Teratology Transformed: Uncertainty, Knowledge, and Cjonflict Over Environmental Etiologies of Birth Defects in Midcentury America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race and Membership in American History: the Eugenics Movement

Race and Membership in American History: The Eugenics Movement Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. Brookline, Massachusetts Eugenicstextfinal.qxp 11/6/2006 10:05 AM Page 2 For permission to reproduce the following photographs, posters, and charts in this book, grateful acknowledgement is made to the following: Cover: “Mixed Types of Uncivilized Peoples” from Truman State University. (Image #1028 from Cold Spring Harbor Eugenics Archive, http://www.eugenics archive.org/eugenics/). Fitter Family Contest winners, Kansas State Fair, from American Philosophical Society (image #94 at http://www.amphilsoc.org/ library/guides/eugenics.htm). Ellis Island image from the Library of Congress. Petrus Camper’s illustration of “facial angles” from The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. Inside: p. 45: The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. 51: “Observations on the Size of the Brain in Various Races and Families of Man” by Samuel Morton. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences, vol. 4, 1849. 74: The American Philosophical Society. 77: Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, Charles Davenport. New York: Henry Holt &Co., 1911. 99: Special Collections and Preservation Division, Chicago Public Library. 116: The Missouri Historical Society. 119: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882; John Singer Sargent, American (1856-1925). Oil on canvas; 87 3/8 x 87 5/8 in. (221.9 x 222.6 cm.). Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit, 19.124. -

An Assessment Report on Microplastics

An Assessment Report on Microplastics This document was prepared by B Stevens, North Carolina Coastal Federation Table of Contents What are Microplastics? 2 Where Do Microplastics Come From? 3 Primary Sources 3 Secondary Sources 5 What are the Consequences of Microplastics? 7 Marine Ecosystem Health 7 Water Quality 8 Human Health 8 What Policies/Practices are in Place to Regulate Microplastics? 10 Regional Level 10 Outer Banks, North Carolina 10 Other United States Regions 12 State Level 13 Country Level 14 United States 14 Other Countries 15 International Level 16 Conventions 16 Suggested World Ban 17 International Campaigns 18 What Solutions Already Exist? 22 Washing Machine Additives 22 Faucet Filters 23 Advanced Wastewater Treatment 24 Plastic Alternatives 26 What Should Be Done? 27 Policy Recommendations for North Carolina 27 Campaign Strategy for the North Carolina Coastal Federation 27 References 29 1 What are Microplastics? The category of ‘plastics’ is an umbrella term used to describe synthetic polymers made from either fossil fuels (petroleum) or biomass (cellulose) that come in a variety of compositions and with varying characteristics. These polymers are then mixed with different chemical compounds known as additives to achieve desired properties for the plastic’s intended use (OceanCare, 2015). Plastics as litter in the oceans was first reported in the early 1970s and thus has been accumulating for at least four decades, although when first reported the subject drew little attention and scientific studies focused on entanglements, ‘ghost fishing’, and ingestion (Andrady, 2011). Today, about 60-90% of all marine litter is plastic-based (McCarthy, 2017), with the total amount of plastic waste in the oceans expected to increase as plastic consumption also increases and there remains a lack of adequate reduce, reuse, recycle, and waste management tactics across the globe (GreenFacts, 2013). -

NIH Medlineplus Magazine Winter 2010

Trusted Health Information from the National Institutes of Health ® NIHMedlineWINTER 2010 Plusthe magazine Plus, in this issue! • Treating “ Keep diverticulitis the beat” Healthy blood Pressure • Protecting Helps Prevent Heart disease Yourself from Shingles • Progress against Prostate cancer • Preventing Suicide in Young Adults • relieving the Model Heidi Klum joins The Heart Truth Pain of tMJ Campaign for women’s heart health. • The Real Benefits of Personalized Prevent Heart Medicine Disease Now! You can lower your risk. A publication of the NatioNal Institutes of HealtH and the frieNds of the NatioNal library of MediciNe FRIENDS OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE Saying “Yes!” to Careers in Health Care ecently, the Friends of NLM was delighted to co-sponsor the fourth annual “Yes, I Can Be a Healthcare Professional” conference at Frederick Douglass Academy in Harlem. More than 2,300 students and parents from socioeconomically disadvantaged communities throughout the entire New York City metropolitan area convened for Rthe daylong session. It featured practical skills workshops, discussion groups, and exhibits from local educational institutions, health professional societies, community health services, and health information providers, including the National Library of Medicine (NLM). If you’ll pardon the expression, the enthusiasm among the attendees—current and future Photo: NLM Photo: healthcare professionals—was infectious! donald West King, M.d. fNlM chairman It was especially exciting to mix with some of the students from six public and charter high schools in Harlem and the South Bronx enrolled in the Science and Health Career Exploration Program. The program was created by Mentoring in Medicine, Inc., funded by the NLM and Let Us Hear co-sponsored by the Friends. -

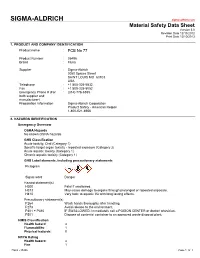

SIGMA-ALDRICH Sigma-Aldrich.Com Material Safety Data Sheet Version 5.0 Revision Date 12/13/2012 Print Date 12/10/2013

SIGMA-ALDRICH sigma-aldrich.com Material Safety Data Sheet Version 5.0 Revision Date 12/13/2012 Print Date 12/10/2013 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product name : PCB No 77 Product Number : 35496 Brand : Fluka Supplier : Sigma-Aldrich 3050 Spruce Street SAINT LOUIS MO 63103 USA Telephone : +1 800-325-5832 Fax : +1 800-325-5052 Emergency Phone # (For : (314) 776-6555 both supplier and manufacturer) Preparation Information : Sigma-Aldrich Corporation Product Safety - Americas Region 1-800-521-8956 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Emergency Overview OSHA Hazards No known OSHA hazards GHS Classification Acute toxicity, Oral (Category 1) Specific target organ toxicity - repeated exposure (Category 2) Acute aquatic toxicity (Category 1) Chronic aquatic toxicity (Category 1) GHS Label elements, including precautionary statements Pictogram Signal word Danger Hazard statement(s) H300 Fatal if swallowed. H373 May cause damage to organs through prolonged or repeated exposure. H410 Very toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. Precautionary statement(s) P264 Wash hands thoroughly after handling. P273 Avoid release to the environment. P301 + P310 IF SWALLOWED: Immediately call a POISON CENTER or doctor/ physician. P501 Dispose of contents/ container to an approved waste disposal plant. HMIS Classification Health hazard: 4 Flammability: 1 Physical hazards: 0 NFPA Rating Health hazard: 4 Fire: 1 Fluka - 35496 Page 1 of 7 Reactivity Hazard: 0 Potential Health Effects Inhalation May be harmful if inhaled. May cause respiratory tract irritation. Skin May be harmful if absorbed through skin. May cause skin irritation. Eyes May cause eye irritation. Ingestion May be fatal if swallowed. 3. COMPOSITION/INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS Synonyms : 3,3′,4,4′-PCB 3,3′,4,4′-Tetrachlorobiphenyl Formula : C12H6Cl4 Molecular Weight : 291.99 g/mol No ingredients are hazardous according to OHSA criteria. -

Eugenomics: Eugenics and Ethics in the 21 Century

Genomics, Society and Policy 2006, Vol.2, No.2, pp.28-49 Eugenomics: Eugenics and Ethics in the 21st Century JULIE M. AULTMAN Abstract With a shift from genetics to genomics, the study of organisms in terms of their full DNA sequences, the resurgence of eugenics has taken on a new form. Following from this new form of eugenics, which I have termed “eugenomics”, is a host of ethical and social dilemmas containing elements patterned from controversies over the eugenics movement throughout the 20th century. This paper identifies these ethical and social dilemmas, drawing upon an examination of why eugenics of the 20th century was morally wrong. Though many eugenic programs of the early 20th century remain in the dark corners of our history and law books and scientific journals, not all of these programs have been, nor should be, forgotten. My aim is not to remind us of the social and ethical abuses from past eugenics programs, but to draw similarities and dissimilarities from what we commonly know of the past and identify areas where genomics may be eugenically beneficial and harmful to our global community. I show that our ethical and social concerns are not taken as seriously as they should be by the scientific community, political and legal communities, and by the international public; as eugenomics is quickly gaining control over our genetic futures, ethics, I argue, is lagging behind and going considerably unnoticed. In showing why ethics is lagging behind I propose a framework that can provide us with a better understanding of genomics with respect to our pluralistic, global values. -

The Pioneering Efforts of Wise Women in Medicine and The

THE PIONEERING EFFORTS OF WISE WOMEN IN MEDICINE AND THE MEDICAL SCIENCES EDITORS Gerald Friedland MD, FRCPE, FRCR Jennifer Tender, MD Leah Dickstein, MD Linda Shortliffe, MD 1 PREFACE A boy and his father are in a terrible car crash. The father is killed and the child suffers head trauma and is taken to the local emergency room for a neurosurgical procedure. The attending neurosurgeon walks into the emergency room and states “I cannot perform the surgery. This is my son.” Who is the neurosurgeon? Forty years ago, this riddle stumped elementary school students, but now children are perplexed by its simplicity and quickly respond “the doctor is his mother.” Although this new generation may not make presumptions about the gender of a physician or consider a woman neurosurgeon to be an anomaly, medicine still needs to undergo major changes before it can be truly egalitarian. When Dr. Gerald Friedland’s wife and daughter became physicians, he became more sensitive to the discrimination faced by women in medicine. He approached Linda Shortliffe, MD (Professor of Urology, Stanford University School of Medicine) and asked whether she would be willing to hold the first reported conference to highlight Women in Medicine and the Sciences. She agreed. The conference was held in the Fairchild Auditorium at the Stanford University School of Medicine on March 10, 2000. In 2012 Leah Dickstein, MD contacted Gerald Friedland and informed him that she had a video of the conference. This video was transformed into the back-bone of this book. The chapters have been edited and updated and the lectures translated into written prose. -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

Camora 1.Pdf

The Function of the Rhetoric of Maternity in the Representation of Female Sexuality, Religion, Nationality, and Race in Early Modern English Literature and Culture by Cecilia Morales A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Schoenfeldt, Chair Dr. Neeraja Aravamudan, Edward Ginsberg Center, University of Michigan Professor Peggy McCracken Professor Catherine Sanok Professor Valerie Traub Cecilia Morales [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7428-3777 © Cecilia Morales 2020 Acknowledgements Throughout my doctoral studies, I have been fortunate to have the love and support of countless individuals, to whom I owe a great deal of gratitude. I’d like to begin by thanking my committee members. Cathy and Peggy taught me valuable lessons not only about my work but about being a thoughtful and compassionate scholar and teacher. Valerie’s reminders to always be as generous as possible when discussing the work of other scholars has kept me sane and stable in this competitive world of academia. Mike helped me, a displaced Texan, to feel at home in Michigan from our first meeting, during which we chatted about both Shakespearean scholarship and Tex Mex. Finally, the most recent addition to my committee is Neeraja Aravamudan, who I consider my most active mentor and supporter. One of the best decisions I made during graduate school was accepting an internship at the Edward Ginsberg Center, where Neeraja became my supervisor. Neeraja and the other Ginsberg staff remind me it’s possible to take my work very seriously without taking myself too seriously. -

Is There Life on Europa? Theses That Allow South African Runner Oscar Pistorius to Compete with Able-Bodied Athletes — Are Left to Later Sections

OPINION NATURE|Vol 457|22 January 2009 Superman born of a 1930s United States adopting eugenic practices, to the nuclear- powered Spider-Man of the cold-war era and the psychologically disturbed Batman incar- nations of the therapy-obsessed 1980s and 1990s, every generation has its super people. Those portrayed in Heroes are the genetically enhanced Generation X of the superhero world — too busy to save the world because their own lives are in perpetual turmoil. Societies get the superheroes they need most. Human Futures and The Science of Many of the ‘superpowers’ portrayed in the television series Heroes are no longer science fiction. Heroes give a tantalizing glimpse of how science might make this a reality in a future but misplaced essay on ‘evidence dolls’, the powers, such as the ability to steal memory, are human existence. And given Carts-Powell’s creation of designers Anthony Dunne and already with us in the form of drugs that help talent for explaining the science, perhaps an Fiona Raby. The plastic miniatures are a victims of trauma to forget. army of her clones will take over high-school hypothetical future product in which to store Historically, superheroes are a snapshot of education. ■ sperm and hair samples of prospective repro- the relationship between science and society Arran Frood is a science writer based in the NBC UNIVERSAL PHOTO ductive partners. The dolls are personified by at any one time, based on their powers and United Kingdom. four women, who reveal how knowledge of how they obtained them. From the perfect e-mail: [email protected] their partner’s genes might influence their sexual and reproductive lifestyles. -

Elementis Chromium Inc., ) Docket No

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY BEFORE THE ADMINISTRATOR In the Matter of: ) ) Elementis Chromium Inc., ) Docket No. TSCA-HQ-2010-5022 f/k/a Elementis Chromium, LP, ) ) Respondent. ) INITIAL DECISION Pursuant to Section 16 of the Toxic Substances Control Act, 15 U.S.C. § 2615, a penalty in the amount of $2,571,800 is hereby imposed against Respondent Elementis Chromium, Inc., f/k/a Elementis Chromium, LP, for noncompliance with Sections 8(e) and 15(3)(B) of the Toxic Substances Control Act, 15 U.S.C. § 2607(e) and § 2614(3)(B). DATED: November 12, 2013 PRESIDING OFFICER: Chief Administrative Law Judge Susan L. Biro APPEARANCES: For Complainant: For Respondent: Mark A.R. Chalfant, Esq. John J. McAleese, III, Esq. Environmental Protection Agency (Formerly Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, LLP) 1595 Wynkoop Street (8ENF-L) 1735 Market Street, Suite 700 Denver, CO 80202 Philadelphia, PA 19103 (303) 312-6117 (215) 979-3892 Erin K. Saylor, Esq. Ronald J. Tenpas, Esq. Environmental Protection Agency Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, LLP 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. 1111 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. WJC Building: MC 2249A Washington, DC 20004 Washington, DC 20460 (202) 739-5435 (202) 564-6124 I. PROCEDURAL HISTORY On September 2, 2010, Rosemarie A. Kelley (“Complainant”), Director of the Waste and Chemical Enforcement Division, Office of Civil Enforcement, United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA” or “Agency”), filed a Complaint and Notice of Opportunity for Hearing (“Complaint”) pursuant to Section 16(a) of the Toxic Substances Control Act (“TSCA”), 15 U.S.C. § 2615(a), and the Consolidated Rules of Practice Governing the Administrative Assessment of Civil Penalties and the Revocation/Termination or Suspension of Permits, set forth at 40 C.F.R. -

Developmental Biology, Genetics, and Teratology (DBGT) Branch NICHD

The information in this document is no longer current. It is intended for reference only. Developmental Biology, Genetics, and Teratology (DBGT) Branch NICHD Report to the NACHHD Council September 2006 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health National Institute of Child Health and Human Development The information in this document is no longer current. It is intended for reference only. Cover Image: The figures illustrate several of the animal model organisms used in research supported by the DBGT Branch including: the fruit fly, Drosophila (top, left); the zebrafish, Danio (top, middle); the frog, Xenopus (top, right); the chick, Gallus (bottom, left); and the mouse, Mus (bottom, middle). The human baby (bottom, right) represents the translational research on human birth defects. Drawings by Lorette Javois, Ph.D., DBGT Branch The information in this document is no longer current. It is intended for reference only. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... 1 BRANCH PROGRAM AREAS .......................................................................................................... 1 BRANCH FUNDING TRENDS.......................................................................................................... 2 HIGHLIGHTS OF RESEARCH SUPPORTED AND BRANCH ACTIVITIES.............................................. 3 FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR THE DBGT BRANCH .......................................................................... -

CURRICULUM VITAE for ACADEMIC PROMOTION the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

CURRICULUM VITAE FOR ACADEMIC PROMOTION The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Larry William Chang, MD, MPH (Signature) _____________________________ July 2, 2014 (Typed Name) Larry William Chang (Date of this version) DEMOGRAPHIC AND PERSONAL INFORMATION Current Primary Appointment Assistant Professor Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Baltimore, MD Joint Appointments Social and Behavioral Interventions Program, Department of International Health Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Baltimore, MD Department of Epidemiology Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Baltimore, MD Personal Data Business Address 725 N. Wolfe Street, Suite 216 Baltimore, MD 21205 Phone: (410) 929-2001 Fax: (410) 685-0031 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION AND TRAINING Undergraduate 1997 B.A., English Emory University, Atlanta, GA 1997 B.A., Biology Emory University, Atlanta, GA Doctoral/graduate 2002 M.P.H., Epidemiology Emory University Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA 2002 M.D., Medicine Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA Postdoctoral 2002-2005 Internship/Residency University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 2006-2009 I.D. Fellowship Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Dates Positions and Institutions 2002-2003 Categorical Internal Medicine Intern, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 2003-2005 Categorical Internal Medicine Resident, Department