2. Conceiving of the human mind as a system the function of which is no different from the others species, even if it has many specificities; this function is the connection between organism and environment 3. The student should be able to understand the basic concepts of ethology Prerequisites (precedences) * The are none Contents 1. What is ethology: genesis and object 2. The function cycle and behavioural systems 3. Monitoring and adapting to a variable but expectable environment 4. Protozoans: trial and error of a single response 5. Invertebrates : internal maps, releasers and searching images 6. Vertebrates: the evolution of mental maps 7. Primates, equipotentiality, theory of mind 8. Fossil Homo and the evolution the meta-conscience; episodic memory, control functions, inhibitory responses, connection between different representations and the evolution of language 9. Social systems, diversity and its causes. 10. Ethology, culture and psychology: is Homo sapiens an eusocial species? Bibliography Alcock, J., 2013: Animal Behavior: an evolutionary approach, 10th Ed. -

Human Sexual Behavior:Where We've Been and Where We're Going

Human Ethology Bulletin 29 (2014)1: 66-69 Book Review HUMAN SEXUAL BEHAVIOR: WHERE WE’VE BEEN AND WHERE WE’RE GOING Lora E. Adair Kansas State University, Department of Psychological Sciences, US [email protected] A Review of the Book Evolution and Human Sexual Behavior, Peter Gray and Justin Garcia. 2013. Harvard University Press, Cambridge. 354 pages. ISBN: 978-0674072732 (Hardback, $39.95). _________________________________________________________ “It is absurd to talk of one animal being higher than another” – C. R. Darwin (1837) With the help of evolutionary theory and comparative methods to explicate paterns in sexual behavior that run deeper than species distinctions, Peter Gray and Justin Garcia explore human sexuality throughout the lifespan in their recent book, Evolution and Human Sexual Behavior. Tis work provides a fresh perspective on human sexuality and sexual behaviors, placing human animals within a larger historical context, and gives readers the opportunity to perceive human sexuality as malleable, a product of thousands of years of change. Viewing sexual behaviors through an evolutionary lens, Gray and Garcia (2013) explore the relative costs and benefts associated with a particular aspect of an organism’s sexual behaviors, therein relating sexual behaviors to Hamilton’s rule (Hamilton, 1963). Tat is, to be favored by the forces of natural and sexual selection, a particular behavior or cognitive process must provide more benefts than costs to the organism in the domains of survival and reproduction. For example, a cognitive process that improves an organism’s ability to locate genetically compatible mates $ individuals with more dissimilar genes tend to produce fter ofspring (Gray & Garcia, 2013) $ without too high of a cost for that organism in terms of mate search time or cognitive efort. -

1995 – Volume 10 Issue 2

Human Ethology Bulletin Editor: Glenn Weisfeld Department of Psychology, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI 48202 USA 1-313-577-2835 (office) 577-8596 (lab), 577-2801 (messages), 577-7636 (Fax), 393-2403 (home) VOLUME 10, ISSUE 2 ISSN 0739-2036 JUNE 1995 © 1995 The International Society for Human Ethology SOCIETY NEWS membership form. Events: Here we provide information on ISHE World-Wide-Web Server Is upcoming and past conferences. If you wish to have something posted, you will have to e- On-Line mail it to us. Full information on ISHE conferences will, of course, be provided, By Karl Grammer, ISHE Secretary including abstracts of past meetings. I began this ISHE electronic bulletin Electronic Publications: This is my personal board in March as a sl,lpplement to the Bulletin. experimental page. There is also a link to In the test phase which lasted a week, the Psycholoquy, the first electronic scientific server had more than 300 visitors. journal. My idea is to publish posters (which have been prepared in electronic form) as The server can be reached under this pictures, and also figures to accompany journal URL: hUp:llevolution.humb.unvie.ac.at. For articles, such as videoclips, 3-D graphs, color access you need a direct Internet connection and pictures, and sounds. These things have been one of the following programs: Mosaic or difficult or impossible to publish previously. Netscape; both come in versions for either If there is enough interest, we will provide an Windows, MacOs or Unix. You can get both electronic journal for behavioural analysis. programs for free on the net. -

The Evolution of Human Ultra-Sociality

The Evolution of Human Ultra-sociality Peter J. Richerson Division of Environmental Studies University of California, Davis Davis, California 95616 [email protected] Robert Boyd Department of Anthropology University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, California 90024 [email protected] Version 2.01 June, 1997. In press: I. Eibl-Eibisfeldt and F. Salter, eds. Ideology, Warfare, and Indoctrinability. Please do not cite without authors’ permission. 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Human sociality in comparative perspective E.O. Wilson (1975) described humans as one of the four pinnacles of social evolution. The other pinnacles are the colonial invertebrates, the social insects, and the non-human mammals. Wilson separated human sociality from that of the rest of the mammals because, with the exception of the social insect like Naked Mole Rats, only humans have generated societies of a grade of complexity that approaches that of the social insects and colonial invertebrates. In the last few millennia, human societies have even begun to exceed, in numbers of individuals and degree of complexity, the societies of ants, termites, and corals. Human social complexity is based on quite different principles than the ultra-sociality of any other species. In all other known cases, the constituent individuals of societies are either genetically identical, as in the colonial invertebrates, or closely related, as in the social insects and non-human mammals. In the prototypical social insect colony, elaborate societies are built around a single reproductive queen, who suppresses the reproduction of workers in the colony. The offspring of the queen are siblings that share many genes in common, and they make up the work force of the colony. -

International Society for Human Ethology

Human ethology';1fI Editor: Robert M. Adams Department of Psychology. Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, KY 40475 USA (606) 622-1105, 622-1106 VOLUME 4, ISSUE 11 ISSN 0739-2036 SEPTEMBER. 1986 Published by the International Society for Human Ethology warm and never threatened to dampen extracurricular Officers of the Society activities such as the trip to the Andechs monastary or the dining and revelries at the Seewiesen Institute._ President This brief report would not be complete without a note on /rell/ius Lihl-l:.ihes/ddt the unbusiness meeting which followed the conference at Ma.\-Plallck-lmliIUl. f)-XIJI President Eibl-Eibesfeldt's cabin in the Austrian Tyrol. II SI'I'II·ie.H'II. /11'1'.\"1 (ierll/allr was there that two new officers were added: Bill Charlsworth as Society Dishwasher, and Wulf Secretary as Society Auto Mechanic. (iail lil'ill Following, you will find Barbara Hold-Cavell's opening kl/l'J"SOIl Ml'diclll remarks to the conference. The historical context she Phillldelphia. PA. l'."lA provides will be of particular interest to new ISHE members. Gail Zivin has provided minutes of the business Treasurer meeting. Of special note here in add ition to the Constitution Ill'rmall LJiel1.lhi' issue, are plans for U.S. meetings in [987 in New Mexico Primllle CI'IIIN and Massachusetts, and a 1989 meeting in Scotland. Rijsllrjk. Ni'lhl'rlalldl Membership Chair Call for Jar Fl'iermlill I "i.lf(/ Sllndili l/u.I/liwl Vice Presidential Nominees A Ihlll.(lIl'rqlll'. N M. ["SA Nominall.OnS, in self nominations Y,'(ce :R.re,sjgent of fQr H'Urna-n Etl'H;>I ogj!! T1}e names QfoprospecJive.candidates Report from the Conference of the se'hf, accompanied b' a 'one paragraph biographical statement by December I, 1986, to: International Society for Human Ethology Jay Feierman, M,D. -

Of the Books They Review. As Such, They Are Subjective Evaluations and Do

REVIEWS EDITED BY WILLIAM E. SOUTHERN Thefollowing reviews express the opinions of theindividual reviewers regarding the strengths, weaknesses, and value of thebooks they review. As such, they are subjective evaluations and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of theeditors or any officalpolicy of the A.O.U. Eds. The Shelduck: A study in behavioural ecology.-- for explaining many of the variablesin behavior and, I. J. Patterson. 1982. Cambridge, Cambridge Univer- indeed, is the main theme related to population lim- sity Press.x + 276 pp., 10 black-and-white drawings, itation that recursin discussionsthroughout the book. 101 figures, 68 tables. $49.50.--Traditionally, ethol- While this certainly seemsa proper emphasis,the ogistshave emphasizedstudies of causation,ontog- lack of precisedata on body weight in terms of pro- eny, evolution, and physiologicalbases of behavior, tein and lipids and the confounding variablesrelated often without concern for ecologicalvariables (e.g. to whole body weights (e.g. trap bias, gut contents, food supply) or relationships to population density. and prolonged breeding season so that individuals Similarly, population ecologists have emphasized are at different stagesof the reproductivecycle) re- numerical values in relation to ecological variables suit in a large amount of logical speculationand con- without data on variability of individuals or social clusionswithout critical data. Strengthsof the treat- behavior. Recent attempts to integrate ethology, ment are data on birds of known age and data on ecology,and population biology with the theory of food supply and use. Chapter 2 concludeswith a natural selectionhave produced a new field that is rather lengthy treatment of world distribution of now commonly termed Behavioral Ecology (e.g.J.R.