Comments on the Design for the Environment (Dfe) Program Alternatives Assessment Criteria for Hazard Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Assessment Report on Microplastics

An Assessment Report on Microplastics This document was prepared by B Stevens, North Carolina Coastal Federation Table of Contents What are Microplastics? 2 Where Do Microplastics Come From? 3 Primary Sources 3 Secondary Sources 5 What are the Consequences of Microplastics? 7 Marine Ecosystem Health 7 Water Quality 8 Human Health 8 What Policies/Practices are in Place to Regulate Microplastics? 10 Regional Level 10 Outer Banks, North Carolina 10 Other United States Regions 12 State Level 13 Country Level 14 United States 14 Other Countries 15 International Level 16 Conventions 16 Suggested World Ban 17 International Campaigns 18 What Solutions Already Exist? 22 Washing Machine Additives 22 Faucet Filters 23 Advanced Wastewater Treatment 24 Plastic Alternatives 26 What Should Be Done? 27 Policy Recommendations for North Carolina 27 Campaign Strategy for the North Carolina Coastal Federation 27 References 29 1 What are Microplastics? The category of ‘plastics’ is an umbrella term used to describe synthetic polymers made from either fossil fuels (petroleum) or biomass (cellulose) that come in a variety of compositions and with varying characteristics. These polymers are then mixed with different chemical compounds known as additives to achieve desired properties for the plastic’s intended use (OceanCare, 2015). Plastics as litter in the oceans was first reported in the early 1970s and thus has been accumulating for at least four decades, although when first reported the subject drew little attention and scientific studies focused on entanglements, ‘ghost fishing’, and ingestion (Andrady, 2011). Today, about 60-90% of all marine litter is plastic-based (McCarthy, 2017), with the total amount of plastic waste in the oceans expected to increase as plastic consumption also increases and there remains a lack of adequate reduce, reuse, recycle, and waste management tactics across the globe (GreenFacts, 2013). -

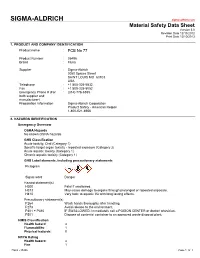

SIGMA-ALDRICH Sigma-Aldrich.Com Material Safety Data Sheet Version 5.0 Revision Date 12/13/2012 Print Date 12/10/2013

SIGMA-ALDRICH sigma-aldrich.com Material Safety Data Sheet Version 5.0 Revision Date 12/13/2012 Print Date 12/10/2013 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product name : PCB No 77 Product Number : 35496 Brand : Fluka Supplier : Sigma-Aldrich 3050 Spruce Street SAINT LOUIS MO 63103 USA Telephone : +1 800-325-5832 Fax : +1 800-325-5052 Emergency Phone # (For : (314) 776-6555 both supplier and manufacturer) Preparation Information : Sigma-Aldrich Corporation Product Safety - Americas Region 1-800-521-8956 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Emergency Overview OSHA Hazards No known OSHA hazards GHS Classification Acute toxicity, Oral (Category 1) Specific target organ toxicity - repeated exposure (Category 2) Acute aquatic toxicity (Category 1) Chronic aquatic toxicity (Category 1) GHS Label elements, including precautionary statements Pictogram Signal word Danger Hazard statement(s) H300 Fatal if swallowed. H373 May cause damage to organs through prolonged or repeated exposure. H410 Very toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. Precautionary statement(s) P264 Wash hands thoroughly after handling. P273 Avoid release to the environment. P301 + P310 IF SWALLOWED: Immediately call a POISON CENTER or doctor/ physician. P501 Dispose of contents/ container to an approved waste disposal plant. HMIS Classification Health hazard: 4 Flammability: 1 Physical hazards: 0 NFPA Rating Health hazard: 4 Fire: 1 Fluka - 35496 Page 1 of 7 Reactivity Hazard: 0 Potential Health Effects Inhalation May be harmful if inhaled. May cause respiratory tract irritation. Skin May be harmful if absorbed through skin. May cause skin irritation. Eyes May cause eye irritation. Ingestion May be fatal if swallowed. 3. COMPOSITION/INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS Synonyms : 3,3′,4,4′-PCB 3,3′,4,4′-Tetrachlorobiphenyl Formula : C12H6Cl4 Molecular Weight : 291.99 g/mol No ingredients are hazardous according to OHSA criteria. -

RESIDENTIAL ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS: a Guide for Homeowners, Homebuyers, Landlords and Tenants 2011

CALIFORNIA ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY RESIDENTIAL ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS: A Guide For Homeowners, Homebuyers, Landlords and Tenants 2011 This guide was originally developed by M. B. Gilbert Associates, under contract with the California Department of Real Estate in cooperation with the California Department of Health Services. The 2005 edition was prepared by the California Department of Toxic Substances Control, in cooperation with the California Air Resources Board and the California Department of Health Services, and meets all State and Federal guidelines and lead disclosure requirements pursuant to the Residential Lead-Based Paint Hazard Reduction Act of 1992. The 2005 edition incorporates the Federal “Protect Your Family from Lead” pamphlet. The 2011 update was developed California Department of Toxic Substances Control. This booklet is offered for information purposes only, not as a reflection of the position of the administration of the State of California. Residential Environmental Hazards Booklet Page 1 of 48 January 2011 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 3 CHAPTER I ASBESTOS 3 CHAPTER II CARBON MONOXIDE 10 CHAPTER III FORMALDEHYDE 13 CHAPTER IV HAZARDOUS WASTE 17 CHAPTER V HOUSEHOLD HAZARDOUS WASTE 21 CHAPTER VI LEAD 24 CHAPTER VII MOLD 31 CHAPTER VIII RADON 36 APPENDIX A LIST OF FEDERAL AND STATE AGENCIES 42 APPENDIX B GLOSSARY 46 Residential Environmental Hazards Booklet Page 2 of 48 January 2011 Introduction The California Departments of Real Estate and Health Services originally prepared this booklet in response to the California legislative mandate (Chapter 969, Statutes of 1989, AB 983, Bane) to inform the homeowner and prospective homeowner about environmental hazards located on and affecting residential property. -

Endocrine Disruption: Where Are We with Hazard and Risk Assessment? 2

1 Title: Endocrine disruption: where are we with hazard and risk assessment? 2 3 Running head: Hazard and risk assessment of endocrine disrupters 4 Katherine Coady*†, Peter Matthiessen‡, Holly M. Zahner§1, Jane Staveleyǁ; Daniel J. Caldwell#; 5 Steven L. Levine††, Leon Earl Gray Jr‡‡, Christopher J. Borgert§§ 6 7 † The Dow Chemical Company, Midland, MI, USA; 8 Telephone: 989-636-7423; Fax: 989-638-2425; e-mail: [email protected]; ‡Independent 9 Consultant, Llanwrtyd Wells, UK; e-mail: [email protected] ; § United States 10 Food and Drug Administration, Center for Veterinary Medicine, Rockville, MD, USA; email: 11 [email protected] ; ǁExponent Inc., Cary, NC, USA; email: [email protected] ; 12 #Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA; email [email protected] ; 13 ††Monsanto Company, St. Louis, MO, USA;email [email protected]; ‡‡USEPA, 14 ORD, NHEERL, TAD, RTB. RTP, NC, USA; email: [email protected] ; §§Applied 15 Pharmacology and Toxicology, Inc., and, Center for Environmental and Human Toxicology, 16 University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA; e-mail: [email protected] 17 1The views presented in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Food and Drug 18 Administration 19 * Corresponding Author: 20 Katherine Coady 21 The Dow Chemical Company, 1803 Building, Washington Street, Midland MI, USA, 48674. 22 Email address: [email protected] PeerJ Preprints | https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.2580v1 | CC0 Open Access | rec: 4 Nov 2016, publ: 23 24 ABSTRACT 25 Approaches to assessing endocrine disruptors (EDs) differ across the globe, with some 26 regulatory environments using a hazard-based approach, while others employ risk-based 27 analyses. -

Alternatives Assessment for Toxics Use Reduction: a Survey of Methods and Tools

THE MASSACHUSETTS TOXICS USE REDUCTION INSTITUTE Alternatives Assessment for Toxics Use Reduction: A Survey of Methods and Tools Methods and Policy Report No. 23 2005 University of Massachusetts Lowell Alternatives Assessment for Toxics Use Reduction: A Survey of Methods and Tools Prepared by: Sally Edwards Department of Work Environment University of Massachusetts Lowell Mark Rossi Clean Water Action and Pamela Civie Project Manager Toxics Use Reduction Institute Prepared for: The Massachusetts Toxics Use Reduction Institute University of Massachusetts Lowell The authors would like to acknowledge the significant contributions of the following: Gregory Morose, Maria Leet Socolof, and Joel Tickner All rights to this report belong to the Toxics Use Reduction Institute. The material may be duplicated with permission by contacting the Institute. The Toxics Use Reduction Institute is a multi-disciplinary research, education, and policy center established by the Massachusetts Toxics Use Reduction Act of 1989. The Institute sponsors and conducts research, organizes education and training programs, and provides technical support to promote the reduction in the use of toxic chemicals or the generation of toxic chemical byproducts in industry and commerce. Further information can be obtained by going to our website: www.turi.org, or by writing to the Toxics Use Reduction Institute, University of Massachusetts Lowell, One University Avenue, Lowell, Massachusetts 01854-2866. ©Toxics Use Reduction Institute, University of Massachusetts Lowell Table -

Assessment of Health Risk Associated with Persistent Organic Pollutants in Water

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Environ Monit Assess (2013) 185:497–508 DOI 10.1007/s10661-012-2570-8 Assessment of health risk associated with persistent organic pollutants in water Adam Pawełczyk Received: 9 October 2011 /Accepted: 10 February 2012 /Published online: 6 March 2012 # The Author(s) 2012. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This paper presents the results of analyses Keywords Environmental monitoring . Risk of water samples taken from water intakes supplying assessment . Polychlorinated biphenyls . one of the districts located near the city of Wrocław. Chloroorganic pesticides . Water pollution Surprisingly high concentrations of polychlorinated biphenyls and chloroorganic pesticides, classified as persistent organic pollutants (POPs), were detected in Introduction the monitored sites. Basing on the analytical and tox- icological data, the individual health risks related to Polychlorinated biphenyls and chloroorganic organic carcinogenic effects (excess cancer risk over a life- pesticides used on a massive scale in not so distant past time) in humans were assessed, resulting from direct still pose major health hazard to people and animals. ingestion of community water. Also noncarcinogenic Polychlorinated biphenyls are a mixture of congeners effects resulting from exposure to the examined POPs differing in their composition. Theoretically, 209 con- were determined. The conservative approach to risk -

Instructions for Completion of Environmental Hazard

INSTRUCTIONS FOR COMPLETION DEPARTMENT OF LABOR & INDUSTRY BUREAU OF WORKERS’ COMPENSATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARD SURVEY FORM The Environmental Hazard Survey Form is a document that provides information on Environmental Hazards listed on the Hazardous Substance Lists which are emitted, discharged or disposed of from a workplace. This information is to be provided to the extent that such information or reports are required under current provisions of federal, state, county or municipal law. In lieu of completing the Discharge/Emission of Environmental Hazards (Part II) and Hazardous Wastes (Part III) sections of this form, an employer may provide his/her list of environmental hazards and any reports or portions thereof, required by current provisions of federal, state, county or municipal law, which contains the information specified in the regulations. If you intend to attach these reports, complete only items 1 through 13. To determine if you are required to complete this form, answer YES or NO to the following questions: • Does your facility have any environmental hazards (EHs) present anywhere in your facility? Use your most recent Hazardous Substance Survey Form to determine the presence of environmental hazards. • If EHs were or are present in your facility, were or are any of them emitted, discharged, and/or disposed of from your facility? • Does your facility have any permits and/or waste manifests for these EHs from any federal, state or local government agency? • If you did not answer YES to all three questions, only complete Items 1 through 13 on the form and return. • If you did answer YES to all three questions, then you must complete Items 1 through 13 and attach copies of appropriate permits or manifests in lieu of completing Parts II and III. -

The Precautionary Principle: Protecting Public Health, the Environment and the Future of Our Children

The precautionary principle: protecting public health, the environment and the future of our children Edited by: Marco Martuzzi and Joel A. Tickner Keywords RISK ASSESSMENT RISK MANAGEMENT UNIVERSAL PRECAUTIONS CHILD WELFARE ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PUBLIC HEALTH SUSTAINABILITY ISBN 92 890 1098 3 Address requests about publications of the WHO Regional Office to: x by e-mail [email protected] (for copies of publications) [email protected] (for permission to reproduce them) [email protected] (for permission to translate them) x by post Publications WHO Regional Office for Europe Scherfigsvej 8 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark © World Health Organization 2004 All rights reserved. The Regional Office for Europe of the World Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications, in part or in full. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Where the designation “country or area” appears in the headings of tables, it covers countries, territories, cities, or areas. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

Environmental Hazards

Revised September 2012 Label Review Manual Chapter 8: Environmental Hazards , photo by “Daderot” photo , s.wikimedia.org n /commo http:/ Label Review Manual I. Introducn tio The Environmental Hazards statement provides the precautionary language informing users of the potential hazards to the environment from transport, use, storage, or spill of the product. These hazards may be to water, soil, air, beneficial insects, plants, and/or wildlife as identified in risk assessments performed by the Environmental Fate and Effects Division. Generally, the information contained in this section is based upon the results of eight basic acute toxicity studies performed on the technical grade of the active ingredient(s) in the formulation. These eight studies are: (1) avian oral LD50 (with mallard or bobwhite quail), (2) avian dietary LC50 (mallards), (3) avian dietary LC50 (bobwhite quail), (4) freshwater fish LC50 (rainbow trout), (5) freshwater fish LC50 (bluegill sunfish), (6) acute LC50 freshwater invertebrates (Daphnia magna or water flea), (7) honeybee contact LD50, and (8) mammalian acute oral LD50. For specific data requirements: 40 CFR Part 158. In addition, data concerning a product’s potential to be transported to groundwater, surface water, aquatic sediment, to drift, to adversely affect non-target plants and bees provide important information. Data include, but are not limited to, results from hydrolysis, batch equilibrium, aerobic soil metabolism, field dissipation, and prospective groundwater studies. The data generated from all of these studies support the language used for the Environmental Hazards statements. Review of the data is performed by the Environmental Fate and Effects Division (EFED) or other science reviewers who may also evaluate any label text proposed by the registrant to determine what statements are required. -

Health Concerns and Environmental Issues with PVC-Containing

Contractor’s Report to the Board Health Concerns and Environmental Issues with PVC-Containing Building Materials in Green Buildings Review of Current Practices and Trends in the Use, Recycling, and Disposal of PVC-Containing Building Materials Produced under contract by: California Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment October 2006 S TATE OF C ALIFORNIA Arnold Schwarzenegger Governor Linda S. Adams Secretary, California Environmental Protection Agency • INTEGRATED WASTE MANAGEMENT BOARD Margo Reid Brown Jeffrey Danzinger Rosalie Mulé Board Chair Board Member Board Member Cheryl Peace Gary Petersen Pat Wiggins Board Member Board Member Board Member • Mark Leary Executive Director For additional copies of this publication, contact: Integrated Waste Management Board Public Affairs Office, Publications Clearinghouse (MS–6) 1001 I Street P.O. Box 4025 Sacramento, CA 95812-4025 www.ciwmb.ca.gov/Publications/ 1-800-CA-WASTE (California only) or (916) 341-6306 Publication #432-06-016 Copies of this document originally provided by CIWMB were printed on recycled paper containing 100 percent postconsumer fiber. Copyright © 2006 by the California Integrated Waste Management Board. All rights reserved. This publication, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission. Prepared as part of contract number IWM-C0197, $38,655. The California Integrated Waste Management Board (CIWMB) does not discriminate on the basis of disability in access to its programs. CIWMB publications are available in accessible formats upon request by calling the Public Affairs Office at (916) 341-6300. Persons with hearing impairments can reach the CIWMB through the California Relay Service, 1-800-735-2929. Disclaimer: This report to the Board was produced under contract by the California Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. -

John M. Desesso, Ph.D., DABFM, DABFE, FACFEI, DABCHS, Fellow

John M. DeSesso, Ph.D., DABFM, DABFE, FACFEI, DABCHS, Fellow ATS Principal Scientist | Health Sciences 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 500 | Alexandria, VA 22314 (571) 227-7261 tel | [email protected] Professional Profile Dr. DeSesso has over 45 years of post-doctoral experience specializing in the areas of developmental and reproductive toxicology, general toxicology, risk assessment, and human health effects of environmental agents and pharmaceuticals. Dr. DeSesso's research has included normal and abnormal development, with emphasis on the mechanisms by which chemical and physical agents influence developing organisms. He has an ongoing interest in determining the mechanism, location and timing of the transplacental transfer of various substances (including small molecules and biologics) in various species. He has worked on projects including the assessment for potential gestational exposures to various substances to cause developmental or neurobehavioral effects, determination of the possible teratogenicity of atrazine and glyphosate, and demonstration of the mode of teratogenic action for an artificial blood substitute that is absent in humans. He is an adjunct professor of Biochemistry and Cellular & Molecular Biology at Georgetown University School of Medicine where he has taught embryology and anatomy for over 30 years. He has received 6 Teacher of the Year Awards (1 from the Medical College of Virginia School of Pharmacy; 5 from Georgetown University School of Medicine) and is the 2014 recipient of the Narsingh Agnish Fellowship from the Teratology Society, which recognizes contributions to education. He has been invited frequently to serve as the chairman of scientific sessions at national and international scientific meetings, especially those involving mechanisms or amelioration of developmental toxicity and human health risk assessment. -

Assessment of Chemical and Non-Chemical Alternatives: Focusing on Solutions

Assessment of Chemical and Non-Chemical Alternatives: Focusing on Solutions Foundation Paper for GCO II Chapter December 2018 Joel Tickner Molly Jacobs Nyree Bekarian Mack University of Massachusetts Lowell Lowell Center for Sustainable Production Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Moreover, the views expressed do not necessarily represent the decision or the stated policy of the United Nations Environment Programme, nor does citing of trade names or commercial processes constitute endorsement. Table of Contents Report Highlights .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction and Objectives ................................................................................................................. 3 2. Methods ................................................................................................................................................ 4 3. Understanding Informed Substitution and Alternatives Assessment .................................................. 5 4. Frameworks, Methods and Tools for Alternatives Assessment ......................................................... 10 5. Landscape of Requirements