Altaf Baghdadi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P19 Layout 1

TUESDAY, MAY 5, 2015 SPORTS FIFA to study Israel-Palestinians dispute on election day GENEVA: A move to consider suspend- for restrictions imposed by security forces international matches and meetings, and President Prince Ali bin al-Hussein of to the 2014 World Cup. They will also ing Israel from world football will be put which limit movement of players, oppos- block FIFA funding. The FIFA election is Jordan, Netherlands federation head elect replacement officials for FIFA judicial to FIFA’s 209 member federations just ing teams and equipment. the final main item of business on the Michael van Praag and Luis Figo, the for- bodies. After former United States federal before they elect their president this Earlier in the meeting in Zurich, Blatter annual congress agenda. Blatter is strong- mer Portugal, Barcelona and Real Madrid prosecutor Michael Garcia resigned in month. - who met several times in recent weeks ly favored to win and extend his 17-year playmaker. FIFA election rules allow each protest last December as head of FIFA FIFA published an agenda yesterday with Palestinian football leader Jibril presidential reign at the age of 79. In a candidate to “speak for 15 minutes to ethics investigations, his Swiss deputy for its election congress on May 29, Rajoub - is scheduled to update on his note to the agenda, Blatter wrote “there is present their program to the congress.” Cornel Borbely should formally be elect- including a late proposal by Palestinian mediation between the two federations. always much work to do in maintaining Other congress business includes approv- ed into a position he has held on an inter- football officials to suspend Israel. -

SRTRC-ANN-REV-2010.Pdf

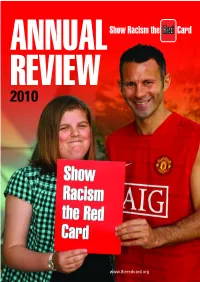

ANNUAL REVIEW 2010 www.theredcard.org SHOW RACISM THE RED CARD MAJOR SPONSORS: SHOW RACISM THE RED CARD DVD and education pack £25 (inc p&p) The DVD is a fast moving and engaging 22 minutes exploration of racism, its origins, causes and practical ways to combat it. The film includes personal experiences of both young people and top footballers, such as Ryan Giggs, Thierry Henry, Rio Ferdinand and Didier Drogba. The education pack is filled with activities and discussion points complete with learning outcomes, age group suitability and curriculum links. SPECIAL OFFER: Buy ‘SHOW RACISM THE RED CARD’ with ‘ISLAMOPHOBIA/ A SAFE PLACE’ for a special price of £45 including p&p. For more information or to place an order email www.theredcard.org ANNUAL REVIEW 2010 FOREWORD CONTENTS Shaka Hislop, Honorary President Foreword by Shaka Hislop 1 What a year it has been for Show Racism the Red Card. Football crowds and club revenues continue to rise steadily Introduction by Ged Grebby 3 despite much of the world still gripped by the recession. Many people believe, and will say out loud, that football has Sponsorship 4 its own world. As the growing crowds also show an increase in the number of minority groups regularly attending games every weekend, a few ask ‘why the need Website 5 for an organisation such as Show Racism The Red Card?’ The stats speak for themselves. This has been a record year Leroy Rosenior 6 in terms of revenues raised and staff growth at well over 15%. The website also continues to show amazing growth Hall of Fame 7 and popularity and even on Facebook the fan numbers are very pleasing indeed. -

Virginia Grab First CWS Title Virginia Down Vanderbilt for College World Series Title

Souq Al-Mubarakiya Virginia oldest in Kuwait grab first Emsak: 03:03 Fajer: 03:15 CWS title Dohr: 11:51 Asr: 15:24 Maghreb: 18:51 4 47 Eshaa: 20:24 Min 29º Max 46º FREE www.kuwaittimes.net NO: 16563- Friday, June 26, 2015 Page 39 PARIS: Demonstrators try to flip an alleged minicab, known in France as VTC (Voitures de Tourisme avec Chauffeurs), at Porte Maillot in Paris yesterday, as hundreds of taxi drivers converged on airports and oth- er areas around the capital to demonstrate against UberPOP, a popular taxi app that is facing fierce oppo- sition from traditional cabs. — AFP Local FRIDAY, JUNE 26, 2015 IN MY VIEW The Meaning of Life Top 10 reasons od says in the Quran, “And We did not create the earned, and they will not be wronged.” (45:22) to celebrate heaven and the earth and that between them • “Do the people think they will be left to say, ‘We Gaimlessly. That is the assumption of those who believe’ and that they will not be tried?” (29:1) Ramadan in Kuwait disbelieve...” (38:27). He clearly states that he created • “You will surely be tested in your possessions and mankind to worship Him (51:56). However, in addition to yourselves.” (3:186) By Sara Ahmed worship through prayer or fasting the month of Ramadan, The challenges of life facilitate our growth in areas for example, any lawful and moral activity done with the such as self-awareness, so we acknowledge our limita- [email protected] intention of pleasing God is also regarded as worship, tions and need for God; mental capacities, so we under- such as studying, performing on-the-job tasks, nursing a stand the nature of good and evil; social responsibility, child, exercising, building friendships, and so forth. -

The First Professional Asian Darts Player on the Full BDO Circuit

46 Asian Express National JANUARY 1ST EDITION 2011 SPORT www.asianexpress.co.uk www.asianexpress.co.uk SPORT JANUARY 1ST EDITION 2011 Asian Express National 47 SEND US YOUR SPORTS STORIES TO SPORT @ASIANEXPRESS.CO.UK REF GIVES HIMSELF THE RED CARD From non-league to international star The pioneer of Asian A student from West Yorkshire really exciting, I was going to make Association (PFF) in attendance. referees retires has been called up to the my debut at the Asian Games but I Irfan, who currently plays for a Pakistan football team for the had just started university and local Bradford side, Mahmoods Back page story forthcoming Olympic decided not to take time out. Fairbank United, was first selected in qualifiers against “Graham Roberts is now in charge 2007 and was included in the U19’s Coventry vs Stoke. It was my first Malaysia. and to be honest I am excited to squad for a tournament in Iran, LAE BULLSEeYE: The firstt ’s play darts! Championship game and it was Irfan Khan, 21, work with him, he brings a lot to making five appearances. professional Asian darts a very tough but a great from Bradford, Pakistan. He was also called up for a player showing why he experience.” maybe just a “We are travelling to Thailand on training camp with the main earned the nickname ‘Rock It’ “There were a few years where regular student the February 6th, for two week camp Pakistan team but was forced to I stopped refereeing, when I studying sports Brian Robson he is the manager of withdraw due to injury and is yet to moved to London. -

Kick It out Annual Report

Kick It Out Annual Report www.kickitout.org Kick It Out Unit 3, 1–4 Christina Street London EC2A 4PA Telephone 0207 684 4884 Email [email protected] Visit www.kickitout.org IGN S Kick It Out is supported and funded by E the game’s governing bodies, including the Professional Footballers Association (PFA), the Premier League, the Football EDWARD Foundation and The Football Association ANDY Introduction Kick It Out is about promoting positive attitudes These activities are having an impact because amongst everyone involved in football to there remains an appetite to ensure both good achieve equality and fair treatment for people corporate governance and that football embraces of all backgrounds. all people, whatever their race, background or Already well into a second decade of campaigning gender, whether they are disabled or not, straight as football’s equality and inclusion partner, many or gay, young or old. Football has a unique appeal things have been achieved with the help of many and therefore unique opportunities to involve people. So much so that it feels like we live in and engage. a different era to the one in which I worked with As we move on in our agenda to ensure that colleagues at the PFA to launch the organisation equality is embedded in the game, we move onto in the face of rampant racial abuse on and off the different and more complex questions. One might field of play. say we are at a pivotal point. These achievements have only been possible Questions remain about how football can Developing Talent with the support of countless individuals and continue to set an example and ensure that all organisations, foremost amongst whom are our communities and all types of people can be funding partners — the Professional Footballers’ offered equal access to the many opportunities Anti-discrimination Association, the Premier League, the Football football offers — on the field of play, in Foundation and The Football Association. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Pakistan Football Captain Zesh Rehman to train young people at Belleek Park Multi-Sports Event on 20th October. Ex-Fulham and QPR and Bradford City Player to train local young people at Belleek Park Zesh took his football Uefa A Licence with the Northern Irish FA Zesh will also attend the Gala Dinner at the Great National Hotel Ballina in the evening. We are excited to announce that Pakistan Football Captain Zesh Rehman will be coaching local young people at a multi-sport event, taking place at Belleek Park from 1:30pm on the 20th October. Zesh, who set up the Zesh Rehman Foundation (ZRF) as a not for profit organisation in 2010, is a great advocate of the effect that sport can have on young people stating that; “football has the power to inspire young people from marginalised communities to triumph in the face of adversity. With a clear focus, incessant hunger for success, commitment, humility and faith one can achieve anything in this world.” Zesh will be contributing to several of the networking discussions on how sport can be used to develop young people in communities with a particular focus on sport as a driver for cohesion, stability and resilience, in particular, learning from Active Communities Network experiences in Belfast. As a Pakistan Football Captain Zesh will add significant international experience and input to this event and we are excited to be working in this context. Zesh Rehman who is flying in from Brunei to attend the event said; ‘I am looking forward to attending the event in Ballina to see the fantastic work being done across Ireland, get to know more about the work of Laureus, Active Communities and the Mary Robinson Foundation in using sport to support the UN’s sustainable development goals, and to take some of the best practice being promoted from Ireland and applying it through my own Foundation across Asia.’ Notes to Editors: 1. -

FA Asians in Football Newsletter

IMAGE NEWSLETTER ISSUE 1 DEVELOPING ASIAN FOOTBALL. HEADING SUBHEADING. THEFA.COM | © THE FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION 1 As the governing body of football, The FA has a duty to make the game more inclusive. Not only that, we have committed through the Inclusion and Anti-Discrimination Plan to take steps that will make change happen. The under representation of Asian communities across the whole game has been recognised as a priority area for The FA and through this newsletter, alongside a number of other activities and strategies, we hope to affect change. Clearly, such change will not happen overnight, real change will involve all of the game’s stakeholders working collectively to continue to break down barriers and make sure that football truly is accessible for everyone who wishes to get involved. Alex Horne, General Secretary The Football Association THEFA.COM | © THE FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION 2 CONTENTS Development news 4-6 Faces in football 7 Sport & exercise medicine 8 Reporting discrimination 9 Community events 10-11 Career opportunities 12 Funding 13-14 Events 15 THEFA.COM | © THE FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION 3 DEVELOPMENT NEWS THE FA’s ASIANS IN FOOTBALL PLANS AND VISION As part of English Footballs commitment to inclusion and 6. Ensuring that the number of coaches from Black, Asian, diversity across the whole game, the Inclusion & Anti- and Minority Ethnic communities, who are accessing the Discrimination Plan includes several targets around increasing Level 1 and 2 coaching qualifications, remains reflective the representation, participation and progress of Asians across of national demographics and does not fall below 10% of the game: the total number of coaches qualified at these levels. -

3 Asians Missing Mekunu Wreaked Havoc in Yemen’S Socotra Island, Killing 7

RAMADAN 11, 1439 AH SUNDAY, MAY 27, 2018 Max 45º 28 Pages Min 28º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 17542 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Ireland ends abortion ban; ‘quiet War, displacement reshuffle revolution’ transforms country the Syrian demographic map Super Bale sinks Liverpool; 6 7 28 Madrid make it 3 in a row IMSAK 03:08 FAJR 03:19 DHUHR 11:45 ASR 15:20 MAGHRIB 18:40 ISHA 20:10 2 killed as Cyclone Mekunu hits Oman; 3 Asians missing Mekunu wreaked havoc in Yemen’s Socotra Island, killing 7 SALALAH: Cyclone Mekunu was downgraded further Ramadan Kareem to a deep depression yesterday, a day after lashing the southern coast of Oman and killing at least two people, authorities said. Civil defense officials said a man and a 3 parts of Ramadan 12-year-old girl were killed, while three Asians were missing after the cyclone hit Oman’s Dhofar and Al- Wusta provinces. Oman police earlier reported that the By Teresa Lesher man died after floods swept him away with his car near amadan is said to be split into three thirds: the Salalah, Oman’s second-largest city, while the girl died Holy Prophet (PBUH) has said, “It (Ramadan) when a gust of wind smashed her into a wall. is the month whose beginning is mercy, mid- Mekunu, which has wreaked havoc in Yemen’s R Socotra island killing at least seven people, was head- dle, forgiveness and its end emancipation from the fire” (Bihar Al-Anwar, Vol 93). Salman Al-Farisi (RA) ing northwest to Saudi Arabia, Oman’s directorate of reported that Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) meteorology said. -

Stand up Against Racism 30 the Pentagon Centre Than the School Children My Teammates and I Spoke PO Box 141, Whitley Bay to in Those Early Days

ANNUAL REVIEW www.theredcard.org 2011 SHOW RACISM THE RED CARD ANNUAL REVIEW 2011 MAJOR SPONSORS CONTENTS FOREWORD Foreword by Shaka Hislop 1 SHAKA CAMPAIGN 2 HISLOP Introduction by Ged Grebby 3 Honorary Campaign Team England President by Paul Kearns 5 It takes courage Website and Social Networking to make the first by Laura Hagan 7 step and then 15th Anniversary Celebration 8 determination to continually Hall of Fame 9 take the next. It Resources by Tony Waddle 10 seems like only yesterday that Educational Events I replied to a by Gavin Sutherland 12 letter and Teacher Training by Jo Wallis 18 wrote a small New Research: ‘The Barriers to cheque, Tackling Racism and Promoting which Equality in England’s Schools’ unknowingly by Sarah Soyei 20 saw me embark on a Education in England 22 journey that was as awe-inspiring as it was CONTACT: Burning Questions by Laura Pidcock 27 rewarding. Aided and encouraged by some of the Annual Showcase for East & best people I have ever met; that journey sees me South East England 29 here today. Along the way I have been encouraged SHOW RACISM THE RED CARD SHOW RACISM THE RED CARD SCOTLAND and inspired by a number of people. None more so Stand Up Against Racism 30 The Pentagon Centre than the school children my teammates and I spoke PO Box 141, Whitley Bay to in those early days. That was almost 15 years ago, Suite 311 Stand Up Against Racism Wales 31 Tyne & Wear and I shudder to think that they are all young men and UK Parliamentary FC v Show Racism NE26 3YH Washington Street women now. -

Raise Your Game 2017 Mentor Biographies 1. Media And

Raise Your Game 2017 Mentor Biographies (Mentors are subject to change) 1. Media and Communications Page 2 2. Coaching and Management Page 11 3. Grassroots and Community Page 15 4. Player Services Page 21 5. Refereeing Page 23 6. Sports Science Page 24 7. Football Administration Page 25 1 1. Media and Communications Tom Adams Deputy Managing Editor of website and app Eurosport Twitter: @tomEurosport Tom is the deputy managing editor of the Eurosport website and mobile app, overseeing news, feature, video and social media output. He has been working in digital sports newsrooms for over 10 years, including spells with ESPN, Sky Sports and the BBC amongst others. Justin Allen Sports Journalist The Sun Twitter: @justinallen1976 Justin is a football writer for The Sun, having previously worked for The News of the World, The Times, Daily Express, Daily Star, Daily Mirror, the Evening Standard and BBC Radio Kent. He started his career at the East Kent Mercury at the age of 19 and was named Kent Young Journalist of the Year in 1998 before winning the BT Regional Sports Writer of the Year in 1999. Justin also worked for two years at the Evening Argus in Brighton between 1999-2001. Nemesha Balasundaram Sub-Editor Sky Sports News Twitter: @NemeshaB Nemesha is a sub-editor at Sky Sports News, where she produces video content for the TV channel across a variety of sports including football, cricket, boxing and Formula 1. Her role also involves writing stories and TV scripts to strict deadlines. Previously, Nemesha worked as a news and sports reporter at The Irish Post across its digital and print platforms. -

Racism in Football

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee Racism in Football Second Report of Session 2012–13 Volume I Volume I: Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 11 September 2012 HC 89 Published on 19 September 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr John Whittingdale MP (Conservative, Maldon) (Chair) Dr Thérèse Coffey MP (Conservative, Suffolk Coastal) Damian Collins MP (Conservative, Folkestone and Hythe) Philip Davies MP (Conservative, Shipley) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Steve Rotheram MP (Labour, Liverpool, Walton) Mr Adrian Sanders MP (Liberal Democrat, Torbay) Jim Sheridan MP (Labour, Paisley and Renfrewshire North) Mr Gerry Sutcliffe MP (Labour, Bradford South) Mr Tom Watson MP (Labour, West Bromwich East) The following member was also a member of the committee during the parliament: Louise Mensch (Conservative, Corby) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/cmscom. -

On the Board

ON THE main sponsor of BOARD on the board from the pitch to the boardroom Working together to usher in a new era of diversity at football’s top table CONTENTS 07 For THe 20 GovernAnce ForUm Elizabeth Muir For THe pFA Oshor Williams FUTUre FUsion senior editor Lee Hart Art director Dermot Rushe 28 contributing editor Lee Hall photography PA Photos, Click Jones, Joe Branston commercial manager 04 welcome 22 sUrrey coUnTy FA Mike Vincent From Karl George MBE, creator of the The importance of ensuring your Effective Board Member programmes and organisation is fully representative of those On The Board is published on behalf of the PFA Chief Executive Gordon Taylor OBE. playing the game. Governance Forum and the Professional Footballers Association by Future Fusion, a division of Future Publishing THe FA TridenT Ltd. Registered office: Quay House, The 07 23 Ambury, Bath, BA1 1UA. Companies/ Greg Dyke and Dame Heather Rabbatts The innovative housing provider has found individuals included in this publication does explain why the game’s governing body is numerous benefits in being an Effective not imply endorsement by the Governance firmly behind On The Board. Board Member supporter. Forum, the PFA or the Publisher. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the consent of the PFA. 08 FerdinAnd & rAmsey 24 joHnny erTl Graduates Les Ferdinand and Chris Ramsey The ex-Portsmouth star and On The Board explain how On The Board has helped alumni is using the skills he’s learned on the them in their directorial roles at QPR.