Reasonable Discrimination Policy”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internal and External Security Dynamics of Qatari Policy Toward the Syria Uprising

Comillas Journal of International Relations | nº 05 | 065-077 [2016] [ISSN 2386-5776] 65 DOI: cir.i05.y2016.005 INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL SECURITY DYNAMICS OF QATARI POLICY TOWARD THE SYRIA UPRISING Las dinámicas de seguridad internas y externas de la política de Catar frente al levantamiento sirio Kristian Coates Ulrichsen Fellow for the Middle East, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy Autor Affiliate Professor, Henry M Jackson School of International Studies, University of Washington-Seattle E-mail: [email protected] Qatar played a leading role in supporting the opposition to Bashar al-Assad since the beginning of the Syrian uprising in 2011. While Kuwait emerged as a key (unofficial) conduit for financial Abstract transfers from the Gulf States to Syria and backing from Saudi Arabia initially took the form of illicit flows of militants and weapons to groups of opposition fighters, Qatar from the start adopted a political approach to organizing the Syrian opposition, in addition to providing tens of millions of dollars to rebel groups. Qatari support increasingly controversial as it was perceived to be tied to groups linked to the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood. During 2012, Qatar and Saudi Arabia backed competing groups, contributing to the fragmentation of the opposition, before responsibility for the “Syria file” passed decisively from Doha to Riyadh in spring 2013. This signified a major setback to Qatar’s ambition to become a regional power and highlighted how Qatar’s Syria policy was undermined by the lack of institutional capacity to underpin highly- personalised decision-making processes. Qatar; Syria; Saudi Arabia; Syrian civil war; Syrian opposition; rebel groups; terrorism financing; Key words foreign policy Catar; Siria; Arabia Saudí; guerra civil siria; oposición siria; grupos rebeldes; financiación del terrorismo; política exterior Recibido: 25/9/2015. -

Expanding the Space(S)”: Thoughts on Law, Nationalism and Humanism – Following the Bishara Case1

“Expanding the Space(s)”: Thoughts on Law, Nationalism and Humanism – Following the Bishara Case1 Barak Medina and Ilan Saban In February 2006, the Supreme Court of Israel majority of members of the Arab minority ruled that Azmi Bishara, a former Member of limits the assistance it tries to extend to its Knesset (MK), should not be criminally people to the methods permitted by Israeli law: prosecuted for speeches he made several years parliamentary, legal and civil-political struggle, ago in which he praised Hezbollah for its participation in the public discourses (the success in the fight against the Israeli military Israeli, the Palestinian, the pan-Arab and the in southern Lebanon and expressed support global), material contributions to the needy for the “resistance” to the Occupation. The and so forth. Nonetheless, within the Supreme Court determined that MK Bishara’s Palestinian Arab minority there exists a range remarks fell within the immunity accorded to of views pertaining to questions that lie at the MKs with regard to “expressing a view … in heart of the conflict: What are the goals of the fulfilling his role.” The case against MK Bishara Palestinian people’s struggle? And what are the was the first in which an indictment was filed legitimate means of attaining these goals? First, 29 against an MK for expressing a political view, should the “two-state solution” be adopted and and therefore the ruling was very important settled for? Or should there also be an assertive for determining both the scope of the material aspiration for a comprehensive realization of immunity enjoyed by MKs and the protection the right of return of the 1948 refugees and of free speech in general. -

Bernard Sabella, Bethlehem University, Palestine COMPARING PALESTINIAN CHRISTIANS on SOCIETY and POLITICS: CONTEXT and RELIGION

Bernard Sabella, Bethlehem University, Palestine COMPARING PALESTINIAN CHRISTIANS ON SOCIETY AND POLITICS: CONTEXT AND RELIGION IN ISRAEL AND PALESTINE Palestinian Christians, both in the Palestinian Territories (Palestine) and in Israel, number close to 180,000 altogether. Close to 50,000 of them live in the Palestinian Territories while roughly 130,000 live in Israel. In both cases, Christian Palestinians make up less than 2 percent of the overall population. In Israel, Christians make up 11% of the Arab population of over one million while in Palestine the Christians make up less than two percent (1.7%) of the entire population of three million. (1). In 1995 a survey of a national sample of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza on attitudes to society, politics and economics was conducted. It included surveying a group of 340 Christians from different localities in the West Bank and Gaza. (2). This survey provided a basis for comparing attitudes of Christians to those of their Muslim compatriots. In March 2000, a survey was conducted for the purpose of comparing the attitudes of Palestinian Christians in both Palestine and Israel. The same questionnaire was used, except for some modifications, in both the 1995 and 2000 surveys. (3). While the two surveys do not add up to a longitudinal study they, nevertheless, provide a basis to compare between two samples of Palestinian Christians in Palestine in 1995 and 2000 and between Palestinian Christians in Palestine and Israel for the year 2000. The responses of Muslim Palestinians in the 1995 survey also provide an opportunity to compare their responses with those of Christians in Israel and Palestine. -

The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: a Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2014 The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: A Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel Samira Abunemeh University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Abunemeh, Samira, "The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: A Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel" (2014). Honors Theses. 816. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/816 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: A Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel ©2014 By Samira N. Abunemeh A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2014 Approved: Dr. Miguel Centellas Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen Reader: Dr. Vivian Ibrahim i Abstract The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: A Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel Israeli Arab political parties are observed to determine if these ethnic political parties are successful in Israel. A brief explanation of four Israeli Arab political parties, Hadash, Arab Democratic Party, Balad, and United Arab List, is given as well as a brief description of Israeli history and the Israeli political system. -

Ibn Rushd Fund for Freedom of Thought to Azmi Bishara

Press Release Ibn Rushd Fund for Freedom of Thought to Azmi Bishara The Ibn Rushd Fund for Freedom of Thought awards its prize this year to Dr. Azmi Bishara, an Arab member of the Israeli Knesset. The prize, awarded for special contributions to freedom of speech and democracy in the Arab World, will be presented on Saturday 14th December 2002 in the German capital Berlin. The Ibn-Rushd Fund, named after the philosopher Ibn Rushd (1126-1198, a.k.a. Averroes), supports freedom of speech and democracy in the Arab World by awarding this prize. The thematic focus varies annually: so far, people from the fields of journalism, women's rights and humanities were honoured. This year, the prize will be awarded to an Arab personality who has shown special commitment to promoting democracy as a member of parliament. An independent jury elected Dr. Azmi Bishara. The Palestinian intellectual, born in Nazareth in 1956, is an Israeli citizen. Since 1996, he has been a member of the Knesset. Bishara started to be engaged in political activities already as a high school student; as a university student, he co-founded the Union of Arab Students, the first political organisation of this kind in Israel. From 1980 to 1985, he studied Philosophy and Political Science at the Humboldt-University in Berlin In Ramallah, West Bank, he co-founded the Institute for Democracy and was involved in publishing many important studies in the field of research on democracy. From 1986 to 1996 held a chair for Cultural Sciences, Philosophy and Political Theory at Bir Zeit University near Ramallah, West Bank. -

Forgotten Palestinians

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 THE FORGOTTEN PALESTINIANS 10 1 2 3 4 5 6x 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 36x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 36x 1 2 3 4 5 THE FORGOTTEN 6 PALESTINIANS 7 8 A History of the Palestinians in Israel 9 10 1 2 3 Ilan Pappé 4 5 6x 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS 5 NEW HAVEN AND LONDON 36x 1 In memory of the thirteen Palestinian citizens who were shot dead by the 2 Israeli police in October 2000 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 Copyright © 2011 Ilan Pappé 6 The right of Ilan Pappé to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by 7 him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 8 All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright 9 Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from 20 the publishers. 1 For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, 2 please contact: U.S. -

Where, Where To, and When in the Occupied Territories: an Introduction to Geography of Disaster

Where, Where to, and When in the Occupied Territories: An Introduction to Geography of Disaster Ariel Handel Over the past nineteen months since the Intifada began my space has been con- stantly narrowing. First it became too dangerous to go for walks in the hills around Ramallah, then I stopped being able to drive to Israel, then driving between the Pal- estinian towns and villages was prohibited. Now I cannot even step outside the door of my house. The perimeters of my house are all that is left for me of Palestine that I can call my own, and even this is not secure. — Raja Shehadeh, When the Bulbul Stopped Singing: A Diary of Ramallah under Siege Therefore, the people planning weddings in this country—may their numbers increase—designed invitations that included all the information about their beloved daughter or son . the announcement of the wedding and its location, everything except the details of when the joyous event would take place—the day of the week, the date, and the hour. All these were to be added by hand, in keeping with the cir- cumstances. Only when the curfew was lifted would they fill in the missing details on the invitation and send it as quickly as possible to the invitees. This new custom includes writing three or four dates, and the invitee knows that should a curfew be called on the first date . then the event will take place on the next date, and so on. —Azmi Bishara, Yearning in the Land of Checkpoints Space has been at the core of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict since the beginning of Zionism. -

Transitional Justice and Post-Conflict Israel/Palestine: Assessing the Applicability of the Truth Commission Paradigm, 38 Case W

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 38 Issue 2 2006-2007 2007 Transitional Justice and Post-Conflict Israel/ Palestine: Assessing the Applicability of the Truth Commission Paradigm Ariel Meyerstein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Ariel Meyerstein, Transitional Justice and Post-Conflict Israel/Palestine: Assessing the Applicability of the Truth Commission Paradigm, 38 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 281 (2007) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol38/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE AND POST-CONFLICT ISRAEL/PALESTINE: ASSESSING THE APPLICABILITY OF THE TRUTH COMMISSION PARADIGM Ariel Meyerstein * Redemption lies in remembering. The Baal Shem Tov I. INTRODU CTION .....................................................................................282 II. UNDERSTANDING THE REALITY OF INTERCONNECTIVITY ...................285 A. Interconnectivity and the "Peace& ProsperityParadigm .........285 B. The CurrentMoment: Paralysis.................................................... 291 C. The Conflict Culture, Victim Ideologies, and the Needfor Critical H istory ..............................................................................297 -

The Israeli Parliamentary Elections: a Splintering of the Arab Consensus?

INFO PACK The Israeli Parliamentary Elections: A Splintering of the Arab Consensus? Fatih Şemsettin Işık INFO PACK The Israeli Parliamentary Elections: A Splintering of the Arab Consensus? Fatih Şemsettin Işık The Israeli Parliamentary Elections: A Splintering of the Arab Consensus? © TRT WORLD RESEARCH CENTRE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PUBLISHER TRT WORLD RESEARCH CENTRE March 2021 WRITTEN BY Fatih Şemsettin Işık PHOTO CREDIT ANADOLU AGENCY TRT WORLD İSTANBUL AHMET ADNAN SAYGUN STREET NO:83 34347 ULUS, BEŞİKTAŞ İSTANBUL / TURKEY TRT WORLD LONDON 200 GRAYS INN ROAD, WC1X 8XZ LONDON / UNITED KINGDOM TRT WORLD WASHINGTON D.C. 1819 L STREET NW SUITE, 700 20036 WASHINGTON DC / UNITED STATES www.trtworld.com researchcentre.trtworld.com The opinions expressed in this Info Pack represent the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the TRT World Research Centre. 4 The Israeli Parliamentary Elections: A Splintering of the Arab Consensus? Introduction n March 3, 2020, the leader of the alliance, it is clear that the representation of Arab Joint List, an alliance of four Arab citizens of Israel has been undermined by the latest parties in Israel, proudly declared departure. Moreover, Ra’am’s exit also revealed the that they had won a huge achieve- fragility and vulnerability of this alliance, a reality that O ment in the parliamentary elections reflects internal disputes between the parties. by winning 15 seats in the Knesset, a record for Arab parties in Israel. Ayman Odeh, the leader of Hadash This info pack presents the latest situation concern- (The Democratic Front for Peace and Equality) party, ing Arab political parties in Israel ahead of the March urged “actual equality between Arabs and Jews and 23 elections. -

The Palestinians Between State Failure and Civil War

The Palestinians Between State Failure and Civil War Michael Eisenstadt Policy Focus #78 | December 2007 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2007 by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy Published in 2007 in the United States of America by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050, Washington, DC 20036. Design by Daniel Kohan, Sensical Design and Communication Front cover: Palestinian women cover their faces from the smell of garbage piled in the street in Gaza City, Octo- ber 23, 2006. Copyright AP Wide World Photos/Emilio Morenatti. About the Author Michael Eisenstadt is a senior fellow and director of the Military and Security Studies Program at The Washington Institute. Prior to joining the Institute in 1989, he worked as a civilian military analyst with the U.S. Army. An officer in the Army Reserve, he served on active duty in 2001–2002 at U.S. Central Command and on the Joint Staff during Operation Enduring Freedom and the planning for Operation Iraqi Freedom. He is coeditor (with Patrick Clawson) of the Institute paper Deterring the Ayatollahs: Complications in Applying Cold War Strategy to Iran. n n n The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. -

Integrating the Arab-Palestinian Minority in Israeli Society: Time for a Strategic Change Ephraim Lavie

Integrating the Arab-Palestinian Minority in Israeli Society: Time for a Strategic Change Ephraim Lavie Contributors: Meir Elran, Nadia Hilou, Eran Yashiv, Doron Matza, Keren Aviram, Hofni Gartner The Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Research Integrating the Arab-Palestinian Minority in Israeli Society: Time for a Strategic Change Ephraim Lavie Contributors: Meir Elran, Nadia Hilou, Eran Yashiv, Doron Matza, Keren Aviram, Hofni Gartner This book was written within the framework of the research program on the Arabs in Israel and was published thanks to the generous financial support of Bank Hapoalim and Joseph and Jeanette Neubauer of Philadelphia, Penn. Institute for National Security Studies The Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), incorporating the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies, was founded in 2006. The purpose of the Institute for National Security Studies is first, to conduct basic research that meets the highest academic standards on matters related to Israel’s national security as well as Middle East regional and international security affairs. Second, the Institute aims to contribute to the public debate and governmental deliberation of issues that are – or should be – at the top of Israel’s national security agenda. INSS seeks to address Israeli decision makers and policymakers, the defense establishment, public opinion makers, the academic community in Israel and abroad, and the general public. INSS publishes research that it deems worthy of public attention, while it maintains a strict policy of non-partisanship. The opinions expressed in this publication are the authors’ alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute, its trustees, boards, research staff, or the organizations and individuals that support its research. -

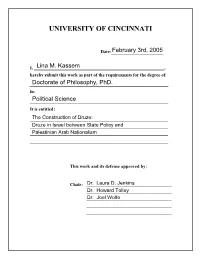

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The Construction of Druze Ethnicity: Druze in Israel between State Policy and Palestinian Arab Nationalism A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Political Science of the College of Arts and Sciences 2005 by Lina M. Kassem B.A. University of Cincinnati, 1991 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 1998 Committee Chair: Professor Laura Jenkins i ABSTRACT: Eric Hobsbawm argues that recently created nations in the Middle East, such as Israel or Jordan, must be novel. In most instances, these new nations and nationalism that goes along with them have been constructed through what Hobsbawm refers to as “invented traditions.” This thesis will build on Hobsbawm’s concept of “invented traditions,” as well as add one additional but essential national building tool especially in the Middle East, which is the military tradition. These traditions are used by the state of Israel to create a sense of shared identity. These “invented traditions” not only worked to cement together an Israeli Jewish sense of identity, they were also utilized to create a sub national identity for the Druze. The state of Israel, with the cooperation of the Druze elites, has attempted, with some success, to construct through its policies an ethnic identity for the Druze separate from their Arab identity.